Guerre d’indépendance américaine

La guerre d’indépendance américaine (19 avril 1775 – 3 septembre 1783), également connue sous le nom de guerre d’indépendance ou guerre d’indépendance américaine , a assuré l’indépendance des États-Unis d’Amérique vis-à- vis de la Grande-Bretagne . Les combats commencèrent le 19 avril 1775, suivis de la déclaration d’indépendance le 4 juillet 1776. Les patriotes américains furent soutenus par la France et l’Espagne , des conflits ayant lieu en Amérique du Nord , dans les Caraïbes et dans l’océan Atlantique .

| Guerre d’indépendance américaine | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre à partir de la gauche : infanterie continentale à Redoute 10, Yorktown ; Washington ralliant le centre brisé à Monmouth ; L’ USS Bonhomme Richard capturant le HMS Serapis |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| belligérants | ||||||||

Co-belligérants

Combattants

Amérindiens [4]

|

Beligérants du traité

|

|||||||

| Commandants et chefs | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Force | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Victimes et pertes | ||||||||

|

|

Établies par charte royale aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, les colonies américaines étaient largement autonomes dans les affaires intérieures et commercialement prospères, faisant du commerce avec la Grande-Bretagne et ses colonies des Caraïbes , ainsi qu’avec d’autres puissances européennes via leurs entrepôts des Caraïbes . Après la victoire britannique dans la guerre de Sept Ans en 1763, des tensions surgissent au sujet du commerce, de la politique coloniale dans les Territoires du Nord-Ouest et des mesures fiscales, notamment le Stamp Act et les Townshend Acts . L’opposition coloniale a conduit au massacre de Boston de 1770 et au Boston Tea Party de 1773 , avec le Parlementrépondre en imposant les actes dits intolérables .

Le 5 septembre 1774, le premier congrès continental rédige une pétition au roi et organise un boycott des marchandises britanniques. Malgré les tentatives pour parvenir à une solution pacifique, les combats ont commencé avec la bataille de Lexington le 19 avril 1775 et en juin , le Congrès a autorisé George Washington à créer une armée continentale , où John Adams a nommé Washington comme commandant en chef. Bien que la « politique de coercition » prônée par le ministère du Nord ait rencontré l’opposition d’une faction au sein du Parlement, les deux parties considéraient de plus en plus le conflit comme inévitable. La pétition du rameau d’olivierenvoyée par le Congrès à George III en juillet 1775 fut rejetée et en août le Parlement déclara les colonies en état de rébellion .

Suite à la perte de Boston en mars 1776, Sir William Howe , le nouveau commandant en chef britannique, lance la campagne de New York et du New Jersey . Il a capturé New York en novembre, avant que Washington ne remporte de petites mais importantes victoires à Trenton et Princeton , ce qui a restauré la confiance des Patriotes. À l’été 1777, Howe réussit à prendre Philadelphie , mais en octobre, une force distincte sous John Burgoyne fut forcée de se rendre à Saratoga.. Cette victoire a été cruciale pour convaincre des puissances comme la France et l’Espagne que les États-Unis indépendants étaient une entité viable. L’armée continentale a ensuite pris ses quartiers d’hiver à Valley Forge , où le général von Steuben l’a transformée en une unité de combat organisée.

La France a fourni aux États-Unis un soutien économique et militaire informel dès le début de la rébellion, et après Saratoga, les deux pays ont signé un accord commercial et un traité d’alliance en février 1778. En échange d’une garantie d’indépendance, le Congrès a rejoint la France dans sa guerre mondiale . avec la Grande-Bretagne et accepta de défendre les Antilles françaises . L’Espagne s’est également alliée à la France contre la Grande-Bretagne dans le traité d’Aranjuez (1779) , bien qu’elle ne se soit pas formellement alliée aux Américains. Néanmoins, l’accès aux ports de la Louisiane espagnole a permis aux Patriots d’importer des armes et des fournitures, tandis que la campagne de la côte espagnole du golfe a privé la Royal Navyde bases clés dans le sud.

Cela a sapé la stratégie de 1778 conçue par le remplaçant de Howe, Sir Henry Clinton , qui a mené la guerre dans le sud des États-Unis . Malgré quelques premiers succès, en septembre 1781, Cornwallis est assiégée par une force franco-américaine à Yorktown . Après l’ échec d’une tentative de réapprovisionnement de la garnison , Cornwallis se rend en octobre, et bien que les guerres britanniques avec la France et l’Espagne se poursuivent pendant encore deux ans, cela met fin aux combats en Amérique du Nord. En avril 1782, le ministère du Nord est remplacé par un nouveau gouvernement britanniquequi a accepté l’indépendance américaine et a commencé à négocier le traité de Paris, ratifié le 3 septembre 1783. La guerre s’est officiellement terminée le 3 septembre 1783 lorsque la Grande-Bretagne a accepté l’indépendance américaine dans le traité de Paris , tandis que les traités de Versailles ont résolu des conflits séparés avec la France et Espagne . [41]

Prélude à la révolution

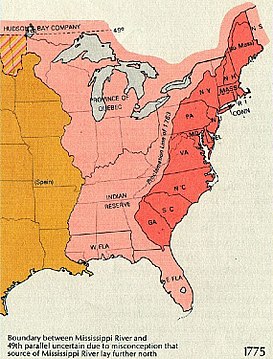

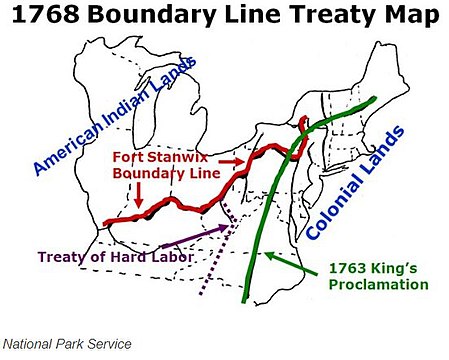

Ligne de proclamation de 1763 (ligne verte) plus cessions territoriales jusqu’en 1774

Ligne de proclamation de 1763 (ligne verte) plus cessions territoriales jusqu’en 1774

La guerre française et indienne , qui fait partie du conflit mondial plus large connu sous le nom de guerre de Sept Ans , s’est terminée par la paix de Paris de 1763 , qui a expulsé la France de ses possessions en Nouvelle-France . [42] L’acquisition de territoires au Canada atlantique et en Floride occidentale , habités en grande partie par des catholiques francophones ou hispanophones, conduit les autorités britanniques à consolider leur emprise en les peuplant de colons anglophones. Prévenir les conflits entre les colons et les tribus amérindiennes à l’ouest des Appalaches éviterait également le coût d’une occupation militaire coûteuse. [43]

La ligne de proclamation de 1763 a été conçue pour atteindre ces objectifs en recentrant l’expansion coloniale au nord en Nouvelle-Écosse et au sud en Floride, avec le fleuve Mississippi comme ligne de démarcation entre les possessions britanniques et espagnoles dans les Amériques. La colonisation au-delà des limites de 1763 a été strictement limitée, tandis que les revendications des colonies individuelles à l’ouest de cette ligne ont été annulées, notamment la Virginie et le Massachusetts qui ont soutenu que leurs frontières s’étendaient de l’ Atlantique au Pacifique . [43]

En fin de compte, le vaste échange de territoire a déstabilisé les alliances et les réseaux commerciaux existants entre les colons et les Amérindiens dans l’ouest, alors qu’il s’est avéré impossible d’empêcher l’empiétement au-delà de la ligne de proclamation. [44] À l’exception de la Virginie et d’autres « privés » de leurs droits sur les terres de l’Ouest, les législatures coloniales étaient généralement d’accord sur le principe des frontières mais n’étaient pas d’accord sur l’endroit où les fixer, tandis que de nombreux colons étaient mécontents des restrictions. Étant donné que l’application de la loi nécessitait des garnisons permanentes le long de la frontière, cela a conduit à des conflits de plus en plus amers pour savoir qui devait les payer. [45]

Fiscalité et législation

Le Boston Tea Party de 1773

Le Boston Tea Party de 1773

dans une impression sympathique du XIXe siècle.

Bien qu’administrées directement par la Couronne, agissant par l’intermédiaire d’un gouverneur local, les colonies étaient en grande partie gouvernées par des propriétaires nés dans le pays. Alors que les affaires extérieures étaient gérées par Londres , les milices coloniales étaient financées localement mais avec la fin de la menace française en 1763, les législateurs s’attendaient à moins de taxation, pas plus. Dans le même temps, l’énorme dette contractée par la guerre de Sept Ans et les demandes des contribuables britanniques de réduire les dépenses publiques signifiaient que le Parlement s’attendait à ce que les colonies financent leur propre défense. [45]

Le ministère de Grenville de 1763 à 1765 ordonna à la Royal Navy d’arrêter le commerce des marchandises de contrebande et de faire respecter les droits de douane perçus dans les ports américains. [45] Le plus important est le Molasses Act de 1733 ; systématiquement ignoré avant 1763, il a eu un impact économique important puisque 85% des exportations de rhum de la Nouvelle-Angleterre étaient fabriqués à partir de mélasse importée. Ces mesures ont été suivies par le Sugar Act et le Stamp Act , qui imposaient des taxes supplémentaires aux colonies pour payer la défense de la frontière occidentale. [46] En juillet 1765, les Whigs formèrent le premier ministère de Rockingham, qui a abrogé le Stamp Act et réduit la taxe sur la mélasse étrangère pour aider l’économie de la Nouvelle-Angleterre, mais a réaffirmé l’autorité parlementaire dans le Declaratory Act . [47]

Un douanier loyaliste

Un douanier loyaliste

goudronné et emplumé

par les Fils de la Liberté

Cependant, cela n’a pas fait grand-chose pour mettre fin au mécontentement; en 1768, une émeute a éclaté à Boston lorsque les autorités ont saisi le sloop Liberty , soupçonné de contrebande. [48] Les tensions se sont intensifiées en mars 1770 lorsque les troupes britanniques ont tiré sur des civils lanceurs de pierres, tuant cinq personnes dans ce qui est devenu connu sous le nom de Massacre de Boston . [49] Le Massacre a coïncidé avec l’abrogation partielle des Townshend Acts par le ministère du Nord basé sur les conservateurs , qui est arrivé au pouvoir en janvier 1770 et est resté en fonction jusqu’en 1781. North a insisté pour conserver le devoir sur le thé pour consacrer le droit du Parlement de taxer le colonies; le montant était mineur, mais ignorait le fait que c’était le principe même que les Américains trouvaient répréhensible.[50]

Les tensions s’exacerbèrent à la suite de la destruction d’un navire douanier lors de l’ affaire de Gaspé en juin 1772 , puis atteignirent leur paroxysme en 1773. Une crise bancaire conduisit au quasi-effondrement de la Compagnie des Indes orientales , qui dominait l’économie britannique ; pour la soutenir, le Parlement a adopté la loi sur le thé , lui conférant un monopole commercial dans les Treize Colonies . Étant donné que la plupart du thé américain était passé en contrebande par les Néerlandais, la loi s’est heurtée à l’opposition de ceux qui géraient le commerce illégal, tout en étant considérée comme une énième tentative d’imposer le principe de taxation par le Parlement. [51] En décembre 1773, un groupe appelé les Fils de la Libertédéguisés en indigènes mohawks ont jeté 342 caisses de thé dans le port de Boston, un événement connu plus tard sous le nom de Boston Tea Party . Le Parlement a répondu en adoptant les soi-disant actes intolérables , visant spécifiquement le Massachusetts, bien que de nombreux colons et membres de l’opposition whig les aient considérés comme une menace pour la liberté en général. Cela a conduit à une sympathie accrue pour la cause patriote localement, ainsi qu’au Parlement et dans la presse londonienne. [52]

Rompre avec la couronne britannique

Au cours du XVIIIe siècle, les chambres basses élues des législatures coloniales ont progressivement arraché le pouvoir à leurs gouverneurs royaux. [53] Dominées par de plus petits propriétaires terriens et marchands, ces assemblées ont maintenant établi des législatures provinciales ad hoc, diversement appelées congrès, conventions et conférences, remplaçant efficacement le contrôle royal. À l’exception de la Géorgie , douze colonies envoyèrent des représentants au premier congrès continental pour convenir d’une réponse unifiée à la crise. [54] De nombreux délégués craignaient qu’un boycott total n’entraîne une guerre et envoyèrent une pétition au roi appelant à l’abrogation des actes intolérables. [55]Cependant, après quelques débats, le 17 septembre 1774, le Congrès approuva les Massachusetts Suffolk Resolves et le 20 octobre passa la Continental Association ; basé sur un projet préparé par la Première Convention de Virginie en août, cela a institué des sanctions économiques contre la Grande-Bretagne. [56]

- Réponse coloniale

-

![Scene from the Second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry giving his speech, "Give me liberty or give me death!"]()

![Scene from the Second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry giving his speech, "Give me liberty or give me death!"]()

Patrick Henry , 2e Convention de Virginie

“Donnez-moi la liberté ou donnez-moi la mort!”

a été signalé dans toutes les colonies -

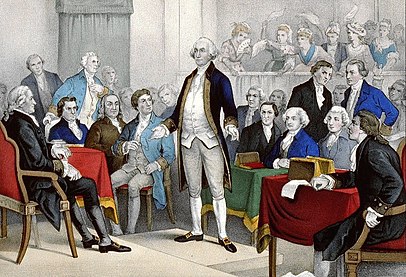

![Scene from the First Continental Congress, George Washington appointed as Commander-in-Chief for the new Continental Army besieging Boston.]()

![Scene from the First Continental Congress, George Washington appointed as Commander-in-Chief for the new Continental Army besieging Boston.]()

Juillet 1775, Independence Hall, Philadelphie

George Washington (debout, au centre)

est nommé commandant en chef du Congrès

Tout en niant son autorité sur les affaires intérieures américaines, une faction dirigée par James Duane et le futur loyaliste Joseph Galloway a insisté pour que le Congrès reconnaisse le droit du Parlement de réglementer le commerce colonial. [56] [v] S’attendant à des concessions de l’administration du Nord, le Congrès a autorisé les comités extralégaux et les conventions des législatures coloniales à imposer le boycott; cela a réussi à réduire les importations britanniques de 97% de 1774 à 1775. [57] Cependant, le 9 février, le Parlement a déclaré que le Massachusetts était en état de rébellion et a institué un blocus de la colonie. [58] En juillet, les Restraining Acts limitent le commerce colonial avec les Antilles britanniqueset la Grande – Bretagne et interdit aux navires de la Nouvelle – Angleterre de pêcher la morue à Terre – Neuve . L’augmentation de la tension a conduit à une ruée vers le contrôle des magasins de la milice, que chaque Assemblée était légalement tenue d’entretenir pour la défense. [59] Le 19 avril, une tentative britannique de sécuriser l’arsenal de Concord a abouti aux batailles de Lexington et de Concord qui ont commencé la guerre. [60]

Amérique du Nord britannique,

Amérique du Nord britannique,

concessions de 1777 après 1763 à la Grande-Bretagne

de la France (vert) et de l’Espagne (jaune)

Réactions politiques

Après la victoire des Patriotes à Concord, les modérés du Congrès dirigés par John Dickinson ont rédigé la pétition Olive Branch , proposant d’accepter l’autorité royale en échange de la médiation de George III dans le différend. [61] Cependant, puisqu’elle a été immédiatement suivie par la Déclaration des causes et de la nécessité de prendre les armes , le secrétaire colonial Dartmouth a considéré l’offre comme peu sincère ; il a refusé de présenter la pétition au roi, qui a donc été rejetée début septembre. [62] Bien que constitutionnellement correct, puisque George ne pouvait pas s’opposer à son propre gouvernement, il a déçu les Américains qui espéraient qu’il servirait de médiateur dans le différend, tandis que l’hostilité de sa langue ennuyait mêmeMembres loyalistes du Congrès. [61] Combiné avec la proclamation de rébellion , publiée le 23 août en réponse à la bataille de Bunker Hill, il a mis fin aux espoirs d’un règlement pacifique. [63]

Soutenu par les Whigs , le Parlement a d’abord rejeté l’imposition de mesures coercitives par 170 voix, craignant qu’une politique agressive ne pousse simplement les Américains vers l’indépendance. [64] Cependant, à la fin de 1774, l’effondrement de l’autorité britannique signifiait que North et George III étaient convaincus que la guerre était inévitable. [65] Après Boston, Gage a arrêté des opérations et a attendu des renforts; le Parlement irlandais a approuvé le recrutement de nouveaux régiments, tout en permettant aux catholiques de s’enrôler pour la première fois. [66] La Grande-Bretagne a également signé une série de traités avec des États allemands pour fournir des troupes supplémentaires . [67]En un an, il avait une armée de plus de 32 000 hommes en Amérique, la plus grande jamais envoyée hors d’Europe à l’époque. [68]

Le Comité des Cinq pour la Déclaration

Le Comité des Cinq pour la Déclaration

présentant de gauche à droite : Adams (président), Sherman ,

Livingston , Jefferson (auteur principal), Franklin

L’emploi de soldats allemands contre des personnes considérées comme des citoyens britanniques a été opposé par de nombreux parlementaires, ainsi que par les assemblées coloniales; combiné au manque d’activité de Gage, il a permis aux Patriotes de prendre le contrôle des législatures. [69] Le soutien à l’indépendance a été stimulé par la brochure Common Sense de Thomas Paine , qui a plaidé pour l’autonomie américaine, qui a été largement réimprimée. [70] Pour rédiger la Déclaration d’indépendance , le Congrès a nommé le Comité des Cinq , composé de Thomas Jefferson , John Adams , Benjamin Franklin , Roger Sherman etRobert Livingston . [71] Identifiant les habitants des Treize Colonies comme “un seul peuple”, il dissout simultanément les liens politiques avec la Grande-Bretagne, tout en incluant une longue liste de violations présumées des “droits anglais” commises par George III. [72]

Le 2 juillet, le Congrès a voté pour l’indépendance et a publié la déclaration du 4 juillet [73] que Washington a lue à ses troupes à New York le 9 juillet. [74] À ce stade, la Révolution a cessé d’être un différend interne sur le commerce. et fiscales et est devenu une guerre civile, puisque chaque État représenté au Congrès était engagé dans une lutte avec la Grande-Bretagne, mais aussi divisé entre Patriotes et Loyalistes. [75] Les patriotes ont généralement soutenu l’indépendance de la Grande-Bretagne et une nouvelle union nationale au Congrès, tandis que les loyalistes sont restés fidèles à la domination britannique. Les estimations des nombres varient, une suggestion étant que la population dans son ensemble était répartie également entre les patriotes engagés, les loyalistes engagés et ceux qui étaient indifférents. [76]D’autres calculent le déversement comme 40% patriote, 40% neutre, 20% loyaliste, mais avec des variations régionales considérables. [77]

Au début de la guerre, le Congrès s’est rendu compte que vaincre la Grande-Bretagne nécessitait des alliances étrangères et la collecte de renseignements. Le Comité de correspondance secrète a été formé dans “le seul but de correspondre avec nos amis en Grande-Bretagne et dans d’autres parties du monde”. De 1775 à 1776, il a partagé des informations et construit des alliances par correspondance secrète, ainsi qu’employant des agents secrets en Europe pour recueillir des renseignements, mener des opérations d’infiltration, analyser des publications étrangères et lancer des campagnes de propagande patriote. [78] Paine a servi de secrétaire, tandis que Benjamin Franklin et Silas Deane , envoyés en France pour recruter des ingénieurs militaires, [79] ont joué un rôle déterminant dans la sécurisation de l’aide française à Paris.[80]

La guerre éclate

La guerre se composait de deux principaux théâtres de campagne dans les treize États et d’un théâtre plus petit mais stratégiquement important à l’ ouest des Appalaches . Les combats ont commencé dans le théâtre du Nord et ont été les plus violents de 1775 à 1778. Les Patriotes ont remporté plusieurs victoires stratégiques dans le Sud et après avoir vaincu une armée britannique à Saratoga en octobre 1777, les Français sont officiellement entrés dans la guerre en tant qu’alliés américains. [81]

En 1778, Washington empêche l’armée britannique de sortir de New York, tandis que la milice sous George Rogers Clark appuyée par les colons francophones et leurs alliés indiens conquiert l’Ouest du Québec , qui devient le Territoire du Nord-Ouest . La guerre dans le nord étant dans l’impasse, les Britanniques lancèrent en 1779 leur stratégie du sud , qui visait à mobiliser le soutien loyaliste dans la région et à réoccuper le territoire contrôlé par les patriotes au nord de la baie de Chesapeake . La campagne a d’abord été un succès, la capture britannique de Charleston étant un revers majeur pour les patriotes du sud; cependant, une force franco-américaine a encerclé une armée britannique à Yorktownet leur reddition en octobre 1781 a effectivement mis fin aux combats en Amérique du Nord. [76]

Premiers engagements

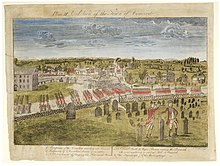

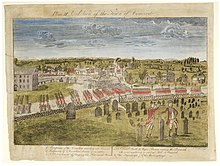

Les troupes britanniques quittent Boston, avant la bataille de Lexington et Concord , le 19 avril 1775

Les troupes britanniques quittent Boston, avant la bataille de Lexington et Concord , le 19 avril 1775

Le 14 avril 1775, Sir Thomas Gage , commandant en chef de l’Amérique du Nord depuis 1763 et également gouverneur du Massachusetts à partir de 1774, reçoit l’ordre d’agir contre les Patriotes. Il décida de détruire les munitions de la milice stockées à Concord, Massachusetts , et de capturer John Hancock et Samuel Adams , qui étaient considérés comme les principaux instigateurs de la rébellion. L’opération devait débuter vers minuit le 19 avril, dans l’espoir de la terminer avant que les Patriotes ne puissent réagir. [82] [83] Cependant, Paul Revere a appris le plan et a informé le capitaine Parker, commandant de la milice de Concord, qui s’est préparé à résister à la tentative de saisie. [84] La première action de la guerre était communément appelée le coup de feu entendu dans le monde entier impliquait une brève escarmouche à Lexington, suivie d’une bataille à grande échelle pendant les batailles de Lexington et de Concord . Les troupes britanniques ont subi environ 300 pertes avant de se retirer à Boston, qui a ensuite été assiégée par la milice. [85]

En mai, 4 500 renforts britanniques sont arrivés sous les ordres des généraux William Howe , John Burgoyne et Sir Henry Clinton . [86] Le 17 juin, ils s’emparèrent de la péninsule de Charlestown lors de la bataille de Bunker Hill , un assaut frontal au cours duquel ils subirent plus de 1 000 pertes. [87] Consterné par l’attaque coûteuse qui les avait peu gagnés, [88] Gage fit appel à Londres pour qu’une plus grande armée réprime la révolte, [89] mais fut plutôt remplacé comme commandant par Howe. [87]

Le 14 juin 1775, le Congrès prit le contrôle des forces patriotes à l’extérieur de Boston et le chef du Congrès John Adams nomma George Washington commandant en chef de la nouvelle armée continentale . [90] Washington commandait auparavant des régiments de la milice de Virginie pendant la guerre française et indienne , [91] et le 16 juin, John Hancock le proclama officiellement « général et commandant en chef de l’armée des colonies unies ». [92] Il a pris le commandement le 3 juillet, préférant fortifier Dorchester Heights à l’extérieur de Boston plutôt que de l’attaquer. [93] Début mars 1776, le colonel Henry Knox arrive avecartillerie lourde acquise lors de la prise de Fort Ticonderoga . [94] Sous le couvert de l’obscurité, le 5 mars, Washington les plaça sur Dorchester Heights, [95] d’où ils pouvaient tirer sur la ville et les navires britanniques dans le port de Boston . Craignant un autre Bunker Hill, Howe a évacué la ville le 17 mars sans autre perte et a navigué vers Halifax, en Nouvelle-Écosse , tandis que Washington s’est déplacé vers le sud jusqu’à New York . [96]

Les réguliers britanniques et la milice provinciale repoussent une attaque américaine contre Québec , décembre 1775

Les réguliers britanniques et la milice provinciale repoussent une attaque américaine contre Québec , décembre 1775

À partir d’août 1775, des corsaires américains ont attaqué des villes de la Nouvelle-Écosse, notamment Saint John , Charlottetown et Yarmouth . En 1776, John Paul Jones et Jonathan Eddy attaquèrent respectivement Canso et Fort Cumberland . Les fonctionnaires britanniques au Québec ont commencé à négocier avec les Iroquois pour leur soutien, [97] tandis que les envoyés américains les ont exhortés à rester neutres. [98] Conscient des tendances amérindiennes envers les Britanniques et craignant une attaque anglo-indienne du Canada, le Congrès autorisa une deuxième invasion en avril 1775. [99]Après la défaite à la bataille de Québec le 31 décembre [100] , les Américains ont maintenu un blocus lâche de la ville jusqu’à ce qu’ils se retirent le 6 mai 1776. [101] Une deuxième défaite à Trois-Rivières le 8 juin a mis fin aux opérations à Québec. [102]

La poursuite britannique a d’abord été bloquée par des navires de la marine américaine sur le lac Champlain jusqu’à ce que la victoire à l’île Valcour le 11 octobre oblige les Américains à se retirer à Fort Ticonderoga , tandis qu’en décembre, un soulèvement en Nouvelle-Écosse parrainé par le Massachusetts a été vaincu à Fort Cumberland . [103] Ces échecs ont eu un impact sur le soutien du public à la cause patriote, [104] et les politiques anti-loyalistes agressives dans les colonies de la Nouvelle-Angleterre ont aliéné les Canadiens. [105]

En Virginie , une tentative du gouverneur Lord Dunmore de s’emparer des magasins de la milice le 20 avril 1775 a entraîné une augmentation de la tension, bien que le conflit ait été évité pour le moment. [106] Cela a changé après la publication de la proclamation de Dunmore le 7 novembre 1775, promettant la liberté à tous les esclaves qui fuyaient leurs maîtres patriotes et acceptaient de se battre pour la Couronne. [107] Les forces britanniques sont vaincues à Great Bridge le 9 décembre et se réfugient sur des navires britanniques ancrés près du port de Norfolk. Lorsque la Troisième Convention de Virginie a refusé de dissoudre sa milice ou d’accepter la loi martiale, Dunmore a ordonné laIncendie de Norfolk le 1er janvier 1776. [108]

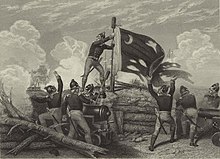

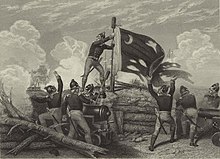

sergent. Jasper hissant le drapeau du fort,

sergent. Jasper hissant le drapeau du fort,

bataille de l’île de Sullivan , juin 1776

Le siège de Savage’s Old Fields a commencé le 19 novembre en Caroline du Sud entre les milices loyalistes et patriotes, [109] et les loyalistes ont ensuite été chassés de la colonie lors de la campagne de neige . [110] Les loyalistes ont été recrutés en Caroline du Nord pour réaffirmer la domination britannique dans le Sud, mais ils ont été vaincus de manière décisive lors de la bataille de Moore’s Creek Bridge . [111] Une expédition britannique envoyée pour reconquérir la Caroline du Sud a lancé une attaque sur Charleston lors de la bataille de Sullivan’s Island le 28 juin 1776, [112]mais il échoua et laissa le Sud sous le contrôle des Patriotes jusqu’en 1780. [113]

Une pénurie de poudre à canon a conduit le Congrès à autoriser une expédition navale contre les Bahamas pour sécuriser les munitions qui y sont stockées. [114] Le 3 mars 1776, un escadron américain sous le commandement d’Esek Hopkins débarqua à l’extrémité est de Nassau et rencontra une résistance minimale à Fort Montagu . Les troupes de Hopkins marchent alors sur Fort Nassau . Hopkins avait promis au gouverneur Montfort Browneet les habitants civils de la région que leurs vies et leurs biens ne seraient pas en danger s’ils n’opposaient aucune résistance, ce à quoi ils se sont conformés. Hopkins a capturé d’importants stocks de poudre et d’autres munitions qui étaient si importants qu’il a dû impressionner un navire supplémentaire dans le port pour transporter les fournitures à la maison, lorsqu’il est parti le 17 mars. [115] Un mois plus tard, après une brève escarmouche avec le HMS Glasgow , ils retournèrent à New London, Connecticut , la base des opérations navales américaines pendant la Révolution. [116]

Contre-offensive britannique à New York

Après s’être regroupé à Halifax, en Nouvelle-Écosse , William Howe était déterminé à mener le combat contre les Américains. Il a navigué pour New York en juin 1776 et a commencé à débarquer des troupes sur Staten Island près de l’entrée du port de New York le 2 juillet. Les Américains ont rejeté la tentative informelle de Howe de négocier la paix le 30 juillet ; [118] Washington savait qu’une attaque contre la ville était imminente et s’est rendu compte qu’il avait besoin d’informations préalables pour faire face aux troupes régulières britanniques disciplinées. Le 12 août 1776, le patriote Thomas Knowlton reçut l’ordre de former un groupe d’élite pour des missions de reconnaissance et secrètes. Les Rangers de Knowlton , qui comprenait Nathan Hale, est devenu la première unité de renseignement de l’armée. [119] [w] Lorsque Washington a été chassé de Long Island, il s’est vite rendu compte qu’il aurait besoin de plus que de la puissance militaire et d’espions amateurs pour vaincre les Britanniques. Il s’est engagé à professionnaliser le renseignement militaire et, avec l’aide de Benjamin Tallmadge , ils ont lancé le réseau d’ espionnage Culper composé de six hommes . [122] [x] Les efforts de Washington et du Culper Spy Ring ont considérablement augmenté l’allocation et le déploiement efficaces des régiments continentaux sur le terrain. [122] Au cours de la guerre, Washington a dépensé plus de 10 % de ses fonds militaires totaux dans des opérations de renseignement. [123]

Une compagnie américaine en ligne, bataille de Long Island , août 1776

Une compagnie américaine en ligne, bataille de Long Island , août 1776

Washington a divisé son armée en positions sur l’île de Manhattan et de l’autre côté de l’ East River dans l’ouest de Long Island . [124] Le 27 août à la bataille de Long Island, Howe a débordé Washington et l’a forcé à revenir à Brooklyn Heights , mais il n’a pas tenté d’encercler les forces de Washington. [125] Dans la nuit du 28 août, le général Henry Knox a bombardé les Britanniques. Sachant qu’ils étaient confrontés à des obstacles écrasants, Washington ordonna la réunion d’un conseil de guerre le 29 août ; tous ont accepté de se retirer à Manhattan. Washington a rapidement rassemblé ses troupes et les a transportées de l’autre côté de l’East River jusqu’à Manhattan sur des bateaux de fret à fond plat.sans aucune perte en hommes ou en munitions, laissant les régiments du général Thomas Mifflin comme arrière-garde. [126]

Le général Howe a officiellement rencontré une délégation du Congrès lors de la conférence de paix de Staten Island en septembre , mais celle-ci n’a pas réussi à conclure la paix car les délégués britanniques n’avaient que le pouvoir d’offrir des pardons et ne pouvaient pas reconnaître l’indépendance. [127] Le 15 septembre, Howe a pris le contrôle de New York lorsque les Britanniques ont débarqué à Kip’s Bay et ont engagé sans succès les Américains à la bataille de Harlem Heights le lendemain. [128] Le 18 octobre, Howe n’a pas réussi à encercler les Américains lors de la bataille de Pell’s Point , et les Américains se sont retirés. Howe a refusé de se rapprocher de l’armée de Washington le 28 octobre lors de la bataille de White Plains, et à la place attaqua une colline qui n’avait aucune valeur stratégique. [129]

Les Britanniques ont forcé le rétrécissement de la rivière Hudson pour isoler Fort Washington , novembre 1776

Les Britanniques ont forcé le rétrécissement de la rivière Hudson pour isoler Fort Washington , novembre 1776

La retraite de Washington a isolé ses forces restantes et les Britanniques ont capturé Fort Washington le 16 novembre. La victoire britannique là-bas équivalait à la défaite la plus désastreuse de Washington avec la perte de 3 000 prisonniers. [130] Les régiments américains restants sur Long Island se sont repliés quatre jours plus tard. [131] Le général Sir Henry Clinton voulait poursuivre l’armée désorganisée de Washington, mais il devait d’abord engager 6 000 soldats pour capturer Newport, Rhode Island afin de sécuriser le port loyaliste. [132] [y] Le général Charles Cornwallis a poursuivi Washington, mais Howe lui a ordonné de s’arrêter, laissant Washington sans encombre. [134]

Les perspectives étaient sombres pour la cause américaine: l’armée réduite était tombée à moins de 5 000 hommes et serait encore réduite lorsque les enrôlements expireraient à la fin de l’année. [135] Le soutien populaire a vacillé, le moral a baissé et le Congrès a abandonné Philadelphie et a déménagé à Baltimore . [136] L’activité loyaliste a bondi à la suite de la défaite américaine, en particulier dans l’État de New York . [137]

À Londres, la nouvelle de la campagne victorieuse de Long Island a été bien accueillie avec des festivités organisées dans la capitale. Le soutien public a atteint un sommet, [138] et le roi George III a décerné l’ Ordre du Bain à Howe. [139] Les lacunes stratégiques parmi les forces patriotes étaient évidentes : Washington a divisé une armée numériquement plus faible face à une armée plus forte, son état-major inexpérimenté a mal interprété la situation militaire et les troupes américaines ont fui face aux tirs ennemis. Les succès ont conduit à des prédictions selon lesquelles les Britanniques pourraient gagner d’ici un an. [140] Entre-temps, les Britanniques ont établi des quartiers d’hiver dans la région de New York et ont prévu une nouvelle campagne au printemps suivant. [141]

Résurgence patriote

Peinture emblématique de 1851 représentant Washington traversant le Delaware

Peinture emblématique de 1851 représentant Washington traversant le Delaware

Deux semaines après le retrait du Congrès dans le Maryland, Washington traversa le fleuve Delaware à environ 30 milles en amont de Philadelphie dans la nuit du 25 au 26 décembre 1776. Pendant ce temps, les Hessois étaient impliqués dans de nombreux affrontements avec de petites bandes de patriotes et étaient souvent réveillés par de fausses alarmes. la nuit dans les semaines précédant la véritable bataille de Trenton . À Noël, ils étaient fatigués et fatigués, tandis qu’une forte tempête de neige conduisait leur commandant, le colonel Johann Rall , à supposer qu’aucune attaque de quelque conséquence que ce soit ne se produirait. [142] À l’aube du 26, les patriotes américains ont surpris et submergé Rall et ses troupes, qui ont perdu plus de 20 tués, dont Rall, [143]tandis que 900 prisonniers, des canons allemands et beaucoup de ravitaillement ont été capturés. [144]

La bataille de Trenton a restauré le moral de l’armée américaine, a revigoré la cause des patriotes [145] et a dissipé leur peur de ce qu’ils considéraient comme des “mercenaires” hessois. [146] Une tentative britannique de reprendre Trenton a été repoussée à Assunpink Creek le 2 janvier; [147] pendant la nuit, Washington a déjoué Cornwallis, puis a vaincu son arrière-garde dans la Bataille de Princeton le jour suivant. Les deux victoires contribuèrent à convaincre les Français que les Américains étaient de dignes alliés militaires. [148]

Après son succès à Princeton, Washington entra en quartiers d’hiver à Morristown, New Jersey , où il resta jusqu’en mai. [149] et il a reçu la direction congressionnelle pour inoculer toutes les troupes de patriote contre la variole . [150] [z] À l’exception d’une escarmouche mineure entre les deux armées qui a continué jusqu’en mars, [152] Howe n’a fait aucune tentative d’attaquer les Américains. [153]

La stratégie nordique britannique échoue

Manœuvre de la campagne de Saratoga

Manœuvre de la campagne de Saratoga

et (en médaillon) les batailles de Saratoga de septembre à octobre 1777

La campagne de 1776 a démontré que regagner la Nouvelle-Angleterre serait une affaire prolongée, ce qui a conduit à un changement de stratégie britannique. Cela impliquait d’isoler le nord du reste du pays en prenant le contrôle de la rivière Hudson , leur permettant de se concentrer sur le sud où le soutien loyaliste était considéré comme substantiel. [154] En décembre 1776, Howe écrivit au secrétaire colonial Lord Germain , proposant une offensive limitée contre Philadelphie, tandis qu’une deuxième force descendait l’Hudson depuis le Canada. [155] Germain le reçut le 23 février 1777, suivi quelques jours plus tard d’un mémorandum de Burgoyne, alors en permission à Londres. [156]

Burgoyne a fourni plusieurs alternatives, qui lui ont toutes donné la responsabilité de l’offensive, Howe restant sur la défensive. L’option choisie l’obligeait à diriger la force principale au sud de Montréal dans la vallée de l’Hudson, tandis qu’un détachement sous Barry St. Leger se déplaçait à l’est du lac Ontario. Les deux se rencontreraient à Albany , laissant Howe décider de les rejoindre ou non. [156] Raisonnable en principe, cela ne tenait pas compte des difficultés logistiques impliquées et Burgoyne supposait à tort que Howe resterait sur la défensive; Le fait que Germain n’ait pas précisé cela signifiait qu’il avait plutôt choisi d’attaquer Philadelphie . [157]

Burgoyne partit le 14 juin 1777, avec une force mixte de réguliers britanniques, de soldats allemands professionnels et de miliciens canadiens, et s’empara de Fort Ticonderoga le 5 juillet. Alors que le général Horatio Gates se retirait, ses troupes bloquaient des routes, détruisaient des ponts, endiguaient des ruisseaux et dépouillé le domaine de la nourriture. [158] Cela a ralenti les progrès de Burgoyne et l’a forcé à envoyer de grandes expéditions de recherche de nourriture; sur l’un d’eux, plus de 700 soldats britanniques ont été capturés à la bataille de Bennington le 16 août. [159] St Leger s’est déplacé vers l’est et a assiégé le fort Stanwix ; malgré la défaite d’une force de secours américaine à la bataille d’Oriskanyle 6 août, il a été abandonné par ses alliés indiens et s’est retiré à Québec le 22 août. [160] Désormais isolé et en infériorité numérique par Gates, Burgoyne a continué sur Albany plutôt que de se retirer à Fort Ticonderoga, atteignant Saratoga le 13 septembre. soutien tout en construisant des défenses autour de la ville. [161]

Reddition du général Burgoyne aux batailles de Saratoga par John Trumbull , 1821

Reddition du général Burgoyne aux batailles de Saratoga par John Trumbull , 1821

Le général britannique John Burgoyne (g.)

au général Horatio Gates , octobre 1777

Le moral de ses troupes a rapidement décliné et une tentative infructueuse de franchir Gates lors de la bataille de Freeman Farms le 19 septembre a fait 600 victimes britanniques. [162] Quand Clinton a conseillé qu’il ne pouvait pas les atteindre, les subalternes de Burgoyne ont conseillé la retraite; une reconnaissance en force le 7 octobre est repoussée par Gates à la bataille de Bemis Heights , les forçant à retourner à Saratoga avec de lourdes pertes. Le 11 octobre, tout espoir d’évasion avait disparu; des pluies persistantes ont réduit le camp à un “enfer sordide” de boue et de bétail affamé, les approvisionnements étaient dangereusement bas et de nombreux blessés à l’agonie. [163] Burgoyne a capitulé le 17 octobre ; environ 6 222 soldats, dont les forces allemandes commandées parLe général Riedesel , rendit leurs armes avant d’être emmenées à Boston, où elles devaient être transportées en Angleterre. [164]

Après avoir obtenu des approvisionnements supplémentaires, Howe a fait une autre tentative sur Philadelphie en débarquant ses troupes dans la baie de Chesapeake le 24 août. 11, puis lui permettant de se retirer en bon ordre. [166] Après avoir dispersé un détachement américain à Paoli le 20 septembre, Cornwallis a occupé Philadelphie le 26 septembre, avec la force principale de 9 000 sous Howe basée juste au nord à Germantown . [167] Washington les a attaqués le 4 octobre, mais a été repoussé. [168]

Pour empêcher les forces de Howe à Philadelphie d’être ravitaillées par voie maritime, les Patriotes ont érigé Fort Mifflin et Fort Mercer à proximité respectivement sur les rives est et ouest du Delaware, et ont placé des obstacles dans la rivière au sud de la ville. Celle-ci était soutenue par une petite flottille de navires de la Marine continentale sur le Delaware, complétée par la Marine de l’État de Pennsylvanie , commandée par John Hazelwood . Une tentative de la Royal Navy de prendre les forts lors de la bataille de Red Bank du 20 au 22 octobre a échoué; [169] [170]une deuxième attaque a capturé Fort Mifflin le 16 novembre, tandis que Fort Mercer a été abandonné deux jours plus tard lorsque Cornwallis a percé les murs. [171] Ses lignes d’approvisionnement sécurisées, Howe tenta de tenter Washington de livrer bataille, mais après des escarmouches peu concluantes lors de la bataille de White Marsh du 5 au 8 décembre, il se retira à Philadelphie pour l’hiver. [172]

Le général von Steuben

Le général von Steuben

entraîne “l’infanterie modèle” à

Valley Forge en décembre 1777

Le 19 décembre, les Américains emboîtent le pas et entrent en quartiers d’hiver à Valley Forge ; tandis que les adversaires nationaux de Washington opposaient son manque de succès sur le champ de bataille à la victoire de Gates à Saratoga, [173] des observateurs étrangers tels que Frédéric le Grand étaient également impressionnés par Germantown, qui faisait preuve de résilience et de détermination. [174] Au cours de l’hiver, les mauvaises conditions, les problèmes d’approvisionnement et le moral bas ont entraîné la mort de 2 000 personnes, et 3 000 autres inaptes au travail en raison du manque de chaussures. [175] Cependant, le baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben en profite pour présenter l’armée prussiennetactiques d’exercice et d’infanterie à l’ensemble de l’armée continentale; il l’a fait en formant des «compagnies modèles» dans chaque régiment, qui ont ensuite instruit leurs unités d’origine. [176] Bien que Valley Forge ne soit qu’à vingt miles de là, Howe n’a fait aucun effort pour attaquer leur camp, une action qui, selon certains critiques, aurait pu mettre fin à la guerre. [177]

Intervention étrangère

Charles, comte de Vergennes

Charles, comte de Vergennes

Le ministre français des Affaires étrangères a négocié

les traités franco-américains en février 1778

Comme ses prédécesseurs, le ministre français des Affaires étrangères Vergennes considérait la paix de 1763 comme une humiliation nationale* et considérait la guerre comme une occasion d’affaiblir la Grande-Bretagne. Il a d’abord évité un conflit ouvert, mais a permis aux navires américains d’embarquer des cargaisons dans les ports français, une violation technique de la neutralité. [178] Bien que l’opinion publique ait favorisé la cause américaine, le ministre des Finances Turgot a soutenu qu’ils n’avaient pas besoin de l’aide française pour gagner l’indépendance et que la guerre était trop chère. Au lieu de cela, Vergennes a persuadé Louis XVI de financer secrètement une société écran du gouvernement pour acheter des munitions pour les Patriotes, transportées dans des navires néerlandais neutres et importées via Saint-Eustache dans les Caraïbes.[179]

De nombreux Américains se sont opposés à une alliance française, craignant «d’échanger une tyrannie contre une autre», mais cela a changé après une série de revers militaires au début de 1776. Comme la France n’avait rien à gagner des colonies se réconciliant avec la Grande-Bretagne, le Congrès avait trois choix; faire la paix aux conditions britanniques, continuer la lutte par eux-mêmes ou proclamer l’indépendance, garantie par la France. Bien que la déclaration d’indépendance de juillet 1776 ait reçu un large soutien public, Adams était parmi ceux qui hésitaient à payer le prix d’une alliance avec la France, et plus de 20% des membres du Congrès ont voté contre. [180] Le Congrès a accepté le traité avec réticence et, à mesure que la guerre évoluait en leur faveur, il s’en est de plus en plus désintéressé. [181]

Silas Deane a été envoyé à Paris pour entamer des négociations avec Vergennes, dont les principaux objectifs étaient de remplacer la Grande-Bretagne en tant que principal partenaire commercial et militaire des États-Unis tout en sécurisant les Antilles françaises de l’expansion américaine. [182] Ces îles étaient extrêmement précieuses; en 1772, la valeur du sucre et du café produits par Saint-Domingue dépassait à elle seule celle de toutes les exportations américaines réunies. [183]Les pourparlers progressèrent lentement jusqu’en octobre 1777, lorsque la défaite britannique à Saratoga et leur apparente volonté de négocier la paix convainquirent Vergennes que seule une alliance permanente pourrait empêcher le «désastre» du rapprochement anglo-américain. Les assurances du soutien officiel de la France ont permis au Congrès de rejeter la Commission de paix de Carlisle et d’insister sur rien de moins qu’une indépendance complète. [184]

Le 6 février 1778, la France et les États-Unis signent le traité d’amitié et de commerce réglementant les échanges entre les deux pays, suivi d’une alliance militaire défensive contre la Grande-Bretagne, le traité d’alliance . En échange des garanties françaises d’indépendance américaine, le Congrès s’est engagé à défendre leurs intérêts aux Antilles, tandis que les deux parties ont convenu de ne pas faire de paix séparée; un conflit sur ces dispositions conduirait à la quasi-guerre de 1798 à 1800 . [181] Charles III d’Espagne a été invité à se joindre aux mêmes conditions mais a refusé, en grande partie en raison de préoccupations concernant l’impact de la Révolution sur les colonies espagnoles des Amériques. L’Espagne s’était plainte à plusieurs reprises de l’empiètement des colons américains surLouisiane , un problème qui ne pouvait que s’aggraver une fois que les États-Unis avaient remplacé la Grande-Bretagne. [185]

Bien que l’Espagne ait finalement apporté d’importantes contributions au succès américain, dans le traité d’Aranjuez (1779) , Charles n’a accepté que de soutenir la guerre de la France avec la Grande-Bretagne en dehors de l’Amérique, en échange d’une aide pour récupérer Gibraltar , Minorque et la Floride espagnole . [186] Les termes étaient confidentiels car plusieurs étaient en conflit avec les objectifs américains; par exemple, les Français revendiquaient le contrôle exclusif de la pêche à la morue de Terre-Neuve, un droit non négociable pour des colonies comme le Massachusetts. [187] Un impact moins bien connu de cet accord était la méfiance persistante des Américains à l’égard des « enchevêtrements étrangers » ; les États-Unis ne signeraient pas un autre traité avant l’ OTANaccord en 1949. [181] C’était parce que les États-Unis avaient accepté de ne pas faire la paix sans la France, tandis qu’Aranjuez engageait la France à continuer à se battre jusqu’à ce que l’Espagne récupère Gibraltar, ce qui en faisait une condition de l’indépendance américaine à l’insu du Congrès. [188]

Bataille de Flamborough Head ; Les navires de guerre américains dans les eaux européennes avaient accès aux ports néerlandais, français et espagnols

Bataille de Flamborough Head ; Les navires de guerre américains dans les eaux européennes avaient accès aux ports néerlandais, français et espagnols

Pour encourager la participation française à la lutte pour l’indépendance, le représentant américain à Paris, Silas Deane promet des postes de promotion et de commandement à tout officier français qui rejoint l’armée continentale. Bien que beaucoup se soient avérés incompétents, une exception exceptionnelle était Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette , que le Congrès via le doyen nomma général de division, [189] [190] le 31 juillet 1777. [191]

Lorsque la guerre a commencé, la Grande-Bretagne a tenté d’emprunter la Brigade écossaise basée aux Pays-Bas pour servir en Amérique, mais le sentiment pro-patriote a conduit les États généraux à refuser. [192] Bien que la République ne soit plus une puissance majeure, avant 1774, elle dominait encore le commerce de transport européen et les marchands hollandais réalisaient de gros bénéfices en expédiant des munitions fournies par la France aux Patriotes. Cela a pris fin lorsque la Grande-Bretagne a déclaré la guerre en décembre 1780, un conflit qui s’est avéré désastreux pour l’économie néerlandaise. [193] Les Néerlandais ont également été exclus de la Première Ligue de neutralité armée, formé par la Russie, la Suède et le Danemark en mars 1780 pour protéger la navigation neutre contre l’arrêt et la recherche de contrebande par la Grande-Bretagne et la France. [194]

Le gouvernement britannique n’a pas tenu compte de la force de la marine marchande américaine et du soutien des pays européens, ce qui a permis aux colonies d’importer des munitions et de continuer à commercer avec une relative impunité. Bien que consciente de cela, l’administration du Nord a retardé la mise sur pied de guerre de la Royal Navy pour des raisons de coût; cela a empêché l’institution d’un blocus efficace et les a limités à des protestations diplomatiques inefficaces. [195] La politique britannique traditionnelle était d’employer des alliés terrestres européens pour détourner l’opposition, un rôle rempli par la Prusse dans la guerre de Sept Ans ; en 1778, ils étaient diplomatiquement isolés et faisaient face à la guerre sur plusieurs fronts. [196]

Pendant ce temps, George III avait renoncé à soumettre l’Amérique alors que la Grande-Bretagne avait une guerre européenne à mener. [197] Il n’a pas fait bon accueil à la guerre avec la France, mais il a cru les victoires britanniques sur la France dans la guerre de Sept Ans comme une raison de croire en victoire finale sur la France. [198] La Grande-Bretagne n’a pas pu trouver d’allié puissant parmi les grandes puissances pour engager la France sur le continent européen. [199] La Grande-Bretagne a changé par la suite son foyer dans le théâtre des Caraïbes, [200] et a détourné des ressources militaires importantes loin de l’Amérique. [201]

- Collègue de Vergennes “Pour son honneur, la France devait saisir cette opportunité de se relever de sa dégradation……

“Si elle le négligeait, si la peur l’emportait sur le devoir, elle ajouterait l’avilissement à l’humiliation, et deviendrait un objet de mépris pour son propre siècle et pour tous les peuples futurs”. [202]

Impasse dans le Nord

Expédition conjointe de l’amiral français d’Estaing avec le général américain Sullivan à Newport RI août 1778

Expédition conjointe de l’amiral français d’Estaing avec le général américain Sullivan à Newport RI août 1778

À la fin de 1777, Howe démissionne et est remplacé par Sir Henry Clinton le 24 mai 1778 ; avec l’entrée française dans la guerre, il reçoit l’ordre de consolider ses forces à New York. [201] Le 18 juin, les Britanniques ont quitté Philadelphie avec les Américains revigorés à leur poursuite; la bataille de Monmouth le 28 juin n’a pas été concluante mais a remonté le moral des Patriotes. Washington avait rallié les régiments brisés de Charles Lee, les Continentaux avaient repoussé les charges à la baïonnette britanniques, l’arrière-garde britannique avait perdu peut-être 50 % de pertes supplémentaires et les Américains tenaient le terrain en fin de compte. Ce minuit-là, Clinton nouvellement installé a poursuivi sa retraite à New York. [203]

Une force navale française sous l’amiral Charles Henri Hector d’Estaing a été envoyée pour aider Washington; décidant que New York était une cible trop redoutable, ils lancèrent en août une attaque combinée sur Newport, le général John Sullivan commandant les forces terrestres. [204] La Bataille résultante de Rhode Island était indécise; gravement endommagé par une tempête, les Français se retirent pour ne pas mettre leurs navires en danger. [205] D’autres activités se sont limitées aux raids britanniques sur Chestnut Neck et Little Egg Harbor en octobre. [206]

En juillet 1779, les Américains s’emparèrent des positions britanniques à Stony Point et Paulus Hook . [207] Clinton a tenté en vain de tenter Washington dans un engagement décisif en envoyant le général William Tryon faire un raid dans le Connecticut . [208] En juillet, une grande opération navale américaine, l’ expédition Penobscot , tente de reprendre le Maine , alors partie du Massachusetts, mais est vaincue. [209] Les incursions persistantes d’ Iroquois le long de la frontière avec le Québec ont mené à l’ expédition punitive de Sullivan en avril de 1779, détruisant beaucoup de règlements mais ne les arrêtant pas. [210]

Au cours de l’hiver 1779-1780, l’armée continentale a subi de plus grandes difficultés qu’à Valley Forge. [211] Le moral était faible, le soutien public s’est effondré pendant la longue guerre, le dollar continental était pratiquement sans valeur, l’armée était en proie à des problèmes d’approvisionnement, la désertion était courante et des mutineries se sont produites dans les régiments de la Pennsylvania Line et de la New Jersey Line . au début de 1780. [212]

Continentaux repoussant les Britanniques en

Continentaux repoussant les Britanniques en

juin 1780 à Springfield

“Donnez-leur des watts, les garçons!”

En juin 1780, Clinton envoya 6 000 hommes sous Wilhelm von Knyphausen pour reprendre le New Jersey, mais ils furent arrêtés par la milice locale lors de la bataille de Connecticut Farms ; bien que les Américains se soient retirés, Knyphausen a estimé qu’il n’était pas assez fort pour engager la force principale de Washington et s’est retiré. [213] Une deuxième tentative deux semaines plus tard s’est terminée par une défaite britannique à la bataille de Springfield , mettant ainsi fin à leurs ambitions dans le New Jersey. [214] En juillet, Washington nomma Benedict Arnold commandant de West Point ; sa tentative de trahir le fort aux Britanniques a échoué en raison d’une planification incompétente, et le complot a été révélé lorsque son contact britannique John Andréa été capturé et exécuté plus tard. [215] Arnold s’enfuit à New York et changea de camp, action justifiée dans un pamphlet adressé « Aux habitants de l’Amérique » ; les Patriotes ont condamné sa trahison, alors qu’il se trouvait presque aussi impopulaire auprès des Britanniques. [216]

Le gouverneur du Québec Hamilton se rend au colonel Clark à Vincennes, juillet 1779 La

Le gouverneur du Québec Hamilton se rend au colonel Clark à Vincennes, juillet 1779 La

Virginie incorpore son comté de l’Ohio

La guerre à l’ouest des Appalaches se limitait en grande partie à des escarmouches et à des raids. En février 1778, une expédition de la milice pour détruire les fournitures militaires britanniques dans les colonies le long de la rivière Cuyahoga a été interrompue par des conditions météorologiques défavorables. [217] Plus tard dans l’année, une deuxième campagne a été entreprise pour saisir le Pays d’Illinois des Britanniques. La milice de Virginie, les colons canadiens et les alliés indiens commandés par le colonel George Rogers Clark ont capturé Kaskaskia le 4 juillet, puis ont sécurisé Vincennes , bien que Vincennes ait été repris par le gouverneur du Québec, Henry Hamilton .. Au début de 1779, les Virginiens contre-attaquent lors du siège de Fort Vincennes et font prisonnier Hamilton. Clark a sécurisé l’ouest du Québec britannique en tant que Territoire du Nord-Ouest américain dans le traité de Paris concluant la guerre. [218]

Le 25 mai 1780, le colonel britannique Henry Bird envahit le Kentucky dans le cadre d’une opération plus vaste visant à éliminer la résistance américaine de Québec à la côte du golfe. Leur avance de Pensacola sur la Nouvelle-Orléans a été vaincue par l’offensive du gouverneur espagnol Gálvez sur Mobile. Des attaques britanniques simultanées ont été repoussées contre Saint-Louis par le lieutenant-gouverneur espagnol de Leyba et contre le palais de justice du comté de Virginie à Cahokia par le lieutenant-colonel Clark. L’initiative britannique sous Bird de Detroit a pris fin à l’approche selon la rumeur de Clark. [aa] L’ampleur de la violence dans la vallée de la rivière Licking , comme lors de la bataille de Blue Licks, était extrême “même pour les normes frontalières”. Cela a conduit des hommes des colonies anglaises et allemandes à rejoindre la milice de Clark lorsque les Britanniques et leurs soldats allemands engagés se sont retirés dans les Grands Lacs. [219] Les Américains ont répondu par une offensive majeure le long de la rivière Mad en août qui a rencontré un certain succès lors de la bataille de Piqua mais n’a pas mis fin aux raids indiens. [220]

Le soldat français Augustin de La Balme a dirigé une milice canadienne dans une tentative de capturer Detroit, mais ils se sont dispersés lorsque des indigènes de Miami dirigés par Little Turtle ont attaqué les colons campés le 5 novembre. [221] [ab] La guerre dans l’ouest était devenue une impasse avec la garnison britannique assise à Detroit et les Virginiens développant des colonies vers l’ouest au nord de la rivière Ohio face à la résistance indienne alliée aux Britanniques. [223]

Guerre dans le sud

Siège britannique de Charleston,

Siège britannique de Charleston,

pire défaite américaine de la guerre, mai 1780

La «stratégie du sud» a été développée par Lord Germain, sur la base de la contribution de loyalistes basés à Londres comme Joseph Galloway. Ils ont fait valoir que cela n’avait aucun sens de combattre les Patriotes dans le nord où ils étaient les plus forts, alors que l’économie de la Nouvelle-Angleterre dépendait du commerce avec la Grande-Bretagne, quel que soit celui qui la gouvernait. D’un autre côté, les droits sur le tabac rendaient le Sud beaucoup plus rentable pour la Grande-Bretagne, tandis que le soutien local signifiait que sa sécurisation nécessitait un petit nombre de troupes régulières. La victoire laisserait des États-Unis tronqués face aux possessions britanniques au sud, au Canada au nord et à l’Ohio à leur frontière ouest; avec la côte atlantique contrôlée par la Royal Navy, le Congrès serait obligé d’accepter les conditions. Cependant, les hypothèses sur le niveau de soutien loyaliste se sont révélées extrêmement optimistes. [224]

Germain ordonna donc à Augustine Prévost , le commandant britannique en Floride orientale , d’avancer en Géorgie en décembre 1778. Le lieutenant-colonel Archibald Campbell , un officier expérimenté fait prisonnier plus tôt dans la guerre avant d’être échangé contre Ethan Allen, captura Savannah le 29 décembre 1778. Il recruta une milice loyaliste de près de 1 100 personnes, dont beaucoup ne se seraient jointes qu’après que Campbell eut menacé de confisquer leurs biens. [225] Une motivation et un entraînement médiocres en ont fait des troupes peu fiables, comme en témoigne leur défaite contre la milice patriote à la bataille de Kettle Creek le 14 février 1779, bien que cela ait été compensé par la victoire britannique àBrier Creek le 3 mars. [226]

En juin, Prévost a lancé un assaut avorté sur Charleston, avant de se retirer à Savannah, une opération notoire pour le pillage généralisé par les troupes britanniques qui a enragé à la fois les loyalistes et les patriotes. En octobre, une opération conjointe française et américaine sous l’amiral d’Estaing et le général Benjamin Lincoln n’a pas réussi à reprendre Savannah . [227] Prévost est remplacé par Lord Cornwallis , qui assume la responsabilité de la stratégie de Germain ; il s’est vite rendu compte que les estimations du soutien loyaliste étaient considérablement surestimées et qu’il avait besoin d’un nombre beaucoup plus important de forces régulières. [228]

La cavalerie américaine et britannique affrontent

La cavalerie américaine et britannique affrontent

les déroutes américaines Bataille de la Légion britannique

de Cowpens , janvier 1781

Renforcées par Clinton, ses troupes s’emparèrent de Charleston en mai 1780, infligeant la plus grave défaite patriote de la guerre ; plus de 5 000 prisonniers ont été faits et l’armée continentale dans le sud a été effectivement détruite. Le 29 mai, le régulier loyaliste Banastre Tarleton a vaincu une force américaine de 400 hommes à la bataille de Waxhaws ; plus de 120 ont été tués, dont beaucoup après s’être rendus. La responsabilité est contestée, les loyalistes affirmant que Tarleton a été abattu lors de la négociation des conditions de reddition, mais il a ensuite été utilisé comme outil de recrutement par les patriotes. [229]

Clinton retourna à New York, laissant Cornwallis superviser le sud ; malgré leur succès, les deux hommes sont partis à peine en bons termes, avec des conséquences désastreuses pour la conduite future de la guerre. [230] La stratégie du Sud dépendait du soutien local, mais celui-ci a été sapé par une série de mesures coercitives. Auparavant, les Patriotes capturés étaient renvoyés chez eux après avoir juré de ne pas prendre les armes contre le roi ; ils sont désormais tenus de combattre leurs anciens camarades, tandis que la confiscation des plantations appartenant aux Patriotes amène les « grands » autrefois neutres à se ranger à leurs côtés. [231] Escarmouches à Williamson’s Plantation , Cedar Springs, Rocky Mount et Hanging Rocka signalé une résistance généralisée aux nouveaux serments dans toute la Caroline du Sud. [232]

En juillet, le Congrès a nommé le général Horatio Gates commandant dans le sud ; il a été vaincu à la bataille de Camden le 16 août, laissant Cornwallis libre d’entrer en Caroline du Nord. [233] En dépit du succès de champ de bataille, les Britanniques ne pouvaient pas contrôler la campagne et les attaques de Patriot ont continué; avant de se déplacer vers le nord, Cornwallis a envoyé la milice loyaliste sous le commandement du major Patrick Ferguson pour couvrir son flanc gauche, laissant leurs forces trop éloignées pour se soutenir mutuellement. [234] Début octobre, Ferguson est vaincu à la bataille de Kings Mountain , dispersant la résistance loyaliste organisée dans la région. [235]Malgré cela, Cornwallis a continué en Caroline du Nord dans l’espoir d’un soutien loyaliste, tandis que Washington a remplacé Gates par le général Nathanael Greene en décembre 1780. [236]

1st Maryland Regiment en ligne

1st Maryland Regiment en ligne

Guilford Court House , mars 1781

Greene a divisé son armée, menant sa force principale au sud-est poursuivie par Cornwallis; un détachement a été envoyé au sud-ouest sous Daniel Morgan , qui a vaincu la Légion britannique de Tarleton à Cowpens le 17 janvier 1781, l’éliminant presque comme force de combat. [237] Les Patriotes détenaient désormais l’initiative dans le sud, à l’exception d’un raid sur Richmond mené par Benedict Arnold en janvier 1781. [238] Greene mena Cornwallis dans une série de contremarches autour de la Caroline du Nord ; début mars, les Britanniques étaient épuisés et à court de ravitaillement et Greene se sentait assez fort pour combattre la bataille de Guilford Court Housele 15 mars. Bien que victorieux, Cornwallis subit de lourdes pertes et se retira à Wilmington, en Caroline du Nord, à la recherche de ravitaillement et de renforts. [239]

Les Patriotes contrôlaient désormais la plupart des Carolines et de la Géorgie en dehors des zones côtières; après un renversement mineur à la bataille de Hobkirk’s Hill , ils ont repris Fort Watson et Fort Motte le 15 avril. [240] Le 6 juin, le brigadier général Andrew Pickens a capturé Augusta , laissant les Britanniques en Géorgie confinés à Charleston et Savannah. [241] L’hypothèse que les loyalistes feraient la plupart des combats a laissé les Britanniques à court de troupes et les victoires sur le champ de bataille se sont faites au prix de pertes qu’ils ne pouvaient pas remplacer. Malgré l’arrêt de l’avance de Greene à la bataille d’Eutaw Springsle 8 septembre, Cornwallis se retire à Charleston avec peu à montrer pour sa campagne. [242]

Campagne de l’Ouest

| Conquérants du bassin britannique du Mississippi |

|

Lorsque l’Espagne a rejoint la guerre de la France contre la Grande-Bretagne en 1779, leur traité excluait spécifiquement l’action militaire espagnole en Amérique du Nord. Cependant, dès le début de la guerre, Bernardo de Gálvez , le gouverneur de la Louisiane espagnole , a permis aux Américains d’importer des fournitures et des munitions à la Nouvelle-Orléans , puis de les expédier à Pittsburgh . [243] Cela a fourni une voie de transport alternative pour l’armée continentale, contournant le blocus britannique de la côte atlantique. [244]

Le commerce a été organisé par Oliver Pollock , un marchand prospère à La Havane et à la Nouvelle-Orléans qui a été nommé “agent commercial” des États-Unis. [245] Il a également aidé à soutenir la campagne américaine dans l’ouest ; lors de la campagne de l’Illinois de 1778 , la milice dirigée par le général George Rogers Clark a débarrassé les Britanniques de ce qui faisait alors partie du Québec , créant le comté d’Illinois, en Virginie . [246]

Malgré la neutralité officielle, Gálvez a lancé des opérations offensives contre les avant-postes britanniques. [247] Tout d’abord, il a nettoyé les garnisons britanniques à Baton Rouge , en Louisiane , à Fort Bute et à Natchez , au Mississippi , et a capturé cinq forts. [248] Ce faisant, Gálvez a ouvert la navigation sur le fleuve Mississippi au nord jusqu’à la colonie américaine de Pittsburg. [249]

En 1781, Galvez et Pollock ont fait campagne vers l’est le long de la côte du golfe pour sécuriser l’ouest de la Floride, y compris Mobile et Pensacola , détenus par les Britanniques . [250] Les opérations espagnoles ont paralysé l’approvisionnement britannique en armements aux alliés indiens britanniques, ce qui a effectivement suspendu une alliance militaire pour attaquer les colons entre le fleuve Mississippi et les Appalaches. [251] [ac]

Défaite britannique aux États-Unis

la flotte française (g.) engage les Britanniques ;

la flotte française (g.) engage les Britanniques ;

Le français transporte des approvisionnements terrestres derrière

la bataille de la Chesapeake , septembre 1781

Clinton a passé la majeure partie de 1781 à New York ; il n’a pas réussi à construire une stratégie opérationnelle cohérente, en partie à cause de sa relation difficile avec l’amiral Marriot Arbuthnot . [252] À Charleston, Cornwallis développa indépendamment un plan agressif pour une campagne en Virginie, dont il espérait qu’il isolerait l’armée de Greene dans les Carolines et provoquerait l’effondrement de la résistance patriote dans le Sud. Cela a été approuvé par Lord Germain à Londres, mais aucun d’eux n’a informé Clinton. [253]

Washington et Rochambeau ont maintenant discuté de leurs options ; le premier voulait attaquer New York, le second la Virginie, où les forces de Cornwallis étaient moins bien établies et donc plus faciles à vaincre. [254] Washington a finalement cédé et Lafayette a emmené une force franco-américaine combinée en Virginie, [255] mais Clinton a mal interprété ses mouvements comme des préparatifs pour une attaque contre New York. Préoccupé par cette menace, il ordonna à Cornwallis d’établir une base maritime fortifiée où la Royal Navy pourrait évacuer ses troupes pour aider à défendre New York. [256]

Lorsque Lafayette est entré en Virginie, Cornwallis s’est conformé aux ordres de Clinton et s’est retiré à Yorktown , où il a construit de solides défenses et a attendu son évacuation. [257] Un accord de la marine espagnole pour défendre les Antilles françaises a permis à l’amiral de Grasse de déménager sur la côte atlantique, un mouvement qu’Arbuthnot n’avait pas prévu. [252] Cela a fourni un soutien naval à Lafayette, tandis que l’échec des opérations combinées précédentes à Newport et Savannah signifiait que leur coordination était planifiée plus soigneusement. [258] Malgré les insistances répétées de ses subordonnés, Cornwallis n’a fait aucune tentative pour engager Lafayette avant qu’il ne puisse établir des lignes de siège. [259]Pire encore, s’attendant à se retirer dans quelques jours, il abandonna les défenses extérieures, qui furent rapidement occupées par les assiégeants et précipitèrent la défaite britannique. [260]

Cornwallis se rend, Yorktown en octobre 1781

Cornwallis se rend, Yorktown en octobre 1781

, son armée navigue vers New York ; Clinton remplacé;

Le Parlement met fin à l’action offensive en N.Am.

Le 31 août, une flotte britannique commandée par Thomas Graves quitte New York pour Yorktown. [261] Après avoir débarqué des troupes et des munitions pour les assiégeants le 30 août, de Grasse était resté dans la baie de Chesapeake et l’avait intercepté le 5 septembre ; bien que la bataille de Chesapeake ait été indécise en termes de pertes, Graves a été contraint de battre en retraite, laissant Cornwallis isolé. [262] Une tentative d’évasion sur la rivière York à Gloucester Point a échoué en raison du mauvais temps. [263]Sous un bombardement intense avec des approvisionnements en diminution, Cornwallis sentit que sa situation était désespérée et le 16 octobre envoya des émissaires à Washington pour négocier la reddition; après douze heures de négociations, celles-ci ont été finalisées le lendemain. [264] La responsabilité de la défaite a fait l’objet d’un débat public féroce entre Cornwallis, Clinton et Germain. Malgré les critiques de ses officiers subalternes, Cornwallis a conservé la confiance de ses pairs et a ensuite occupé une série de postes gouvernementaux supérieurs; Clinton a finalement pris la majeure partie du blâme et a passé le reste de sa vie dans l’obscurité. [265]

À la suite de Yorktown, les forces américaines ont été chargées de superviser l’armistice entre Washington et Clinton conclu pour faciliter le départ des Britanniques à la suite de la loi de janvier 1782 du Parlement interdisant toute nouvelle action offensive britannique en Amérique du Nord. Les négociations anglo-américaines à Paris aboutirent à des préliminaires signés en novembre 1782 reconnaissant l’indépendance des États-Unis. L’objectif de guerre promulgué par le Congrès pour que les Britanniques se retirent de leurs revendications nord-américaines à céder aux États-Unis a été atteint pour les villes côtières par étapes. [266]

Dans le sud, les généraux Greene et Wayne ont vaguement investi les Britanniques qui se retiraient à Savanna et Charleston. Là, ils ont observé que les Britanniques enlevaient finalement leurs réguliers de Charleston le 14 décembre 1782. [267] Les milices provinciales loyalistes de Blancs et de Noirs libres, ainsi que les Loyalistes avec leurs esclaves ont été transportés dans une réinstallation en Nouvelle-Écosse et dans les Caraïbes britanniques. [ad] Les alliés amérindiens des Britanniques et certains Noirs libérés ont dû s’échapper sans aide à travers les lignes américaines.

Washington a déplacé son armée à New Windsor sur la rivière Hudson à environ soixante miles au nord de New York, [268] et là, la substance de l’armée américaine a été renvoyée chez elle avec des officiers à demi-solde jusqu’à ce que le traité de Paris mette officiellement fin à la guerre en septembre . 3, 1783. À cette époque, le Congrès a mis hors service les régiments de l’armée continentale de Washington et a commencé à accorder des concessions de terres aux anciens combattants des Territoires du Nord-Ouest pour leur service de guerre. La dernière de l’occupation britannique de New York prit fin le 25 novembre 1783, avec le départ du remplaçant de Clinton, le général Sir Guy Carleton . [269]

Stratégie et commandants

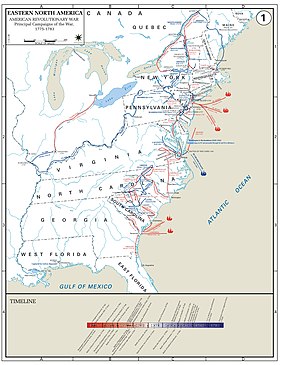

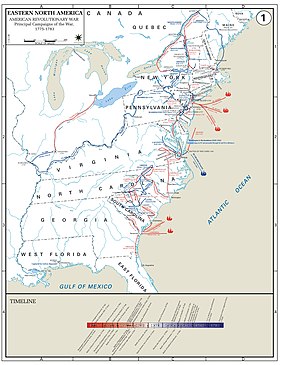

Campagnes principales de la Révolution américaine. [270] Mouvement britannique (rouge) et américain (bleu)

Campagnes principales de la Révolution américaine. [270] Mouvement britannique (rouge) et américain (bleu)

La chronologie montre que les Britanniques ont remporté la plupart des batailles au cours de la première mi-temps ; Les Américains ont gagné le plus dans la seconde.

Pour gagner leur insurrection, les Américains devaient survivre à la volonté britannique de poursuivre le combat. Pour restaurer l’empire, les Britanniques ont dû vaincre l’armée continentale dans les premiers mois et obliger le Congrès à se dissoudre. [271] L’historien Terry M. Mays identifie trois types de guerre distincts, le premier étant un conflit colonial dans lequel les objections à la réglementation commerciale impériale étaient aussi importantes que la politique fiscale. La seconde était une guerre civile avec les treize États divisés entre les patriotes, les loyalistes et ceux qui préféraient rester neutres. Particulièrement dans le sud, de nombreuses batailles ont eu lieu entre patriotes et loyalistes sans implication britannique, entraînant des divisions qui se sont poursuivies après l’accession à l’indépendance. [272]

Le troisième élément était une guerre mondiale entre la France, l’Espagne, la République néerlandaise et la Grande-Bretagne, avec l’Amérique comme l’un des nombreux théâtres différents. [272] Après être entrée en guerre en 1778, la France a fourni aux Américains de l’argent, des armes, des soldats et une assistance navale, tandis que les troupes françaises combattaient sous le commandement américain en Amérique du Nord. Bien que l’Espagne n’ait pas officiellement rejoint la guerre en Amérique, elle a donné accès au fleuve Mississippi et, en capturant les possessions britanniques sur le golfe du Mexique, a refusé des bases à la Royal Navy, ainsi qu’en reprenant Minorque et en assiégeant Gibraltar en Europe. [273]

Bien que la République néerlandaise ne soit plus une puissance majeure, avant 1774, elle dominait toujours le commerce de transport européen et les marchands néerlandais réalisaient de gros bénéfices en expédiant des munitions fournies par la France aux Patriotes. Cela a pris fin lorsque la Grande-Bretagne a déclaré la guerre en décembre 1780 et le conflit s’est avéré désastreux pour leur économie. [274] Les Néerlandais ont également été exclus de la Première Ligue de neutralité armée , formée par la Russie, la Suède et le Danemark en mars 1780 pour protéger les navires neutres contre l’arrêt et la recherche de contrebande par la Grande-Bretagne et la France. [194] Bien que d’effet limité, ces interventions ont forcé les Britanniques à détourner des hommes et des ressources de l’Amérique du Nord. [76]

Stratégie américaine

Densité de population britannique américaine

Densité de population britannique américaine

densités les plus élevées à proximité des ports en 1775

Le Congrès avait de multiples avantages si la rébellion se transformait en une guerre prolongée. Leurs populations étatiques prospères dépendaient de la production locale pour la nourriture et les fournitures plutôt que des importations de leur mère patrie qui se trouvaient à six à douze semaines de navigation. Ils étaient répartis sur la majeure partie de la côte nord-américaine de l’Atlantique, s’étendant sur 1 000 milles. La plupart des fermes étaient éloignées des ports maritimes et le contrôle de quatre ou cinq grands ports ne permettait pas aux armées britanniques de contrôler les zones intérieures. Chaque État avait mis en place des systèmes de distribution internes. [275]

Chaque ancienne colonie avait un système établi de longue date de milice locale, testé au combat pour soutenir les réguliers britanniques treize ans auparavant pour assurer un empire britannique élargi. Ensemble, ils ont emporté les revendications françaises en Amérique du Nord à l’ouest jusqu’au fleuve Mississippi pendant la guerre française et indienne . Les législatures des États ont financé et contrôlé de manière indépendante leurs milices locales. Pendant la Révolution américaine , ils ont formé et fourni des régiments de la ligne continentale à l’armée régulière, chacun avec son propre corps d’officiers d’État. [275] La motivation était aussi un atout majeur : chaque capitale coloniale avait ses propres journaux et imprimeurs, et les Patriotes avaient plus de soutien populaire que les Loyalistes. Les Britanniques espéraient que les loyalistes feraient une grande partie des combats, mais ils combattirent moins que prévu. [12]

Armée continentale

Le général Washington commandant l’ armée continentale

Le général Washington commandant l’ armée continentale

Lorsque la guerre a commencé, le Congrès n’avait pas d’armée ou de marine professionnelle, et chaque colonie ne maintenait que des milices locales. Les miliciens étaient légèrement armés, avaient peu d’entraînement et n’avaient généralement pas d’uniforme. Leurs unités ne servaient que quelques semaines ou mois à la fois et manquaient de l’entraînement et de la discipline de soldats plus expérimentés. Les milices locales du comté étaient réticentes à voyager loin de chez elles et elles n’étaient pas disponibles pour des opérations prolongées. [276] Pour compenser cela, le Congrès a créé une force régulière connue sous le nom d’armée continentale le 14 juin 1775, à l’origine de l’ armée américaine moderne., et nomme Washington commandant en chef. Cependant, il a beaucoup souffert de l’absence d’un programme de formation efficace et d’officiers et de sergents largement inexpérimentés, compensés par quelques officiers supérieurs. [277]

Chaque législature d’État a nommé des officiers pour les milices de comté et d’État et leurs officiers régimentaires de la ligne continentale; bien que Washington ait été tenu d’accepter les nominations au Congrès, il était toujours autorisé à choisir et à commander ses propres généraux, tels que Nathanael Greene , son chef d’artillerie, Henry Knox , et Alexander Hamilton , le chef d’état-major. [278] L’une des recrues les plus réussies de Washington au poste d’officier général était le baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben , un vétéran de l’état-major prussien qui a écrit le Revolutionary War Drill Manual . [277]Le développement de l’armée continentale était toujours un travail en cours et Washington a utilisé à la fois ses réguliers et sa milice d’État tout au long de la guerre; lorsqu’elle est correctement employée, la combinaison leur permet de submerger des forces britanniques plus petites, comme à Concord, Boston, Bennington et Saratoga. Les deux parties ont utilisé la guerre partisane, mais les milices d’État ont efficacement réprimé l’activité loyaliste lorsque les réguliers britanniques n’étaient pas dans la région. [276] [ae]

Washington a conçu la stratégie militaire globale de la guerre en coopération avec le Congrès, a établi le principe de la suprématie civile dans les affaires militaires, a personnellement recruté son corps d’officiers supérieurs et a maintenu les États concentrés sur un objectif commun. [281] Pendant les trois premières années jusqu’après Valley Forge , l’armée continentale a été largement complétée par des milices d’État locales. Au départ, Washington a employé les officiers inexpérimentés et les troupes non entraînées dans des stratégies fabianes plutôt que de risquer des assauts frontaux contre les soldats et officiers professionnels britanniques. [282]Au cours de toute la guerre, Washington a perdu plus de batailles qu’il n’en a gagnées, mais il n’a jamais rendu ses troupes et maintenu une force de combat face aux armées de campagne britanniques et n’a jamais renoncé à se battre pour la cause américaine. [283]

Image de divers uniformes de l’armée continentale

Image de divers uniformes de l’armée continentale