Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales

La Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales , officiellement la United East India Company ( néerlandais : Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie ; [f] VOC ), était une société multinationale fondée par une consolidation dirigée par le gouvernement de plusieurs sociétés commerciales néerlandaises rivales ( voorcompagnie ën ) au début du 17e siècle. On pense que c’est la plus grande entreprise à avoir jamais existé dans l’histoire enregistrée. [9] [10] Il a été créé le 20 mars 1602, en tant que société à charte pour commercer avec l’Inde moghole [11] [contesté – discuter ]audébut de la période moderne, d’où 50 % des textiles et 80 % des soieries étaient importés,[ où ? ]principalement de sa région la plus développée connue sous le nom deBengal Subah. [12][13][14][15][16]En outre, la société a fait du commerce avecles pays d’Asie du Sud-Estindianisésgouvernement néerlandaisaccordé un monopole de 21 ans sur lecommerce des épices.

|

|

| Nom natif |

|

|---|---|

| Taper |

|

| Industrie | Proto-conglomérat [b] |

| Prédécesseur | Voorcompagnie ën / Pré-compagnies (1594–1602) [c]

|

| Fondé | 20 mars 1602 , [8] par une consolidation dirigée par le gouvernement des voorcompagnieën / pré-compagnies (1602-03-20) |

| Fondateur | Johan van Oldenbarnevelt et les États généraux |

| Défunt | 31 décembre 1799 (1799-12-31) |

| Sort | Dissous et nationalisé en tant qu’Indes orientales néerlandaises |

| Quartier général |

|

| Zone servie |

|

| Personnes clés |

|

| Des produits | Épices , [2] soie, porcelaine , métaux , bétail, thé, céréales, riz, soja , canne à sucre , [3] [4] vin , [5] [6] [7] café |

La “United East India Company”, ou “United East Indies Company” (également connue sous l’abréviation “VOC” en néerlandais) était l’idée originale de Johan van Oldenbarnevelt , le principal homme d’État de la République néerlandaise.

La “United East India Company”, ou “United East Indies Company” (également connue sous l’abréviation “VOC” en néerlandais) était l’idée originale de Johan van Oldenbarnevelt , le principal homme d’État de la République néerlandaise.  QG d’Amsterdam VOC

QG d’Amsterdam VOC  Réplique du navire VOC Duyfken sous voiles

Réplique du navire VOC Duyfken sous voiles

L’entreprise a souvent été qualifiée de société commerciale (c’est-à-dire une société de marchands qui achètent et vendent des biens produits par d’autres personnes) ou parfois de compagnie maritime . Cependant, le VOC était en fait un modèle d’entreprise moderne de chaîne d’approvisionnement mondiale intégrée verticalement [2] [5] et un proto- conglomérat , se diversifiant dans de multiples activités commerciales et industrielles telles que le commerce international (en particulier le commerce intra-asiatique), [1] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] construction navale, production et commerce d’ épices des Indes orientales , [2] café indonésien , Canne à sucre de Formose , [3] [4] et vin sud-africain . [5] [6] [7] L’entreprise était un employeur transcontinental et une entreprise pionnière de l’ investissement étranger direct sortant au début du monde moderne. À l’aube du capitalisme moderne , partout où le capital néerlandais est allé, les caractéristiques urbaines ont été développées, les activités économiques se sont développées, de nouvelles industries ont été créées, de nouveaux emplois ont été créés, des sociétés commerciales ont fonctionné, des marécages ont été asséchés, des mines ont été ouvertes, des forêts ont été exploitées, des canaux ont été construits, des moulins ont été transformés et des navires. ont été construits. [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] Au début de la période moderne, les Néerlandais ont été les pionniersdes investisseurs et des capitalistes qui ont relevé le potentiel commercial et industriel de terres sous-développées ou non dont ils ont exploité les ressources, tant bien que mal. Par exemple, les économies indigènes de Taïwan et d’Afrique du Sud avant l’ère VOC étaient en grande partie rurales. Ce sont les employés de VOC qui ont établi et développé les premières zones urbaines modernes de l’histoire de Taïwan ( Tainan ) et de l’Afrique du Sud ( Le Cap et Stellenbosch ).

Fondée en 1602, la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (VOC) a commencé comme négociant en épices . La même année, la VOC a entrepris la première introduction en bourse enregistrée au monde . ” L’ introduction en bourse ” a permis à l’entreprise de lever rapidement la colossale somme de 6,5 millions de florins . Les innovations institutionnelles et les pratiques commerciales de la VOC [27] [28] [29] ont jeté les bases de la montée des sociétés mondiales modernes et des marchés de capitaux qui dominent désormais les systèmes économiques mondiaux. [30]

Fondée en 1602, la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (VOC) a commencé comme négociant en épices . La même année, la VOC a entrepris la première introduction en bourse enregistrée au monde . ” L’ introduction en bourse ” a permis à l’entreprise de lever rapidement la colossale somme de 6,5 millions de florins . Les innovations institutionnelles et les pratiques commerciales de la VOC [27] [28] [29] ont jeté les bases de la montée des sociétés mondiales modernes et des marchés de capitaux qui dominent désormais les systèmes économiques mondiaux. [30]

Au début des années 1600, en émettant à grande échelle des obligations et des actions auprès du grand public, [g] VOC est devenue la première société publique officiellement cotée au monde . [h] [i] [32] [33] [34] [35] [ citation complète nécessaire ] [36] [37] [38] Avec ses innovations institutionnelles pionnières et ses rôles puissants dans l’histoire des affaires mondiales, l’entreprise est souvent considérée par beaucoup d’être le précurseur des sociétés modernes. À bien des égards, les entreprises modernes sont toutes les « descendantes directes » du modèle VOC. [28] [ citation complète nécessaire ] [39][40] [41] [42] [ citation complète nécessaire ] Ses innovations institutionnelles et ses pratiques commerciales du XVIIe siècle ont jeté les bases de la montée des sociétés mondiales géantes au cours des siècles suivants [27] [28] [29] [43] – comme une force socio-politico-économique hautement significative et formidable du monde moderne [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] – pour devenir le facteur dominant dans presque tous les systèmes économiques aujourd’hui. Il a également servi de modèle direct pour la reconstruction organisationnelle de la Compagnie anglaise / britannique des Indes orientales en 1657. [49] [50] [51] [52] [38][53] La société, pendant près de 200 ans de son existence (1602-1800), s’était effectivement transformée d’une personne morale en un État ou un empire à part entière. [j] L’une des entreprises commerciales les plus influentes et les plus étudiées de l’histoire , le monde du VOC a fait l’objet d’une grande quantité de littérature qui comprend à la fois des œuvres de fiction et de non-fiction.

Assiette en porcelaine d’exportation japonaise ( articles Arita ) avec le logo du monogramme du COV

Assiette en porcelaine d’exportation japonaise ( articles Arita ) avec le logo du monogramme du COV

L’entreprise était historiquement une société-État exemplaire [k] plutôt qu’une société purement à but lucratif . À l’origine une entreprise militaro-commerciale soutenue par le gouvernement, le VOC était le fruit de la guerre de l’homme d’État républicain néerlandais Johan van Oldenbarnevelt et des États généraux . Depuis sa création en 1602, la société n’était pas seulement une entreprise commerciale, mais aussi un instrument de guerre efficace dans la guerre mondiale révolutionnaire de la jeune République néerlandaise contre le puissant Empire espagnol et l’Union ibérique (1579-1648). En 1619, la société a établi de force une position centrale dans la ville javanaise de Jayakarta, changeant le nom en Batavia( Jakarta d’aujourd’hui ). Au cours des deux siècles suivants, la société a acquis des ports supplémentaires comme bases commerciales et a sauvegardé ses intérêts en prenant le contrôle du territoire environnant. [57] Pour garantir son approvisionnement, la société a établi des positions dans de nombreux pays et est devenue l’un des premiers pionniers de l’investissement direct étranger à l’étranger . [l] Dans ses colonies étrangères, le VOC possédait des pouvoirs quasi-gouvernementaux, y compris la capacité de faire la guerre, d’emprisonner et d’exécuter des condamnés, [61] de négocier des traités, de frapper ses propres pièces et d’établir des colonies . [62]Avec l’importance croissante des postes à l’étranger, l’entreprise est souvent considérée comme la première véritable société transnationale au monde . [m] [63] Avec la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales (WIC/GWC), la VOC était considérée comme le bras international de la République néerlandaise et la puissance symbolique de l’ Empire néerlandais . Pour approfondir ses routes commerciales, les voyages d’exploration financés par le VOC, tels que ceux menés par Willem Janszoon ( Duyfken ), Henry Hudson ( Halve Maen ) et Abel Tasman , ont révélé des masses continentales largement inconnues au monde occidental. À l’ âge d’or de la cartographie néerlandaise( vers 1570-1670 ), les navigateurs et cartographes VOC ont contribué à façonner la connaissance géographique du monde tel que nous le connaissons aujourd’hui.

Les changements socio-économiques en Europe, le changement d’équilibre des pouvoirs et une gestion financière moins efficace ont entraîné un lent déclin du COV entre 1720 et 1799. Après la quatrième guerre anglo-néerlandaise financièrement désastreuse (1780–1784), l’entreprise a été nationalisée. en 1796, [64] et finalement dissous le 31 décembre 1799. Tous les actifs ont été repris par le gouvernement avec les territoires VOC devenant des colonies gouvernementales hollandaises.

Nom, logo et drapeau de l’entreprise

Plaque du XVIIe siècle à la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (VOC), Hoorn

Plaque du XVIIe siècle à la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (VOC), Hoorn

Le logo de la Chambre d’Amsterdam du VOC

Le logo de la Chambre d’Amsterdam du VOC

En néerlandais, le nom de la société est Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie ou Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, littéralement la “United East Indian Company”, qui est abrégé en VOC . Le logo monogramme de la société se composait d’un grand « V » majuscule avec un O sur la gauche et un C sur la moitié droite et était peut-être le premier logo d’entreprise mondialement reconnu . [39] Il est apparu sur divers articles d’entreprise, tels que des canonset pièces de monnaie. La première lettre de la ville natale de la chambre menant l’opération a été placée en haut. Le monogramme, la polyvalence, la flexibilité, la clarté, la simplicité, la symétrie, l’intemporalité et le symbolisme sont considérés comme des caractéristiques notables du logo conçu par des professionnels du VOC. Ces éléments ont assuré son succès à une époque où le concept d’ identité corporative était pratiquement inconnu. [39] [65] [66] Un vigneron australien a utilisé le logo VOC depuis la fin du 20e siècle, ayant réenregistré le nom de l’entreprise à cet effet. [67] Le drapeau de l’entreprise était rouge, blanc et bleu, avec le logo de l’entreprise brodé dessus. [ citation nécessaire ]

Partout dans le monde, et en particulier dans les pays anglophones, la VOC est largement connue sous le nom de «Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales». Le nom « Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales » est utilisé pour faire la distinction entre la Compagnie [britannique] des Indes orientales (EIC) et les autres sociétés des Indes orientales (telles que la Compagnie danoise des Indes orientales , la Compagnie française des Indes orientales , la Compagnie portugaise des Indes orientales et la Compagnie suédoise des Indes orientales ). Les noms alternatifs de la société qui ont été utilisés incluent la « Dutch East Indies Company », « United East India Company », « United East Indian Company », « United East Indies Company », « Jan Company » ou « Jan Compagnie ».

Histoire

Origines

Avant la révolte hollandaise , Anvers avait joué un rôle important en tant que centre de distribution dans le nord de l’Europe. Après 1591, cependant, les Portugais ont utilisé un syndicat international des Fuggers et Welsers allemands , et des entreprises espagnoles et italiennes, qui ont utilisé Hambourg comme port de base du nord pour distribuer leurs marchandises, excluant ainsi les marchands néerlandais du commerce. Dans le même temps, le système commercial portugais n’a pas été en mesure d’augmenter l’offre pour satisfaire la demande croissante, en particulier la demande de poivre. La demande d’épices était relativement inélastique ; par conséquent, chaque retard dans l’approvisionnement en poivre a provoqué une forte hausse des prix du poivre.

En 1580, la couronne portugaise était unie dans une union personnelle avec la couronne espagnole, avec laquelle la République néerlandaise était en guerre. L’ Empire portugais est donc devenu une cible appropriée pour les incursions militaires néerlandaises. Ces facteurs ont motivé les marchands néerlandais à se lancer eux-mêmes dans le commerce intercontinental des épices. De plus, un certain nombre de Néerlandais comme Jan Huyghen van Linschoten et Cornelis de Houtman ont obtenu une connaissance de première main des routes et pratiques commerciales portugaises «secrètes», offrant ainsi des opportunités. [70]

Siège social de VOC à Amsterdam

Siège social de VOC à Amsterdam

Le décor était ainsi planté pour l’expédition exploratoire de quatre navires de Frederick de Houtman en 1595 à Banten , le principal port de poivre de Java occidental, où ils se sont affrontés à la fois avec les Portugais et les Javanais indigènes. L’expédition de Houtman a ensuite navigué vers l’est le long de la côte nord de Java , perdant douze membres d’équipage lors d’une attaque javanaise à Sidayu et tuant un dirigeant local à Madura . La moitié de l’équipage a été perdue avant que l’expédition ne revienne aux Pays-Bas l’année suivante, mais avec suffisamment d’épices pour faire un profit considérable. [71]

Retour de la deuxième expédition en Asie de Jacob van Neck en 1599 par Cornelis Vroom

Retour de la deuxième expédition en Asie de Jacob van Neck en 1599 par Cornelis Vroom

En 1598, un nombre croissant de flottes ont été envoyées par des groupes de marchands concurrents de partout aux Pays-Bas. Certaines flottes ont été perdues, mais la plupart ont réussi, certains voyages produisant des profits élevés. En mars 1599, une flotte de huit navires sous Jacob van Neck fut la première flotte néerlandaise à atteindre les «îles aux épices» de Maluku (également connues sous le nom de Moluques), supprimant les intermédiaires javanais. Les navires retournèrent en Europe en 1599 et 1600 et l’expédition réalisa un bénéfice de 400 %. [71]

En 1600, les Néerlandais se sont associés aux musulmans hituais sur l’île d’Ambon dans une alliance anti-portugaise, en échange de laquelle les Néerlandais ont reçu le droit exclusif d’acheter des épices à Hitu. [72] Le contrôle hollandais d’Ambon a été réalisé quand les Portugais ont rendu leur fort dans Ambon à l’alliance Néerlandaise-Hituese. En 1613, les Néerlandais expulsèrent les Portugais de leur fort de Solor , mais une attaque portugaise ultérieure conduisit à un deuxième changement de mains; suite à cette deuxième réoccupation, les Hollandais s’emparèrent à nouveau de Solor en 1636. [72]

À l’est de Solor, sur l’île de Timor, les avancées hollandaises ont été stoppées par un groupe autonome et puissant d’Eurasiens portugais appelé les Topasses . Ils sont restés maîtres du commerce du bois de santal et leur résistance a duré tout au long des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, ce qui a permis au Timor portugais de rester sous la sphère de contrôle portugaise. [73] [74]

Années de formation

Reproduction d’un plan de la ville de Batavia v. 1627, collection Tropenmuseum

Reproduction d’un plan de la ville de Batavia v. 1627, collection Tropenmuseum

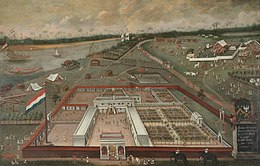

Batavia néerlandaise en 1681, construite dans l’actuel nord de Jakarta

Batavia néerlandaise en 1681, construite dans l’actuel nord de Jakarta

A l’époque, il était d’usage qu’une compagnie ne soit financée que pour la durée d’un seul voyage et soit liquidée au retour de la flotte. L’investissement dans ces expéditions était une entreprise à très haut risque, non seulement en raison des dangers habituels de piraterie, de maladie et de naufrage, mais aussi parce que l’interaction d’une demande inélastique et d’une offre relativement élastique [75] d’épices pouvait faire chuter les prix, ruinant ainsi perspectives de rentabilité. Pour gérer un tel risque, la formation d’un cartel pour contrôler l’offre semblerait logique. En 1600, les Anglais furent les premiers à adopter cette approche en regroupant leurs ressources dans une entreprise monopolistique, la Compagnie anglaise des Indes orientales , menaçant ainsi de ruine leurs concurrents hollandais. [76]

En 1602, le gouvernement néerlandais a emboîté le pas, parrainant la création d’une seule “Compagnie des Indes orientales unies” qui a également obtenu le monopole du commerce asiatique. [77] Pendant un certain temps au XVIIe siècle, il a pu monopoliser le commerce de la noix de muscade, du macis et des clous de girofle et vendre ces épices à travers les royaumes européens et l’empire moghol de l’empereur Akbar le Grand à 14 à 17 fois le prix qu’il a payé en Indonésie ; [78] tandis que les bénéfices néerlandais montaient en flèche, l’économie locale des îles aux épices était détruite. [ pourquoi ? ] Avec un capital de 6 440 200 florins , [79]la charte de la nouvelle société lui a donné le pouvoir de construire des forts, de maintenir des armées et de conclure des traités avec les dirigeants asiatiques. Il prévoyait une entreprise qui se poursuivrait pendant 21 ans, avec une comptabilité financière uniquement à la fin de chaque décennie. [76]

En février 1603, la compagnie s’empare du Santa Catarina , une caraque marchande portugaise de 1 500 tonneaux , au large de Singapour. [80] Elle était un prix si riche que le produit de sa vente a augmenté le capital du VOC de plus de 50%. [81]

Toujours en 1603, le premier poste de traite néerlandais permanent en Indonésie a été établi à Banten , Java occidental , et en 1611, un autre a été établi à Jayakarta (plus tard “Batavia” puis “Jakarta”). [82] En 1610, le VOC a établi le poste de gouverneur général pour contrôler plus fermement leurs affaires en Asie. Pour conseiller et contrôler le risque des gouverneurs généraux despotiques , un Conseil des Indes ( Raad van Indië ) est créé. Le gouverneur général est effectivement devenu le principal administrateur des activités du VOC en Asie, bien que le Heeren XVII, un corps de 17 actionnaires représentant différentes chambres, a continué à avoir officiellement le contrôle global. [72]

L’île d’Amboina , une estampe du XVIIe siècle, probablement anglaise

L’île d’Amboina , une estampe du XVIIe siècle, probablement anglaise

Le siège du VOC était situé à Ambon pendant les mandats des trois premiers gouverneurs généraux (1610-1619), mais ce n’était pas un endroit satisfaisant. Bien qu’il soit au centre des zones de production d’épices, il était loin des routes commerciales asiatiques et des autres zones d’activité des COV allant de l’Afrique à l’Inde en passant par le Japon. [83] [84] Un emplacement à l’ouest de l’archipel a donc été recherché. Le détroit de Malacca était stratégique mais est devenu dangereux après la conquête portugaise, et la première colonie permanente de COV à Banten était contrôlée par un puissant dirigeant local et soumise à une concurrence féroce de la part des commerçants chinois et anglais. [72]

En 1604, un deuxième voyage de la Compagnie anglaise des Indes orientales commandé par Sir Henry Middleton atteint les îles de Ternate , Tidore , Ambon et Banda . À Banda, ils ont rencontré une forte hostilité contre les COV, déclenchant une concurrence anglo-néerlandaise pour l’accès aux épices. [82] De 1611 à 1617, les Anglais établissent des comptoirs commerciaux à Sukadana (sud-ouest de Kalimantan ), Makassar , Jayakarta et Jepara à Java , et Aceh, Pariaman et Jambi à Sumatra, qui menaçait les ambitions néerlandaises d’un monopole sur le commerce des Indes orientales. [82]

En 1620, des accords diplomatiques en Europe inaugurent une période de coopération entre les Hollandais et les Anglais sur le commerce des épices. [82] Cela s’est terminé par un incident notoire mais contesté connu sous le nom de « massacre d’Amboine », où dix Anglais ont été arrêtés, jugés et décapités pour complot contre le gouvernement néerlandais. [85] Bien que cela ait provoqué l’indignation en Europe et une crise diplomatique, les Anglais se sont tranquillement retirés de la plupart de leurs activités indonésiennes (à l’exception du commerce à Banten) et se sont concentrés sur d’autres intérêts asiatiques.

Croissance

Tombes de dignitaires néerlandais dans les ruines de l’église Saint-Paul, Malacca , dans l’ancienne Malacca hollandaise

Tombes de dignitaires néerlandais dans les ruines de l’église Saint-Paul, Malacca , dans l’ancienne Malacca hollandaise

Usine de la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales à Hugli-Chuchura , Bengale moghol . Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665

Usine de la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales à Hugli-Chuchura , Bengale moghol . Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665

En 1619, Jan Pieterszoon Coen est nommé gouverneur général de la VOC. Il a vu la possibilité que le VOC devienne une puissance asiatique, à la fois politique et économique. Le 30 mai 1619, Coen, soutenu par une force de dix-neuf navires, prit d’assaut Jayakarta, chassant les forces de Banten; et des cendres a établi Batavia comme siège du VOC. Dans les années 1620, presque toute la population indigène des îles Banda a été chassée, morte de faim ou tuée dans une tentative de les remplacer par des plantations hollandaises. [86] Ces plantations servaient à cultiver la noix de muscadepour l’export. Coen espérait installer un grand nombre de colons néerlandais dans les Indes orientales, mais la mise en œuvre de cette politique ne s’est jamais concrétisée, principalement parce que très peu de Néerlandais étaient disposés à émigrer en Asie. [87]

Une autre des entreprises de Coen a eu plus de succès. Un problème majeur dans le commerce européen avec l’Asie à l’époque était que les Européens pouvaient offrir peu de biens que les consommateurs asiatiques voulaient, à l’exception de l’argent et de l’or. Les commerçants européens devaient donc payer les épices avec les métaux précieux, qui manquaient en Europe, à l’exception de l’Espagne et du Portugal. Les Néerlandais et les Anglais devaient l’obtenir en créant un excédent commercial avec les autres pays européens. Coen a découvert la solution évidente au problème : lancer un système commercial intra-asiatique, dont les bénéfices pourraient être utilisés pour financer le commerce des épices avec l’Europe. À long terme, cela a évité le besoin d’exportations de métaux précieux d’Europe, bien qu’au début cela ait nécessité la formation d’un important fonds de capital commercial aux Indes.[88]

Le COV s’échangeait dans toute l’Asie, bénéficiant principalement du Bengale . Les navires arrivant à Batavia en provenance des Pays-Bas transportaient des fournitures pour les colonies de COV en Asie. L’argent et le cuivre du Japon étaient utilisés pour commercer avec les empires les plus riches du monde, l’Inde moghole et la Chine Qing , pour la soie, le coton, la porcelaine et les textiles. Ces produits étaient soit échangés en Asie contre les épices convoitées, soit ramenés en Europe. Le VOC a également joué un rôle déterminant dans l’introduction des idées et de la technologie européennes en Asie. L’entreprise a soutenu les missionnaires chrétiens et échangé des technologies modernes avec la Chine et le Japon. Un poste commercial de COV plus paisible sur Dejima , une île artificielle au large de Nagasaki, a été pendant plus de deux cents ans le seul endroit où les Européens étaient autorisés à commercer avec le Japon. [89] Lorsque le VOC a tenté d’utiliser la force militaire pour ouvrir la Chine de la dynastie Ming au commerce néerlandais, les Chinois ont vaincu les Néerlandais dans une guerre sur les îles Penghu de 1623 à 1624, forçant le VOC à abandonner Penghu pour Taiwan. Les Chinois ont de nouveau vaincu le VOC lors de la bataille de la baie de Liaoluo en 1633.

Les seigneurs vietnamiens Nguyen ont vaincu le VOC lors d’ une bataille de 1643 pendant la guerre Trịnh-Nguyễn , faisant exploser un navire néerlandais. Les Cambodgiens ont vaincu le VOC dans la guerre cambodgienne-néerlandaise de 1643 à 1644 sur le Mékong.

Établissement néerlandais au Bengale Subah .

Établissement néerlandais au Bengale Subah .

En 1640, la VOC obtient le port de Galle , Ceylan , des Portugais et brise le monopole de ces derniers sur le commerce de la cannelle . En 1658, Gérard Pietersz. Hulft a assiégé Colombo , qui a été capturé avec l’aide du roi Rajasinghe II de Kandy . En 1659, les Portugais avaient été expulsés des régions côtières, qui étaient alors occupées par le VOC, lui assurant le monopole de la cannelle. Pour empêcher les Portugais ou les Anglais de reprendre le Sri Lanka, le VOC a conquis toute la côte de Malabardes Portugais, les chassant presque entièrement de la côte ouest de l’Inde. Lorsque la nouvelle d’un accord de paix entre le Portugal et les Pays-Bas parvint en Asie en 1663, Goa était la seule ville portugaise restante sur la côte ouest. [90]

En 1652, Jan van Riebeeck a établi un avant-poste de réapprovisionnement au Cap des Tempêtes (la pointe sud-ouest de l’Afrique, aujourd’hui Cape Town , Afrique du Sud) pour desservir les navires de la compagnie lors de leur voyage vers et depuis l’Asie de l’Est. Le cap a ensuite été rebaptisé Cap de Bonne-Espérance en l’honneur de la présence de l’avant-poste. Bien que les navires n’appartenant pas à la compagnie soient les bienvenus pour utiliser la station, ils sont facturés de manière exorbitante. Ce poste devint plus tard une colonie à part entière, la colonie du Cap , lorsque davantage de Néerlandais et d’autres Européens commencèrent à s’y installer.

Au XVIIe siècle, des comptoirs commerciaux de COV ont également été établis en Perse , au Bengale , à Malacca , au Siam , à Formose (aujourd’hui Taiwan), ainsi que sur les côtes de Malabar et de Coromandel en Inde. L’accès direct à la Chine continentale est venu en 1729 lorsqu’une usine a été établie à Canton . [91] En 1662, cependant, Koxinga expulsa les Néerlandais de Taiwan [92] ( voir Histoire de Taiwan ).

En 1663, le VOC signa le “Traité de Painan” avec plusieurs seigneurs locaux de la région de Painan qui se révoltaient contre le Sultanat d’Aceh . Le traité a permis au VOC de construire un poste de traite dans la région et éventuellement d’y monopoliser le commerce, en particulier le commerce de l’or. [93]

En 1669, la VOC était la société privée la plus riche que le monde ait jamais vue, avec plus de 150 navires marchands, 40 navires de guerre, 50 000 employés, une armée privée de 10 000 soldats et un dividende de 40 % sur l’investissement initial. [94]

De nombreux employés de VOC se sont mélangés aux peuples autochtones et ont élargi la population d’ Indos dans l’histoire précoloniale . [95] [96]

Réorientation

Vers 1670, deux événements stoppent la croissance du commerce des COV. En premier lieu, le commerce très lucratif avec le Japon a commencé à décliner. La perte de l’avant-poste de Formose au profit de Koxinga lors du siège de Fort Zeelandia en 1662 et des troubles internes connexes en Chine (où la dynastie Ming était remplacée par la dynastie chinoise Qing ) a mis fin au commerce de la soie après 1666. Bien que le VOC ait remplacé Du Bengale moghol pour la soie chinoise, d’autres forces ont affecté l’approvisionnement en argent et en or japonais. Le shogunata adopté un certain nombre de mesures pour limiter l’exportation de ces métaux précieux, limitant ainsi les possibilités d’échange de COV et aggravant gravement les termes de l’échange. Par conséquent, le Japon a cessé de fonctionner comme la cheville ouvrière du commerce intra-asiatique des COV en 1685. [97]

Plus important encore, la troisième guerre anglo-néerlandaise a temporairement interrompu le commerce des COV avec l’Europe. Cela a provoqué une flambée du prix du poivre, ce qui a incité la Compagnie anglaise des Indes orientales (EIC) à entrer de manière agressive sur ce marché dans les années qui ont suivi 1672. Auparavant, l’un des principes de la politique de prix des COV était de sur-approvisionner légèrement le poivre. marché, de manière à faire baisser les prix en dessous du niveau auquel les intrus étaient encouragés à entrer sur le marché (au lieu de s’efforcer de maximiser les profits à court terme). La sagesse d’une telle politique s’est illustrée lorsqu’une féroce guerre des prix avec l’EIC s’est ensuivie, alors que cette société inondait le marché de nouveaux approvisionnements en provenance d’Inde. Dans cette lutte pour la part de marché, la VOC (qui disposait de ressources financières beaucoup plus importantes) pouvait attendre l’EIC. En effet, en 1683, ce dernier frôla la faillite ; le cours de son action a chuté de 600 à 250 ; et son président Josiah Child a été temporairement contraint de quitter ses fonctions. [98]

Cependant, l’écriture était sur le mur. D’autres compagnies, comme la Compagnie française des Indes orientales et la Compagnie danoise des Indes orientales ont également commencé à faire des percées dans le système néerlandais. Le VOC a donc fermé le grand magasin de poivre ouvert jusque-là florissant de Bantam par un traité de 1684 avec le sultan. Aussi, sur la côte de Coromandel , elle déplace son principal fief de Pulicat à Negapatnam , afin de s’assurer le monopole du commerce du poivre au détriment des Français et des Danois. [99]Cependant, l’importance de ces produits traditionnels dans le commerce Asie-Europe diminuait rapidement à l’époque. Les dépenses militaires que le VOC devait faire pour renforcer son monopole n’étaient pas justifiées par l’augmentation des profits de ce commerce en déclin. [100]

Néanmoins, cette leçon a été lente à s’imprégner et au début, le VOC a pris la décision stratégique d’améliorer sa position militaire sur la côte de Malabar (espérant ainsi réduire l’influence anglaise dans la région et mettre fin à la ponction sur ses ressources du coût de la Garnisons Malabar) en utilisant la force pour contraindre le Zamorin de Calicutse soumettre à la domination hollandaise. En 1710, le Zamorin fut contraint de signer un traité avec le VOC s’engageant à commercer exclusivement avec le VOC et à expulser les autres commerçants européens. Pendant une brève période, cela a semblé améliorer les perspectives de l’entreprise. Cependant, en 1715, avec les encouragements de l’EIC, les Zamorin renoncèrent au traité. Bien qu’une armée hollandaise ait réussi à réprimer temporairement cette insurrection, les Zamorin ont continué à commercer avec les Anglais et les Français, ce qui a entraîné une augmentation sensible du trafic anglais et français. La VOC décida en 1721 qu’il ne valait plus la peine d’essayer de dominer le commerce du poivre et des épices de Malabar . Une décision stratégique a été prise pour réduire la présence militaire néerlandaise et en fait céder la zone à l’influence de l’EIC. [101]

La bataille de Colachel en 1741 par les guerriers de Travancore sous Raja Marthanda Varma a vaincu les Néerlandais. Le commandant néerlandais, le capitaine Eustachius De Lannoy , est capturé. Marthanda Varma a accepté d’épargner la vie du capitaine néerlandais à condition qu’il rejoigne son armée et entraîne ses soldats sur des lignes modernes. Cette défaite dans la guerre Travancore-Hollandaise est considérée comme le premier exemple d’une puissance asiatique organisée surmontant la technologie et les tactiques militaires européennes; et cela a signalé le déclin de la puissance néerlandaise en Inde. [102]

La tentative de continuer comme avant en tant qu’entreprise commerciale à faible volume et à haut profit avec son activité principale dans le commerce des épices avait donc échoué. L’entreprise avait cependant déjà (à contrecœur) suivi l’exemple de ses concurrents européens en se diversifiant dans d’autres produits asiatiques, comme le thé, le café, le coton, les textiles et le sucre. Ces produits offraient une marge bénéficiaire plus faible et nécessitaient donc un volume de ventes plus important pour générer le même montant de revenus. Ce changement structurel dans la composition des produits de base du commerce des COV a commencé au début des années 1680, après que l’effondrement temporaire de l’EIC vers 1683 a offert une excellente opportunité d’entrer sur ces marchés. La cause réelle du changement réside cependant dans deux caractéristiques structurelles de cette nouvelle ère.

En premier lieu, il y a eu un changement révolutionnaire dans les goûts affectant la demande européenne pour les textiles asiatiques, le café et le thé, au tournant du XVIIIe siècle. Deuxièmement, une nouvelle ère d’offre abondante de capitaux à des taux d’intérêt bas s’est soudainement ouverte à cette époque. Le deuxième facteur a permis à l’entreprise de financer facilement son expansion dans les nouveaux domaines du commerce. [103] Entre les années 1680 et 1720, la VOC a donc pu équiper et équiper une expansion appréciable de sa flotte, et acquérir une grande quantité de métaux précieux pour financer l’achat de grandes quantités de produits asiatiques, pour expédition vers l’Europe. L’effet global a été d’environ doubler la taille de l’entreprise. [104]

Le tonnage des navires de retour a augmenté de 125 % au cours de cette période. Cependant, les revenus de l’entreprise provenant de la vente de marchandises débarquées en Europe n’ont augmenté que de 78 %. Cela reflète le changement fondamental qui s’était produit dans la situation de la VOC : elle opérait désormais sur de nouveaux marchés pour des biens à demande élastique, sur lesquels elle devait concurrencer sur un pied d’égalité avec d’autres fournisseurs. Cela a fait de faibles marges bénéficiaires. [105]Malheureusement, les systèmes d’information métier de l’époque rendaient cela difficile à discerner pour les dirigeants de l’entreprise, ce qui peut expliquer en partie les erreurs qu’ils ont commises avec du recul. Ce manque d’information aurait pu être contrebalancé (comme à une époque antérieure dans l’histoire de la VOC) par le sens des affaires des administrateurs. Malheureusement, à cette époque, ceux-ci étaient presque exclusivement recrutés dans la classe politique des régents , qui avait depuis longtemps perdu ses relations étroites avec les cercles marchands. [106]

Les faibles marges bénéficiaires n’expliquent pas à elles seules la détérioration des revenus. Dans une large mesure, les coûts de fonctionnement du VOC avaient un caractère “fixe” (établissements militaires, entretien de la flotte, etc.). Les niveaux de profit auraient donc pu être maintenus si l’augmentation de l’échelle des opérations commerciales qui avait effectivement eu lieu avait entraîné des économies d’échelle . Cependant, bien que de plus grands navires aient transporté le volume croissant de marchandises, la productivité du travail n’a pas suffisamment augmenté pour les réaliser. En général, les frais généraux de l’entreprise ont augmenté au rythme de la croissance du volume des échanges; la baisse des marges brutes s’est directement traduite par une baisse de la rentabilité du capital investi. L’ère de l’expansion a été celle de la “croissance sans profit”. [107]

Plus précisément: «[l] e bénéfice annuel moyen à long terme de« l’âge d’or »de la VOC de 1630 à 1670 était de 2,1 millions de florins, dont un peu moins de la moitié était distribuée sous forme de dividendes et le reste réinvesti. Le bénéfice annuel moyen à long terme dans “l’âge d’expansion” (1680-1730) était de 2,0 millions de florins, dont les trois quarts étaient distribués sous forme de dividendes et un quart réinvestis. Au cours de la période précédente, les bénéfices représentaient en moyenne 18 % du total des revenus ; au cours de la dernière période, 10 % . Le rendement annuel du capital investi au cours de la période précédente s’élevait à environ 6 % ; au cours de la dernière période, à 3,4 %. ” [107]

Néanmoins, aux yeux des investisseurs, la VOC ne s’en est pas trop mal tirée. Le cours de l’action a constamment oscillé autour de la barre des 400 à partir du milieu des années 1680 (à l’exception d’un contretemps autour de la Glorieuse Révolution en 1688), et il a atteint un sommet historique d’environ 642 dans les années 1720. Les actions VOC ont alors rapporté un rendement de 3,5 %, à peine inférieur au rendement des obligations d’État néerlandaises. [108]

Déclin et chute

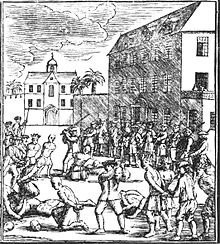

Une impression du massacre de Batavia en 1740

Une impression du massacre de Batavia en 1740

La maison Oost-Indisch ( Reinier Vinkeles , 1768)

La maison Oost-Indisch ( Reinier Vinkeles , 1768)

| Apprendre encore plus Cette section a besoin de citations supplémentaires pour vérification . ( mars 2017 ) Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Après 1730, la fortune de la VOC a commencé à décliner. Cinq problèmes majeurs, pas tous de poids égal, expliquent son déclin au cours des cinquante années suivantes jusqu’en 1780 : [109]

- Il y avait une érosion constante du commerce intra-asiatique en raison des changements de l’environnement politique et économique asiatique contre lesquels le VOC ne pouvait pas faire grand-chose. Ces facteurs ont progressivement évincé l’entreprise de la Perse, de Suratte , de la côte de Malabar et du Bengale. L’entreprise devait confiner ses opérations à la ceinture qu’elle contrôlait physiquement, de Ceylan à l’archipel indonésien. Le volume de ce commerce intra-asiatique, et sa rentabilité, ont donc dû se contracter.

- L’organisation de l’entreprise en Asie (centralisée sur son hub de Batavia), qui offrait initialement des avantages dans la collecte d’informations sur le marché, a commencé à causer des inconvénients au XVIIIe siècle en raison de l’inefficacité de tout expédier d’abord vers ce point central. Ce désavantage se faisait le plus sentir dans le commerce du thé, où des concurrents comme l’EIC et la société d’Ostende expédiaient directement de la Chine vers l’Europe.

- La «vénalité» du personnel du VOC (au sens de corruption et d’inexécution des tâches), bien qu’un problème pour toutes les compagnies des Indes orientales à l’époque, semble avoir tourmenté le VOC à plus grande échelle que ses concurrents. Certes, l’entreprise n’était pas un “bon employeur”. Les salaires étaient bas et le “commerce pour compte privé” n’était officiellement pas autorisé. Sans surprise, elle proliférera au XVIIIe siècle au détriment des performances de l’entreprise. [110] À partir des années 1790 environ, l’expression péri sous la corruption ( vergaan onder corruptie , également abrégé VOC en néerlandais) est venue résumer l’avenir de l’entreprise.

- Un problème que le VOC partageait avec d’autres entreprises était les taux élevés de mortalité et de morbidité parmi ses employés. Cela a décimé les rangs de l’entreprise et énervé de nombreux survivants.

- Une blessure auto-infligée était la politique de dividende du VOC . Les dividendes distribués par la société avaient dépassé le surplus qu’elle avait engrangé en Europe à chaque décennie de 1690 à 1760 sauf 1710-1720. Cependant, jusqu’en 1730, les administrateurs ont expédié des ressources en Asie pour y constituer le capital commercial. Une comptabilité consolidée aurait donc probablement montré que les bénéfices totaux dépassaient les dividendes. De plus, entre 1700 et 1740, la société a remboursé 5,4 millions de florins de dette à long terme. L’entreprise était donc encore sur une base financière solide au cours de ces années. Cela a changé après 1730. Alors que les bénéfices ont chuté, les bewindhebbersn’a que légèrement diminué les dividendes par rapport au niveau précédent. Les dividendes distribués étaient donc supérieurs aux revenus dans toutes les décennies sauf une (1760-1770). Pour ce faire, le stock de capital asiatique a dû être réduit de 4 millions de florins entre 1730 et 1780, et le capital liquide disponible en Europe a été réduit de 20 millions de florins au cours de la même période. Les dirigeants ont donc été contraints de reconstituer les liquidités de l’entreprise en recourant à des financements à court terme par emprunts anticipés, adossés aux revenus attendus des flottes domiciliées. [ citation nécessaire ]

Malgré ces problèmes, la VOC en 1780 resta une énorme opération. Son capital dans la République, composé de navires et de marchandises en inventaire, s’élevait à 28 millions de florins ; son capital en Asie, composé du fonds de commerce liquide et des marchandises en route vers l’Europe, s’élevait à 46 millions de florins. Le capital total, net de l’encours de la dette, s’élevait à 62 millions de florins. Les perspectives de l’entreprise à cette époque n’étaient donc pas sans espoir si l’un des plans de réforme avait été mené à bien. Cependant, la quatrième guerre anglo-néerlandaiseest intervenu. Les attaques navales britanniques en Europe et en Asie ont réduit de moitié la flotte VOC; a retiré une cargaison de valeur de son contrôle ; et a érodé son pouvoir restant en Asie. Les pertes directes de COV pendant la guerre peuvent être estimées à 43 millions de florins. Les prêts pour maintenir l’entreprise en activité ont réduit son actif net à zéro. [111]

À partir de 1720, le marché du sucre indonésien décline alors que la concurrence du sucre bon marché du Brésil augmente. Les marchés européens sont devenus saturés. Des dizaines de commerçants de sucre chinois ont fait faillite, ce qui a entraîné un chômage massif, qui à son tour a conduit à des gangs de coolies au chômage . Le gouvernement néerlandais de Batavia n’a pas répondu de manière adéquate à ces problèmes. En 1740, des rumeurs de déportation des gangs de la région de Batavia ont conduit à des émeutes généralisées. L’armée néerlandaise a fouillé les maisons des Chinois à Batavia à la recherche d’armes. Lorsqu’une maison a accidentellement brûlé, des militaires et des citoyens pauvres ont commencé à massacrer et à piller la communauté chinoise. [112] Ce massacre des Chinoisa été jugée suffisamment grave pour que le conseil d’administration du VOC ouvre une enquête officielle sur le gouvernement des Indes orientales néerlandaises pour la première fois de son histoire.

Après la quatrième guerre anglo-néerlandaise, le VOC était une épave financière. Après de vaines tentatives de réorganisation par les États provinciaux de Hollande et de Zélande, elle est nationalisée par la nouvelle République batave le 1er mars 1796. [113] La charte VOC est renouvelée plusieurs fois, mais peut expirer le 31 décembre 1799. [113] ] La plupart des possessions de l’ancien VOC ont ensuite été occupées par la Grande-Bretagne pendant les guerres napoléoniennes , mais après la création du nouveau Royaume-Uni des Pays-Bas par le Congrès de Vienne , certaines d’entre elles ont été restituées à cet État successeur de la République néerlandaise. par le traité anglo-néerlandais de 1814 .

Structure organisationnelle

La VOC a été l’un des premiers modèles pionniers de la société multinationale/transnationale, dans son sens moderne, à l’aube du capitalisme moderne.

Gravure du XVIIe siècle de la Oost-Indisch Huis (East India House), siège mondial du VOC.

Gravure du XVIIe siècle de la Oost-Indisch Huis (East India House), siège mondial du VOC.

C’est à Batavia (aujourd’hui Jakarta ) sur l’île de Java que la VOC établit son centre administratif , en tant que deuxième siège, avec un gouverneur général en charge à partir de 1610. L’entreprise avait également d’ importantes opérations ailleurs .

C’est à Batavia (aujourd’hui Jakarta ) sur l’île de Java que la VOC établit son centre administratif , en tant que deuxième siège, avec un gouverneur général en charge à partir de 1610. L’entreprise avait également d’ importantes opérations ailleurs .

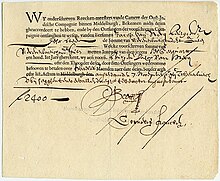

Une obligation de la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (VOC), datant du 7 novembre 1623. La VOC a été la première société de l’histoire à émettre des obligations et des actions au grand public. C’est le VOC qui a inventé l’idée d’investir dans l’entreprise plutôt que dans une entreprise spécifique régie par l’entreprise. La VOC a également été la première entreprise à utiliser un marché des capitaux à part entière (y compris le marché obligataire et le marché boursier ) comme canal crucial pour lever des fonds à moyen et long terme.

Une obligation de la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (VOC), datant du 7 novembre 1623. La VOC a été la première société de l’histoire à émettre des obligations et des actions au grand public. C’est le VOC qui a inventé l’idée d’investir dans l’entreprise plutôt que dans une entreprise spécifique régie par l’entreprise. La VOC a également été la première entreprise à utiliser un marché des capitaux à part entière (y compris le marché obligataire et le marché boursier ) comme canal crucial pour lever des fonds à moyen et long terme.

La VOC est généralement considérée comme la première véritable société transnationale au monde et elle a également été la première entreprise multinationale à émettre des actions au public. Certains historiens tels que Timothy Brook et Russell Shorto considèrent la VOC comme la société pionnière de la première vague de l’ ère de la mondialisation des entreprises . [39] [40] La VOC a été la première société multinationale à opérer officiellement sur différents continents tels que l’Europe, l’Asie et l’Afrique. Alors que le VOC opérait principalement dans ce qui deviendra plus tard les Indes orientales néerlandaises(Indonésie moderne), la société avait également d’importantes opérations ailleurs. Elle employait des personnes de continents et d’origines différents dans les mêmes fonctions et environnements de travail. Bien qu’il s’agisse d’une entreprise néerlandaise, ses employés comprenaient non seulement des Néerlandais, mais aussi de nombreux Allemands et d’autres pays. Outre la main- d’œuvre diversifiée du nord-ouest de l’Europe recrutée par le VOC en République néerlandaise , le VOC a largement utilisé les marchés du travail asiatiques locaux. En conséquence, le personnel des différents bureaux VOC en Asie était composé d’employés européens et asiatiques. Les travailleurs asiatiques ou eurasiens peuvent être employés comme marins, soldats, écrivains, charpentiers, forgerons ou comme simples ouvriers non qualifiés. [114]Au plus fort de son existence, la VOC comptait 25 000 employés qui travaillaient en Asie et 11 000 qui étaient en route. [115] De plus, alors que la plupart de ses actionnaires étaient néerlandais, environ un quart des premiers actionnaires étaient des Zuid-Nederlanders (personnes d’une région qui comprend la Belgique et le Luxembourg modernes ) et il y avait aussi quelques dizaines d’Allemands. [116]

La VOC avait deux types d’actionnaires : les participanten , qui pouvaient être considérés comme des membres non dirigeants, et les 76 bewindhebbers (réduits plus tard à 60) qui agissaient en tant que directeurs généraux. C’était la configuration habituelle des sociétés par actions néerlandaises à l’époque. L’innovation dans le cas de la VOC était que la responsabilité non seulement des participants mais aussi des bewindhebbers était limitée au capital versé (généralement, les bewindhebbers avaient une responsabilité illimitée). La VOC était donc une société à responsabilité limitée . De plus, le capital serait permanentpendant la durée de vie de l’entreprise. En conséquence, les investisseurs qui souhaitaient liquider leur participation dans l’intervalle ne pouvaient le faire qu’en vendant leur part à d’autres à la Bourse d’Amsterdam . [117] Confusion des confusions , un dialogue de 1688 du juif séfarade Joseph de la Vega analysait le fonctionnement de cette bourse unique.

Le VOC était composé de six chambres ( Kamers ) dans les villes portuaires : Amsterdam , Delft , Rotterdam , Enkhuizen , Middelburg et Hoorn . Les délégués de ces chambres se sont réunis sous le nom de Heeren XVII (les Lords Seventeen). Ils ont été sélectionnés parmi la classe d’actionnaires bewindhebber . [118]

Du Heeren XVII , huit délégués provenaient de la Chambre d’Amsterdam (un de moins qu’une majorité à lui seul), quatre de la Chambre de Zélande et un de chacune des petites Chambres, tandis que le dix-septième siège était alternativement de la Chambre de Middelburg-Zeeland ou tourné entre les cinq petites chambres. Amsterdam avait ainsi la voix décisive. Les Zélandais, en particulier, avaient des doutes sur cet arrangement au début. La crainte n’était pas sans fondement, car en pratique, cela signifiait qu’Amsterdam stipulait ce qui s’était passé.

Les six chambres ont levé le capital de démarrage de la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales :

| Chambre | Capitale ( florins ) |

|---|---|

| Amsterdam | 3 679 915 |

| Middelbourg | 1 300 405 |

| Enkhuizen | 540 000 |

| Delft | 469 400 |

| Corne | 266 868 |

| Rotterdam | 173 000 |

| Total: | 6 424 588 |

La levée de capitaux à Rotterdam ne s’est pas déroulée sans heurts. Une partie considérable provenait des habitants de Dordrecht . Bien qu’elle n’ait pas levé autant de capitaux qu’Amsterdam ou Middelburg-Zélande, Enkhuizen avait la plus grande contribution au capital social de la VOC. Sous les 358 premiers actionnaires, il y avait beaucoup de petits entrepreneurs, qui ont osé prendre le risque . L’investissement minimum dans le VOC était de 3 000 florins, ce qui valorisait les actions de la société dans les limites des moyens de nombreux marchands. [119]

Divers uniformes de soldats VOC, v. 1783

Divers uniformes de soldats VOC, v. 1783

Parmi les premiers actionnaires de la VOC, les immigrants ont joué un rôle important. Parmi les 1 143 soumissionnaires se trouvaient 39 Allemands et pas moins de 301 des Pays-Bas du Sud (à peu près présents la Belgique et le Luxembourg, alors sous la domination des Habsbourg ), dont Isaac le Maire était le plus gros abonné avec 85 000 ƒ. La capitalisation totale de VOC était dix fois supérieure à celle de son rival britannique.

Les Heeren XVII (Lords Seventeen) se sont réunis alternativement six ans à Amsterdam et deux ans à Middelburg-Zeeland. Ils définissent la politique générale de la VOC et répartissent les tâches entre les Chambres. Les Chambres effectuent tous les travaux nécessaires, construisent leurs propres navires et entrepôts et font le commerce des marchandises. Le Heeren XVII a envoyé les capitaines des navires avec des instructions détaillées sur la route à suivre, les vents dominants, les courants, les hauts-fonds et les points de repère. Le VOC a également produit ses propres cartes .

Dans le contexte de la guerre hollandaise-portugaise, la société a établi son siège à Batavia, Java (aujourd’hui Jakarta , Indonésie ). D’ autres avant – postes coloniaux ont également été établis dans les Indes orientales , comme sur le îles Maluku , qui comprennent les îles Banda , où le VOC a maintenu de force un monopole sur la noix de muscade et le macis . Les méthodes utilisées pour maintenir le monopole impliquaient l’ extorsion et la répression violente de la population indigène, y compris le meurtre de masse . [120]De plus, les représentants des COV ont parfois utilisé la tactique consistant à brûler des arbres à épices pour forcer les populations indigènes à cultiver d’autres cultures, coupant ainsi artificiellement l’approvisionnement en épices comme la noix de muscade et les clous de girofle. [121]

Activisme actionnarial et enjeux de gouvernance

Les deux côtés d’un conduit , une pièce de monnaie frappée en 1735 par le VOC

Les deux côtés d’un conduit , une pièce de monnaie frappée en 1735 par le VOC

Les hommes d’affaires néerlandais du XVIIe siècle, en particulier les investisseurs de la VOC, ont peut-être été les premiers investisseurs enregistrés de l’histoire à se pencher sérieusement sur les problèmes de gouvernance d’entreprise . [122] [123] Isaac Le Maire , qui est connu comme le premier vendeur à découvert enregistré de l’histoire , était également un actionnaire important du VOC. En 1609, il se plaignit de la mauvaise gouvernance d’entreprise de la VOC. Le 24 janvier 1609, Le Maire dépose une pétition contre la VOC, marquant la première expression enregistrée d’ activisme actionnarial . Dans ce qui est le premier différend enregistré en matière de gouvernance d’entreprise, Le Maire a formellement accusé le conseil d’administration de la VOC (la Heeren XVII) de chercher à “retenir l’argent d’autrui plus longtemps ou de l’utiliser autrement que ce dernier ne le souhaite” et a demandé la liquidation de la COV conformément aux pratiques commerciales standard. [124] [125] [126] Initialement le plus grand actionnaire unique de la VOC et un bewindhebbersiégeant au conseil d’administration, Le Maire a apparemment tenté de détourner les bénéfices de l’entreprise à lui-même en entreprenant 14 expéditions sous ses propres comptes au lieu de ceux de la société. Étant donné que ses importantes participations n’étaient pas accompagnées d’un plus grand pouvoir de vote, Le Maire fut bientôt évincé par d’autres gouverneurs en 1605 pour détournement de fonds et fut contraint de signer un accord pour ne pas concurrencer le VOC. Ayant conservé des actions dans l’entreprise à la suite de cet incident, Le Maire deviendrait en 1609 l’auteur de ce qui est célébré comme “la première expression enregistrée de défense des intérêts des actionnaires dans une société cotée en bourse”. [127] [128] [129]

En 1622, la première révolte d’actionnaires enregistrée de l’histoire s’est également produite parmi les investisseurs de VOC qui se sont plaints que les livres de comptes de l’entreprise avaient été “enduits de bacon” afin qu’ils puissent être “mangés par des chiens”. Les investisseurs ont exigé un “reeckeninge”, un audit financier en bonne et due forme. [130] La campagne 1622 des actionnaires de la VOC est un témoignage de la genèse de la responsabilité sociale des entreprises (RSE) dans laquelle les actionnaires ont organisé des manifestations en distribuant des pamphlets et en se plaignant de l’enrichissement personnel et du secret de la direction.[131]

Principaux postes de traite, colonies et colonies

| Apprendre encore plus Cette section est sous forme de liste mais peut mieux se lire en prose . ( février 2018 ) You can help by converting this section, if appropriate. Editing help is available. |

L’Europe

Pays-Bas

- Amsterdam (siège mondial)

- Delft

- Enkhuizen

- Corne

- Middelbourg

- Rotterdam

Afrique

Maurice

- Maurice néerlandais (1638–1658; 1664–1710)

Afrique du Sud

- Colonie néerlandaise du Cap (1652–1806)

Asie

Maquette du poste de traite néerlandais exposée à Dejima , Nagasaki (1995)

Maquette du poste de traite néerlandais exposée à Dejima , Nagasaki (1995)

Plan au sol du poste commercial néerlandais sur l’île Dejima à Nagasaki . Une vue à vol d’oiseau imaginaire de la disposition et des structures de Dejima (copiée à partir d’une gravure sur bois de Toshimaya Bunjiemon de 1780).

Plan au sol du poste commercial néerlandais sur l’île Dejima à Nagasaki . Une vue à vol d’oiseau imaginaire de la disposition et des structures de Dejima (copiée à partir d’une gravure sur bois de Toshimaya Bunjiemon de 1780).

Vue d’ensemble du Fort Zeelandia (Fort Anping) à Tainan , Taïwan, peint vers 1635 ( Bureau national des archives , La Haye )

Vue d’ensemble du Fort Zeelandia (Fort Anping) à Tainan , Taïwan, peint vers 1635 ( Bureau national des archives , La Haye )

La place hollandaise à Malacca , avec Christ Church (au centre) et le Stadthuys (à droite)

La place hollandaise à Malacca , avec Christ Church (au centre) et le Stadthuys (à droite)

- Batavia, Indes néerlandaises

sous-continent indien

- Coromandel néerlandais (1608–1825)

- Surate néerlandaise (1616–1825)

- Bengale néerlandais (1627–1825)

- Ceylan néerlandais (1640–1796)

- Malabar néerlandais (1661–1795)

Japon

- Hirado, Nagasaki (1609–1641)

- Dejima , Nagasaki (1641–1853)

Taïwan

- Anping ( Fort Zeelandia )

- Tainan ( Fort Province )

- Wang-an, Penghu , Îles Pescadores (Fort Vlissingen; 1620–1624)

- Keelung ( Fort Noord-Holland , Fort Victoria)

- Tamsui ( Fort Antonio )

Malaisie

- Malacca néerlandaise (1641–1795; 1818–1825)

Thaïlande

- Ayuthaya (1608–1767)

Viêt Nam

- Thǎng Long / Tonkin (1636–1699)

- Hội An (1636–1741)

Conflits et guerres impliquant le COV

| Apprendre encore plus Cette section a besoin d’être agrandie . Vous pouvez aider en y ajoutant . ( juillet 2018 ) |

L’histoire du conflit commercial VOC, par exemple avec la British East India Company (EIC), était parfois étroitement liée aux conflits militaires néerlandais. Les intérêts commerciaux du COV (et plus généralement des Pays-Bas) se reflétaient dans les objectifs militaires et les colonies convenues par traité. Dans le traité de Breda (1667) mettant fin à la seconde guerre anglo-néerlandaise , les Néerlandais ont finalement pu obtenir un monopole des COV pour le commerce de la noix de muscade , cédant l’île de Manhattan aux Britanniques tout en obtenant la dernière source de noix de muscade non contrôlée par les COV, l’île de Rhun dans les îles Banda . [132] Les Néerlandais ont ensuite repris Manhattan, mais le rendit avec la colonie de New Netherland dans le traité de Westminster (1674) mettant fin à la troisième guerre anglo-néerlandaise . Les Britanniques ont également renoncé à leurs revendications sur le Suriname dans le cadre du Traité de Westminster . Il y a également eu un effort pour compenser les pertes liées à la guerre de la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales au milieu du XVIIe siècle par les bénéfices de la VOC, bien que cela ait finalement été bloqué.

Rôles historiques et héritage

Une évolution de 400 ans des marchés boursiers mondiaux (et des marchés de capitaux en général)

Cour de la Bourse d’Amsterdam (ou Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser en néerlandais), la première bourse officielle au monde . Le marché boursier formel dans son sens moderne – en tant que l’un des mécanismes puissants du capitalisme moderne [133] [134] [135] – était une innovation pionnière des dirigeants et des actionnaires de la VOC au début du XVIIe siècle.

Cour de la Bourse d’Amsterdam (ou Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser en néerlandais), la première bourse officielle au monde . Le marché boursier formel dans son sens moderne – en tant que l’un des mécanismes puissants du capitalisme moderne [133] [134] [135] – était une innovation pionnière des dirigeants et des actionnaires de la VOC au début du XVIIe siècle.

La salle des marchés de la Bourse de New York (NYSE) au début du 21e siècle – comme l’un des principaux symboles du capitalisme américain à l’ère florissante d’Internet.

La salle des marchés de la Bourse de New York (NYSE) au début du 21e siècle – comme l’un des principaux symboles du capitalisme américain à l’ère florissante d’Internet.

L’un des plus anciens certificats d’actions connus , émis par la Chambre VOC d’ Enkhuizen , daté du 9 septembre 1606. [136] [137] [138] [139] La VOC a été la première société par actions enregistrée à obtenir un capital fixe . La VOC a également été la première société cotée en bourse à verser des dividendes réguliers . [140] Le VOC était peut-être en fait le tout premier titre de premier ordre . Dans Robert Shiller les mots de , le COVétait “la première véritable valeur importante” de l’histoire de la finance. [n]

L’un des plus anciens certificats d’actions connus , émis par la Chambre VOC d’ Enkhuizen , daté du 9 septembre 1606. [136] [137] [138] [139] La VOC a été la première société par actions enregistrée à obtenir un capital fixe . La VOC a également été la première société cotée en bourse à verser des dividendes réguliers . [140] Le VOC était peut-être en fait le tout premier titre de premier ordre . Dans Robert Shiller les mots de , le COVétait “la première véritable valeur importante” de l’histoire de la finance. [n]

La Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, ou VOC), fondée en 1602, a été la première société multinationale à responsabilité limitée au monde, ainsi que son premier cartel commercial soutenu par le gouvernement . Notre propre Compagnie des Indes orientales , fondée en 1600, est restée une clique de cafés jusqu’en 1657, date à laquelle elle a également commencé à vendre des actions, non pas dans des voyages individuels, mais dans la John Company elle-même, date à laquelle son rival néerlandais était de loin le plus grand. entreprise commerciale que le monde avait connue.

— Murray Sayle , London Review of Books , avril 2001 [49]

(…) Au fur et à mesure que les populations augmentaient, des infrastructures juridiques et financières plus solides ont commencé à se développer à travers l’Europe. Ces infrastructures, combinées aux progrès de la technologie maritime, ont rendu possible pour la première fois le commerce à grande échelle. En 1602, la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales est créée. C’était un nouveau type d’institution : la première entreprise multinationale et la première à émettre des actions publiques. Ces innovations ont permis à une seule entreprise de mobiliser des ressources financières auprès d’un grand nombre d’investisseurs et de créer des entreprises à une échelle qui n’était auparavant possible que pour les monarques .

— John Hagel et John Seely Brown , Deloitte Insights , mars 2013 [142]

En termes d’histoire commerciale mondiale, les leçons tirées des succès ou des échecs du VOC sont d’une importance cruciale. Dans son livre Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City (2013), l’auteur et historien américain Russell Shorto résume l’importance du VOC dans l’histoire du monde : “Comme les océans qu’il a maîtrisés, le VOC avait une portée difficile à comprendre. Un pourrait élaborer un argument défendable selon lequel aucune entreprise dans l’histoire n’a eu un tel impact sur le monde. Ses archives survivantes – à Cape Town , Colombo , Chennai , Jakarta , et La Haye– ont été mesurés (par un consortium sollicitant une subvention de l’UNESCO pour les préserver) en kilomètres. D’innombrables façons, la VOC a à la fois élargi le monde et réuni ses régions éloignées. Elle a introduit l’Europe en Asie et en Afrique, et inversement (tandis que sa multinationale sœur, la Compagnie des Indes occidentales , a mis New York en mouvement et colonisé le Brésil et les îles des Caraïbes). Il a été le pionnier de la mondialisation et a inventé ce qui pourrait être la première bureaucratie moderne. Il a fait progresser la cartographie et la construction navale. Il a favorisé la maladie, l’esclavage et l’exploitation à une échelle jamais vue auparavant.” [40]

Premier modèle pionnier de la société multinationale dans son sens moderne, [143] [144] [145] [146] la société est également considérée comme la première véritable société transnationale au monde . Au début des années 1600, la VOC est devenue la première société publique formellement cotée au monde, car elle a été la première société à être réellement cotée en bourse . Le VOC a eu une influence massive sur l’évolution de la société moderne en créant un prototype institutionnel pour les entreprises commerciales à grande échelle ultérieures .(en particulier les grandes entreprises comme les entreprises multinationales/transnationales/mondiales) et leur montée en puissance pour devenir une force socio-politico-économique très importante du monde moderne tel que nous le connaissons aujourd’hui. [147] [44] [148] [46] [149] [150] À bien des égards, les sociétés mondiales modernes cotées en bourse (y compris les sociétés Forbes Global 2000 ) [151] sont toutes des « descendants » d’un modèle commercial lancé par le COV au 17ème siècle. À l’instar des grandes entreprises modernes [152] , à bien des égards, la structure opérationnelle de la Compagnie anglaise / britannique des Indes orientales après 1657 était un dérivé du modèle VOC antérieur. [49] [50] [52][38] [53]

Au cours de son âge d’or, l’entreprise a joué un rôle crucial dans l’histoire maritime commerciale , financière, [o] socio-politico-économique, militaro-politique, diplomatique , ethnique et exploratoire du monde. Au début de la période moderne, le VOC était également le moteur de la montée de la mondialisation dirigée par les entreprises , [157] [2] le pouvoir des entreprises, l’identité d’ entreprise , la culture d’entreprise , la responsabilité sociale des entreprises , l’éthique d’entreprise, la gouvernance d’entreprise , la finance d’entreprise , capitalisme d’entreprise etcapitalisme financier . Avec ses innovations institutionnelles pionnières et ses rôles puissants dans l’histoire du monde, [158] l’entreprise est considérée par beaucoup comme la première grande, la première moderne, [p] [160] [161] [162] la première mondiale, la plus précieuse, [163 ] [164] et la société la plus influente jamais vue. [q] [39] [40] [41] Le VOC était aussi sans doute le premier modèle historique de la mégacorporation .

Innovations institutionnelles pionnières et impacts sur les pratiques commerciales mondiales modernes et le système financier

Une gravure du XVIIe siècle représentant la Bourse d’ Amsterdam (l’ancienne bourse d’Amsterdam , alias Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser en néerlandais), construite par Hendrick de Keyser (vers 1612). La Bourse d’Amsterdam (Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser), lancée par la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales au début des années 1600, a été la première bourse officielle (formelle) au monde lorsqu’elle a commencé à négocier les titres librement transférables du VOC, y compris les obligations et les actions . [165]

Une gravure du XVIIe siècle représentant la Bourse d’ Amsterdam (l’ancienne bourse d’Amsterdam , alias Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser en néerlandais), construite par Hendrick de Keyser (vers 1612). La Bourse d’Amsterdam (Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser), lancée par la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales au début des années 1600, a été la première bourse officielle (formelle) au monde lorsqu’elle a commencé à négocier les titres librement transférables du VOC, y compris les obligations et les actions . [165]

Cour de la Bourse d’Amsterdam ( Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser ) par Emanuel de Witte , 1653. Le processus d’achat et de vente des actions du VOC , à la Bourse d’Amsterdam, est devenu la base du premier marché boursier officiel (formel) , [166] [167] [168] une étape importante dans l’ histoire du capitalisme . [r]

Cour de la Bourse d’Amsterdam ( Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser ) par Emanuel de Witte , 1653. Le processus d’achat et de vente des actions du VOC , à la Bourse d’Amsterdam, est devenu la base du premier marché boursier officiel (formel) , [166] [167] [168] une étape importante dans l’ histoire du capitalisme . [r]

Foule rassemblée à Wall Street (New York) après le crash de 1929. Le krach de Wall Street de 1929 est souvent considéré comme l’un des pires krachs boursiers de l’histoire. Pour le meilleur ou pour le pire [38] , le système boursier quasi- casino créé par la VOC a profondément influencé l’évolution de l’économie mondiale depuis l’âge d’or néerlandais.

Foule rassemblée à Wall Street (New York) après le crash de 1929. Le krach de Wall Street de 1929 est souvent considéré comme l’un des pires krachs boursiers de l’histoire. Pour le meilleur ou pour le pire [38] , le système boursier quasi- casino créé par la VOC a profondément influencé l’évolution de l’économie mondiale depuis l’âge d’or néerlandais.

Les caractéristiques déterminantes de la société moderne, qui ont toutes émergé au cours du cycle néerlandais , comprennent : la responsabilité limitée pour les investisseurs, la libre transférabilité des intérêts des investisseurs, la personnalité juridique et la gestion centralisée. Bien que certaines de ces caractéristiques aient été présentes dans une certaine mesure dans les societas comperarum génoises du XIVe siècle du premier cycle , la première société publique à responsabilité limitée moderne entièrement connue était la VOC. Les structures organisationnelles et les pratiques d’entreprise de la VOC étaient étroitement parallèles à celles de la Compagnie anglaise des Indes orientales et ont servi de modèle direct à toutes les sociétés commerciales commerciales ultérieures de ladeuxième cycle , comprenant ceux de l’Italie, de la France , du Portugal, du Danemark et du Brandebourg-Prusse .

– Eric Michael Wilson, dans “La République sauvage” (2008) [169]

En 1602, des actions de la Dutch Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, mieux connue sous le nom de Dutch East India Company) ont été émises, créant soudainement ce qui est généralement considéré comme la première société cotée en bourse au monde . (…) Il existe d’autres prétendants au titre de première société publique, dont un moulin à eau du XIIe siècle en France et une société du XIIIe siècle destinée à contrôler le commerce de la laine anglaise, Staple of London. Ses actions, cependant, et la manière dont ces actions étaient négociées, ne permettaient pas vraiment la propriété publique par quiconque pouvait se permettre d’acheter une action. L’arrivée des actions VOC a donc été capitale, car comme Fernand Braudelsouligné, il a ouvert la propriété des entreprises et des idées qu’elles ont générées, au-delà des rangs de l’aristocratie et des très riches, afin que chacun puisse enfin participer à la liberté spéculative des transactions . En élargissant la propriété de son gâteau d’entreprise pour un certain prix et un rendement provisoire, les Néerlandais avaient fait quelque chose d’historique : ils avaient créé un marché des capitaux .

— Kevin Kaiser et David Young ( INSEAD ), dans « The Blue Line Imperative: What Managing for Value Really Means » (2013) [170]

Le COV a joué un rôle crucial dans la montée de la mondialisation dirigée par les entreprises , [171] la gouvernance d’entreprise , l’identité d’entreprise , [172] la responsabilité sociale des entreprises , la finance d’entreprise , l’ entrepreneuriat moderne et le capitalisme financier . [173] [174] [41] Au cours de son âge d’or, la société a fait quelques innovations institutionnelles fondamentales dans l’histoire économique et financière . Ces innovations financièrement révolutionnairesa permis à une seule entreprise (comme la VOC) de mobiliser des ressources financières auprès d’un grand nombre d’investisseurs et de créer des entreprises à une échelle qui n’était auparavant possible que pour les monarques. Selon l’historien et sinologue canadien Timothy Brook , « la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales – la VOC, comme on l’appelle – est au capitalisme d’entreprise ce que le cerf-volant de Benjamin Franklin est à l’électronique : le début de quelque chose d’important qui n’aurait pas pu être prédit à l’époque. le temps.” [39] La naissance et la croissance de la VOC (surtout au 17ème siècle) sont considérées par beaucoup comme le début officiel de l’ ère de la mondialisation des entreprises avec la montée des grandes entreprises.les entreprises commerciales (multinationales/transnationales en particulier) en tant que force socio-politico-économique extrêmement formidable [175] [176] [177] [39] qui affecte de manière significative la vie des gens aux quatre coins du monde aujourd’hui, [44] [45 ] [47] [178] [46] [179] [48] que ce soit pour le meilleur ou pour le pire. [30] En tant que première société cotée en bourse au monde et première société cotée (la première société à être cotée sur une bourse officielle), la VOC a été la première société à émettre des actions et des obligations .au grand public. Considérée par de nombreux experts comme la première véritable multinationale ( moderne) au monde [180] , la VOC a également été la première société par actions à responsabilité limitée à organisation permanente, dotée d’un capital permanent . [s] [182] Les actionnaires de VOC ont été les pionniers en jetant les bases d’une gouvernance d’entreprise et d’un financement d’ entreprise modernes . La VOC est souvent considérée comme le précurseur des entreprises modernes, sinon la première entreprise véritablement moderne. [183]C’est le VOC qui a inventé l’idée d’investir dans l’entreprise plutôt que dans une entreprise spécifique régie par l’entreprise. Avec ses caractéristiques pionnières telles que l’identité d’entreprise (premier logo d’entreprise mondialement reconnu ), l’esprit d’entreprise, la personnalité juridique , la structure opérationnelle transnationale (multinationale), la rentabilité élevée et stable, le capital permanent (capital fixe), [184] les actions librement transférables et négociables titres , séparation de la propriété et de la gestion, et responsabilité limitée pour les deux actionnaireset managers, la VOC est généralement considérée comme une percée institutionnelle majeure [185] et le modèle des grandes entreprises qui dominent désormais l’ économie mondiale . [186]

La place du Dam à Amsterdam, par Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde , ch. 1660. Dans l’image du centre d’Amsterdam très cosmopolite et tolérant, des personnalités musulmanes / orientales (peut-être des marchands ottomans ou marocains) sont représentées en train de négocier. Alors que le VOC était une force majeure derrière le miracle économique de la République néerlandaise au XVIIe siècle, les innovations institutionnelles du VOC ont joué un rôle décisif dans l’essor d’Amsterdam en tant que premier modèle moderne de centre financier international (mondial) .

La place du Dam à Amsterdam, par Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde , ch. 1660. Dans l’image du centre d’Amsterdam très cosmopolite et tolérant, des personnalités musulmanes / orientales (peut-être des marchands ottomans ou marocains) sont représentées en train de négocier. Alors que le VOC était une force majeure derrière le miracle économique de la République néerlandaise au XVIIe siècle, les innovations institutionnelles du VOC ont joué un rôle décisif dans l’essor d’Amsterdam en tant que premier modèle moderne de centre financier international (mondial) .

(…) Cette entreprise énigmatique [c’est-à-dire le fonctionnement interne de la bourse d’Amsterdam , principalement la pratique du VOC et du WICbourse] qui est à la fois la plus belle et la plus fourbe d’Europe, la plus noble et la plus infâme du monde, la plus belle et la plus vulgaire de la terre. C’est une quintessence de l’apprentissage académique et un parangon de la fraude ; c’est une pierre de touche pour les intelligents et une pierre tombale pour les audacieux, un trésor d’utilité et une source de désastre, (…) Le meilleur et le plus agréable aspect du nouveau commerce est qu’on peut s’enrichir sans risque. En effet, sans mettre en danger votre capital, et sans avoir rien à voir avec la correspondance, les avances d’argent, les entrepôts, les frais postaux, les caissiers, les sursis de paiement et autres incidents imprévus, vous avez la perspective de vous enrichir si, en cas de mauvais chance dans vos transactions, vous ne changerez que votre nom. Comme les Hébreux, lorsqu’ils sont gravement malades,

— Joseph de la Vega , dans son livre Confusión de confusiones (1688), le premier livre sur le commerce des actions [187]

La bourse – la série d’aventures diurnes des aisés – ne serait pas la bourse si elle n’avait pas ses hauts et ses bas. (…) Outre les avantages et les inconvénients économiques des bourses – l’avantage qu’elles offrent une libre circulation des capitaux pour financer l’expansion industrielle, par exemple, et l’inconvénient qu’elles offrent un moyen trop pratique pour les malchanceux, la imprudents et crédules à perdre leur argent – leur développement a créé tout un modèle de comportement social, avec des coutumes, un langage et des réponses prévisibles à des événements donnés. Ce qui est vraiment extraordinaire, c’est la rapidité avec laquelle ce modèle a émergé après la création, en 1611, de la première bourse importante du monde – une cour sans toit à Amsterdam .– et sa persistance (avec des variantes, il est vrai) à la Bourse de New York dans les années soixante. Le négoce d’actions actuel aux États-Unis – une entreprise incroyablement vaste, impliquant des millions de kilomètres de câbles télégraphiques privés, des ordinateurs capables de lire et de copier l’annuaire téléphonique de Manhattan en trois minutes et plus de vingt millions d’ actionnairesparticipants – semble bien loin d’une poignée de Hollandais du XVIIe siècle marchandant sous la pluie. Mais les marques de terrain sont sensiblement les mêmes. La première bourse a été, par inadvertance, un laboratoire dans lequel de nouvelles réactions humaines ont été révélées. De même, la Bourse de New York est aussi une éprouvette sociologique, contribuant à jamais à l’auto-compréhension de l’espèce humaine. Le comportement des pionniers de la négociation d’actions néerlandaises est bien documenté dans un livre intitulé « Confusion de confusions », écrit par un plongeur sur le marché d’Amsterdam nommé Joseph de la Vega ; initialement publié en 1688 (…)

– John Brooks , dans “Business Adventures” (1968) [188]

Les entreprises commerciales à actionnaires multiples sont devenues populaires avec les contrats de commenda dans l’Italie médiévale ( Greif , 2006, p. 286), et Malmendier (2009) fournit la preuve que les sociétés par actions remontent à la Rome antique . Pourtant, le titre de premier marché boursier du monde revient à juste titre à celui d’Amsterdam au XVIIe siècle, où un marché secondaire actif des actions de sociétés a émergé. Les deux principales sociétés étaient la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales et la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales , fondées en 1602 et 1621. D’autres sociétés existaient, mais elles n’étaient pas aussi importantes et constituaient une petite partie du marché boursier.

— Edward P. Stringham et Nicholas A. Curott, dans “The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics” [ On the Origins of Stock Markets ] (2015) [189]