Munich

Munich ( / ˈ m juː n ɪ k / MEW -nik ; Allemand : München [ˈmʏnçn̩] ( écouter )![]() ; Bavarois : Minga [ˈmɪŋ(ː)ɐ] ( écouter )

; Bavarois : Minga [ˈmɪŋ(ː)ɐ] ( écouter )![]() ) est la capitale et la ville la plus peuplée de l’ état allemand de Bavière . Avec une population de 1 558 395 habitants au 31 juillet 2020, [4] c’est la troisième plus grande ville d’Allemagne , après Berlin et Hambourg , et donc la plus grande qui ne constitue pas son propre État, ainsi que la 11e plus grande ville dans l’ Union européenne . La région métropolitaine de la ville abrite 6 millions de personnes. [5] A cheval sur les rives de l’ Isar (un affluent duDanube ) au nord des Alpes bavaroises , Munich est le siège de la région administrative bavaroise de Haute-Bavière , tout en étant la commune la plus densément peuplée d’Allemagne (4 500 habitants au km 2 ). Munich est la deuxième plus grande ville de la région dialectale bavaroise , après Vienne , la capitale autrichienne .

) est la capitale et la ville la plus peuplée de l’ état allemand de Bavière . Avec une population de 1 558 395 habitants au 31 juillet 2020, [4] c’est la troisième plus grande ville d’Allemagne , après Berlin et Hambourg , et donc la plus grande qui ne constitue pas son propre État, ainsi que la 11e plus grande ville dans l’ Union européenne . La région métropolitaine de la ville abrite 6 millions de personnes. [5] A cheval sur les rives de l’ Isar (un affluent duDanube ) au nord des Alpes bavaroises , Munich est le siège de la région administrative bavaroise de Haute-Bavière , tout en étant la commune la plus densément peuplée d’Allemagne (4 500 habitants au km 2 ). Munich est la deuxième plus grande ville de la région dialectale bavaroise , après Vienne , la capitale autrichienne .

| Munich München ( allemand ) Minga ( bavarois ) |

|

|---|---|

| Ville | |

De haut, de gauche à droite : De haut, de gauche à droite : Marienplatz avec Neues Rathaus et Frauenkirche en arrière-plan ; Palais de Nymphenburg ; jardin anglais ; BMW Welt ; Feldherrnhalle ; et Allianz Arena |

|

Drapeau Drapeau  Blason Blason |

|

Localisation de Munich  Wikimédia | © OpenStreetMap Wikimédia | © OpenStreetMap |

|

|

|

| Coordonnées : 48°08′15′′N 11°34′30′′E / 48.13750°N 11.57500°E / 48.13750; 11.57500Coordinates: 48°08′15′′N 11°34′30′′E / 48.13750°N 11.57500°E / 48.13750; 11.57500 | |

| Pays | Allemagne |

| État | Bavière |

| Admin. Région | Haute-Bavière |

| District | Quartier urbain |

| Mentionné pour la première fois | 1158 |

| Subdivisions | 25 arrondissements

|

| Gouvernement | |

| • Lord maire (2020–26) | Dieter Reiter [1] ( SPD ) |

| • Partis au pouvoir | Verts / SPD |

| Région | |

| • Ville | 310,71 km 2 (119,97 milles carrés) |

| Élévation | 520 m (1710 pieds) |

| Population (2020-12-31) [3] | |

| • Ville | 1 488 202 |

| • Densité | 4 800/km 2 (12 000/mi carré) |

| • Urbain | 2 606 021 |

| • Métro | 5 991 144 [2] |

| Fuseau horaire | UTC+01:00 ( CET ) |

| • Été ( DST ) | UTC+02:00 ( CEST ) |

| Codes postaux | 80331–81929 |

| Codes de numérotation | 089 |

| Immatriculation des véhicules | M |

| Site Internet | stadt.muenchen.de |

Mariensäule sur la Marienplatz

Mariensäule sur la Marienplatz  Vue aérienne

Vue aérienne

La ville a été mentionnée pour la première fois en 1158. Munich catholique a fortement résisté à la Réforme et a été un point de divergence politique pendant la guerre de Trente Ans qui en a résulté , mais est restée physiquement intacte malgré une occupation par les Suédois protestants . [6] Une fois que la Bavière a été établie comme un royaume souverain en 1806, Munich est devenu un centre européen important d’arts, d’architecture, de culture et de science. En 1918, pendant la Révolution allemande , la maison régnante de Wittelsbach , qui gouvernait la Bavière depuis 1180, fut contrainte d’abdiquer à Munich et une république socialiste de courte durée.a été déclaré. Dans les années 1920, Munich est devenue le siège de plusieurs factions politiques, dont le NSDAP . Après l’arrivée au pouvoir des nazis, Munich a été déclarée “capitale du mouvement”. La ville a été lourdement bombardée pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale , mais a restauré la plupart de son paysage urbain traditionnel. Après la fin de l’occupation américaine d’après-guerre en 1949, il y a eu une forte augmentation de la population et de la puissance économique pendant les années de Wirtschaftswunder , ou “miracle économique”. La ville a accueilli les Jeux olympiques d’été de 1972 et a été l’une des villes hôtes des Coupes du monde de football de 1974 et 2006 .

Aujourd’hui, Munich est un centre mondial d’ art , de science , de technologie , de finance , d’édition , de culture , d’innovation , d’éducation , d’affaires et de tourisme et jouit d’un niveau et d’une qualité de vie très élevés, atteignant le premier en Allemagne et le troisième dans le monde selon le 2018 Enquête Mercer , [7] et étant classée ville la plus vivable au monde par l’ enquête sur la qualité de vie de Monocle 2018 . [8]Munich est régulièrement classée comme l’une des villes les plus chères d’Allemagne en termes de prix de l’immobilier et de coûts de location. [9] [10] Selon l’ Institut de recherche sur la mondialisation et les classements mondiaux , Munich est considérée comme une Ville mondiale alpha , à partir de 2015 . [11] C’est l’une des villes les plus prospères [12] et à la croissance la plus rapide [13] d’Allemagne.[update]

L’économie de Munich est basée sur la haute technologie , l’ automobile , le Secteur des services et les industries créatives , ainsi que l’ informatique , la biotechnologie , l’ingénierie et l’électronique parmi de nombreux autres secteurs. Elle a l’économie la plus forte de toutes les villes allemandes et le taux de chômage le plus bas de toutes les villes d’Allemagne de plus d’un million d’habitants. Munich est également l’un des sites d’affaires les plus attractifs d’Allemagne. La ville abrite de nombreuses entreprises multinationales, telles que BMW , Siemens , MAN , Allianz et MunichRE. En outre, Munich abrite deux universités de recherche, une multitude d’institutions scientifiques et des musées technologiques et scientifiques de classe mondiale comme le Deutsches Museum et le BMW Museum . [14] Les nombreuses attractions architecturales et culturelles de Munich, les événements sportifs, les expositions et son Oktoberfest annuel , le plus grand Volksfest du monde , attirent un tourisme considérable . [15] La ville abrite plus de 530 000 personnes d’origine étrangère, soit 37,7 % de sa population. [16]

Histoire

Grandes armoiries de la ville de Munich 2:43 “Solang der alte Peter”, l’hymne de la ville de Munich

Grandes armoiries de la ville de Munich 2:43 “Solang der alte Peter”, l’hymne de la ville de Munich

Étymologie

Le nom de la ville est généralement interprété comme dérivant du terme ancien / moyen haut allemand Munichen , signifiant “par les moines”. Un moine est également représenté sur les armoiries de la ville .

La ville est mentionnée pour la première fois comme forum apud Munichen dans l ‘ arbitrage d’ Augsbourg [ de ] du 14 juin 1158 par l’ empereur romain germanique Frédéric Ier . [17] [18]

Le nom en allemand moderne est München , mais cela a été traduit de différentes manières dans différentes langues : en anglais , français , espagnol et diverses autres langues par “Munich”, en italien par “Monaco di Baviera”, en portugais par “Munique”. [19]

Préhistoire

Les découvertes archéologiques à Munich, comme à Freiham / Aubing, indiquent des premiers établissements et des tombes datant de l’ âge du bronze (7e-6e siècles avant JC). [20] [21] L’ évidence des règlements celtiques de l’ Âge de fer a été découverte dans les régions autour de Perlach . [22]

Période romaine

L’ancienne voie romaine Via Julia, qui reliait Augsbourg et Salzbourg, traversait la rivière Isar au sud de l’actuelle Munich, dans les villes de Baierbrunn et Gauting. [23] Une colonie romaine au nord-est du centre-ville de Munich a été fouillée dans le quartier de Denning/Bogenhausen. [24]

Colonies post-romaines

Au 6ème siècle et au-delà, divers groupes ethniques, tels que les Baiuvarii , ont peuplé la région autour de CE qui est aujourd’hui la Munich moderne, comme à Johanneskirchen, Feldmoching, Bogenhausen et Pasing. [25] [26] La première église chrétienne connue a été construite ca. 815 à Fröttmanning. [27]

Origine de la cité médiévale

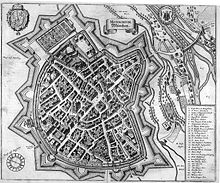

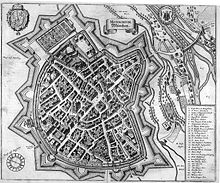

Munich au XVIe siècle

Munich au XVIe siècle

Plan de Munich en 1642

Plan de Munich en 1642

L’origine de la ville moderne de Munich est le résultat d’une lutte de pouvoir entre un chef de guerre militaire et un évêque catholique influent. Henri le Lion , duc de Saxe et duc de Bavière (mort en 1195) était l’un des princes allemands les plus puissants de son temps. Il a régné sur de vastes territoires du Saint Empire romain germanique , de la mer du Nord et de la Baltique aux Alpes. Henry voulait étendre son pouvoir en Bavière en prenant le contrôle du commerce lucratif du sel , que l’Église catholique de Freising avait sous son contrôle.

L’évêque Otto von Freising (mort en 1158) était un érudit, historien et évêque d’une grande partie de la Bavière qui faisait partie de son diocèse de Freising . Des années plus tôt (l’heure exacte n’est pas claire, mais peut-être au début du 10ème siècle), les moines bénédictins ont aidé à construire un pont à péage et un poste de douane sur la rivière Isar (probablement dans la ville moderne d’Oberföhring) pour contrôler le commerce du sel. entre Augsbourg et Salzbourg (qui existait depuis l’époque romaine ).

Henry voulait contrôler le pont à péage et ses revenus pour lui-même, alors il a détruit le pont et la douane en 1156. Il a ensuite construit un nouveau pont à péage, une douane et un marché aux pièces plus près de sa maison en aval (dans une colonie autour de la zone de la vieille ville moderne de Munich : Marienplatz, Marienhof et l’église Saint-Pierre). CE nouveau pont à péage a très probablement traversé l’Isar où se trouvent maintenant le Museuminsel et le Ludwigsbrücke moderne. [28]

L’évêque Otto a protesté auprès de son neveu, l’empereur Frederick Barbarosa (mort en 1190). Cependant, le 14 juin 1158, à Augsbourg, le conflit est réglé en faveur du duc Henri. L ‘ arbitrage d’ Augsbourg mentionne le nom du lieu litigieux comme forum apud Munichen . Bien que l’évêque Otto ait perdu son pont, les arbitres ont ordonné au duc Henri de verser un tiers de ses revenus à l’évêque de Freising à titre de compensation. [29] [30] [31]

Le 14 juin 1158 est considéré comme le «jour de fondation» officiel de la ville de Munich, et non la date à laquelle elle a été colonisée pour la première fois. Des fouilles archéologiques sur la place Marienhof (près de Marienplatz ) avant l’expansion du S-Bahn (métro) en 2012 ont découvert des éclats de navires du XIe siècle, CE qui prouve à nouveau que la colonie de Munich doit être antérieure à l’arbitrage d’Augsbourg de 1158. [32] [ 33] L’ancienne église Saint-Pierre près de la Marienplatz est également considérée comme antérieure à la date de fondation de la ville. [34]

En 1175, Munich reçut le statut de ville et de fortification. En 1180, après la disgrâCE d’Henri le Lion avec l’empereur Frédéric Barbarosa, y compris son procès et son exil, Otto Ier Wittelsbach devint duc de Bavière et Munich fut remis à l’ évêque de Freising . En 1240, Munich est transférée à Otto II Wittelsbach et en 1255, lorsque le duché de Bavière est scindé en deux, Munich devient la résidence ducale de Haute-Bavière .

Le duc Louis IV , originaire de Munich, est élu roi d’Allemagne en 1314 et couronné empereur du Saint Empire romain germanique en 1328. Il renforce la position de la ville en lui accordant le monopole du sel, lui assurant ainsi des revenus supplémentaires.

Le 13 février 1327, un grand incendie éclata à Munich qui dura deux jours et détruisit environ un tiers de la ville. [35]

En 1349, la peste noire ravage Munich et la Bavière. [36]

Au XVe siècle, Munich connaît un renouveau des arts gothiques : l’ancien hôtel de ville est agrandi et la plus grande église gothique de Munich – la Frauenkirche – aujourd’hui cathédrale, est construite en seulement 20 ans, à partir de 1468.

Capitale de la Bavière réunifiée

Marienplatz , Munich vers 1650

Marienplatz , Munich vers 1650

Bannières aux couleurs de Munich (à gauche) et de la Bavière (à droite) avec la Frauenkirche en arrière-plan

Bannières aux couleurs de Munich (à gauche) et de la Bavière (à droite) avec la Frauenkirche en arrière-plan

Lorsque la Bavière est réunie en 1506 après une brève guerre contre le duché de Landshut , Munich devient sa capitale. Les arts et la politique sont devenus de plus en plus influencés par la cour (voir Orlando di Lasso et Heinrich Schütz ). Au XVIe siècle, Munich était un centre de la contre-réforme allemande , ainsi que des arts de la Renaissance . Le duc Wilhelm V a commandé la Jésuite Michaelskirche , qui est devenue un centre de la contre-réforme, et a également construit la Hofbräuhaus pour le brassage de la bière brune en 1589. La Ligue catholique a été fondée à Munich en 1609.

En 1623, pendant la guerre de Trente Ans , Munich devient une résidence électorale lorsque Maximilien Ier, duc de Bavière est investi de la dignité électorale , mais en 1632 la ville est occupée par Gustav II Adolphe de Suède . Lorsque la peste bubonique éclata en 1634 et 1635, environ un tiers de la population mourut. Sous la régence des électeurs bavarois, Munich fut un centre important de la vie baroque , mais dut aussi subir les occupations des Habsbourg en 1704 et 1742.

Après avoir conclu une alliance avec la France napoléonienne, la ville est devenue la capitale du nouveau royaume de Bavière en 1806 avec l’électeur Maximilien Joseph devenant son premier roi. Le parlement de l’État (le Landtag ) et le nouvel archidiocèse de Munich et Freising étaient également situés dans la ville.

Du début au milieu du XIXe siècle, les anciens murs fortifiés de la ville de Munich ont été en grande partie démolis en raison de l’expansion démographique. [37]

Le festival annuel de la bière de Munich, l’ Oktoberfest , tire ses origines d’un mariage royal en octobre 1810. Les champs font maintenant partie de la « Theresienwiese » près du centre-ville.

En 1826, l’Université de Landshut a été transférée à Munich. Beaucoup des plus beaux bâtiments de la ville appartiennent à cette période et ont été construits sous les trois premiers rois bavarois. En particulier , Ludwig I a rendu des services exceptionnels au statut de Munich en tant que centre des arts, attirant de nombreux artistes et améliorant la substance architecturale de la ville avec de grands boulevards et des bâtiments.

La première gare de Munich a été construite en 1839, avec une ligne allant à Augsbourg à l’ouest. En 1849, une nouvelle gare centrale de Munich ( München Hauptbahnhof ) a été achevée, avec une ligne allant à Landshut et Ratisbonne au nord. [38] [39]

Au moment où Ludwig II devint roi en 1864, il resta principalement à l’écart de sa capitale et se concentra davantage sur ses châteaux fantaisistes dans la campagne bavaroise, c’est pourquoi il est connu dans le monde entier comme le «roi des contes de fées». Néanmoins, son patronage de Richard Wagner a assuré sa réputation posthume, tout comme ses châteaux, qui génèrent encore des revenus touristiques importants pour la Bavière. Plus tard, les années du prince régent Luitpold en tant que régent ont été marquées par une formidable activité artistique et culturelle à Munich, rehaussant son statut de force culturelle d’importance mondiale (voir Franz von Stuck et Der Blaue Reiter ).

Première Guerre mondiale à la Seconde Guerre mondiale

Troubles pendant le putsch de la brasserie

Troubles pendant le putsch de la brasserie

Après le déclenchement de la Première Guerre mondiale en 1914, la vie à Munich est devenue très difficile, car le blocus allié de l’Allemagne a entraîné des pénuries de nourriture et de carburant. Lors des raids aériens français en 1916, trois bombes tombent sur Munich.

En mars 1916, trois sociétés distinctes de moteurs d’avions et d’automobiles se sont associées pour former la « Bayerische Motoren Werke » ( BMW ) à Munich. [40]

Après la Première Guerre mondiale, la ville était au centre d’importants troubles politiques. En novembre 1918, à la veille de la révolution allemande, Ludwig III et sa famille fuient la ville. Après l’assassinat du premier premier ministre républicain de Bavière Kurt Eisner en février 1919 par Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley , la République soviétique bavaroise est proclamée. Lorsque les communistes ont pris le pouvoir, Lénine , qui avait vécu à Munich quelques années auparavant, a envoyé un télégramme de félicitations, mais la République soviétique a été supprimée le 3 mai 1919 par les Freikorps . Alors que le gouvernement républicain avait été rétabli, Munich devint un foyer de politique extrémiste, parmi lesquels Adolf Hitler et lesLes nationaux-socialistes ont rapidement pris de l’importance.

Dommages causés par les bombardements à l’Altstadt. Remarquez l’Altes Rathaus sans toit et grêlé qui regarde le Tal. La Heilig-Geist-Kirche sans toit se trouve à droite de la photo. Sa flèche, sans le sommet en cuivre, se trouve derrière l’église. La tour de la porte de Talbruck a complètement disparu.

Dommages causés par les bombardements à l’Altstadt. Remarquez l’Altes Rathaus sans toit et grêlé qui regarde le Tal. La Heilig-Geist-Kirche sans toit se trouve à droite de la photo. Sa flèche, sans le sommet en cuivre, se trouve derrière l’église. La tour de la porte de Talbruck a complètement disparu.

Le premier studio de cinéma de Munich ( Bavaria Film ) a été fondé en 1919. [41]

En 1923, Adolf Hitler et ses partisans, concentrés à Munich, organisent le putsch de la brasserie , une tentative de renverser la République de Weimar et de prendre le pouvoir. La révolte a échoué, entraînant l’arrestation d’Hitler et la paralysie temporaire du parti nazi (NSDAP). La ville redevint importante pour les nazis lorsqu’ils prirent le pouvoir en Allemagne en 1933. Le parti créa son premier camp de concentration à Dachau , à 16 km (9,9 mi) au nord-ouest de la ville. En raison de son importance pour la montée du national-socialisme, Munich était surnommée la Hauptstadt der Bewegung (“Capitale du mouvement”). [42] Le siège du NSDAP était à Munich et de nombreuxDes Führerbauten (” bâtiments du Führer “) ont été construits autour de la Königsplatz , dont certains survivent encore.

En mars 1924, Munich diffuse sa première émission de radio. La station devient ‘ Bayerischer Rundfunk ‘ en 1931. [43]

La ville a été le site où les accords de Munich de 1938 ont été signés entre la Grande- Bretagne et la France avec l’Allemagne dans le cadre de la politique franco-britannique d’ apaisement . Le Premier ministre britannique Neville Chamberlain a donné son assentiment à l’annexion allemande de la région des Sudètes de la Tchécoslovaquie dans l’espoir de satisfaire l’expansion territoriale d’Hitler. [44]

Le premier aéroport de Munich a été achevé en octobre 1939, dans la région de Riem. L’aéroport y restera jusqu’à CE qu’il soit rapproché de Freising en 1992. [45]

Le 8 novembre 1939, peu de temps après le début de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, une bombe a été posée dans le Bürgerbräukeller à Munich dans le but d’assassiner Adolf Hitler lors d’un discours d’un parti politique. Hitler, cependant, avait quitté le bâtiment quelques minutes avant l’explosion de la bombe. Sur son site se dressent aujourd’hui le bâtiment GEMA , le centre culturel Gasteig et le Munich City Hilton Hotel. [46]

Munich était la base de la Rose blanche , un mouvement de résistance étudiant de juin 1942 à février 1943. Les principaux membres ont été arrêtés et exécutés suite à une distribution de tracts à l’université de Munich par Hans et Sophie Scholl.

La ville a été lourdement endommagée par les bombardements alliés pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale , avec 71 raids aériens sur cinq ans. Les troupes américaines ont libéré Munich le 30 avril 1945. [47]

Après la guerre

Après l’occupation américaine en 1945, Munich a été entièrement reconstruite selon un plan minutieux, qui a conservé son quadrillage d’avant-guerre. En 1957, la population de Munich dépassait le million. La ville a continué à jouer un rôle très important dans l’économie, la politique et la culture allemandes, donnant lieu à son surnom de Heimliche Hauptstadt (“capitale secrète”) dans les décennies qui ont suivi la Seconde Guerre mondiale. [48]

À Munich, Bayerischer Rundfunk a lancé sa première émission télévisée en 1954. [49]

Depuis 1963, Munich est la ville hôte des conférences annuelles sur la politique de sécurité internationale .

Munich s’est également fait connaître sur le plan politique grâCE à la forte influence de l’homme politique bavarois Franz Josef Strauss des années 1960 aux années 1980. L’aéroport de Munich (construit en 1992) a été nommé en son honneur. [50]

Munich a été le site des Jeux olympiques d’été de 1972 , au cours desquels 11 athlètes israéliens ont été assassinés par des terroristes palestiniens lors du massacre de Munich , lorsque des hommes armés du groupe palestinien ” Septembre noir ” ont pris en otage des membres de l’équipe olympique israélienne. [ citation nécessaire ] Des meurtres de masse ont également eu lieu à Munich en 1980 et 2016 .

Munich a également accueilli la finale de la Coupe du monde de football en 1974.

Munich accueille également le célèbre festival de la bière forte de Nockherberg pendant la période de jeûne du carême (généralement en mars). Ses origines remontent au 17e/18e siècle, mais sont devenues populaires lorsque les festivités ont été télévisées pour la première fois dans les années 1980. Le festival comprend des discours comiques et une mini-comédie musicale dans laquelle de nombreux politiciens allemands sont parodiés par des acteurs sosies. [51]

Munich a été l’une des villes hôtes de la Coupe du monde de football 2006 .

Munich était l’une des villes hôtes du championnat d’Europe de football/football de l’UEFA 2020 (qui a été retardé d’un an en raison de la pandémie de COVID-19 en Allemagne ).

Géographie

Photo satellite de Munich par ESA Sentinel-2

Photo satellite de Munich par ESA Sentinel-2

Topographie

Munich se trouve sur les plaines élevées de la Haute-Bavière , à environ 50 km (31 mi) au nord de l’extrémité nord des Alpes , à une altitude d’environ 520 m (1 706 pieds) ASL . Les rivières locales sont l’ Isar et le Würm . Munich est située dans l’avant-pays alpin du nord . La partie nord de CE plateau sableux comprend une zone de silex très fertile qui n’est plus affectée par les processus de plissement rencontrés dans les Alpes, tandis que la partie sud est couverte de collines morainiques . Entre ceux-ci se trouvent des champs d’ épandage fluvio-glaciaire , comme autour de Munich. Partout où ces dépôts s’amincissent, lales eaux souterraines peuvent imprégner la surface de gravier et inonder la zone, conduisant à des marais comme dans le nord de Munich.

Climat

Selon les modèles de classification de Köppen et les données mises à jour, le climat est océanique ( Cfb ), indépendant de l’isotherme mais avec quelques caractéristiques continentales humides ( Dfb ) comme des étés chauds à chauds et des hivers froids, mais sans couverture de neige permanente. [52] [53] La proximité des Alpes apporte des volumes plus élevés de précipitations et par conséquent une plus grande susceptibilité aux problèmes d’inondation . Des études d’ adaptation au changement climatique et aux événements extrêmes sont menées, l’une d’entre elles est le Plan Isar de l’ UE Adaptation Climat. [54]

Le centre-ville se situe entre les deux climats, tandis que l’ aéroport de Munich a un climat continental humide . Le mois le plus chaud, en moyenne, est juillet. Le mois de janvier est le plus frais.

Les averses et les orages apportent les précipitations mensuelles moyennes les plus élevées à la fin du printemps et tout au long de l’été. Le plus de précipitations se produit en juillet, en moyenne. L’hiver a tendance à avoir moins de précipitations, le moins en février.

L’altitude plus élevée et la proximité des Alpes font que la ville a plus de pluie et de neige que de nombreuses autres régions d’Allemagne. Les Alpes affectent également le climat de la ville d’autres manières ; par exemple, le vent chaud descendant des Alpes ( vent föhn ), qui peut augmenter fortement les températures en quelques heures, même en hiver.

Étant au centre de l’Europe, Munich est soumise à de nombreuses influences climatiques, de sorte que les conditions météorologiques y sont plus variables que dans d’autres villes européennes, en particulier celles situées plus à l’ouest et au sud des Alpes.

Aux stations météorologiques officielles de Munich, les températures les plus élevées et les plus basses jamais mesurées sont de 37,5 °C (100 °F), le 27 juillet 1983 à Trudering-Riem, et de −31,6 °C (−24,9 °F), le 12 février 1929 à Botanic Jardin de la ville. [55] [56]

| Données climatiques pour Munich (Dreimühlenviertel), altitude : 515 m et 535 m, normales de 1981 à 2010, extrêmes de 1954 à aujourd’hui [a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | Fév | Mar | Avr | Mai | Juin | Juil | Août | Sep | Oct | Nov | Déc | An |

| Record élevé en °C (°F) | 18,9 (66,0) |

21,4 (70,5) |

24,0 (75,2) |

32,2 (90,0) |

31,8 (89,2) |

35,2 (95,4) |

37,5 (99,5) |

37,0 (98,6) |

31,8 (89,2) |

28,2 (82,8) |

24,2 (75,6) |

21,7 (71,1) |

37,5 (99,5) |

| Moyenne élevée °C (°F) | 3,5 (38,3) |

5,0 (41,0) |

9,5 (49,1) |

14,2 (57,6) |

19,1 (66,4) |

21,9 (71,4) |

24,4 (75,9) |

23,9 (75,0) |

19,4 (66,9) |

14,3 (57,7) |

7,7 (45,9) |

4,2 (39,6) |

13,9 (57,0) |

| Moyenne quotidienne °C (°F) | 0,3 (32,5) |

1,4 (34,5) |

5,3 (41,5) |

9,4 (48,9) |

14,3 (57,7) |

17,2 (63,0) |

19,4 (66,9) |

18,9 (66,0) |

14,7 (58,5) |

10,1 (50,2) |

4,4 (39,9) |

1,3 (34,3) |

9,7 (49,5) |

| Moyenne basse °C (°F) | −2,5 (27,5) |

−1,9 (28,6) |

1,6 (34,9) |

4,9 (40,8) |

9,4 (48,9) |

12,5 (54,5) |

14,5 (58,1) |

14,2 (57,6) |

10,5 (50,9) |

6,6 (43,9) |

1,7 (35,1) |

−1,2 (29,8) |

5,9 (42,6) |

| Record bas °C (°F) | −22,2 (−8,0) |

−25,4 (−13,7) |

−16,0 (3,2) |

−6,0 (21,2) |

−2,3 (27,9) |

1,0 (33,8) |

6,5 (43,7) |

4,8 (40,6) |

0,6 (33,1) |

−4,5 (23,9) |

−11,0 (12,2) |

−20,7 (−5,3) |

−25,4 (−13,7) |

| Précipitations moyennes mm (pouces) | 48 (1,9) |

46 (1.8) |

65 (2,6) |

65 (2,6) |

101 (4.0) |

118 (4,6) |

122 (4,8) |

115 (4,5) |

75 (3.0) |

65 (2,6) |

61 (2.4) |

65 (2,6) |

944 (37,2) |

| Heures d’ensoleillement mensuelles moyennes | 79 | 96 | 133 | 170 | 209 | 210 | 238 | 220 | 163 | 125 | 75 | 59 | 1 777 |

| Source 1 : DWD [58] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2 : SKlima.de [59] |

Changement climatique

A Munich, on observe également la tendance générale au réchauffement climatique avec une augmentation des températures annuelles moyennes d’environ 1 °C en Allemagne au cours des 120 dernières années. En novembre 2016, le conseil municipal a conclu officiellement qu’une nouvelle augmentation de la température moyenne, un nombre plus élevé de chaleurs extrêmes, une augmentation du nombre de jours et de nuits chauds avec des températures supérieures à 20 ° C ( nuits tropicales ), un changement dans les régimes de précipitations , ainsi qu’une augmentation du nombre de cas locaux de fortes pluies , sont à prévoir dans le cadre du changement climatique en cours. [60]L’administration municipale a décidé de soutenir une étude conjointe de son propre Referat für Gesundheit und Umwelt (département pour les questions de santé et d’environnement) et du service météorologique allemand qui rassemblera des données sur la météo locale. Les données sont censées être utilisées pour créer un plan d’action pour adapter la ville afin de mieux faire face au changement climatique ainsi qu’un programme d’action intégré pour la protection du climat à Munich. Avec l’aide de ces programmes, les problèmes d’aménagement du territoire et de densité de peuplement, le développement des bâtiments et des espaces verts ainsi que les plans de ventilation fonctionnelle dans un paysage urbain peuvent être surveillés et gérés. [61]

Démographie

| An | Populaire. | ± % |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 13 447 | — |

| 1600 | 21 943 | +63,2% |

| 1750 | 32 000 | +45,8% |

| 1880 | 230 023 | +618,8% |

| 1890 | 349 024 | +51,7% |

| 1900 | 499 932 | +43,2% |

| 1910 | 596 467 | +19,3% |

| 1920 | 666 000 | +11,7% |

| 1930 | 728 900 | +9,4% |

| 1940 | 834 500 | +14,5% |

| 1950 | 823 892 | −1,3 % |

| 1955 | 929 808 | +12,9% |

| 1960 | 1 055 457 | +13,5% |

| 1965 | 1 214 603 | +15,1% |

| 1970 | 1 311 978 | +8,0 % |

| 1980 | 1 298 941 | −1,0 % |

| 1990 | 1 229 026 | −5,4 % |

| 2000 | 1 210 223 | −1,5 % |

| 2005 | 1 259 584 | +4,1% |

| 2010 | 1 353 186 | +7,4% |

| 2011 | 1 364 920 | +0,9 % |

| 2012 | 1 388 308 | +1,7% |

| 2013 | 1 402 455 | +1,0 % |

| 2015 | 1 450 381 | +3,4% |

| 2018 | 1 471 508 | +1,5% |

| 2020 | 1 488 202 | +1,1% |

De seulement 24 000 habitants en 1700, la population de la ville doublait environ tous les 30 ans. Elle était de 100 000 en 1852, 250 000 en 1883 et 500 000 en 1901. Depuis, Munich est devenue la troisième ville d’Allemagne. En 1933, on comptait 840 901 habitants, et en 1957 plus d’un million.

Immigration

En juillet 2017, Munich comptait 1,42 million d’habitants ; 421 832 ressortissants étrangers résidaient dans la ville au 31 décembre 2017, 50,7% de ces résidents étant des citoyens des États membres de l’UE et 25,2% des citoyens d’États européens non membres de l’UE (y compris la Russie et la Turquie). [62] Les plus grands groupes de ressortissants étrangers étaient les Turcs (39 204), les Croates (33 177), les Italiens (27 340), les Grecs (27 117), les Polonais (27 945), les Autrichiens (21 944) et les Roumains (18 085).

| Résidents étrangers par nationalité d’ici fin 2020 [63] | |

| Pays | Population |

|---|---|

| |

39 145 |

| |

37 207 |

| |

28 496 |

| |

26 613 |

| |

21 559 |

| |

20 741 |

| |

18 845 |

| |

18 639 |

| |

14 283 |

| |

13 636 |

| |

11 854 |

| |

11 228 |

| |

11 093 |

| |

10 650 |

| |

9 526 |

| |

9 414 |

| |

9 240 |

| |

8 269 |

| |

7 446 |

| |

7 133 |

| |

6 705 |

| |

4 899 |

| |

4 614 |

| |

4 297 |

La religion

Environ 45 % des habitants de Munich ne sont affiliés à aucun groupe religieux ; CE ratio représente le segment de la population qui connaît la croissance la plus rapide. Comme dans le reste de l’Allemagne, les églises catholiques et protestantes ont connu une baisse continue de leurs effectifs. Au 31 décembre 2017, 31,8 % des habitants de la ville étaient catholiques , 11,4 % protestants , 0,3 % juifs [64] et 3,6 % étaient membres d’une Église orthodoxe ( orthodoxe oriental ou orthodoxe oriental ). [65] Environ 1 % adhèrent à d’autres dénominations chrétiennes. Il y a aussi une petite paroisse vieille-catholique et une paroisse anglophone du église épiscopaledans la ville. Selon l’Office statistique de Munich, en 2013, environ 8,6 % de la population munichoise était musulmane . [66]

Gouvernement

Chancellerie d’État de Bavière

Chancellerie d’État de Bavière

En tant que capitale de la Bavière, Munich est un centre politique important pour l’État et le pays dans son ensemble. C’est le siège du Landtag de Bavière , de la Chancellerie d’État et de tous les départements de l’État. Plusieurs autorités nationales et internationales sont situées à Munich, notamment la Cour fédérale des finances d’Allemagne et l’ Office européen des brevets .

Maire

L’actuel maire de Munich est Dieter Reiter du Parti social-démocrate (SPD) de centre gauche , qui a été élu en 2014 et réélu en 2020. Munich a une tradition de gauche beaucoup plus forte que le reste de l’État, qui a été dominée par l’ Union chrétienne-sociale conservatrice de Bavière (CSU) au niveau fédéral, étatique et local depuis la création de la République fédérale en 1949. Munich, en revanche, a été gouvernée par le SPD pendant presque six ans depuis 1948 Depuis les élections locales de 2020, les partis verts et de centre-gauche détiennent également la majorité au conseil municipal ( Stadtrat ).

La dernière élection du maire a eu lieu le 15 mars 2020, avec un second tour le 29 mars, et les résultats ont été les suivants :

| Candidat | Faire la fête | Premier tour | Deuxième tour | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||

| Dieter Reiter | Parti social-démocrate | 259 928 | 47,9 | 401 856 | 71,7 |

| Kristina Franck | Union chrétienne-sociale | 115 795 | 21.3 | 158 773 | 28.3 |

| Katrin Habenschaden | Alliance 90/Les Verts | 112 121 | 20.7 | ||

| Wolfgang Wiehle | Alternative pour l’Allemagne | 14 988 | 2.8 | ||

| Tobias Ruff | Parti démocrate écologique | 8 464 | 1.6 | ||

| Jörg Hoffmann | Parti démocrate libre | 8 201 | 1.5 | ||

| Thomas Lecher | La gauche | 7 232 | 1.3 | ||

| Hans-Peter Mehling | Électeurs libres de Bavière | 5 003 | 0,9 | ||

| Moritz Weixler | Die PARTEI | 3 508 | 0,6 | ||

| Dirk Hopner | Liste munichoise | 1 966 | 0,4 | ||

| Richard Progl | Fête bavaroise | 1 958 | 0,4 | ||

| Ender Beyhan-Bilgin | ÉQUITABLE | 1 483 | 0,3 | ||

| Stéphanie Dilba | muet | 1 267 | 0,2 | ||

| Cétin Oraner | Ensemble Bavière | 819 | 0,2 | ||

| Votes valides | 542 733 | 99,6 | 560 629 | 99,7 | |

| Votes invalides | 1 997 | 0,4 | 1 616 | 0,3 | |

| Total | 544 730 | 100,0 | 562 245 | 100,0 | |

| Électorat/participation électorale | 1 110 571 | 49,0 | 1 109 032 | 50,7 | |

| Source : Wahlen München ( 1er tour , 2e tour ) |

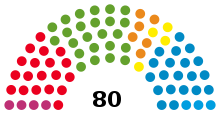

Conseil municipal

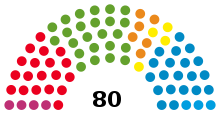

Groupes dans le conseil.

Groupes dans le conseil.

Gauche / PARTEI : 4 places

SPD / Volt : 19 sièges

Liste verte /rose : 24 sièges

ÖDP / FW : 6 sièges

FDP / BP : 4 sièges

CSU : 20 sièges

AfD : 3 sièges

Le conseil municipal de Munich ( Stadtrat ) gouverne la ville aux côtés du maire. La dernière élection du conseil municipal a eu lieu le 15 mars 2020 et les résultats ont été les suivants :

| Faire la fête | Candidat principal | Votes | % | +/- | Des places | +/- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance 90/Les Verts (Grüne) | Katrin Habenschaden | 11 762 516 | 29.1 | |

23 | |

| Union chrétienne-sociale (CSU) | Kristina Franck | 9 986 014 | 24,7 | |

20 | |

| Parti social-démocrate (SPD) | Dieter Reiter | 8 884 562 | 22,0 | |

18 | |

| Parti démocrate écologique (ÖDP) | Tobias Ruff | 1 598 539 | 4.0 | |

3 | |

| Alternative pour l’Allemagne (AfD) | Iris Wassil | 1 559 476 | 3.9 | |

3 | |

| Parti libéral démocrate (FDP) | Jörg Hoffmann | 1 420 194 | 3.5 | |

3 | ±0 |

| La gauche (Die Linke) | Stefan Jagel | 1 319 464 | 3.3 | |

3 | |

| Électeurs libres de Bavière (FW) | Hans-Peter Mehling | 1 008 400 | 2.5 | |

2 | ±0 |

| Volt Allemagne (Volt) | Félix Sproll | 732 853 | 1.8 | Nouveau | 1 | Nouveau |

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | Marie Burneleit | 528 949 | 1.3 | Nouveau | 1 | Nouveau |

| Liste rose (Rosa Liste) | Thomas Niederbuhl | 396 324 | 1.0 | |

1 | ±0 |

| Liste munichoise | Dirk Hopner | 339 705 | 0,8 | Nouveau | 1 | Nouveau |

| Parti bavarois (BP) | Richard Progl | 273 737 | 0,7 | |

1 | ±0 |

| muet | Stéphanie Dilba | 247 679 | 0,6 | Nouveau | 0 | Nouveau |

| ÉQUITABLE | Kemal Orak | 142 455 | 0,4 | Nouveau | 0 | Nouveau |

| Ensemble Bavière (ZuBa) | Cétin Oraner | 120 975 | 0,3 | Nouveau | 0 | Nouveau |

| BIA | Karl Richter | 86 358 | 0,2 | |

0 | ±0 |

| Votes valides | 531 527 | 97,6 | ||||

| Votes invalides | 12 937 | 2.4 | ||||

| Total | 544 464 | 100,0 | 80 | ±0 | ||

| Électorat/participation électorale | 1 110 571 | 49,0 | |

|||

| Source : Wahlen München |

Villes sœurs

Plaque in the Neues Rathaus (New City Hall) showing Munich’s twin towns and sister cities

Plaque in the Neues Rathaus (New City Hall) showing Munich’s twin towns and sister cities

Munich is twinned with the following cities (date of agreement shown in parentheses):[67] Edinburgh, Scotland (1954)[68][69], Verona, Italy (March 17, 1960)[70][71], Bordeaux, France (1964)[72][73], Sapporo, Japan (1972),[74] Cincinnati, Ohio, United States (1989), Kyiv, Ukraine (1989) and Harare, Zimbabwe (1996).

Subdivisions

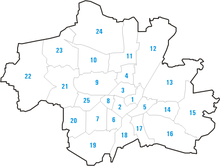

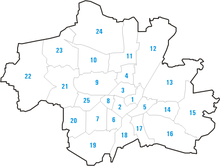

Munich’s Boroughs

Munich’s Boroughs

Since the administrative reform in 1992, Munich is divided into 25 boroughs or Stadtbezirke, which themselves consist of smaller quarters.

Allach-Untermenzing (23), Altstadt-Lehel (1), Aubing-Lochhausen-Langwied (22), Au-Haidhausen (5), Berg am Laim (14), Bogenhausen (13), Feldmoching-Hasenbergl (24), Hadern (20), Laim (25), Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt (2), Maxvorstadt (3), Milbertshofen-Am Hart (11), Moosach (10), Neuhausen-Nymphenburg (9), Obergiesing (17), Pasing-Obermenzing (21), Ramersdorf-Perlach (16), Schwabing-Freimann (12), Schwabing-West (4), Schwanthalerhöhe (8), Sendling (6), Sendling-Westpark (7), Thalkirchen-Obersendling-Forstenried-Fürstenried-Solln (19), Trudering-Riem (15) and Untergiesing-Harlaching (18).

Architecture

The New Town Hall and Marienplatz

The New Town Hall and Marienplatz

Frauenkirche

Frauenkirche

Viktualienmarkt with the Altes Rathaus

Viktualienmarkt with the Altes Rathaus

The city has an eclectic mix of historic and modern architecture because historic buildings destroyed in World War II were reconstructed, and new landmarks were built. A survey by the Society’s Centre for Sustainable Destinations for the National Geographic Traveller chose over 100 historic destinations around the world and ranked Munich 30th.[75]

Inner city

Wittelsbach Square at night, 1890, by Aleksander Gierymski

Wittelsbach Square at night, 1890, by Aleksander Gierymski

At the centre of the city is the Marienplatz – a large open square named after the Mariensäule, a Marian column in its centre – with the Old and the New Town Hall. Its tower contains the Rathaus-Glockenspiel. Three gates of the demolished medieval fortification survive – the Isartor in the east, the Sendlinger Tor in the south and the Karlstor in the west of the inner city. The Karlstor leads up to the Stachus, a square dominated by the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice) and a fountain.

The Peterskirche close to Marienplatz is the oldest church of the inner city. It was first built during the Romanesque period, and was the focus of the early monastic settlement in Munich before the city’s official foundation in 1158. Nearby St. Peter the Gothic hall-church Heiliggeistkirche (The Church of the Holy Spirit) was converted to baroque style from 1724 onwards and looks down upon the Viktualienmarkt.

The Frauenkirche serves as the cathedral for the Catholic Archdiocese of Munich and Freising. The nearby Michaelskirche is the largest renaissance church north of the Alps, while the Theatinerkirche is a basilica in Italianate high baroque, which had a major influence on Southern German baroque architecture. Its dome dominates the Odeonsplatz. Other baroque churches in the inner city include the Bürgersaalkirche, the Trinity Church and the St. Anna Damenstiftskirche. The Asamkirche was endowed and built by the Brothers Asam, pioneering artists of the rococo period.

The large Residenz palace complex (begun in 1385) on the edge of Munich’s Old Town, Germany’s largest urban palace, ranks among Europe’s most significant museums of interior decoration. Having undergone several extensions, it contains also the treasury and the splendid rococo Cuvilliés Theatre. Next door to the Residenz the neo-classical opera, the National Theatre was erected. Among the baroque and neoclassical mansions which still exist in Munich are the Palais Porcia, the Palais Preysing, the Palais Holnstein and the Prinz-Carl-Palais. All mansions are situated close to the Residenz, same as the Alte Hof, a medieval castle and first residence of the Wittelsbach dukes in Munich.

Lehel, a middle-class quarter east of the Altstadt, is characterised by numerous well-preserved townhouses. The St. Anna im Lehel is the first rococo church in Bavaria. St. Lukas is the largest Protestant Church in Munich.

Royal avenues and squares

Ludwigstraße from above, Highlight Towers in the background

Ludwigstraße from above, Highlight Towers in the background

Four grand royal avenues of the 19th century with official buildings connect Munich’s inner city with its then-suburbs:

The neoclassical Brienner Straße, starting at Odeonsplatz on the northern fringe of the Old Town close to the Residenz, runs from east to west and opens into the Königsplatz, designed with the “Doric” Propyläen, the “Ionic” Glyptothek and the “Corinthian” State Museum of Classical Art, behind it St. Boniface’s Abbey was erected. The area around Königsplatz is home to the Kunstareal, Munich’s gallery and museum quarter (as described below).

Ludwigstraße also begins at Odeonsplatz and runs from south to north, skirting the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, the St. Louis church, the Bavarian State Library and numerous state ministries and palaces. The southern part of the avenue was constructed in Italian renaissance style, while the north is strongly influenced by Italian Romanesque architecture. The Siegestor (gate of victory) sits at the northern end of Ludwigstraße, where the latter passes over into Leopoldstraße and the district of Schwabing begins.

Königsplatz

Königsplatz

The neo-Gothic Maximilianstraße starts at Max-Joseph-Platz, where the Residenz and the National Theatre are situated, and runs from west to east. The avenue is framed by elaborately structured neo-Gothic buildings which house, among others, the Schauspielhaus, the Building of the district government of Upper Bavaria and the Museum of Ethnology. After crossing the River Isar, the avenue circles the Maximilianeum, which houses the state parliament. The western portion of Maximilianstraße is known for its designer shops, luxury boutiques, jewellery stores, and one of Munich’s foremost five-star hotels, the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten.

Prinzregentenstraße runs parallel to Maximilianstraße and begins at Prinz-Carl-Palais. Many museums are on the avenue, such as the Haus der Kunst, the Bavarian National Museum and the Schackgalerie. The avenue crosses the Isar and circles the Friedensengel monument, then passing the Villa Stuck and Hitler’s old apartment. The Prinzregententheater is at Prinzregentenplatz further to the east.

Other boroughs

In Schwabing and Maxvorstadt, many beautiful streets with continuous rows of Gründerzeit buildings can be found. Rows of elegant town houses and spectacular urban palais in many colours, often elaborately decorated with ornamental details on their façades, make up large parts of the areas west of Leopoldstraße (Schwabing’s main shopping street), while in the eastern areas between Leopoldstraße and Englischer Garten similar buildings alternate with almost rural-looking houses and whimsical mini-castles, often decorated with small towers. Numerous tiny alleys and shady lanes connect the larger streets and little plazas of the area, conveying the legendary artist’s quarter’s flair and atmosphere convincingly like it was at the turn of the 20th century. The wealthy district of Bogenhausen in the east of Munich is another little-known area (at least among tourists) rich in extravagant architecture, especially around Prinzregentenstraße. One of Bogenhausen’s most beautiful buildings is Villa Stuck, famed residence of painter Franz von Stuck.

Nymphenburg Palace

Nymphenburg Palace

Two large Baroque palaces in Nymphenburg and Oberschleissheim are reminders of Bavaria’s royal past. Schloss Nymphenburg (Nymphenburg Palace), some 6 km (4 mi) north west of the city centre, is surrounded by an park and is considered[by whom?] to be one of Europe’s most beautiful royal residences. 2 km (1 mi) northwest of Nymphenburg Palace is Schloss Blutenburg (Blutenburg Castle), an old ducal country seat with a late-Gothic palace church. Schloss Fürstenried (Fürstenried Palace), a baroque palace of similar structure to Nymphenburg but of much smaller size, was erected around the same time in the south west of Munich.

Schleissheim Palace

Schleissheim Palace

The second large Baroque residence is Schloss Schleissheim (Schleissheim Palace), located in the suburb of Oberschleissheim, a palace complex encompassing three separate residences: Altes Schloss Schleissheim (the old palace), Neues Schloss Schleissheim (the new palace) and Schloss Lustheim (Lustheim Palace). Most parts of the palace complex serve as museums and art galleries. Deutsches Museum’s Flugwerft Schleissheim flight exhibition centre is located nearby, on the Schleissheim Special Landing Field. The Bavaria statue before the neo-classical Ruhmeshalle is a monumental, bronze sand-cast 19th-century statue at Theresienwiese. The Grünwald castle is the only medieval castle in the Munich area which still exists.

BMW Headquarters

BMW Headquarters

St Michael in Berg am Laim is a church in the suburbs. Another church of Johann Michael Fischer is St George in Bogenhausen. Most of the boroughs have parish churches that originate from the Middle Ages, such as the church of pilgrimage St Mary in Ramersdorf. The oldest church within the city borders is Heilig Kreuz in Fröttmaning next to the Allianz-Arena, known for its Romanesque fresco. Moosach features one of the oldest churches, Alt-St. Martin, but a larger one was built in 1925.

Especially in its suburbs, Munich features a wide and diverse array of modern architecture, although strict culturally sensitive height limitations for buildings have limited the construction of skyscrapers to avoid a loss of views to the distant Bavarian Alps. Most high-rise buildings are clustered at the northern edge of Munich in the skyline, like the Hypo-Haus, the Arabella High-Rise Building, the Highlight Towers, Uptown Munich, Münchner Tor and the BMW Headquarters next to the Olympic Park. Several other high-rise buildings are located near the city centre and on the Siemens campus in southern Munich. A landmark of modern Munich is also the architecture of the sport stadiums (as described below).

In Fasangarten is the former McGraw Kaserne, a former US army base, near Stadelheim Prison.

Parks

Hofgarten with the dome of the state chancellery near the Residenz

Hofgarten with the dome of the state chancellery near the Residenz

Munich is a densely-built city but has numerous public parks. In 1789, the Englischer Garten was created just north of Munich’s old city center. Covering an area of 3.7 km2 (1.4 sq mi), it is larger than Central Park in New York City, and it is one of the world’s largest urban public parks.[76] It contains a naturist (nudist) area, numerous bicycle and jogging tracks as well as bridle-paths. It was designed and laid out by Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, both for pleasure and as a work area for the city’s vagrants and homeless. Nowadays it is entirely a park, its southern half being dominated by wide-open areas, hills, monuments and beach-like stretches (along the streams Eisbach and Schwabinger Bach). In contrast, its less-frequented northern part is much quieter, with many old trees and thick undergrowth. Multiple beer gardens can be found in both parts of the Englischer Garten, the most well-known being located at the Chinese Pagoda.

Other large green spaces are the modern Olympiapark, the Westpark, and the parks of Nymphenburg Palace (with the Botanischer Garten München-Nymphenburg to the north), and Schleissheim Palace. The city’s oldest park is the Hofgarten, near the Residenz, dating back to the 16th century. The site of the largest beer garden in town, the former royal Hirschgarten was founded in 1780 for deer, which still live there.

The city’s zoo is the Tierpark Hellabrunn near the Flaucher Island in the Isar in the south of the city. Another notable park is Ostpark located in the Ramersdorf-Perlach borough which also houses the Michaelibad, the largest water park in Munich.

Sports

Allianz Arena, the home stadium of Bayern Munich

Allianz Arena, the home stadium of Bayern Munich

Olympiasee in Olympiapark, Munich

Olympiasee in Olympiapark, Munich

Football

Munich is home to several professional football teams including Bayern Munich, Germany’s most successful club and a multiple UEFA Champions League winner. Other notable clubs include 1860 Munich, who were long time their rivals on a somewhat equal footing, but currently play in the 3rd Division 3. Liga along with another former Bundesliga club SpVgg Unterhaching.

Basketball

FC Bayern Munich Basketball is currently playing in the Beko Basket Bundesliga. The city hosted the final stages of the FIBA EuroBasket 1993, where the German national basketball team won the gold medal.

Ice hockey

The city’s ice hockey club is EHC Red Bull München who play in the Deutsche Eishockey Liga. The team has won three DEL Championships, in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Olympics

Munich hosted the 1972 Summer Olympics; the Munich Massacre took place in the Olympic village. It was one of the host cities for the 2006 Football World Cup, which was not held in Munich’s Olympic Stadium, but in a new football specific stadium, the Allianz Arena. Munich bid to host the 2018 Winter Olympic Games, but lost to Pyeongchang.[77] In September 2011 the DOSB President Thomas Bach confirmed that Munich would bid again for the Winter Olympics in the future.[78]

Road running

Regular annual road running events in Munich are the Munich Marathon in October, the Stadtlauf end of June, the company run B2Run in July, the New Year’s Run on 31 December, the Spartan Race Sprint, the Olympia Alm Crosslauf and the Bestzeitenmarathon.

Swimming

Public sporting facilities in Munich include ten indoor swimming pools[79] and eight outdoor swimming pools,[80] which are operated by the Munich City Utilities (SWM) communal company.[81] Popular indoor swimming pools include the Olympia Schwimmhalle of the 1972 Summer Olympics, the wave pool Cosimawellenbad, as well as the Müllersches Volksbad which was built in 1901. Further, swimming within Munich’s city limits is also possible in several artificial lakes such as for example the Riemer See or the Langwieder lake district.[82]

River surfing

Munich has a reputation as a surfing hotspot, offering the world’s best known river surfing spot, the Eisbach wave, which is located at the southern edge of the Englischer Garten park and used by surfers day and night and throughout the year.[83] Half a kilometre down the river, there is a second, easier wave for beginners, the so-called Kleine Eisbachwelle. Two further surf spots within the city are located along the River Isar, the wave in the Floßlände channel and a wave downstream of the Wittelsbacherbrücke bridge.[84]

Culture

Language

The Bavarian dialects are spoken in and around Munich, with its variety West Middle Bavarian or Old Bavarian (Westmittelbairisch / Altbairisch). Austro-Bavarian has no official status by the Bavarian authorities or local government, yet is recognised by the SIL and has its own ISO-639 code.

Museums

The Glyptothek

The Glyptothek

Bavarian National Museum

Bavarian National Museum

The Deutsches Museum or German Museum, located on an island in the River Isar, is the largest and one of the oldest science museums in the world. Three redundant exhibition buildings that are under a protection order were converted to house the Verkehrsmuseum, which houses the land transport collections of the Deutsches Museum. Deutsches Museum’s Flugwerft Schleissheim flight exhibition centre is located nearby, on the Schleissheim Special Landing Field. Several non-centralised museums (many of those are public collections at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität) show the expanded state collections of palaeontology, geology, mineralogy,[85] zoology, botany and anthropology.

The city has several important art galleries, most of which can be found in the Kunstareal, including the Alte Pinakothek, the Neue Pinakothek, the Pinakothek der Moderne and the Museum Brandhorst. The Alte Pinakothek contains a treasure trove of the works of European masters between the 14th and 18th centuries. The collection reflects the eclectic tastes of the Wittelsbachs over four centuries and is sorted by schools over two floors. Major displays include Albrecht Dürer’s Christ-like Self-Portrait (1500), his Four Apostles, Raphael’s paintings The Canigiani Holy Family and Madonna Tempi as well as Peter Paul Rubens large Judgment Day. The gallery houses one of the world’s most comprehensive Rubens collections. The Lenbachhaus houses works by the group of Munich-based modernist artists known as Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider).

The gothic Morris dancers of Erasmus Grasser are exhibited in the Munich City Museum in the old gothic arsenal building in the inner city.

Another area for the arts next to the Kunstareal is the Lehel quarter between the old town and the River Isar: the Museum Five Continents in Maximilianstraße is the second largest collection in Germany of artefacts and objects from outside Europe, while the Bavarian National Museum and the adjoining Bavarian State Archaeological Collection in Prinzregentenstraße rank among Europe’s major art and cultural history museums. The nearby Schackgalerie is an important gallery of German 19th-century paintings.

The former Dachau concentration camp is 16 km (10 mi) outside the city.

Arts and literature

National Theatre

National Theatre

Munich is a major international cultural centre and has played host to many prominent composers including Orlando di Lasso, W.A. Mozart, Carl Maria von Weber, Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Max Reger and Carl Orff. With the Munich Biennale founded by Hans Werner Henze, and the A*DEvantgarde festival, the city still contributes to modern music theatre. Some of classical music’s best-known pieces have been created in and around Munich by composers born in the area, for example, Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra or Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana.

At the Nationaltheater several of Richard Wagner’s operas were premiered under the patronage of Ludwig II of Bavaria. It is the home of the Bavarian State Opera and the Bavarian State Orchestra. Next door, the modern Residenz Theatre was erected in the building that had housed the Cuvilliés Theatre before World War II. Many operas were staged there, including the premiere of Mozart’s Idomeneo in 1781. The Gärtnerplatz Theatre is a ballet and musical state theatre while another opera house, the Prinzregententheater, has become the home of the Bavarian Theatre Academy and the Munich Chamber Orchestra.

Gasteig

Gasteig

The modern Gasteig centre houses the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra. The third orchestra in Munich with international importance is the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Its primary concert venue is the Herkulessaal in the former city royal residence, the Munich Residenz. Many important conductors have been attracted by the city’s orchestras, including Felix Weingartner, Hans Pfitzner, Hans Rosbaud, Hans Knappertsbusch, Sergiu Celibidache, James Levine, Christian Thielemann, Lorin Maazel, Rafael Kubelík, Eugen Jochum, Sir Colin Davis, Mariss Jansons, Bruno Walter, Georg Solti, Zubin Mehta and Kent Nagano. A stage for shows, big events and musicals is the Deutsche Theater. It is Germany’s largest theatre for guest performances.

Munich’s contributions to modern popular music are often overlooked in favour of its strong association with classical music, but they are numerous: the city has had a strong music scene in the 1960s and 1970s, with many internationally renowned bands and musicians frequently performing in its clubs. Furthermore, Munich was the centre of Krautrock in southern Germany, with many important bands such as Amon Düül II, Embryo or Popol Vuh hailing from the city. In the 1970s, the Musicland Studios developed into one of the most prominent recording studios in the world, with bands such as the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Queen recording albums there. Munich also played a significant role in the development of electronic music, with genre pioneer Giorgio Moroder, who invented synth disco and electronic dance music, and Donna Summer, one of disco music’s most important performers, both living and working in the city. In the late 1990s, Electroclash was substantially co-invented if not even invented in Munich, when DJ Hell introduced and assembled international pioneers of this musical genre through his International DeeJay Gigolo Records label here.[86] Other examples of notable musicians and bands from Munich are Konstantin Wecker, Willy Astor, Spider Murphy Gang, Münchener Freiheit, Lou Bega, Megaherz, FSK, Colour Haze and Sportfreunde Stiller.

Music is so important in the Bavarian capital that the city hall gives permissions every day to ten musicians for performing in the streets around Marienplatz. This is how performers such as Olga Kholodnaya and Alex Jacobowitz are entertaining the locals and the tourists every day.

Next to the Bavarian Staatsschauspiel in the Residenz Theatre (Residenztheater), the Munich Kammerspiele in the Schauspielhaus is one of the most important German-language theatres in the world. Since Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s premieres in 1775 many important writers have staged their plays in Munich such as Christian Friedrich Hebbel, Henrik Ibsen and Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

The city is known as the second-largest publishing centre in the world (around 250 publishing houses have offices in the city), and many national and international publications are published in Munich, such as Arts in Munich, LAXMag and Prinz.

Vassily Kandinsky’s Houses in Munich (1908)

Vassily Kandinsky’s Houses in Munich (1908)

At the turn of the 20th century, Munich, and especially its suburb of Schwabing, was the preeminent cultural metropolis of Germany. Its importance as a centre for both literature and the fine arts was second to none in Europe, with numerous German and non-German artists moving there. For example, Wassily Kandinsky chose Munich over Paris to study at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, and, along with many other painters and writers living in Schwabing at that time, had a profound influence on modern art.

Des personnalités littéraires éminentes ont travaillé à Munich, en particulier pendant les dernières décennies du royaume de Bavière, le soi-disant Prinzregentenzeit (littéralement “le temps du prince régent”) sous le règne de Luitpold, prince régent de Bavière , une période souvent décrite comme un âge d’or culturel. pour Munich et la Bavière dans son ensemble. Certains des plus notables étaient Thomas Mann , Heinrich Mann , Paul Heyse , Rainer Maria Rilke , Ludwig Thoma , Fanny zu Reventlow , Oskar Panizza , Gustav Meyrink , Max Halbe , Erich Mühsam et Frank Wedekind .. Pendant une courte période, Vladimir Lénine a vécu à Schwabing, où il a écrit et publié son ouvrage le plus important, Que faire ? Au centre de la scène bohème de Schwabing (bien qu’ils soient en fait souvent situés dans le quartier voisin de Maxvorstadt) se trouvaient les Künstlerlokale (cafés d’artistes) comme le Café Stefanie ou le Kabarett Simpl , dont les manières libérales différaient fondamentalement des localités plus traditionnelles de Munich. Le Simpl, qui survit à CE jour (bien qu’avec peu de pertinence pour la scène artistique contemporaine de la ville), a été nommé d’après le magazine satirique anti-autoritaire de Munich Simplicissimus , fondé en 1896 par Albert Langen et Thomas Theodor Heine ., qui devint rapidement un orgue important de la Schwabinger Bohème . Ses caricatures et ses attaques satiriques mordantes contre la société allemande de Wilhelmine sont le résultat d’innombrables efforts de collaboration de la part de nombreux artistes visuels et écrivains de Munich et d’ailleurs.

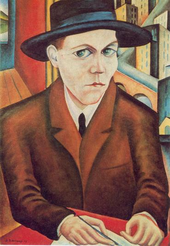

Portrait d’ Oskar Maria Graf par Georg Schrimpf (1927)

Portrait d’ Oskar Maria Graf par Georg Schrimpf (1927)

La période précédant immédiatement la Première Guerre mondiale a vu l’importance économique et culturelle continue de la ville. Thomas Mann a écrit dans sa nouvelle Gladius Dei à propos de cette période : « München leuchtete » (littéralement « Munich brillait »). Munich est restée un centre de la vie culturelle pendant la période de Weimar, avec des personnalités telles que Lion Feuchtwanger , Bertolt Brecht , Peter Paul Althaus , Stefan George , Ricarda Huch , Joachim Ringelnatz , Oskar Maria Graf , Annette Kolb , Ernst Toller , Hugo Ball et Klaus Mann .s’ajoutant aux grands noms déjà établis. Karl Valentin était l’artiste de cabaret et comédien le plus important d’Allemagne et est à CE jour bien connu et aimé comme une icône culturelle de sa ville natale. Entre 1910 et 1940, il écrit et joue dans de nombreux sketches absurdes et courts métrages très influents, CE qui lui vaut le surnom de “Charlie Chaplin d’Allemagne”. De nombreuses œuvres de Valentin ne seraient pas imaginables sans sa sympathique partenaire féminine Liesl Karlstadt , qui jouait souvent des personnages masculins avec un effet hilarant dans leurs croquis. Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Munich est rapidement redevenue un point central de la scène littéraire allemande et le reste à CE jour, avec des écrivains aussi divers que Wolfgang Koeppen , Erich Kästner, Eugen Roth , Alfred Andersch , Elfriede Jelinek , Hans Magnus Enzensberger , Michael Ende , Franz Xaver Kroetz , Gerhard Polt , John Vincent Palatine et Patrick Süskind ont élu domicile dans la ville.

De l’époque gothique à l’époque baroque, les beaux-arts étaient représentés à Munich par des artistes comme Erasmus Grasser , Jan Polack , Johann Baptist Straub , Ignaz Günther , Hans Krumpper , Ludwig von Schwanthaler , Cosmas Damian Asam , Egid Quirin Asam , Johann Baptist Zimmermann , Johann Michael Fischer et François de Cuvilliés . Munich était déjà devenu un lieu important pour des peintres comme Carl Rottmann , Lovis Corinth , Wilhelm von Kaulbach , Carl Spitzweg ,Franz von Lenbach , Franz von Stuck , Karl Piloty et Wilhelm Leibl lorsque Der Blaue Reiter (Le Cavalier bleu), un groupe d’artistes expressionnistes, s’est établi à Munich en 1911. La ville abritait les peintres du Cavalier bleu Paul Klee , Wassily Kandinsky , Alexej von Jawlensky , Gabriele Münter , Franz Marc , August Macke et Alfred Kubin . La première peinture abstraite de Kandinsky a été créée à Schwabing.

Munich était (et dans certains cas, est toujours) le foyer de plusieurs des auteurs les plus importants du mouvement du nouveau cinéma allemand , dont Rainer Werner Fassbinder , Werner Herzog , Edgar Reitz et Herbert Achternbusch . En 1971, le Filmverlag der Autoren a été fondé, cimentant le rôle de la ville dans l’histoire du mouvement. Munich a servi de décor à de nombreux films de Fassbinder, dont Ali : la peur mange l’âme . L’hôtel Deutsche Eicheprès de Gärtnerplatz ressemblait un peu à un centre d’opérations pour Fassbinder et son “clan” d’acteurs. Le nouveau cinéma allemand est considéré de loin comme le mouvement artistique le plus important de l’histoire du cinéma allemand depuis l’ère de l’expressionnisme allemand dans les années 1920.

Logo de Bavaria Film

Logo de Bavaria Film

En 1919, les Bavaria Film Studios ont été fondés, qui sont devenus l’un des plus grands studios de cinéma d’Europe. Des réalisateurs comme Alfred Hitchcock , Billy Wilder , Orson Welles , John Huston , Ingmar Bergman , Stanley Kubrick , Claude Chabrol , Fritz Umgelter , Rainer Werner Fassbinder , Wolfgang Petersen et Wim Wenders y ont réalisé des films. Parmi les films de renommée internationale produits dans les studios figurent The Pleasure Garden (1925) d’Alfred Hitchcock, The Great Escape (1963) deJohn Sturges , Paths of Glory (1957) de Stanley Kubrick, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) de Mel Stuart et Das Boot (1981) et The Neverending Story (1984) de Wolfgang Petersen . Munich reste l’un des centres de l’industrie allemande du cinéma et du divertissement.

Festivals

Oktoberfest

Oktoberfest

Salon annuel “High End Munich”. [87]

Starkbierfest

Mars et avril, à l’échelle de la ville : [88] Starkbierfest a lieu pendant trois semaines pendant le Carême , entre Carnaval et Pâques , [89] célébrant la « bière forte » de Munich . La Starkbier a été créée en 1651 par les moines Paulaner locaux qui buvaient CE « Flüssiges Brot », ou « pain liquide », pour survivre au jeûne du Carême . [89] C’est devenu un festival public en 1751 et est maintenant le deuxième plus grand festival de bière à Munich. [89] Starkbierfest est également connue sous le nom de « cinquième saison » et est célébrée dans les brasseries et les restaurants de la ville. [88]

Frühlingsfest

Avril et mai, Theresienwiese : [88] Tenue pendant deux semaines de fin avril à début mai, [88] Frühlingsfest célèbre le printemps et les nouvelles bières printanières locales, et est communément appelée la “petite sœur de l’Oktoberfest” . [90] Il y a deux tentes à bière, Hippodrom et Festhalle Bayernland, ainsi qu’un jardin à bière couvert , Münchner Weißbiergarten. [91] Il y a aussi des montagnes russes , des manèges , des toboggans et une grande roue . Les autres attractions du festival incluent un marché aux pucesle premier samedi du festival, un concours “Beer Queen”, un salon de Voitures anciennes le premier dimanche, un feu d’artifice tous les vendredis soirs et une “Journée des Traditions” le dernier jour. [91]

Auer Dult

Mai, août et octobre, Mariahilfplatz : [88] Auer Dult est la plus grande braderie d’Europe , avec des foires de CE type remontant au 14ème siècle. [92] L’Auer Dult est un marché traditionnel avec 300 étals vendant de l’artisanat artisanal, des articles ménagers et des aliments locaux , et propose des manèges de carnaval pour les enfants. Il s’est déroulé sur neuf jours chacun, trois fois par an. depuis 1905. [88] [92]

Kocherlball

Juillet, jardin anglais : [88] Traditionnellement, un bal pour les domestiques , les cuisiniers, les nounous et les autres membres du personnel de Munich, le Kocherlball, ou « bal du cuisinier » était une occasion pour les classes inférieures de prendre la matinée et de danser ensemble devant les familles. de leurs foyers se sont réveillés. [88] Il court maintenant entre 6 et 10 heures du matin le troisième dimanche en juillet à la tour chinoise dans le jardin anglais de Munich. [93]

Tollwood

Festival d’ hiver de Tollwood

Festival d’ hiver de Tollwood

July and December, Olympia Park:[94] For three weeks in July, and then three weeks in December, Tollwood showcases fine and performing arts with live music, circus acts, and several lanes of booths selling handmade crafts, as well as organic international cuisine.[88] According to the festival’s website, Tollwood’s goal is to promote culture and the environment, with the main themes of “tolerance, internationality, and openness”.[95] To promote these ideals, 70% of all Tollwood events and attractions are free.[95]

Oktoberfest

September and October, Theresienwiese:[88] The largest beer festival in the world, Munich’s Oktoberfest runs for 16–18 days from the end of September through early October.[96] Oktoberfest is a celebration of the wedding of Bavarian Crown Prince Ludwig to Princess Therese of Saxony-Hildburghausen which took place on 12 October 1810.[97] In the last 200 years the festival has grown to span 85 acres and now welcomes over 6 million visitors every year.[96] There are 14 beer tents which together can seat 119,000 attendees at a time,[96] and serve beer from the six major breweries of Munich: Augustiner, Hacker-Pschorr, Löwenbräu, Paulaner, Spaten and Staatliches Hofbräuhaus.[97] Over 7 million liters of beer are consumed at each Oktoberfest.[96] There are also over 100 rides ranging from bumper cars to full-sized roller coasters, as well as the more traditional Ferris wheels and swings.[97] Food can be bought in each tent, as well as at various stalls throughout the fairgrounds. Oktoberfest hosts 144 caterers and employees 13,000 people.[96]

Christkindlmarkt

November and December, city-wide:[88] Munich’s Christmas Markets, or Christkindlmärkte, are held throughout the city from late November until Christmas Eve, the largest spanning the Marienplatz and surrounding streets.[88] There are hundreds of stalls selling handmade goods, Christmas ornaments and decorations, and Bavarian Christmas foods including pastries, roasted nuts, and gluwein.[88]

Mini-Munich

Late-July to mid-August, city-wide: Mini-Munich provides kids ages 7–15 with the opportunity to participate in a Spielstadt, the German term for a miniature city composed almost entirely of children. Funded by Kultur & Spielraum, this play city is run by young Germans performing the same duties as adults, including voting in city council, paying taxes, and building businesses. The experimental game was invented in Munich in the 1970s and has since spread to other countries like Egypt and China.

Coopers’ Dance

The Coopers’ Dance (German: Schäfflertanz) is a guild dance of coopers originally started in Munich. Since early 1800s the custom spread via journeymen in it is now a common tradition over the Old Bavaria region. The dance was supposed to be held every 7 years.[98]

Cultural history trails and bicycle routes

Since 2001, historically interesting places in Munich can be explored via the cultural history trails (KulturGeschichtsPfade). Sign-posted cycle routes are the Outer Äußere Radlring (outer cycle route) and the RadlRing München.[99]

Cuisine and culinary specialities

Weisswurst with sweet mustard and a pretzel

Weisswurst with sweet mustard and a pretzel

The Munich cuisine contributes to the Bavarian cuisine. Munich Weisswurst (“white sausage”, German: Münchner Weißwurst) was invented here in 1857. It is a Munich speciality. Traditionally eaten only before noon – a tradition dating to a time before refrigerators – these morsels are often served with sweet mustard and freshly baked pretzels.

Munich offers 11 restaurants that have been awarded one or more Michelin stars in the Michelin Guide of 2021.[100]

Beers and breweries

Helles beer

Helles beer

Augustiner brewery

Augustiner brewery

Munich is known for its breweries and the Weissbier (or Weißbier / Weizenbier, wheat beer) is a speciality from Bavaria. Helles, a pale lager with a translucent gold colour is the most popular Munich beer today, although it’s not old (only introduced in 1895) and is the result of a change in beer tastes. Helles has largely replaced Munich’s dark beer, Dunkles, which gets its colour from roasted malt. It was the typical beer in Munich in the 19th century, but it is now more of a speciality. Starkbier is the strongest Munich beer, with 6%–9% alcohol content. It is dark amber in colour and has a heavy malty taste. It is available and is sold particularly during the Lenten Starkbierzeit (strong beer season), which begins on or before St. Joseph’s Day (19 March). The beer served at Oktoberfest is a special type of Märzen beer with a higher alcohol content than regular Helles.

There are countless Wirtshäuser (traditional Bavarian ale houses/restaurants) all over the city area, many of which also have small outside areas. Biergärten (beer gardens) are popular fixtures of Munich’s gastronomic landscape. They are central to the city’s culture and serve as a kind of melting pot for members of all walks of life, for locals, expatriates and tourists alike. It is allowed to bring one’s own food to a beer garden, however, it is forbidden to bring one’s own drinks. There are many smaller beer gardens and around twenty major ones, providing at least a thousand seats, with four of the largest in the Englischer Garten: Chinesischer Turm (Munich’s second-largest beer garden with 7,000 seats), Seehaus, Hirschau and Aumeister. Nockherberg, Hofbräukeller (not to be confused with the Hofbräuhaus) and Löwenbräukeller are other beer gardens. Hirschgarten is the largest beer garden in the world, with 8,000 seats.

There are six main breweries in Munich: Augustiner-Bräu, Hacker-Pschorr, Hofbräu, Löwenbräu, Paulaner and Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu (separate brands Spaten and Franziskaner, the latter of which mainly for Weissbier).

Also much consumed, though not from Munich and thus without the right to have a tent at the Oktoberfest, are Tegernseer and Schneider Weisse, the latter of which has a major beer hall in Munich. Smaller breweries are becoming more prevalent in Munich, such as Giesinger Bräu.[101] However, these breweries do not have tents at Oktoberfest.

Circus

The Circus Krone based in Munich is one of the largest circuses in Europe.[102] It was the first and still is one of only a few in Western Europe to also occupy a building of its own.

Nightlife

The party ship Alte Utting

The party ship Alte Utting

Nightlife in Munich is located mostly in the city centre (Altstadt-Lehel) and the boroughs Maxvorstadt, Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt, Au-Haidhausen and Schwabing. Between Sendlinger Tor and Maximiliansplatz lies the so-called Feierbanane (party banana), a roughly banana-shaped unofficial party zone spanning 1.3 km (0.8 mi) along Sonnenstraße, characterised by a high concentration of clubs, bars and restaurants. The Feierbanane has become the mainstream focus of Munich’s nightlife and tends to become crowded, especially at weekends. It has also been the subject of some debate among city officials because of alcohol-related security issues and the party zone’s general impact on local residents as well as day-time businesses.

Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt’s two main quarters, Gärtnerplatzviertel and Glockenbachviertel, are both considered decidedly less mainstream than most other nightlife hotspots in the city and are renowned for their many hip and laid back bars and clubs as well as for being Munich’s main centres of gay culture. On warm spring or summer nights, hundreds of young people gather at Gärtnerplatz to relax, talk with friends and drink beer.

Bahnwärter Thiel

Bahnwärter Thiel

Maxvorstadt has many smaller bars that are especially popular with university students, whereas Schwabing, once Munich’s first and foremost party district with legendary clubs such as Big Apple, PN, Domicile, Hot Club, Piper Club, Tiffany, Germany’s first large-scale disco Blow Up and the underwater nightclub Yellow Submarine,[86] as well as many bars such as Schwabinger 7 or Schwabinger Podium, has lost much of its nightlife activity in the last decades, mainly due to gentrification and the resulting high rents. It has become the city’s most coveted and expensive residential district, attracting affluent citizens with little interest in partying.

Since the mid-1990s, the Kunstpark Ost and its successor Kultfabrik, a former industrial complex that was converted to a large party area near München Ostbahnhof in Berg am Laim, hosted more than 30 clubs and was especially popular among younger people and residents of the metropolitan area surrounding Munich.[103] The Kultfabrik was closed at the end of the year 2015 to convert the area into a residential and office area. Apart from the Kultfarbik and the smaller Optimolwerke, there is a wide variety of establishments in the urban parts of nearby Haidhausen. Before the Kunstpark Ost, there had already been an accumulation of internationally known nightclubs in the remains of the abandoned former Munich-Riem Airport.

Munich nightlife tends to change dramatically and quickly. Establishments open and close every year, and due to gentrification and the overheated housing market many survive only a few years, while others last longer. Beyond the already mentioned venues of the 1960s and 1970s, nightclubs with international recognition in recent history included Tanzlokal Größenwahn, Atomic Cafe and the techno clubs Babalu, Ultraschall, KW – Das Heizkraftwerk, Natraj Temple and MMA Club (Mixed Munich Arts).[104] From 1995 to 2001, Munich was also home to the Union Move, one of the largest technoparades in Germany.

Blitz Club

Blitz Club

Munich has two directly connected gay quarters, which basically can be seen as one: Gärtnerplatzviertel and Glockenbachviertel, both part of the Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt district. Freddie Mercury had an apartment near the Gärtnerplatz and transsexual icon Romy Haag had a club in the city centre for many years.

Munich has the highest density of music venues of any German city, followed by Hamburg, Cologne and Berlin.[105][106] Within the city’s limits there are more than 100 nightclubs and thousands of bars and restaurants.[107][108]

Some notable nightclubs are: popular techno clubs are Blitz Club, Harry Klein, Rote Sonne, Bahnwärter Thiel, Bob Beaman, Pimpernel, Charlie and Palais. Popular mixed music clubs are Call me Drella, Cord, Wannda Circus, Tonhalle, Backstage, Muffathalle, Ampere, Pacha, P1, Zenith, Minna Thiel and the party ship Alte Utting. Some notable bars (pubs are located all over the city) are Charles Schumann’s Cocktail Bar, Havana Club, Sehnsucht, Bar Centrale, Ksar, Holy Home, Eat the Rich, Negroni, Die Goldene Bar and Bei Otto (a bavarian-style pub).

Education

Colleges and universities

Main building of the LMU