Sécurité de la couche de transport

Transport Layer Security ( TLS ), le successeur de Secure Sockets Layer ( SSL ), désormais obsolète, est un protocole cryptographique conçu pour assurer la sécurité des communications sur un réseau informatique. Le protocole est largement utilisé dans des applications telles que la messagerie électronique , la messagerie instantanée et la voix sur IP , mais son utilisation pour sécuriser HTTPS reste la plus visible publiquement.

Le protocole TLS vise principalement à assurer la cryptographie , y compris la confidentialité (confidentialité), l’intégrité et l’authenticité grâce à l’utilisation de certificats , entre deux ou plusieurs applications informatiques communicantes. Il s’exécute dans la couche application et est lui-même composé de deux couches : l’enregistrement TLS et les protocoles de prise de contact TLS .

TLS est une norme proposée par l’Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), définie pour la première fois en 1999, et la version actuelle est TLS 1.3, définie en août 2018. TLS s’appuie sur les spécifications SSL antérieures (1994, 1995, 1996) développées par Netscape Communications pour ajoutant le protocole HTTPS à leur navigateur Web Navigator.

La description

Les applications client-serveur utilisent le protocole TLS pour communiquer sur un réseau d’une manière conçue pour empêcher l’écoute clandestine et la falsification .

Comme les applications peuvent communiquer avec ou sans TLS (ou SSL), il est nécessaire que le client demande au serveur d’établir une connexion TLS. [1] L’un des principaux moyens d’y parvenir consiste à utiliser un numéro de port différent pour les connexions TLS. Par exemple, le port 80 est généralement utilisé pour le trafic HTTP non chiffré tandis que le port 443 est le port commun utilisé pour le trafic HTTPS chiffré. Un autre mécanisme consiste pour le client à faire une demande spécifique au protocole au serveur pour basculer la connexion vers TLS ; par exemple, en faisant une requête STARTTLS lors de l’utilisation des protocoles mail et news .

Une fois que le client et le serveur ont convenu d’utiliser TLS, ils négocient une connexion avec état en utilisant une procédure d’ établissement de liaison . [2] Les protocoles utilisent une poignée de main avec un chiffrement asymétrique pour établir non seulement les paramètres de chiffrement, mais également une clé partagée spécifique à la session avec laquelle la communication ultérieure est chiffrée à l’aide d’un chiffrement symétrique . Au cours de cette poignée de main, le client et le serveur s’accordent sur différents paramètres utilisés pour établir la sécurité de la connexion :

- La poignée de main commence lorsqu’un client se connecte à un serveur compatible TLS demandant une connexion sécurisée et que le client présente une liste des suites de chiffrement prises en charge ( chiffres et fonctions de hachage ).

- Dans cette liste, le serveur choisit une fonction de chiffrement et de hachage qu’il prend également en charge et informe le client de la décision.

- Le serveur fournit alors généralement une identification sous la forme d’un certificat numérique . Le certificat contient le nom du serveur , l’ autorité de certification (CA) de confiance qui garantit l’authenticité du certificat et la clé de cryptage publique du serveur.

- Le client confirme la validité du certificat avant de poursuivre.

- Pour générer les clés de session utilisées pour la connexion sécurisée, le client soit :

- chiffre un nombre aléatoire ( PreMasterSecret ) avec la clé publique du serveur et envoie le résultat au serveur (que seul le serveur doit pouvoir déchiffrer avec sa clé privée) ; les deux parties utilisent ensuite le nombre aléatoire pour générer une clé de session unique pour le chiffrement et le déchiffrement ultérieurs des données pendant la session

- utilise l’échange de clés Diffie-Hellman pour générer en toute sécurité une clé de session aléatoire et unique pour le chiffrement et le déchiffrement qui a la propriété supplémentaire de secret de transmission : si la clé privée du serveur est divulguée à l’avenir, elle ne peut pas être utilisée pour déchiffrer la session en cours, même si la session est interceptée et enregistrée par un tiers.

Ceci conclut la poignée de main et commence la connexion sécurisée, qui est chiffrée et déchiffrée avec la clé de session jusqu’à ce que la connexion se ferme. Si l’une des étapes ci-dessus échoue, la négociation TLS échoue et la connexion n’est pas créée.

TLS et SSL ne s’intègrent parfaitement dans aucune couche unique du modèle OSI ou du modèle TCP/IP . [3] [4] TLS s’exécute “au-dessus d’un protocole de transport fiable (par exemple, TCP)” [5] , ce qui impliquerait qu’il se trouve au-dessus de la couche de transport . Il sert de chiffrement aux couches supérieures, ce qui est normalement la fonction de la couche de présentation . Cependant, les applications utilisent généralement TLS comme s’il s’agissait d’une couche de transport, [3] [4] même si les applications utilisant TLS doivent contrôler activement l’initiation des poignées de main TLS et la gestion des certificats d’authentification échangés. [5]

Lorsqu’elles sont sécurisées par TLS, les connexions entre un client (par exemple, un navigateur Web) et un serveur (par exemple, wikipedia.org) doivent avoir une ou plusieurs des propriétés suivantes :

- La connexion est privée (ou sécurisée ) car un algorithme à clé symétrique est utilisé pour chiffrer les données transmises. Les clés de ce chiffrement symétrique sont générées de manière unique pour chaque connexion et sont basées sur un secret partagé qui a été négocié au début de la session. Le serveur et le client négocient les détails de l’algorithme de chiffrement et des clés cryptographiques à utiliser avant la transmission du premier octet de données (voir ci-dessous). La négociation d’un secret partagé est à la fois sécurisée (le secret négocié est inaccessible aux oreilles indiscrètes et ne peut être obtenu, même par un attaquant qui se place au milieu de la connexion) et fiable (aucun attaquant ne peut modifier les communications pendant la négociation sans être détecté).

- L’identité des parties communicantes peut être authentifiée à l’ aide de la cryptographie à clé publique . Cette authentification est obligatoire pour le serveur et facultative pour le client. [6]

- La connexion est fiable car chaque message transmis comprend une vérification de l’intégrité du message à l’aide d’un code d’authentification de message pour empêcher la perte ou l’altération non détectée des données pendant la transmission. [7] : 3

En plus de ce qui précède, une configuration minutieuse de TLS peut fournir des propriétés supplémentaires liées à la confidentialité, telles que le secret de transmission , garantissant que toute divulgation future de clés de chiffrement ne peut pas être utilisée pour déchiffrer des communications TLS enregistrées dans le passé.

TLS prend en charge de nombreuses méthodes différentes pour échanger des clés, chiffrer des données et authentifier l’intégrité des messages. Par conséquent, la configuration sécurisée de TLS implique de nombreux paramètres configurables, et tous les choix ne fournissent pas toutes les propriétés liées à la confidentialité décrites dans la liste ci-dessus (voir les tableaux ci-dessous § Échange de clé , § Sécurité du chiffrement et § Intégrité des données ).

Des tentatives ont été faites pour subvertir certains aspects de la sécurité des communications que TLS cherche à fournir, et le protocole a été révisé à plusieurs reprises pour faire face à ces menaces de sécurité. Les développeurs de navigateurs Web ont révisé à plusieurs reprises leurs produits pour se défendre contre les faiblesses de sécurité potentielles après leur découverte (voir l’historique de prise en charge TLS/SSL des navigateurs Web).

Histoire et développement

| Protocole | Publié | Statut |

|---|---|---|

| SSL 1.0 | Inédit | Inédit |

| SSL 2.0 | 1995 | Obsolète en 2011 ( RFC 6176 ) |

| SSL 3.0 | 1996 | Obsolète en 2015 ( RFC 7568 ) |

| TLS 1.0 | 1999 | Obsolète en 2021 ( RFC 8996 ) [8] [9] [10] |

| TLS 1.1 | 2006 | Obsolète en 2021 ( RFC 8996 ) [8] [9] [10] |

| TLS 1.2 | 2008 | |

| TLS 1.3 | 2018 |

Système de réseau de données sécurisé

Le protocole TLS (Transport Layer Security Protocol), ainsi que plusieurs autres plates-formes de sécurité réseau de base, ont été développés dans le cadre d’une initiative conjointe lancée en août 1986 entre la National Security Agency, le National Bureau of Standards, la Defense Communications Agency et douze communications et sociétés informatiques qui ont lancé un projet spécial appelé Secure Data Network System (SDNS). [11]Le programme a été décrit en septembre 1987 lors de la 10e Conférence nationale sur la sécurité informatique dans un ensemble complet d’articles publiés. Le programme de recherche innovant s’est concentré sur la conception de la prochaine génération de réseaux de communication informatique sécurisés et de spécifications de produits à mettre en œuvre pour des applications sur des internets publics et privés. Il était destiné à compléter les nouvelles normes Internet OSI qui émergent rapidement, à la fois dans les profils GOSIP du gouvernement américain et dans l’énorme effort Internet ITU-ISO JTC1 au niveau international. Connu à l’origine sous le nom de protocole SP4, il a été renommé TLS puis publié en 1995 en tant que norme internationale ITU-T X.274 | ISO/CEI 10736:1995.

Programmation réseau sécurisée

Les premiers efforts de recherche vers la sécurité de la couche de transport comprenaient l’ interface de programmation d’application (API) Secure Network Programming (SNP) , qui en 1993 a exploré l’approche d’avoir une API de couche de transport sécurisée ressemblant étroitement aux sockets Berkeley , pour faciliter la mise à niveau des applications réseau préexistantes avec la sécurité. mesures. [12]

SSL 1.0, 2.0 et 3.0

Netscape a développé les protocoles SSL originaux, et Taher Elgamal , scientifique en chef chez Netscape Communications de 1995 à 1998, a été décrit comme le “père de SSL”. [13] [14] [15] [16]SSL version 1.0 n’a jamais été rendu public en raison de graves failles de sécurité dans le protocole. La version 2.0, après sa sortie en février 1995, s’est rapidement révélée contenir un certain nombre de failles de sécurité et de convivialité. Il utilisait les mêmes clés cryptographiques pour l’authentification et le chiffrement des messages. Il avait une construction MAC faible qui utilisait la fonction de hachage MD5 avec un préfixe secret, le rendant vulnérable aux attaques d’extension de longueur. Et il n’offrait aucune protection ni pour la poignée de main d’ouverture ni pour la fermeture d’un message explicite, ce qui signifiait que les attaques de l’homme du milieu pouvaient passer inaperçues. De plus, SSL 2.0 supposait un service unique et un certificat de domaine fixe, en conflit avec la fonctionnalité largement utilisée d’hébergement virtuel dans les serveurs Web, de sorte que la plupart des sites Web étaient effectivement empêchés d’utiliser SSL.

Ces failles ont nécessité la refonte complète du protocole vers SSL version 3.0. [17] [15] Sorti en 1996, il a été produit par Paul Kocher travaillant avec les ingénieurs de Netscape Phil Karlton et Alan Freier, avec une implémentation de référence par Christopher Allen et Tim Dierks de Consensus Development. Les nouvelles versions de SSL/TLS sont basées sur SSL 3.0. Le projet de 1996 de SSL 3.0 a été publié par l’IETF en tant que document historique dans la RFC 6101 .

SSL 2.0 a été déprécié en 2011 par RFC 6176 . En 2014, SSL 3.0 s’est avéré vulnérable à l’ attaque POODLE qui affecte tous les chiffrements par blocs dans SSL ; RC4 , le seul chiffrement non-bloc pris en charge par SSL 3.0, est également vraisemblablement cassé tel qu’il est utilisé dans SSL 3.0. [18] SSL 3.0 a été déprécié en juin 2015 par la RFC 7568 .

TLS 1.0

TLS 1.0 a été défini pour la première fois dans la RFC 2246 en janvier 1999 comme une mise à niveau de SSL version 3.0 et écrit par Christopher Allen et Tim Dierks de Consensus Development. Comme indiqué dans la RFC, “les différences entre ce protocole et SSL 3.0 ne sont pas dramatiques, mais elles sont suffisamment importantes pour empêcher l’interopérabilité entre TLS 1.0 et SSL 3.0”. Tim Dierks a écrit plus tard que ces changements, et le changement de nom de “SSL” en “TLS”, étaient un geste pour sauver la face de Microsoft, “donc il ne semblerait pas que l’IETF ne fasse qu’approuver le protocole de Netscape”. [19]

Le Conseil PCI a suggéré que les organisations migrent de TLS 1.0 vers TLS 1.1 ou supérieur avant le 30 juin 2018. [20] [21] En octobre 2018, Apple , Google , Microsoft et Mozilla ont annoncé conjointement qu’ils rendraient obsolètes TLS 1.0 et 1.1 en mars. 2020. [8]

TLS 1.1

TLS 1.1 a été défini dans la RFC 4346 en avril 2006. [22] Il s’agit d’une mise à jour de TLS version 1.0. Les différences significatives dans cette version incluent :

- Protection supplémentaire contre les attaques par chaînage de blocs de chiffrement (CBC).

- Le vecteur d’initialisation implicite (IV) a été remplacé par un IV explicite.

- Modification de la gestion des erreurs de remplissage .

- Prise en charge de l’ enregistrement IANA des paramètres. [23] : 2

La prise en charge des versions 1.0 et 1.1 de TLS a été largement dépréciée par les sites Web vers 2020, désactivant l’accès aux versions de Firefox avant 24 et aux navigateurs basés sur Chromium avant 29. [24] [25] [26]

TLS 1.2

TLS 1.2 a été défini dans la RFC 5246 en août 2008. Il est basé sur la spécification TLS 1.1 antérieure. Les principales différences incluent :

- La combinaison MD5 – SHA-1 dans la fonction pseudo -aléatoire (PRF) a été remplacée par SHA-256 , avec une option pour utiliser les PRF spécifiées par la suite de chiffrement .

- La combinaison MD5–SHA-1 dans le hachage de message fini a été remplacée par SHA-256, avec une option pour utiliser des algorithmes de hachage spécifiques à la suite de chiffrement. Cependant, la taille du hachage dans le message fini doit toujours être d’au moins 96 bits . [27]

- La combinaison MD5–SHA-1 dans l’élément signé numériquement a été remplacée par un seul hachage négocié lors de la poignée de main , qui est par défaut SHA-1.

- Amélioration de la capacité du client et du serveur à spécifier les hachages et les algorithmes de signature qu’ils acceptent.

- Extension de la prise en charge des chiffrements de chiffrement authentifiés , utilisés principalement pour le mode Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) et le mode CCM du chiffrement Advanced Encryption Standard (AES).

- La définition des extensions TLS et les suites de chiffrement AES ont été ajoutées. [23] : 2

Toutes les versions de TLS ont été affinées dans la RFC 6176 en mars 2011, supprimant leur rétrocompatibilité avec SSL de sorte que les sessions TLS ne négocient jamais l’utilisation de la version 2.0 de Secure Sockets Layer (SSL).

TLS 1.3

TLS 1.3 a été défini dans la RFC 8446 en août 2018. Il est basé sur la spécification TLS 1.2 antérieure. Les principales différences par rapport à TLS 1.2 incluent : [28]

- Séparer les algorithmes d’accord de clé et d’authentification des suites de chiffrement

- Suppression de la prise en charge des courbes elliptiques nommées faibles et moins utilisées

- Suppression de la prise en charge des fonctions de hachage cryptographique MD5 et SHA-224

- Exiger des signatures numériques même lorsqu’une configuration précédente est utilisée

- Intégration de HKDF et de la proposition DH semi-éphémère

- Remplacement de la reprise par PSK et tickets

- Prise en charge des poignées de main 1- RTT et prise en charge initiale de 0- RTT

- Mandater le secret de transmission parfait , au moyen de l’utilisation de clés éphémères lors de l’accord de clé (EC) DH

- Suppression de la prise en charge de nombreuses fonctionnalités non sécurisées ou obsolètes, notamment la compression , la renégociation, les chiffrements non AEAD , l’échange de clés non PFS (parmi lesquels les échanges de clés RSA statiques et DH statiques ), les groupes DHE personnalisés , la négociation du format de point EC, le protocole Change Cipher Spec, Heure UNIX du message Hello et entrée AD du champ de longueur dans les chiffrements AEAD

- Interdire la négociation SSL ou RC4 pour la rétrocompatibilité

- Intégration de l’utilisation du hachage de session

- Dépréciation de l’utilisation du numéro de version de la couche d’enregistrement et gel du numéro pour une meilleure rétrocompatibilité

- Déplacer certains détails d’algorithme liés à la sécurité d’une annexe à la spécification et reléguer ClientKeyShare à une annexe

- Ajout du chiffrement de flux ChaCha20 avec le code d’authentification de message Poly1305

- Ajout des algorithmes de signature numérique Ed25519 et Ed448

- Ajout des protocoles d’échange de clés X25519 et X448

- Ajout de la prise en charge de l’envoi de plusieurs réponses OCSP

- Chiffrement de tous les messages de poignée de main après le ServerHello

Network Security Services (NSS), la bibliothèque de cryptographie développée par Mozilla et utilisée par son navigateur Web Firefox , a activé TLS 1.3 par défaut en février 2017. [29] La prise en charge de TLS 1.3 a ensuite été ajoutée — mais en raison de problèmes de compatibilité pour un petit nombre de utilisateurs, pas automatiquement activés [30] — à Firefox 52.0 , sorti en mars 2017. TLS 1.3 a été activé par défaut en mai 2018 avec la sortie de Firefox 60.0 . [31]

Google Chrome a défini TLS 1.3 comme version par défaut pendant une courte période en 2017. Il l’a ensuite supprimé par défaut, en raison de boîtiers de médiation incompatibles tels que les proxies Web Blue Coat . [32]

Lors de l’IETF 100 Hackathon , qui s’est déroulé à Singapour en 2017, le groupe TLS a travaillé sur l’adaptation d’applications open source pour utiliser TLS 1.3. [33] [34] Le groupe TLS était composé d’individus du Japon, du Royaume-Uni et de Maurice via l’équipe cyberstorm.mu. [34] Ce travail a été poursuivi dans le Hackathon IETF 101 à Londres , [35] et le Hackathon IETF 102 à Montréal. [36]

wolfSSL a permis l’utilisation de TLS 1.3 à partir de la version 3.11.1 , publiée en mai 2017 . ainsi que de nombreuses versions plus anciennes. Une série de blogs ont été publiés sur la différence de performances entre TLS 1.2 et 1.3. [39]

DansSeptembre 2018, le projet populaire OpenSSL a publié la version 1.1.1 de sa bibliothèque, dans laquelle la prise en charge de TLS 1.3 était “la nouvelle fonctionnalité phare”. [40]

La prise en charge de TLS 1.3 a été ajoutée pour la première fois à SChannel avec Windows 11 et Windows Server 2022 . [41]

Sécurité des transports d’entreprise

L’ Electronic Frontier Foundation a fait l’ éloge de TLS 1.3 et s’est dite préoccupée par la variante de protocole Enterprise Transport Security (ETS) qui désactive intentionnellement d’importantes mesures de sécurité dans TLS 1.3. [42] Initialement appelé Enterprise TLS (eTLS), ETS est une norme publiée connue sous le nom de « ETSI TS103523-3 », « Middlebox Security Protocol, Part3 : Enterprise Transport Security ». Il est destiné à être utilisé entièrement dans des réseaux propriétaires tels que des systèmes bancaires. ETS ne prend pas en charge la confidentialité persistante afin de permettre aux organisations tierces connectées aux réseaux propriétaires de pouvoir utiliser leur clé privée pour surveiller le trafic réseau afin de détecter les logiciels malveillants et de faciliter la réalisation d’audits. [43] [44]Malgré les avantages revendiqués, l’EFF a averti que la perte du secret de transmission pourrait faciliter l’exposition des données tout en affirmant qu’il existe de meilleures façons d’analyser le trafic.

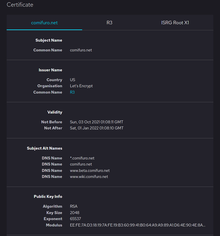

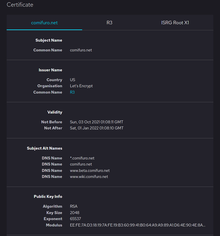

Certificats numériques

Exemple de site web avec certificat numérique

Exemple de site web avec certificat numérique

Un certificat numérique certifie la propriété d’une clé publique par le sujet nommé du certificat et indique certaines utilisations attendues de cette clé. Cela permet à d’autres (parties utilisatrices) de s’appuyer sur des signatures ou sur des affirmations faites par la clé privée qui correspond à la clé publique certifiée. Les magasins de clés et les magasins de confiance peuvent être dans différents formats, tels que .pem, .crt, .pfx et .jks.

Autorités de certification

TLS s’appuie généralement sur un ensemble d’autorités de certification tierces de confiance pour établir l’authenticité des certificats. La confiance est généralement ancrée dans une liste de certificats distribués avec un logiciel d’agent utilisateur [45] et peut être modifiée par la partie utilisatrice.

Selon Netcraft , qui surveille les certificats TLS actifs, l’autorité de certification (CA) leader du marché est Symantec depuis le début de leur enquête (ou VeriSign avant que l’unité commerciale des services d’authentification ne soit achetée par Symantec). En 2015, Symantec représentait un peu moins d’un tiers de tous les certificats et 44 % des certificats valides utilisés par les 1 million de sites Web les plus fréquentés, selon Netcraft. [46] En 2017, Symantec a vendu son activité TLS/SSL à DigiCert. [47] Dans un rapport mis à jour, il a été montré qu’IdenTrust , DigiCert et Sectigo sont les 3 principales autorités de certification en termes de part de marché depuis mai 2019.[48]

En conséquence du choix des certificats X.509 , des autorités de certification et une infrastructure à clé publique sont nécessaires pour vérifier la relation entre un certificat et son propriétaire, ainsi que pour générer, signer et administrer la validité des certificats. Bien que cela puisse être plus pratique que de vérifier les identités via un réseau de confiance , les divulgations de surveillance de masse de 2013 ont fait savoir plus largement que les autorités de certification sont un point faible du point de vue de la sécurité, permettant des attaques de l’homme du milieu (MITM) si l’autorité de certification coopère (ou est compromise). [49] [50]

Algorithmes

Échange de clé ou accord de clé

Avant qu’un client et un serveur puissent commencer à échanger des informations protégées par TLS, ils doivent échanger ou convenir en toute sécurité d’une clé de chiffrement et d’un chiffrement à utiliser lors du chiffrement des données (voir § Chiffrement ). Parmi les méthodes utilisées pour l’échange/l’accord de clés figurent : les clés publiques et privées générées avec RSA (notées TLS_RSA dans le protocole de prise de contact TLS), Diffie–Hellman (TLS_DH), Diffie–Hellman éphémère (TLS_DHE), Diffie–Hellman à courbe elliptique ( TLS_ECDH), Diffie–Hellman à courbe elliptique éphémère (TLS_ECDHE), Diffie–Hellman anonyme (TLS_DH_anon), [7] clé pré-partagée (TLS_PSK) [51] et Secure Remote Password (TLS_SRP). [52]

Les méthodes d’accord de clé TLS_DH_anon et TLS_ECDH_anon n’authentifient pas le serveur ou l’utilisateur et sont donc rarement utilisées car elles sont vulnérables aux attaques de type ” man-in-the-middle” . Seuls TLS_DHE et TLS_ECDHE fournissent le secret de transmission .

Les certificats de clé publique utilisés pendant l’échange/l’accord varient également dans la taille des clés de chiffrement publiques/privées utilisées pendant l’échange et donc la robustesse de la sécurité fournie. En juillet 2013, Google a annoncé qu’il n’utiliserait plus de clés publiques de 1024 bits et passerait à la place à des clés de 2048 bits pour augmenter la sécurité du cryptage TLS qu’il fournit à ses utilisateurs car la force de cryptage est directement liée à la taille de la clé. . [53] [54]

| Algorithme | SSL 2.0 | SSL 3.0 | TLS 1.0 | TLS 1.1 | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Statut |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSA | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Défini pour TLS 1.2 dans les RFC |

| DH – RSA | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | |

| DHE – RSA ( secret de transmission ) | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | |

| ECDH – RSA | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | |

| ECDHE – RSA (secret transmis) | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | |

| DH – DSS | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | |

| DHE – DSS (secret de transmission) | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non [55] | |

| ECDH – ECDSA | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | |

| ECDHE – ECDSA (secret transmis) | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | |

| ECDH – EdDSA | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | |

| ECDHE – EdDSA (secret transmis) [56] | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | |

| PSK | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| PSK – RSA | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| DHE – PSK (secret de transmission) | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | |

| ECDHE – PSK (secret transmis) | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | |

| PRS | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| SRP – DSS | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| SRP – RSA | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| KerberosName | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| DH -ANON (non sécurisé) | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| ECDH -ANON (non sécurisé) | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | ||

| GOST R 34.10-94 / 34.10-2001 [57] | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Proposé dans les brouillons RFC |

Chiffrer

| Chiffrer | Version du protocole | Statut | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taper | Algorithme | Force nominale (bits) | SSL 2.0 | SSL 3.0 [n 1] [n 2] [n 3] [n 4] |

TLS 1.0 [n 1] [n 3] |

TLS 1.1 [n 1] |

TLS 1.2 [n 1] |

TLS 1.3 | |

| Chiffrement par bloc avec mode de fonctionnement |

MCG AES [58] [n 5] | 256, 128 | N / A | N / A | N / A | N / A | Sécurise | Sécurise | Défini pour TLS 1.2 dans les RFC |

| AES CCM [59] [n 5] | N / A | N / A | N / A | N / A | Sécurise | Sécurise | |||

| AES SRC [n 6] | N / A | Précaire | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | N / A | |||

| Camélia GCM [60] [n 5] | 256, 128 | N / A | N / A | N / A | N / A | Sécurise | N / A | ||

| Camélia CBC [61] [n 6] | N / A | Précaire | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | N / A | |||

| MCG ARIA [62] [n 5] | 256, 128 | N / A | N / A | N / A | N / A | Sécurise | N / A | ||

| ARIA CBC [62] [n 6] | N / A | N / A | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | N / A | |||

| SEED CTF [63] [n 6] | 128 | N / A | Précaire | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | Dépend des atténuations | N / A | ||

| 3DES EDE CBC [n 6] [n 7] | 112 [n 8] | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | ||

| GOST 28147-89 CNT [57] [n 7] | 256 | N / A | N / A | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | Défini dans la RFC 4357 | |

| IDÉE CBC [n 6] [n 7] [n 9] | 128 | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | N / A | Supprimé de TLS 1.2 | |

| DES CBC [n 6] [n 7] [n 9] | 0 56 | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | N / A | ||

| 0 40 [n 10] | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | N / A | N / A | Interdit dans TLS 1.1 et versions ultérieures | ||

| RC2 SRC [n 6] [n 7] | 0 40 [n 10] | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | N / A | N / A | ||

| Chiffrement de flux | ChaCha20 – Poly1305 [68] [n 5] | 256 | N / A | N / A | N / A | N / A | Sécurise | Sécurise | Défini pour TLS 1.2 dans les RFC |

| RC4 [n 11] | 128 | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | Interdit dans toutes les versions de TLS par RFC 7465 | |

| 0 40 [n 10] | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | N / A | N / A | |||

| Rien | Nul [n 12] | – | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | Précaire | N / A | Défini pour TLS 1.2 dans les RFC |

Remarques

- ^ a b c d RFC 5746 doit être implémenté pour corriger un défaut de renégociation qui autrement casserait ce protocole.

- ^ Si les bibliothèques implémentent les correctifs répertoriés dans RFC 5746 , cela viole la spécification SSL 3.0, que l’IETF ne peut pas modifier contrairement à TLS. La plupart des bibliothèques actuelles implémentent le correctif et ignorent la violation qui en résulte.

- ^ a b L’ attaque BEAST brise tous les chiffrements par blocs (chiffres CBC) utilisés dans SSL 3.0 et TLS 1.0 à moins qu’ils ne soient atténués par le client et/ou le serveur. Voir § Navigateurs Web .

- ^ L’ attaque POODLE brise tous les chiffrements par blocs (chiffres CBC) utilisés dans SSL 3.0 à moins qu’ils ne soient atténués par le client et/ou le serveur. Voir § Navigateurs Web .

- ^ a b c d e Les chiffrements AEAD (tels que GCM et CCM ) ne peuvent être utilisés que dans TLS 1.2 ou version ultérieure.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Les chiffrements CBC peuvent être attaqués avec l’ attaque Lucky Thirteen si la bibliothèque n’est pas écrite avec soin pour éliminer les canaux latéraux de synchronisation.

- ^ a b c d e L’ attaque Sweet32 brise les chiffrements par bloc avec une taille de bloc de 64 bits. [64]

- ^ Bien que la longueur de clé de 3DES soit de 168 bits, la force de sécurité effective de 3DES n’est que de 112 bits, [65] ce qui est inférieur au minimum recommandé de 128 bits. [66]

- ^ a b IDEA et DES ont été supprimés de TLS 1.2. [67]

- ^ a b c Des suites de chiffrement de 40 bits ont été intentionnellement conçues avec des longueurs de clé réduites pour se conformer aux réglementations américaines annulées depuis interdisant l’exportation de logiciels cryptographiques contenant certains algorithmes de chiffrement puissants (voir Exportation de cryptographie des États-Unis ). Ces suites faibles sont interdites dans TLS 1.1 et versions ultérieures.

- ^ L’utilisation de RC4 dans toutes les versions de TLS est interdite par la RFC 7465 (car les attaques RC4 affaiblissent ou cassent RC4 utilisé dans SSL/TLS).

- ^ Authentification uniquement, pas de cryptage.

Intégrité des données

Un code d’authentification de message (MAC) est utilisé pour l’intégrité des données. HMAC est utilisé pour le mode CBC des chiffrements par blocs. Le chiffrement authentifié (AEAD) tel que le mode GCM et le mode CCM utilise le MAC intégré à AEAD et n’utilise pas le HMAC . [69] PRF basé sur HMAC ou HKDF est utilisé pour la prise de contact TLS.

| Algorithme | SSL 2.0 | SSL 3.0 | TLS 1.0 | TLS 1.1 | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Statut |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMAC – MD5 | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Défini pour TLS 1.2 dans les RFC |

| HMAC – SHA1 | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | |

| HMAC – SHA256/384 | Non | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Non | |

| AEAD | Non | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | |

| GOST 28147-89 IMIT [57] | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Proposé dans les brouillons RFC | |

| GOST R 34.11-94 [57] | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui |

Candidatures et adoption

Dans la conception d’applications, TLS est généralement implémenté au-dessus des protocoles de la couche de transport, cryptant toutes les données liées au protocole de protocoles tels que HTTP , FTP , SMTP , NNTP et XMPP .

Historiquement, TLS a été utilisé principalement avec des protocoles de transport fiables tels que le protocole TCP ( Transmission Control Protocol ). Cependant, il a également été implémenté avec des protocoles de transport orientés datagramme, tels que le protocole de datagramme utilisateur (UDP) et le protocole de contrôle de congestion de datagramme (DCCP), dont l’utilisation a été normalisée indépendamment en utilisant le terme Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS) .

Sites Internet

L’une des principales utilisations de TLS consiste à sécuriser le trafic World Wide Web entre un site Web et un navigateur Web codé avec le protocole HTTP. Cette utilisation de TLS pour sécuriser le trafic HTTP constitue le protocole HTTPS . [70]

| Version du protocole | Prise en charge du site Web [71] | Sécurité [71] [72] |

|---|---|---|

| SSL 2.0 | 0,4 % | Précaire |

| SSL 3.0 | 3,0 % | Insécurisé [73] |

| TLS 1.0 | 43,8 % | Obsolète [8] [9] [10] |

| TLS 1.1 | 47,8 % | Obsolète [8] [9] [10] |

| TLS 1.2 | 99,6 % | Dépend du chiffrement [n 1] et des atténuations du client [n 2] |

| TLS 1.3 | 49,7 % | Sécurise |

Remarques

- ^ voir § Table de chiffrement ci-dessus

- ^ voir § Navigateurs Web etsections TLS/SSL

Navigateurs Web

Depuis avril 2016 [update], les dernières versions de tous les principaux navigateurs Web prennent en charge TLS 1.0, 1.1 et 1.2, et les ont activés par défaut. Cependant, tous les systèmes d’exploitation Microsoft pris en charge ne prennent pas en charge la dernière version d’IE. De plus, de nombreux systèmes d’exploitation Microsoft prennent actuellement en charge plusieurs versions d’IE, mais cela a changé selon la FAQ sur la politique de cycle de vie de la prise en charge d’Internet Explorer de Microsoft., “à compter du 12 janvier 2016, seule la version la plus récente d’Internet Explorer disponible pour un système d’exploitation pris en charge recevra une assistance technique et des mises à jour de sécurité.” La page continue ensuite en répertoriant la dernière version prise en charge d’IE à cette date pour chaque système d’exploitation. La prochaine date critique serait le moment où un système d’exploitation atteint la fin de la phase de vie, qui figure dans la fiche d’information sur le cycle de vie de Windows de Microsoft .

Les atténuations contre les attaques connues ne suffisent pas encore :

- Atténuations contre l’attaque POODLE : certains navigateurs empêchent déjà le repli vers SSL 3.0 ; cependant, cette atténuation doit être prise en charge non seulement par les clients, mais également par les serveurs. La désactivation de SSL 3.0 lui-même, la mise en œuvre du “fractionnement d’enregistrements anti-POODLE” ou le refus des chiffrements CBC dans SSL 3.0 sont nécessaires.

- Google Chrome : complet (TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV est implémenté depuis la version 33, le retour à SSL 3.0 est désactivé depuis la version 39, SSL 3.0 lui-même est désactivé par défaut depuis la version 40. Le support de SSL 3.0 lui-même a été abandonné depuis la version 44.)

- Mozilla Firefox : complet (le support de SSL 3.0 lui-même est abandonné depuis la version 39 . SSL 3.0 lui-même est désactivé par défaut et les retours vers SSL 3.0 sont désactivés depuis la version 34 , TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV est implémenté depuis la version 35. Dans ESR, SSL 3.0 lui-même est désactivé par par défaut et TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV est implémenté depuis ESR 31.3.)

- Internet Explorer : partiel (uniquement dans la version 11, SSL 3.0 est désactivé par défaut depuis avril 2015. Les versions 10 et antérieures sont toujours vulnérables contre POODLE.)

- Opera : complet (TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV est implémenté depuis la version 20, “anti-POODLE record splitting”, qui n’est efficace qu’avec l’implémentation côté client, est implémenté depuis la version 25, SSL 3.0 lui-même est désactivé par défaut depuis la version 27. Support de SSL 3.0 lui-même sera abandonné depuis la version 31.)

- Safari : complet (uniquement sur OS X 10.8 et versions ultérieures et iOS 8, les chiffrements CBC lors du retour à SSL 3.0 sont refusés, mais cela signifie qu’il utilisera RC4, ce qui n’est pas non plus recommandé. La prise en charge de SSL 3.0 lui-même est abandonnée sur OS X 10.11 et versions ultérieures et iOS 9.)

- Atténuation contre les attaques RC4 :

- Google Chrome a désactivé RC4 sauf en tant que solution de secours depuis la version 43. RC4 est désactivé depuis Chrome 48.

- Firefox a désactivé RC4 sauf en tant que solution de secours depuis la version 36. Firefox 44 a désactivé RC4 par défaut.

- Opera a désactivé RC4 sauf en tant que solution de secours depuis la version 30. RC4 est désactivé depuis Opera 35.

- Internet Explorer pour Windows 7 / Server 2008 R2 et pour Windows 8 / Server 2012 a défini la priorité de RC4 sur la plus basse et peut également désactiver RC4, sauf en tant que solution de secours via les paramètres de registre. Internet Explorer 11 Mobile 11 pour Windows Phone 8.1 désactive RC4 sauf comme solution de secours si aucun autre algorithme activé ne fonctionne. Edge et IE 11 désactivent complètement RC4 en août 2016.

- Atténuation contre l’attaque FREAK :

- Le navigateur Android inclus avec Android 4.0 et les versions antérieures est toujours vulnérable à l’attaque FREAK.

- Internet Explorer 11 Mobile est toujours vulnérable à l’attaque FREAK.

- Google Chrome, Internet Explorer (ordinateur de bureau), Safari (ordinateur de bureau et mobile) et Opera (mobile) ont mis en place des mesures d’atténuation FREAK.

- Mozilla Firefox sur toutes les plateformes et Google Chrome sur Windows n’ont pas été affectés par FREAK.

| Navigateur | Version | Plateformes | Protocoles SSL | Protocoles TLS | Prise en charge des certificats | Vulnérabilités corrigées [n 1] | Sélection du protocole par l’utilisateur [n 2] |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSL 2.0 (non sécurisé) | SSL 3.0 (non sécurisé) | TLS 1.0 (obsolète) | TLS 1.1 (obsolète) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | EV [n 3] [74] |

SHA-2 [75] |

ECDSA [76] |

BÊTE [n 4] | CRIMINALITÉ [n 5] | CANICHE (SSLv3) [n 6] | RC4 [n 7] | FRÉQUENCE [77] [78] | Embâcle | |||||

| Google Chrome ( Chrome pour Android ) [n 8] [n 9] |

1–9 | Windows (7+) macOS (10.11+) Linux Android (5.0+) iOS (12.2+) Chrome OS |

Désactivé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible SHA-2 [75] | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Non affecté [83] |

Vulnérable (HTTPS) |

Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |

| 10–20 | Non [84] | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible SHA-2 [75] | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Vulnérable (HTTPS/SPDY) |

Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 21 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible SHA-2 [75] | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué [85] |

Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 22–29 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Oui [86] | Non [86] [87] [88] [89] | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible SHA-2 [75] | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 30–32 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui [87] [88] [89] | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible SHA-2 [75] | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 33–37 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible SHA-2 [75] | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Partiellement atténué [n 12] |

Priorité la plus basse [92] [93] [94] |

Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 38, 39 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Partiellement atténué | Priorité la plus basse | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 40 | Non | Désactivé par défaut [91] [95] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué [n 13] |

Priorité la plus basse | Vulnérable (sauf Windows) |

Vulnérable | Oui [n 14] | |||

| 41, 42 | Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué | Priorité la plus basse | Atténué | Vulnérable | Oui [n 14] | |||

| 43 | Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué | Uniquement comme solution de repli [n 15] [96] |

Atténué | Vulnérable | Oui [n 14] | |||

| 44–47 | Non | Non [97] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Uniquement comme repli [n 15] |

Atténué | Atténué [98] | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 48, 49 | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | nécessite un système d’exploitation compatible ECC [76] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 50–53 | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 54–66 | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Désactivé par défaut (version brouillon) |

Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 67–69 | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui (version préliminaire) |

Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 70–83 | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 84–90 | Non | Non | Avertir par défaut | Avertir par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| 91–99 | Non | Non | Non [101] | Non [101] | Oui | Oui | Oui (ordinateur de bureau uniquement) |

Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [99] [100] | Atténué | Atténué | Temporaire [n 11] |

|||

| ESC 100 | 101 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Navigateur | Version | Plateformes | SSL 2.0 (non sécurisé) | SSL 3.0 (non sécurisé) | TLS 1.0 (obsolète) | TLS 1.1 (obsolète) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Certificat VE | Certificat SHA-2 | Certificat ECDSA | LA BÊTE | LA CRIMINALITÉ | CANICHE (SSLv3) | RC4 | MONSTRE | Embâcle | Sélection du protocole par l’utilisateur | |

| Microsoft Edge (basé sur Chromium) indépendant du système d’exploitation |

79–83 | Windows (7+) macOS (10.12+) Linux Android (4.4+) iOS (11.0+) |

Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | |

| 84–90 | Non | Non | Avertir par défaut | Avertir par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 91-99 | Non | Non | Non [102] | Non [102] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | |||

| ESC 100 | 101 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Navigateur | Version | Plateformes | SSL 2.0 (non sécurisé) | SSL 3.0 (non sécurisé) | TLS 1.0 (obsolète) | TLS 1.1 (obsolète) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Certificat VE | Certificat SHA-2 | Certificat ECDSA | LA BÊTE | LA CRIMINALITÉ | CANICHE (SSLv3) | RC4 | MONSTRE | Embâcle | Sélection du protocole par l’utilisateur | |

| Mozilla Firefox ( Firefox pour mobile ) [n 17] |

1.0, 1.5 | Windows (7+) macOS (10.12+) Linux Android (5.0+) iOS (11.4+) Firefox OS Maemo ESR uniquement pour : Windows (7+) macOS (10.12+) Linux |

Activé par défaut [103] |

Activé par défaut [103] |

Oui [103] | Non | Non | Non | Non | Oui [75] | Non | Non affecté [104] |

Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |

| 2 | Désactivé par défaut [103] [105] |

Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui [76] | Pas affecté | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 3–7 | Désactivé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 8–10 RSE 10 |

Non [105] | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 11–14 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Vulnérable (SPDY) [85] |

Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 15–22 RSE 17.0–17.0.10 |

Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| RSE 17.0.11 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Priorité la plus basse [106] [107] |

Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 23 | Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Désactivé par défaut [108] |

Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 24, 25.0.0 RSE 24.0–24.1.0 |

Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Désactivé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut [109] |

Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 25.0.1, 26 ESR 24.1.1 |

Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Désactivé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Priorité la plus basse [106] [107] |

Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 27–33 RSE 31.0–31.2 |

Non | Activé par défaut | Oui | Oui [110] [111] | Oui [112] [111] | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Vulnérable | Priorité la plus basse | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 34, 35 ESR 31.3–31.7 |

Non | Désactivé par défaut [113] [114] |

Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué [n 19] |

Priorité la plus basse | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 18] | |||

| RSE 31.8 | Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué | Priorité la plus basse | Pas affecté | Atténué [117] | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 36–38 RSE 38,0 |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué | Uniquement comme repli [n 15] [118] |

Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Oui [n 18] | |||

| RSE 38.1–38.8 | Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Atténué | Uniquement comme repli [n 15] |

Pas affecté | Atténué [117] | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 39–43 | Non | Non [119] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Uniquement comme repli [n 15] |

Pas affecté | Atténué [117] | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 44–48 RSE 45 |

Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] [120] [121] [122] [123] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 49–59 RSE 52 |

Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Désactivé par défaut (version brouillon) [124] |

Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 60–62 RSE 60 |

Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui (version préliminaire) |

Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 63–77 RSE 68 |

Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Oui [n 18] | |||

| 78–99 RSE 78 RSE 91,0–91,8 |

Non | Non | Désactivé par défaut [125] | Désactivé par défaut [125] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui | Pas affecté | Atténué | Pas affecté | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Pas affecté | Atténué | Oui [n 18] | |||

| RSE 91.9 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Navigateur | Version | Plateformes | SSL 2.0 (non sécurisé) | SSL 3.0 (non sécurisé) | TLS 1.0 (obsolète) | TLS 1.1 (obsolète) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Certificat VE | Certificat SHA-2 | Certificat ECDSA | LA BÊTE | LA CRIMINALITÉ | CANICHE (SSLv3) | RC4 | MONSTRE | Embâcle | Sélection du protocole par l’utilisateur | |

| Microsoft Internet Explorer (1–10) [n 20] |

1 fois | Windows 3.1 , 95 , NT , [n 21] [n 22] Mac OS 7 , 8 |

Pas de prise en charge SSL/TLS | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Pas de prise en charge SSL 3.0 ou TLS | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | N / A | |||||

| 3 | Oui | Oui [128] | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Inconnue | |||

| 4 , 5 , 6 | Windows 3.1 , 95 , 98 , NT , 2000 [n 21] [n 22] Mac OS 7.1 , 8 , X , Solaris , HP-UX |

Activé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut [128] |

Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Non | Vulnérable | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 6 | Windows XP [n 22] | Activé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut | Non | Non | Non | Non | Oui (depuis SP3) [n 23] [129] |

Non | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 7 , 8 | Désactivé par défaut [130] |

Activé par défaut | Oui [130] | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui (depuis SP3) [n 23] [129] |

Non | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Oui [n 10] | |||

| 6 | Serveur 2003 [n 22] | Activé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut | Non | Non | Non | Non | Oui (KB938397+KB968730) [n 23] [129] |

Non | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | ||

| 7 , 8 | Désactivé par défaut [130] |

Activé par défaut | Oui [130] | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui (KB938397+KB968730) [n 23] [129] |

Non | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | |||

| 7 , 8 , 9 | Windows Vista | Désactivé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Oui | Non | Non | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui [76] | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | ||

| 7 , 8 , 9 | Serveur 2008 | Désactivé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Oui | Désactivé par défaut [135] (KB4019276) |

Désactivé par défaut [135] (KB4019276) |

Non | Oui | Oui | Oui [76] | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Vulnérable | Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | ||

| 8 , 9 , 10 | Windows 7/8 Serveur 2008 R2 / 2012 _ | Désactivé par défaut | Activé par défaut | Oui | Désactivé par défaut [136] |

Désactivé par défaut [136] |

Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Vulnérable | Priorité la plus basse [137] [n 24] |

Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | ||

| Internet Explorer 11 [n 20] |

11 | Windows 7 Serveur 2008 R2 |

Désactivé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut [n 25] |

Oui | Oui [139] | Oui [139] | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué [n 25] |

Désactivé par défaut [143] | Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | |

| 11 [144] | Windows 8.1 | Désactivé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut [n 25] |

Oui | Oui [139] | Oui [139] | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué [n 25] |

Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué [133] |

Atténué [134] |

Oui [n 10] | ||

| Serveur 2012 Serveur 2012 R2 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Navigateur | Version | Plateformes | SSL 2.0 (non sécurisé) | SSL 3.0 (non sécurisé) | TLS 1.0 (obsolète) | TLS 1.1 (obsolète) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Certificat VE | Certificat SHA-2 | Certificat ECDSA | LA BÊTE | LA CRIMINALITÉ | CANICHE (SSLv3) | RC4 | MONSTRE | Embâcle | Sélection du protocole par l’utilisateur | |

| Microsoft Edge (12–18) (basé sur EdgeHTML) Client uniquement Internet Explorer 11 [n 20] |

11 | 12–13 | Windows 10 1507–1511 |

Désactivé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] |

| 11 | 14–18 (client uniquement) |

Windows 10 1607–2004 Windows Serveur (SAC) 1709–2004 |

Non [145] | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | |

| Internet Explorer 11 [n 20] |

11 | Windows 10 20H2 Windows Serveur (SAC) 20H2 |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | |

| 11 | Windows 10 21H1 |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 11 | Windows 10 21H2 |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 11 | Windows 11 | Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui [146] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| Internet Explorer 11 [n 20] Versions LTSC |

11 | Windows 10 LTSB 2015 (1507) |

Désactivé par défaut | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | |

| 11 | Windows 10 LTSB 2016 (1607) |

Non [145] | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 11 | Windows Server 2016 (LTSB / 1607) |

Non [145] | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 11 | Windows 10 LTSC 2019 (1809) Windows Server 2019 (LTSC / 1809) |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 11 | Windows 10 LTSC 2021 (21H2) |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Non | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| 11 | Windows Server 2022 (LTSC) |

Non | Désactivé par défaut | Oui | Oui | Oui | Oui [146] | Oui | Oui | Oui | Atténué | Pas affecté | Atténué | Désactivé par défaut [n 16] | Atténué | Atténué | Oui [n 10] | ||

| Navigateur | Version | Plateformes | SSL 2.0 (non sécurisé) | SSL 3.0 (non sécurisé) | TLS 1.0 (obsolète) | TLS 1.1 (obsolète) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | Certificat VE | Certificat SHA-2 | Certificat ECDSA | LA BÊTE | LA CRIMINALITÉ | CANICHE (SSLv3) | RC4 | MONSTRE | Embâcle | Sélection du protocole par l’utilisateur | |

| Microsoft Internet Explorer Mobile [n 20] |

7, 9 | Windows Phone 7, 7.5, 7.8 | Disabled by default [130] |

Enabled by default | Yes | No [citation needed] |

No [citation needed] |

No | No [citation needed] |

Yes | Yes[147] | Unknown | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Only with 3rd party tools[n 26] | |

| 10 | Windows Phone 8 | Disabled by default | Enabled by default | Yes | Disabled by default [149] |

Disabled by default [149] |

No | No [citation needed] |

Yes | Yes[150] | Mitigated | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Only with 3rd party tools[n 26] | ||

| 11 | Windows Phone 8.1 | Disabled by default | Enabled by default | Yes | Yes[151] | Yes[151] | No | No [citation needed] |

Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Vulnerable | Only as fallback [n 15][152][153] |

Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Only with 3rd party tools[n 26] | ||

| Microsoft Edge (13–15) (EdgeHTML-based) [n 27] |

13 | Windows 10 Mobile 1511 |

Disabled by default | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Mitigated | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |

| 14, 15 | Windows 10 Mobile 1607–1709 |

No[145] | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Mitigated | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| Browser | Version | Platforms | SSL 2.0 (insecure) | SSL 3.0 (insecure) | TLS 1.0 (deprecated) | TLS 1.1 (deprecated) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | EV certificate | SHA-2 certificate | ECDSA certificate | BEAST | CRIME | POODLE (SSLv3) | RC4 | FREAK | Logjam | Protocol selection by user | |

| Apple Safari [n 28] |

1 | Mac OS X 10.2, 10.3 | No[158] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | |

| 2–5 | Mac OS X 10.4, 10.5, Win XP | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | since v3.2 | No | No | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| 3–5 | Vista, Win 7 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | since v3.2 | No | Yes[147] | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| 4–6 | Mac OS X 10.6, 10.7 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes[75] | Yes[76] | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| 6 | OS X 10.8 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes[76] | Mitigated [n 29] |

Not affected | Mitigated [n 30] |

Vulnerable [n 30] |

Mitigated [164] |

Vulnerable | No | ||

| 7, 9 | OS X 10.9 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes[165] | Yes[165] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated [160] |

Not affected | Mitigated [n 30] |

Vulnerable [n 30] |

Mitigated [164] |

Vulnerable | No | ||

| 8–10 | OS X 10.10 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Mitigated [n 30] |

Lowest priority [166][n 30] |

Mitigated [164] |

Mitigated [167] |

No | ||

| 9–11 | OS X 10.11 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Lowest priority | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| 10–13 | macOS 10.12, 10.13 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| 12–14 | macOS 10.14 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (since macOS 10.14.4)[168] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| 13, 14 | 15 | macOS 10.15 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |

| 14 | 15 | macOS 11 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |

| 15 | macOS 12 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| Browser | Version | Platforms | SSL 2.0 (insecure) | SSL 3.0 (insecure) | TLS 1.0 (deprecated) | TLS 1.1 (deprecated) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | EV certificate | SHA-2 certificate | ECDSA certificate | BEAST | CRIME | POODLE (SSLv3) | RC4 | FREAK | Logjam | Protocol selection by user | |

| Apple Safari (mobile) [n 31] |

3 | iPhone OS 1, 2 | No[172] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | |

| 4, 5 | iPhone OS 3, iOS 4 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes[173] | Yes | since iOS 4[147] | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| 5, 6 | iOS 5, 6 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes[169] | Yes[169] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Vulnerable | Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| 7 | iOS 7 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes[174] | Mitigated [175] |

Not affected | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| 8 | iOS 8 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Mitigated [n 30] |

Lowest priority [176][n 30] |

Mitigated [177] |

Mitigated [178] |

No | ||

| 9 | iOS 9 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Lowest priority | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| 10, 11 | iOS 10, 11 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| 12 | iOS 12 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (since iOS 12.2)[168] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| 13, 14 | iOS 13, 14 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| iPadOS 13, 14 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | iOS 15 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitigated | Not affected | Not affected | Disabled by default[n 16] | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | ||

| iPadOS 15 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Browser | Version | Platforms | SSL 2.0 (insecure) | SSL 3.0 (insecure) | TLS 1.0 (deprecated) | TLS 1.1 (deprecated) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | EV [n 3] |

SHA-2 | ECDSA | BEAST[n 4] | CRIME[n 5] | POODLE (SSLv3)[n 6] | RC4[n 7] | FREAK[77][78] | Logjam | Protocol selection by user | |

| Google Android OS [179] |

Android 1.0–4.0.4 | No | Enabled by default | Yes | No | No | No | Unknown | Yes[75] | since 3.0[147][76] | Unknown | Unknown | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | ||

| Android 4.1–4.4.4 | No | Enabled by default | Yes | Disabled by default[180] | Disabled by default[180] | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | |||

| Android 5.0–5.0.2 | No | Enabled by default | Yes | Yes[180][181] | Yes[180][181] | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | No | |||

| Android 5.1–5.1.1 | No | Disabled by default [citation needed] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Only as fallback [n 15] |

Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 6.0–7.1.2 | No | Disabled by default [citation needed] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 8.0–8.1 | No | No [182] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 9 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 10 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 11 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 12 / 12L | No | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Android 13 | No | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Not affected | Disabled by default | Mitigated | Mitigated | No | |||

| Browser | Version | Platforms | SSL 2.0 (insecure) | SSL 3.0 (insecure) | TLS 1.0 (deprecated) | TLS 1.1 (deprecated) | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 | EV certificate | SHA-2 certificate | ECDSA certificate | BEAST | CRIME | POODLE (SSLv3) | RC4 | FREAK | Logjam | Protocol selection by user | |

| Color or Note | Significance | ||||||||||||||||||

| Browser version | Platform | ||||||||||||||||||

| Browser version | Operating system | Future release; under development | |||||||||||||||||

| Browser version | Operating system | Current latest release | |||||||||||||||||

| Browser version | Operating system | Former release; still supported | |||||||||||||||||

| Browser version | Operating system | Former release; long-term support still active, but will end in less than 12 months | |||||||||||||||||

| Browser version | Operating system | Former release; no longer supported | |||||||||||||||||

| n/a | Operating system | Mixed / Unspecified | |||||||||||||||||

| Operating system (Version+) | Minimum required operating system version (for supported versions of the browser) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operating system | No longer supported for this operating system |

Notes

- ^ Does the browser have mitigations or is not vulnerable for the known attacks. Note actual security depends on other factors such as negotiated cipher, encryption strength, etc. (see § Cipher table).

- ^ Whether a user or administrator can choose the protocols to be used or not. If yes, several attacks such as BEAST (vulnerable in SSL 3.0 and TLS 1.0) or POODLE (vulnerable in SSL 3.0) can be avoided.

- ^ a b Whether EV SSL and DV SSL (normal SSL) can be distinguished by indicators (green lock icon, green address bar, etc.) or not.

- ^ a b e.g. 1/n-1 record splitting.

- ^ a b e.g. Disabling header compression in HTTPS/SPDY.

- ^ a b

- Complete mitigations; disabling SSL 3.0 itself, “anti-POODLE record splitting”. “Anti-POODLE record splitting” is effective only with client-side implementation and valid according to the SSL 3.0 specification, however, it may also cause compatibility issues due to problems in server-side implementations.

- Partial mitigations; disabling fallback to SSL 3.0, TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV, disabling cipher suites with CBC mode of operation. If the server also supports TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV, the POODLE attack will fail against this combination of server and browser, but connections where the server does not support TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV and does support SSL 3.0 will still be vulnerable. If disabling cipher suites with CBC mode of operation in SSL 3.0, only cipher suites with RC4 are available, RC4 attacks become easier.

- When disabling SSL 3.0 manually, POODLE attack will fail.

- ^ a b

- Complete mitigation; disabling cipher suites with RC4.

- Partial mitigations to keeping compatibility with old systems; setting the priority of RC4 to lower.

- ^ Google Chrome (and Chromium) supports TLS 1.0, and TLS 1.1 from version 22 (it was added, then dropped from version 21). TLS 1.2 support has been added, then dropped from Chrome 29.[79][80][81]

- ^ Uses the TLS implementation provided by BoringSSL for Android, OS X, and Windows[82] or by NSS for Linux. Google is switching the TLS library used in Chrome to BoringSSL from NSS completely.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai configure enabling/disabling of each protocols via setting/option (menu name is dependent on browsers)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l configure the maximum and the minimum version of enabling protocols with command-line option

- ^ TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV is implemented.[90] Fallback to SSL 3.0 is disabled since version 39.[91]

- ^ In addition to TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV and disabling a fallback to SSL 3.0, SSL 3.0 itself is disabled by default.[91]

- ^ a b c configure the minimum version of enabling protocols via chrome://flags[95] (the maximum version can be configured with command-line option)

- ^ a b c d e f g Only when no cipher suites with other than RC4 is available, cipher suites with RC4 will be used as a fallback.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj All RC4 cipher suites are disabled by default.

- ^ Uses the TLS implementation provided by NSS. As of Firefox 22, Firefox supports only TLS 1.0 despite the bundled NSS supporting TLS 1.1. Since Firefox 23, TLS 1.1 can be enabled, but was not enabled by default due to issues. Firefox 24 has TLS 1.2 support disabled by default. TLS 1.1 and TLS 1.2 have been enabled by default in Firefox 27 release.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n configure the maximum and the minimum version of enabling protocols via about:config

- ^ SSL 3.0 itself is disabled by default.[113] In addition, fallback to SSL 3.0 is disabled since version 34,[115] and TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV is implemented since 35.0 and ESR 31.3.[113][116]

- ^ a b c d e f IE uses the TLS implementation of the Microsoft Windows operating system provided by the SChannel security support provider. TLS 1.1 and 1.2 are disabled by default until IE11.[126][127]

- ^ a b Windows NT 3.1 supports IE 1–2, Windows NT 3.5 supports IE 1–3, Windows NT 3.51 and Windows NT 4.0 supports IE 1–6

- ^ a b c d Windows XP as well as Server 2003 and older support only weak ciphers like 3DES and RC4 out of the box.[131] The weak ciphers of these SChannel version are not only used for IE, but also for other Microsoft products running on this OS, like Office or Windows Update. Only Windows Server 2003 can get a manual update to support AES ciphers by KB948963[132]

- ^ a b c d MS13-095 or MS14-049 for Windows Server 2003, Windows XP x64 and Windows XP SP3 (32-bit)

- ^ RC4 can be disabled except as a fallback (Only when no cipher suites with other than RC4 is available, cipher suites with RC4 will be used as a fallback.)[138]

- ^ a b c d Fallback to SSL 3.0 is sites blocked by default in Internet Explorer 11 for Protected Mode.[140][141] SSL 3.0 is disabled by default in Internet Explorer 11 since April 2015.[142]

- ^ a b c Could be disabled via registry editing but need 3rd Party tools to do this.[148]

- ^ Edge (formerly known as Project Spartan) is based on a fork of the Internet Explorer 11 rendering engine.

- ^ Safari uses the operating system implementation on Mac OS X, Windows (XP, Vista, 7)[154] with unknown version,[155] Safari 5 is the last version available for Windows. OS X 10.8 on have SecureTransport support for TLS 1.1 and 1.2[156] Qualys SSL report simulates Safari 5.1.9 connecting with TLS 1.0 not 1.1 or 1.2[157]

- ^ In September 2013, Apple implemented BEAST mitigation in OS X 10.8 (Mountain Lion), but it was not turned on by default, resulting in Safari still being theoretically vulnerable to the BEAST attack on that platform.[159][160] BEAST mitigation has been enabled by default from OS X 10.8.5 updated in February 2014.[161]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Because Apple removed support for all CBC protocols in SSL 3.0 to mitigate POODLE,[162][163] this leaves only RC4, which is also completely broken by the RC4 attacks in SSL 3.0.

- ^ Mobile Safari and third-party software utilizing the system UIWebView library use the iOS operating system implementation, which supports TLS 1.2 as of iOS 5.0.[169][170][171]

Libraries

Most SSL and TLS programming libraries are free and open source software.

- BoringSSL, a fork of OpenSSL for Chrome/Chromium and Android as well as other Google applications.

- Botan, a BSD-licensed cryptographic library written in C++.

- BSAFE Micro Edition Suite: a multi-platform implementation of TLS written in C using a FIPS-validated cryptographic module

- BSAFE SSL-J: a TLS library providing both a proprietary API and JSSE API, using FIPS-validated cryptographic module

- cryptlib: a portable open source cryptography library (includes TLS/SSL implementation)

- Delphi programmers may use a library called Indy which utilizes OpenSSL or alternatively ICS which supports TLS 1.3 now.

- GnuTLS: a free implementation (LGPL licensed)

- Java Secure Socket Extension (JSSE): the Java API and provider implementation (named SunJSSE)[183]

- LibreSSL: a fork of OpenSSL by OpenBSD project.

- MatrixSSL: a dual licensed implementation

- mbed TLS (previously PolarSSL): A tiny SSL library implementation for embedded devices that is designed for ease of use

- Network Security Services: FIPS 140 validated open source library

- OpenSSL: a free implementation (BSD license with some extensions)

- SChannel: an implementation of SSL and TLS Microsoft Windows as part of its package.

- Secure Transport: an implementation of SSL and TLS used in OS X and iOS as part of their packages.

- wolfSSL (previously CyaSSL): Embedded SSL/TLS Library with a strong focus on speed and size.

| Implementation | SSL 2.0 (insecure) | SSL 3.0 (insecure) | TLS 1.0 | TLS 1.1 | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botan | No | No[184] | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| BSAFE Micro Edition Suite | No | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | In development |

| BSAFE SSL-J | No | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| cryptlib | No | Disabled by default at compile time | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| GnuTLS | No[a] | Disabled by default[185] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[186] |

| JSSE | No[a] | Disabled by default[187] | Disabled by default[188] | Disabled by default[188] | Yes | Yes |

| LibreSSL | No[189] | No[190] | Yes | Yes | Yes | As of version 3.2.2 [191][192] |

| MatrixSSL | No | Disabled by default at compile time[193] | Yes | Yes | Yes | yes (draft version) |

| mbed TLS (previously PolarSSL) | No | Disabled by default[194] | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Network Security Services | No[b] | Disabled by default[195] | Yes | Yes[196] | Yes[197] | Yes[198] |

| OpenSSL | No[199] | Enabled by default | Yes | Yes[200] | Yes[200] | Yes[201] |

| SChannel XP / 2003[202] | Disabled by default by MSIE 7 | Enabled by default | Enabled by default by MSIE 7 | No | No | No |

| SChannel Vista[203] | Disabled by default | Enabled by default | Yes | No | No | No |

| SChannel 2008[203] | Disabled by default | Enabled by default | Yes | Disabled by default (KB4019276)[135] | Disabled by default (KB4019276)[135] | No |

| SChannel 7 / 2008 R2[204] | Disabled by default | Disabled by default in MSIE 11 | Yes | Enabled by default by MSIE 11 | Enabled by default by MSIE 11 | No |

| SChannel 8 / 2012[204] | Disabled by default | Enabled by default | Yes | Disabled by default | Disabled by default | No |

| SChannel 8.1 / 2012 R2, 10 v1507 & v1511[204] | Disabled by default | Disabled by default in MSIE 11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| SChannel 10 v1607 / 2016[145] | No | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| SChannel 10 v1903[205] | No | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| SChannel 10 v21H1[206] | No | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| SChannel 11 / 2022[207] | No | Disabled by default | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Secure Transport OS X 10.2–10.8 / iOS 1–4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Secure Transport OS X 10.9–10.10 / iOS 5–8 | No[c] | Yes | Yes | Yes[c] | Yes[c] | |

| Secure Transport OS X 10.11 / iOS 9 | No | No[c] | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Seed7 TLS/SSL Library | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| wolfSSL (previously CyaSSL) | No | Disabled by default[208] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[209] |

| Implementation | SSL 2.0 (insecure) | SSL 3.0 (insecure) | TLS 1.0 | TLS 1.1 | TLS 1.2 | TLS 1.3 |

- ^ SSL 2.0 client hello is supported for backward compatibility reasons even though SSL 2.0 is not supported.

- ^ Server-side implementation of the SSL/TLS protocol still supports processing of received v2-compatible client hello messages. [210]

- ^ Secure Transport: SSL 2.0 was discontinued in OS X 10.8. SSL 3.0 was discontinued in OS X 10.11 and iOS 9. TLS 1.1 and 1.2 are available on iOS 5.0 and later, and OS X 10.9 and later. [211]

[212]

A paper presented at the 2012 ACM conference on computer and communications security[213] showed that few applications used some of these SSL libraries correctly, leading to vulnerabilities. According to the authors

“the root cause of most of these vulnerabilities is the terrible design of the APIs to the underlying SSL libraries. Instead of expressing high-level security properties of network tunnels such as confidentiality and authentication, these APIs expose low-level details of the SSL protocol to application developers. As a consequence, developers often use SSL APIs incorrectly, misinterpreting and misunderstanding their manifold parameters, options, side effects, and return values.”

Other uses

The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) can also be protected by TLS. These applications use public key certificates to verify the identity of endpoints.