Programme d’évaluation des étudiants internationaux

Le Programme international pour le suivi des acquis des élèves ( PISA ) est une étude mondiale menée par l’ Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE) dans les pays membres et non membres visant à évaluer les systèmes éducatifs en mesurant les performances scolaires des élèves de 15 ans. sur les mathématiques, les sciences et la lecture. [1] Il a été joué pour la première fois en 2000, puis répété tous les trois ans. Son objectif est de fournir des données comparables en vue de permettre aux pays d’améliorer leurs politiques et leurs résultats en matière d’éducation. Il mesure la résolution de problèmes et la cognition. [2]

| Abréviation | PISE |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1997 |

| But | Comparaison du niveau d’instruction dans le monde |

| Quartier général | Siège de l’OCDE |

| Emplacement |

|

| Région desservie | Monde |

| Adhésion | 79 départements gouvernementaux de l’éducation |

| Langue officielle | anglais et français |

| Responsable du Pôle Petite Enfance et Ecoles | Youri Belfali |

| Orgue principal | Conseil d’administration de PISA (Présidente – Michele Bruniges) |

| Organisation mère | OCDE |

| Site Internet | ocde .org /pise |

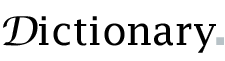

Scores moyens PISA en mathématiques (2018)

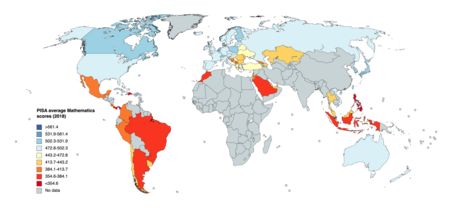

Scores moyens PISA en mathématiques (2018)  Scores moyens PISA en sciences (2018)

Scores moyens PISA en sciences (2018)  Scores moyens en lecture du PISA (2018)

Scores moyens en lecture du PISA (2018)

Les résultats de la collecte de données de 2018 ont été publiés le 3 décembre 2019. [3]

Influence et impact

Le PISA et les évaluations internationales normalisées similaires du niveau d’instruction sont de plus en plus utilisés dans le processus d’élaboration des politiques d’éducation aux niveaux national et international. [4]

Le PISA a été conçu pour replacer dans un contexte plus large les informations fournies par le suivi national des performances du système éducatif par le biais d’évaluations régulières dans un cadre commun convenu au niveau international ; en étudiant les relations entre l’apprentissage des élèves et d’autres facteurs, ils peuvent “offrir un aperçu des sources de variation des performances au sein des pays et entre les pays”. [5]

Jusqu’aux années 1990, peu de pays européens utilisaient des tests nationaux. Dans les années 1990, dix pays/régions ont introduit l’évaluation standardisée, et depuis le début des années 2000, dix autres ont emboîté le pas. En 2009, seuls cinq systèmes éducatifs européens n’avaient pas d’évaluations nationales des élèves. [4]

L’impact de ces évaluations internationales standardisées dans le domaine de la politique éducative a été significatif, en termes de création de nouvelles connaissances , de changements dans la politique d’évaluation et d’influence externe sur la politique éducative nationale plus largement.

Création de nouvelles connaissances

Les données provenant d’évaluations internationales normalisées peuvent être utiles dans la recherche sur les facteurs de causalité au sein ou entre les systèmes éducatifs. [4] Mons note que les bases de données générées par les évaluations internationales à grande échelle ont permis de réaliser des inventaires et des comparaisons des systèmes éducatifs à une échelle sans précédent* sur des thèmes allant des conditions d’apprentissage des mathématiques et de la lecture, à l’autonomie institutionnelle et aux admissions Stratégies. [6]Ils permettent de développer des typologies qui peuvent être utilisées pour des analyses statistiques comparatives des indicateurs de performance de l’éducation, identifiant ainsi les conséquences de différents choix politiques. Ils ont généré de nouvelles connaissances sur l’éducation : les résultats du PISA ont remis en question des pratiques éducatives profondément ancrées, telles que le suivi précoce des élèves vers des filières professionnelles ou universitaires. [7]

- 79 pays et économies ont participé à la collecte de données de 2018.

Barroso et de Carvalho constatent que PISA fournit une référence commune reliant la recherche universitaire en éducation et le domaine politique des politiques publiques, agissant comme un médiateur entre différents courants de connaissances du domaine de l’éducation et des politiques publiques. [8] Cependant, bien que les principales conclusions des évaluations comparatives soient largement partagées dans la communauté des chercheurs [4] , les connaissances qu’elles créent ne cadrent pas nécessairement avec les programmes de réforme du gouvernement ; cela conduit à certaines utilisations inappropriées des données d’évaluation.

Changements dans la politique nationale d’évaluation

Les recherches émergentes suggèrent que les évaluations normalisées internationales ont un impact sur les politiques et pratiques nationales d’évaluation. Le PISA est intégré dans les politiques et pratiques nationales en matière d’évaluation, de normes de programmes et d’objectifs de performance ; ses cadres et instruments d’évaluation sont utilisés comme modèles de meilleures pratiques pour améliorer les évaluations nationales ; de nombreux pays ont explicitement incorporé et mis l’accent sur les compétences de type PISA dans les normes et programmes nationaux révisés ; d’autres utilisent les données PISA pour compléter les données nationales et valider les résultats nationaux par rapport à une référence internationale. [7]

Influence externe sur la politique éducative nationale

Plus important que son influence sur la politique d’évaluation des élèves des pays, est l’éventail des façons dont PISA influence les choix de politique éducative des pays.

Les responsables politiques de la plupart des pays participants considèrent le PISA comme un indicateur important de la performance du système ; Les rapports PISA peuvent définir les problèmes politiques et fixer l’ordre du jour du débat politique national ; les décideurs politiques semblent accepter le PISA comme un instrument valable et fiable pour l’évaluation internationale des performances et des changements du système au fil du temps ; la plupart des pays, qu’ils obtiennent des résultats supérieurs, égaux ou inférieurs au score PISA moyen, ont entamé des réformes politiques en réponse aux rapports PISA. [7]

Par contre, l’impact sur les systèmes éducatifs nationaux varie considérablement. Par exemple, en Allemagne, les résultats de la première évaluation PISA ont provoqué ce que l’on appelle le « choc PISA » : une remise en question des politiques éducatives précédemment acceptées ; dans un État marqué par des divergences de politiques régionales jalousement gardées, elle a finalement abouti à un accord de tous les Länder pour introduire des normes nationales communes, voire une structure institutionnalisée pour en assurer le respect. [9] En comparaison, en Hongrie, qui partageait des conditions similaires à celles de l’Allemagne, les résultats du PISA n’ont pas entraîné de changements significatifs dans la politique éducative. [dix]

Étant donné que de nombreux pays ont fixé des objectifs de performance nationaux sur la base de leur classement relatif ou de leur score PISA absolu, les évaluations PISA ont accru l’influence de leur organe commanditaire (non élu), l’OCDE, en tant qu’observateur international de l’éducation et acteur politique, ce qui implique un important degré de « transfert de politique » du niveau international au niveau national ; PISA en particulier a « un effet normatif influent sur l’orientation des politiques nationales d’éducation ». [7]Ainsi, il est avancé que l’utilisation d’évaluations internationales normalisées a conduit à une évolution vers une responsabilisation internationale et externe pour la performance du système national ; Rey soutient que les enquêtes PISA, présentées comme des diagnostics objectifs et indépendants des systèmes éducatifs, servent en fait à promouvoir des orientations spécifiques sur les questions éducatives. [4]

Les acteurs politiques nationaux se réfèrent aux pays PISA très performants pour “aider à légitimer et justifier leur programme de réforme prévu dans le cadre de débats politiques nationaux contestés”. [11] Les données PISA peuvent être “utilisées pour alimenter des débats de longue date autour de conflits ou de rivalités préexistants entre différentes options politiques, comme dans la Communauté française de Belgique”. [12] Dans de tels cas, les données d’évaluation PISA sont utilisées de manière sélective : dans le discours public, les gouvernements n’utilisent souvent que des caractéristiques superficielles des enquêtes PISA telles que les classements des pays et non les analyses plus détaillées. Rey (2010 : 145, citant Greger, 2008) note que les résultats réels des évaluations PISA sont souvent ignorés, car les décideurs se réfèrent de manière sélective aux données afin de légitimer des politiques introduites pour d’autres raisons. [13]

De plus, les comparaisons internationales de PISA peuvent être utilisées pour justifier des réformes avec lesquelles les données elles-mêmes n’ont aucun lien ; au Portugal, par exemple, les données PISA ont été utilisées pour justifier de nouvelles modalités d’évaluation des enseignants (basées sur des déductions qui n’étaient pas justifiées par les évaluations et les données elles-mêmes) ; ils ont également alimenté le discours du gouvernement sur la question des redoublements (ce qui, selon les recherches, n’améliore pas les résultats des élèves). [14] En Finlande, les résultats PISA du pays (qui sont jugés excellents dans d’autres pays) ont été utilisés par les ministres pour promouvoir de nouvelles politiques en faveur des élèves « doués ». [15]De telles utilisations et interprétations supposent souvent des relations causales qui ne peuvent légitimement être fondées sur des données PISA qui nécessiteraient normalement une enquête plus approfondie par le biais d’études qualitatives approfondies et d’enquêtes longitudinales basées sur des méthodes mixtes quantitatives et qualitatives [16] , que les politiques sont souvent réticents à financer.

Les dernières décennies ont vu une expansion des utilisations du PISA et des évaluations similaires, allant de l’évaluation de l’apprentissage des élèves à la connexion « du domaine éducatif (leur mandat traditionnel) au domaine politique ». [17] Cela soulève la question de savoir si les données PISA sont suffisamment robustes pour supporter le poids des décisions politiques majeures qui sont fondées sur elles, car, selon Breakspear, les données PISA « en sont venues à façonner, définir et évaluer de plus en plus les principaux objectifs du système éducatif national / fédéral ». [7] Cela implique que ceux qui fixent les tests PISA – par exemple en choisissant le contenu à évaluer et non évalué – sont dans une position de pouvoir considérable pour fixer les termes du débat sur l’éducation,[7]

Cadre

PISA s’inscrit dans une tradition d’études scolaires internationales, entreprises depuis la fin des années 1950 par l’ Association internationale pour l’évaluation du rendement scolaire (IEA). Une grande partie de la méthodologie du PISA suit l’exemple de l’ étude TIMSS ( Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study ), lancée en 1995, qui à son tour a été fortement influencée par l’ évaluation nationale américaine des progrès de l’éducation (NAEP). La composante lecture du PISA s’inspire de l’ étude internationale Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) de l’IEA.

PISA vise à tester la compétence des élèves en littératie dans trois domaines : lecture, mathématiques, sciences sur une échelle indéfinie. [18]

Le test PISA de littératie en mathématiques demande aux élèves d’appliquer leurs connaissances en mathématiques pour résoudre des problèmes posés dans des contextes réels. Pour résoudre les problèmes, les élèves doivent activer un certain nombre de compétences mathématiques ainsi qu’un large éventail de connaissances en contenu mathématique. TIMSS, d’autre part, mesure le contenu plus traditionnel de la classe, comme la compréhension des fractions et des nombres décimaux et la relation entre eux (réussite du programme). PISA prétend mesurer l’application de l’éducation aux problèmes de la vie réelle et à l’apprentissage tout au long de la vie (connaissance de la main-d’œuvre).

Dans le test de lecture, “OCDE/PISA ne mesure pas dans quelle mesure les élèves de 15 ans lisent couramment ou dans quelle mesure ils sont compétents pour les tâches de reconnaissance de mots ou d’orthographe”. Au lieu de cela, ils devraient être capables de “construire, étendre et réfléchir sur le sens de ce qu’ils ont lu à travers un large éventail de textes continus et non continus”. [19]

PISA évalue également les étudiants dans des domaines innovants. En 2012 et 2015, en plus de la lecture, des mathématiques et des sciences, ils ont été testés en résolution collaborative de problèmes. En 2018, le domaine innovant supplémentaire était la compétence globale.

Mise en œuvre

Le PISA est parrainé, régi et coordonné par l’OCDE, mais financé par les pays participants. [ citation nécessaire ]

Méthode de test

Échantillonnage

Les élèves testés par PISA sont âgés entre 15 ans et 3 mois et 16 ans et 2 mois au début de la période d’évaluation. L’année scolaire dans laquelle se trouvent les élèves n’est pas prise en compte. Seuls les élèves de l’école sont testés, pas les élèves à domicile. Dans le PISA 2006, cependant, plusieurs pays ont également utilisé un échantillon d’élèves basé sur l’année scolaire. Cela a permis d’étudier comment l’âge et l’année scolaire interagissent.

Pour répondre aux exigences de l’OCDE, chaque pays doit constituer un échantillon d’au moins 5 000 étudiants. Dans de petits pays comme l’Islande et le Luxembourg , où il y a moins de 5 000 étudiants par an, c’est toute une cohorte d’âge qui est testée. Certains pays ont utilisé des échantillons beaucoup plus grands que nécessaire pour permettre des comparaisons entre les régions.

Test

Documents de test PISA sur une table d’école (Neues Gymnasium, Oldenburg, Allemagne, 2006)

Documents de test PISA sur une table d’école (Neues Gymnasium, Oldenburg, Allemagne, 2006)

Chaque étudiant passe un test sur ordinateur de deux heures. Une partie du test est à choix multiples et une partie implique des réponses plus complètes. Il y a six heures et demie de matériel d’évaluation, mais chaque étudiant n’est pas testé sur toutes les parties. Après le test cognitif, les élèves participants passent près d’une heure de plus à répondre à un questionnaire sur leurs antécédents, y compris les habitudes d’apprentissage, la motivation et la famille. Les directeurs d’école remplissent un questionnaire décrivant la démographie de l’école, le financement, etc. En 2012, les participants se sont vu proposer, pour la première fois dans l’histoire des tests et des évaluations à grande échelle, un nouveau type de problème, à savoir des problèmes interactifs (complexes) nécessitant une exploration. d’un nouvel appareil virtuel. [20] [21]

Dans certains pays, PISA a commencé à expérimenter des tests adaptatifs sur ordinateur .

Suppléments nationaux

Les pays sont autorisés à combiner PISA avec des tests nationaux complémentaires.

L’Allemagne le fait de manière très extensive : le lendemain du test international, les élèves passent un test national appelé PISA-E (E=Ergänzung=complément). Les items du test PISA-E sont plus proches de TIMSS que de PISA. Alors qu’environ 5 000 étudiants allemands seulement participent aux tests internationaux et nationaux, 45 000 autres ne passent que le test national. Ce grand échantillon est nécessaire pour permettre une analyse par États fédéraux. Suite à un désaccord sur l’interprétation des résultats de 2006, l’OCDE a averti l’Allemagne qu’elle pourrait retirer le droit d’utiliser le label “PISA” pour les tests nationaux. [22]

Mise à l’échelle des données

Dès le début, PISA a été conçu avec une méthode particulière d’analyse des données à l’esprit. Étant donné que les élèves travaillent sur différents cahiers de test, les scores bruts doivent être « mis à l’échelle » pour permettre des comparaisons significatives. Les scores sont donc échelonnés de sorte que la moyenne de l’OCDE dans chaque domaine (mathématiques, lecture et sciences) soit de 500 et l’ écart type de 100. [23] Cela n’est vrai que pour le cycle PISA initial lorsque l’échelle a été introduite pour la première fois, les cycles sont liés aux cycles précédents par des méthodes de liaison d’échelle IRT. [24]

Cette génération d’estimations de compétence est effectuée à l’aide d’une extension de régression latente du modèle de Rasch , un modèle de théorie de la réponse aux items (IRT), également appelé modèle de conditionnement ou modèle de population. Les estimations de compétence sont fournies sous la forme de valeurs dites plausibles, qui permettent des estimations non biaisées des différences entre les groupes. La régression latente, associée à l’utilisation d’une distribution de probabilité a priori gaussienne des compétences des élèves, permet d’estimer les distributions des compétences des groupes d’élèves participants. [25] Les procédures de mise à l’échelle et de conditionnement sont décrites en termes presque identiques dans les rapports techniques de PISA 2000, 2003, 2006. NAEP et TIMSS utilisent des méthodes de mise à l’échelle similaires.

Résultats du classement

Tous les résultats du PISA sont compilés par pays ; les cycles PISA récents ont des résultats provinciaux ou régionaux distincts pour certains pays. La plupart de l’attention du public se concentre sur un seul résultat : les scores moyens des pays et leur classement des pays les uns par rapport aux autres. Dans les rapports officiels, cependant, les classements pays par pays ne sont pas présentés sous forme de simples tableaux de classement, mais sous forme de tableaux croisés indiquant pour chaque paire de pays si les différences de scores moyens sont ou non statistiquement significatives (peu susceptibles d’être dues à des fluctuations aléatoires dans l’échantillonnage des élèves ou dans le fonctionnement de l’élément). Dans les cas favorables, une différence de 9 points est suffisante pour être considérée comme significative. [ citation nécessaire ]

Le PISA ne combine jamais les scores des domaines des mathématiques, des sciences et de la lecture dans un score global. Cependant, les commentateurs ont parfois combiné les résultats des tests des trois domaines dans un classement général des pays. Une telle méta-analyse n’est pas approuvée par l’OCDE, bien que les résumés officiels utilisent parfois les scores du domaine principal d’un cycle de test comme indicateur des capacités globales des élèves.

Résumé du classement PISA 2018

Les résultats du PISA 2018 ont été présentés le 3 décembre 2019, qui comprenaient des données pour environ 600 000 étudiants participants dans 79 pays et économies, la zone économique chinoise de Pékin , Shanghai , Jiangsu et Zhejiang émergeant comme la plus performante dans toutes les catégories. Notez que cela ne représente pas l’intégralité de la Chine continentale. [26] Les résultats de lecture pour l’Espagne n’ont pas été publiés en raison d’anomalies perçues. [27]

| Mathématiques | Science | Lecture | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Comparaison des classements 2003–2015

| Mathématiques | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pays | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | |||||||

| Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | |||

| Moyenne internationale (OCDE) | 490 | — | 494 | — | 495 | — | 494 | — | 499 | — | ||

| |

413 | 57 | 394 | 54 | 377 | 53 | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

360 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

409 | 58 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

494 | 25 | 504 | 17 | 514 | 13 | 520 | 12 | 524 | dix | ||

| |

497 | 20 | 506 | 16 | 496 | 22 | 505 | 17 | 506 | 18 | ||

| |

531 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

507 | 15 | 515 | 13 | 515 | 12 | 520 | 11 | 529 | 7 | ||

| |

377 | 68 | 389 | 55 | 386 | 51 | 370 | 50 | 356 | 39 | ||

| |

441 | 47 | 439 | 43 | 428 | 41 | 413 | 43 | — | — | ||

| |

456 | 43 | 418 | 49 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

516 | dix | 518 | 11 | 527 | 8 | 527 | 7 | 532 | 6 | ||

| |

423 | 50 | 423 | 47 | 421 | 44 | 411 | 44 | — | — | ||

| |

542 | 4 | 560 | 3 | 543 | 4 | 549 | 1 | — | — | ||

| |

390 | 64 | 376 | 58 | 381 | 52 | 370 | 49 | — | — | ||

| |

400 | 62 | 407 | 53 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

464 | 41 | 471 | 38 | 460 | 38 | 467 | 34 | — | — | ||

| |

437 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

492 | 28 | 499 | 22 | 493 | 25 | 510 | 15 | 516 | 12 | ||

| |

511 | 12 | 500 | 20 | 503 | 17 | 513 | 14 | 514 | 14 | ||

| |

328 | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

520 | 9 | 521 | 9 | 512 | 15 | 515 | 13 | — | — | ||

| |

511 | 13 | 519 | dix | 541 | 5 | 548 | 2 | 544 | 2 | ||

| |

493 | 26 | 495 | 23 | 497 | 20 | 496 | 22 | 511 | 15 | ||

| |

371 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

404 | 60 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

506 | 16 | 514 | 14 | 513 | 14 | 504 | 19 | 503 | 19 | ||

| |

454 | 44 | 453 | 40 | 466 | 37 | 459 | 37 | 445 | 32 | ||

| |

548 | 2 | 561 | 2 | 555 | 2 | 547 | 3 | 550 | 1 | ||

| |

477 | 37 | 477 | 37 | 490 | 27 | 491 | 26 | 490 | 25 | ||

| |

488 | 31 | 493 | 25 | 507 | 16 | 506 | 16 | 515 | 13 | ||

| |

386 | 66 | 375 | 60 | 371 | 55 | 391 | 47 | 360 | 37 | ||

| |

504 | 18 | 501 | 18 | 487 | 30 | 501 | 21 | 503 | 20 | ||

| |

470 | 39 | 466 | 39 | 447 | 39 | 442 | 38 | — | — | ||

| |

490 | 30 | 485 | 30 | 483 | 33 | 462 | 36 | 466 | 31 | ||

| |

532 | 5 | 536 | 6 | 529 | 7 | 523 | 9 | 534 | 5 | ||

| |

380 | 67 | 386 | 57 | 387 | 50 | 384 | 48 | — | — | ||

| |

460 | 42 | 432 | 45 | 405 | 48 | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

524 | 7 | 554 | 4 | 546 | 3 | 547 | 4 | 542 | 3 | ||

| |

362 | 71 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

482 | 34 | 491 | 26 | 482 | 34 | 486 | 30 | 483 | 27 | ||

| |

396 | 63 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

478 | 36 | 479 | 35 | 477 | 35 | 486 | 29 | — | — | ||

| |

486 | 33 | 490 | 27 | 489 | 28 | 490 | 27 | 493 | 23 | ||

| |

544 | 3 | 538 | 5 | 525 | dix | 525 | 8 | 527 | 8 | ||

| |

446 | 45 | 421 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

479 | 35 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

408 | 59 | 413 | 50 | 419 | 46 | 406 | 45 | 385 | 36 | ||

| |

420 | 52 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

418 | 54 | 410 | 51 | 403 | 49 | 399 | 46 | — | — | ||

| |

512 | 11 | 523 | 8 | 526 | 9 | 531 | 5 | 538 | 4 | ||

| |

495 | 21 | 500 | 21 | 519 | 11 | 522 | dix | 523 | 11 | ||

| |

502 | 19 | 489 | 28 | 498 | 19 | 490 | 28 | 495 | 22 | ||

| |

387 | 65 | 368 | 61 | 365 | 57 | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

504 | 17 | 518 | 12 | 495 | 23 | 495 | 24 | 490 | 24 | ||

| |

492 | 29 | 487 | 29 | 487 | 31 | 466 | 35 | 466 | 30 | ||

| |

402 | 61 | 376 | 59 | 368 | 56 | 318 | 52 | — | — | ||

| |

444 | 46 | 445 | 42 | 427 | 42 | 415 | 42 | — | — | ||

| |

494 | 23 | 482 | 32 | 468 | 36 | 476 | 32 | 468 | 29 | ||

| |

564 | 1 | 573 | 1 | 562 | 1 | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

475 | 38 | 482 | 33 | 497 | 21 | 492 | 25 | 498 | 21 | ||

| |

510 | 14 | 501 | 19 | 501 | 18 | 504 | 18 | — | — | ||

| |

486 | 32 | 484 | 31 | 483 | 32 | 480 | 31 | 485 | 26 | ||

| |

494 | 24 | 478 | 36 | 494 | 24 | 502 | 20 | 509 | 16 | ||

| |

521 | 8 | 531 | 7 | 534 | 6 | 530 | 6 | 527 | 9 | ||

| |

415 | 56 | 427 | 46 | 419 | 45 | 417 | 41 | 417 | 35 | ||

| |

417 | 55 | — | — | 414 | 47 | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

367 | 70 | 388 | 56 | 371 | 54 | 365 | 51 | 359 | 38 | ||

| |

420 | 51 | 448 | 41 | 445 | 40 | 424 | 40 | 423 | 33 | ||

| |

427 | 49 | 434 | 44 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| |

492 | 27 | 494 | 24 | 492 | 26 | 495 | 23 | 508 | 17 | ||

| |

470 | 40 | 481 | 34 | 487 | 29 | 474 | 33 | 483 | 28 | ||

| |

418 | 53 | 409 | 52 | 427 | 43 | 427 | 39 | 422 | 34 | ||

| |

495 | 22 | 511 | 15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Science | ||||||||||||

| Pays | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | ||||||||

| Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | |||||

| Moyenne internationale (OCDE) | 493 | — | 501 | — | 501 | — | 498 | — | ||||

| |

427 | 54 | 397 | 58 | 391 | 54 | — | — | ||||

| |

376 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

432 | 52 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

510 | 14 | 521 | 14 | 527 | 9 | 527 | 8 | ||||

| |

495 | 26 | 506 | 21 | 494 | 28 | 511 | 17 | ||||

| |

518 | dix | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

502 | 20 | 505 | 22 | 507 | 19 | 510 | 18 | ||||

| |

401 | 66 | 402 | 55 | 405 | 49 | 390 | 49 | ||||

| |

446 | 46 | 446 | 43 | 439 | 42 | 434 | 40 | ||||

| |

475 | 38 | 425 | 49 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

528 | 7 | 525 | 9 | 529 | 7 | 534 | 3 | ||||

| |

447 | 45 | 445 | 44 | 447 | 41 | 438 | 39 | ||||

| |

532 | 4 | 523 | 11 | 520 | 11 | 532 | 4 | ||||

| |

416 | 60 | 399 | 56 | 402 | 50 | 388 | 50 | ||||

| |

420 | 58 | 429 | 47 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

475 | 37 | 491 | 32 | 486 | 35 | 493 | 25 | ||||

| |

433 | 51 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

493 | 29 | 508 | 20 | 500 | 22 | 513 | 14 | ||||

| |

502 | 21 | 498 | 25 | 499 | 24 | 496 | 23 | ||||

| |

332 | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

534 | 3 | 541 | 5 | 528 | 8 | 531 | 5 | ||||

| |

531 | 5 | 545 | 4 | 554 | 1 | 563 | 1 | ||||

| |

495 | 27 | 499 | 24 | 498 | 25 | 495 | 24 | ||||

| |

384 | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

411 | 63 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

509 | 16 | 524 | dix | 520 | 12 | 516 | 12 | ||||

| |

455 | 44 | 467 | 40 | 470 | 38 | 473 | 37 | ||||

| |

523 | 9 | 555 | 1 | 549 | 2 | 542 | 2 | ||||

| |

477 | 35 | 494 | 30 | 503 | 20 | 504 | 20 | ||||

| |

473 | 39 | 478 | 37 | 496 | 26 | 491 | 26 | ||||

| |

403 | 65 | 382 | 60 | 383 | 55 | 393 | 48 | ||||

| |

503 | 19 | 522 | 13 | 508 | 18 | 508 | 19 | ||||

| |

467 | 40 | 470 | 39 | 455 | 39 | 454 | 38 | ||||

| |

481 | 34 | 494 | 31 | 489 | 33 | 475 | 35 | ||||

| |

538 | 2 | 547 | 3 | 539 | 4 | 531 | 6 | ||||

| |

409 | 64 | 409 | 54 | 415 | 47 | 422 | 43 | ||||

| |

456 | 43 | 425 | 48 | 400 | 53 | — | — | ||||

| |

516 | 11 | 538 | 6 | 538 | 5 | 522 | dix | ||||

| |

378 | 71 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

490 | 31 | 502 | 23 | 494 | 29 | 490 | 27 | ||||

| |

386 | 68 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

475 | 36 | 496 | 28 | 491 | 31 | 488 | 31 | ||||

| |

483 | 33 | 491 | 33 | 484 | 36 | 486 | 33 | ||||

| |

529 | 6 | 521 | 15 | 511 | 16 | 511 | 16 | ||||

| |

443 | 47 | 420 | 50 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

465 | 41 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

416 | 61 | 415 | 52 | 416 | 46 | 410 | 47 | ||||

| |

428 | 53 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

411 | 62 | 410 | 53 | 401 | 51 | 412 | 46 | ||||

| |

509 | 17 | 522 | 12 | 522 | dix | 525 | 9 | ||||

| |

513 | 12 | 516 | 16 | 532 | 6 | 530 | 7 | ||||

| |

498 | 24 | 495 | 29 | 500 | 23 | 487 | 32 | ||||

| |

397 | 67 | 373 | 61 | 369 | 57 | — | — | ||||

| |

501 | 22 | 526 | 8 | 508 | 17 | 498 | 22 | ||||

| |

501 | 23 | 489 | 34 | 493 | 30 | 474 | 36 | ||||

| |

418 | 59 | 384 | 59 | 379 | 56 | 349 | 52 | ||||

| |

435 | 50 | 439 | 46 | 428 | 43 | 418 | 45 | ||||

| |

487 | 32 | 486 | 35 | 478 | 37 | 479 | 34 | ||||

| |

556 | 1 | 551 | 2 | 542 | 3 | — | — | ||||

| |

461 | 42 | 471 | 38 | 490 | 32 | 488 | 29 | ||||

| |

513 | 13 | 514 | 18 | 512 | 15 | 519 | 11 | ||||

| |

493 | 30 | 496 | 27 | 488 | 34 | 488 | 30 | ||||

| |

493 | 28 | 485 | 36 | 495 | 27 | 503 | 21 | ||||

| |

506 | 18 | 515 | 17 | 517 | 13 | 512 | 15 | ||||

| |

421 | 57 | 444 | 45 | 425 | 45 | 421 | 44 | ||||

| |

425 | 56 | — | — | 410 | 48 | — | — | ||||

| |

386 | 69 | 398 | 57 | 401 | 52 | 386 | 51 | ||||

| |

425 | 55 | 463 | 41 | 454 | 40 | 424 | 42 | ||||

| |

437 | 48 | 448 | 42 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| |

509 | 15 | 514 | 19 | 514 | 14 | 515 | 13 | ||||

| |

496 | 25 | 497 | 26 | 502 | 21 | 489 | 28 | ||||

| |

435 | 49 | 416 | 51 | 427 | 44 | 428 | 41 | ||||

| |

525 | 8 | 528 | 7 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Lecture | ||||||||||||

| Pays | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | 2000 | ||||||

| Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | Score | Rang | |

| Moyenne internationale (OCDE) | 493 | — | 496 | — | 493 | — | 489 | — | 494 | — | 493 | — |

| |

405 | 63 | 394 | 58 | 385 | 55 | — | — | — | — | 349 | 39 |

| |

350 | 71 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

425 | 56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

503 | 16 | 512 | 12 | 515 | 8 | 513 | 7 | 525 | 4 | 528 | 4 |

| |

485 | 33 | 490 | 26 | 470 | 37 | 490 | 21 | 491 | 22 | 492 | 19 |

| |

494 | 27 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

499 | 20 | 509 | 16 | 506 | 10 | 501 | 11 | 507 | 11 | 507 | 11 |

| |

407 | 62 | 407 | 52 | 412 | 49 | 393 | 47 | 403 | 36 | 396 | 36 |

| |

432 | 49 | 436 | 47 | 429 | 42 | 402 | 43 | — | — | 430 | 32 |

| |

475 | 38 | 429 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

527 | 3 | 523 | 7 | 524 | 5 | 527 | 4 | 528 | 3 | 534 | 2 |

| |

459 | 42 | 441 | 43 | 449 | 41 | 442 | 37 | — | — | 410 | 35 |

| |

497 | 23 | 523 | 8 | 495 | 21 | 496 | 15 | — | — | — | — |

| |

425 | 57 | 403 | 54 | 413 | 48 | 385 | 49 | — | — | — | — |

| |

427 | 52 | 441 | 45 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

487 | 31 | 485 | 33 | 476 | 34 | 477 | 29 | — | — | — | — |

| |

443 | 45 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

487 | 30 | 493 | 24 | 478 | 32 | 483 | 25 | 489 | 24 | 492 | 20 |

| |

500 | 18 | 496 | 23 | 495 | 22 | 494 | 18 | 492 | 19 | 497 | 16 |

| |

358 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

519 | 6 | 516 | 10 | 501 | 12 | 501 | 12 | — | — | — | — |

| |

526 | 4 | 524 | 5 | 536 | 2 | 547 | 2 | 543 | 1 | 546 | 1 |

| |

499 | 19 | 505 | 19 | 496 | 20 | 488 | 22 | 496 | 17 | 505 | 14 |

| |

352 | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 373 | 37 |

| |

401 | 65 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

509 | 11 | 508 | 18 | 497 | 18 | 495 | 17 | 491 | 21 | 484 | 22 |

| |

467 | 41 | 477 | 38 | 483 | 30 | 460 | 35 | 472 | 30 | 474 | 25 |

| |

527 | 2 | 545 | 1 | 533 | 3 | 536 | 3 | 510 | 9 | 525 | 6 |

| |

470 | 40 | 488 | 28 | 494 | 24 | 482 | 26 | 482 | 25 | 480 | 23 |

| |

482 | 35 | 483 | 35 | 500 | 15 | 484 | 23 | 492 | 20 | 507 | 12 |

| |

397 | 67 | 396 | 57 | 402 | 53 | 393 | 46 | 382 | 38 | 371 | 38 |

| |

521 | 5 | 523 | 6 | 496 | 19 | 517 | 6 | 515 | 6 | 527 | 5 |

| |

479 | 37 | 486 | 32 | 474 | 35 | 439 | 39 | — | — | 452 | 29 |

| |

485 | 34 | 490 | 25 | 486 | 27 | 469 | 32 | 476 | 29 | 487 | 21 |

| |

516 | 8 | 538 | 3 | 520 | 7 | 498 | 14 | 498 | 14 | 522 | 9 |

| |

408 | 61 | 399 | 55 | 405 | 51 | 401 | 44 | — | — | — | — |

| |

427 | 54 | 393 | 59 | 390 | 54 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

517 | 7 | 536 | 4 | 539 | 1 | 556 | 1 | 534 | 2 | 525 | 7 |

| |

347 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

488 | 29 | 489 | 27 | 484 | 28 | 479 | 27 | 491 | 23 | 458 | 28 |

| |

347 | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

472 | 39 | 477 | 37 | 468 | 38 | 470 | 31 | — | — | — | — |

| |

481 | 36 | 488 | 30 | 472 | 36 | 479 | 28 | 479 | 27 | 441 | 30 |

| |

509 | 12 | 509 | 15 | 487 | 26 | 492 | 20 | 498 | 15 | — | — |

| |

431 | 50 | 398 | 56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

447 | 44 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

423 | 58 | 424 | 49 | 425 | 44 | 410 | 42 | 400 | 37 | 422 | 34 |

| |

416 | 59 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

427 | 55 | 422 | 50 | 408 | 50 | 392 | 48 | — | — | — | — |

| |

503 | 15 | 511 | 13 | 508 | 9 | 507 | 10 | 513 | 8 | ‡ | ‡ |

| |

509 | 10 | 512 | 11 | 521 | 6 | 521 | 5 | 522 | 5 | 529 | 3 |

| |

513 | 9 | 504 | 20 | 503 | 11 | 484 | 24 | 500 | 12 | 505 | 13 |

| |

398 | 66 | 384 | 61 | 370 | 57 | — | — | — | — | 327 | 40 |

| |

506 | 13 | 518 | 9 | 500 | 14 | 508 | 8 | 497 | 16 | 479 | 24 |

| |

498 | 21 | 488 | 31 | 489 | 25 | 472 | 30 | 478 | 28 | 470 | 26 |

| |

402 | 64 | 388 | 60 | 372 | 56 | 312 | 51 | — | — | — | — |

| |

434 | 47 | 438 | 46 | 424 | 45 | 396 | 45 | — | — | 428 | 33 |

| |

495 | 26 | 475 | 40 | 459 | 40 | 440 | 38 | 442 | 32 | 462 | 27 |

| |

535 | 1 | 542 | 2 | 526 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

453 | 43 | 463 | 41 | 477 | 33 | 466 | 33 | 469 | 31 | — | — |

| |

505 | 14 | 481 | 36 | 483 | 29 | 494 | 19 | — | — | — | — |

| |

496 | 25 | 488 | 29 | 481 | 31 | 461 | 34 | 481 | 26 | 493 | 18 |

| |

500 | 17 | 483 | 34 | 497 | 17 | 507 | 9 | 514 | 7 | 516 | 10 |

| |

492 | 28 | 509 | 14 | 501 | 13 | 499 | 13 | 499 | 13 | 494 | 17 |

| |

409 | 60 | 441 | 44 | 421 | 46 | 417 | 40 | 420 | 35 | 431 | 31 |

| |

427 | 53 | — | — | 416 | 47 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

361 | 68 | 404 | 53 | 404 | 52 | 380 | 50 | 375 | 39 | — | — |

| |

428 | 51 | 475 | 39 | 464 | 39 | 447 | 36 | 441 | 33 | — | — |

| |

434 | 48 | 442 | 42 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| |

498 | 22 | 499 | 21 | 494 | 23 | 495 | 16 | 507 | 10 | 523 | 8 |

| |

497 | 24 | 498 | 22 | 500 | 16 | — | — | 495 | 18 | 504 | 15 |

| |

437 | 46 | 411 | 51 | 426 | 43 | 413 | 41 | 434 | 34 | — | — |

| |

487 | 32 | 508 | 17 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

- ^ a b c Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang

- ^ a b c Shanghai (2009, 2012); Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Guangdong (2015)

- ^ a b c Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires

Previous years

| Period | Focus | OECD countries | Partner countries | Participating students | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Reading | 28 | 4 + 11 | 265,000 | The Netherlands disqualified from data analysis. 11 additional non-OECD countries took the test in 2002. |

| 2003 | Mathematics | 30 | 11 | 275,000 | UK disqualified from data analysis. Also included test in problem solving. |

| 2006 | Science | 30 | 27 | 400,000 | Reading scores for US disqualified from analysis due to misprint in testing materials.[28] |

| 2009[29] | Reading | 34 | 41 + 10 | 470,000 | 10 additional non-OECD countries took the test in 2010.[30][31] |

| 2012[32] | Mathematics | 34 | 31 | 510,000 |

Reception

(China) China’s participation in the 2012 test was limited to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Macau as separate entities. In 2012, Shanghai participated for the second time, again topping the rankings in all three subjects, as well as improving scores in the subjects compared to the 2009 tests. Shanghai’s score of 613 in mathematics was 113 points above the average score, putting the performance of Shanghai pupils about 3 school years ahead of pupils in average countries. Educational experts debated to what degree this result reflected the quality of the general educational system in China, pointing out that Shanghai has greater wealth and better-paid teachers than the rest of China.[33] Hong Kong placed second in reading and science and third in maths.

Andreas Schleicher, PISA division head and co-ordinator, stated that PISA tests administered in rural China have produced some results approaching the OECD average. Citing further as-yet-unpublished OECD research, he said, “We have actually done PISA in 12 of the provinces in China. Even in some of the very poor areas you get performance close to the OECD average.”[34] Schleicher believes that China has also expanded school access and has moved away from learning by rote,[35] performing well in both rote-based and broader assessments.[34]

In 2018 the Chinese provinces that participated were Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang. In 2015, the participating provinces were Jiangsu, Guangdong, Beijing, and Shanghai.[36] The 2015 Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Guangdong cohort scored a median 518 in science in 2015, while the 2012 Shanghai cohort scored a median 580.

Critics of PISA counter that in Shanghai and other Chinese cities, most children of migrant workers can only attend city schools up to the ninth grade, and must return to their parents’ hometowns for high school due to hukou restrictions, thus skewing the composition of the city’s high school students in favor of wealthier local families. A population chart of Shanghai reproduced in The New York Times shows a steep drop off in the number of 15-year-olds residing there.[37] According to Schleicher, 27% of Shanghai’s 15-year-olds are excluded from its school system (and hence from testing). As a result, the percentage of Shanghai’s 15-year-olds tested by PISA was 73%, lower than the 89% tested in the US.[38] Following the 2015 testing, OECD published in depth studies on the education systems of a selected few countries including China.[39]

In 2014, Liz Truss, the British Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department for Education, led a fact-finding visit to schools and teacher-training centres in Shanghai.[40] Britain increased exchanges with Chinese teachers and schools to find out how to improve quality. In 2014, 60 teachers from Shanghai were invited to the UK to help share their teaching methods, support pupils who are struggling, and help to train other teachers.[41] In 2016, Britain invited 120 Chinese teachers, planning to adopt Chinese styles of teaching in 8,000 aided schools.[42] By 2019, approximately 5,000 of Britain’s 16,000 primary schools had adopted the Shanghai’s teaching methods.[43] The performance of British schools in PISA improved after adopting China’s teaching styles.[44][45]

Finland

Finland, which received several top positions in the first tests, fell in all three subjects in 2012, but remained the best performing country overall in Europe, achieving their best result in science with 545 points (5th) and worst in mathematics with 519 (12th) in which the country was outperformed by four other European countries. The drop in mathematics was 25 points since 2003, the last time mathematics was the focus of the tests. For the first time Finnish girls outperformed boys in mathematics narrowly. It was also the first time pupils in Finnish-speaking schools did not perform better than pupils in Swedish-speaking schools. Minister of Education and Science Krista Kiuru expressed concern for the overall drop, as well as the fact that the number of low-performers had increased from 7% to 12%.[46]

India

India participated in the 2009 round of testing but pulled out of the 2012 PISA testing, with the Indian government attributing its action to the unfairness of PISA testing to Indian students.[47] The Indian Express reported, “The ministry (of education) has concluded that there was a socio-cultural disconnect between the questions and Indian students. The ministry will write to the OECD and drive home the need to factor in India’s “socio-cultural milieu”. India’s participation in the next PISA cycle will hinge on this”.[48] The Indian Express also noted that “Considering that over 70 nations participate in PISA, it is uncertain whether an exception would be made for India”.

India did not participate in the 2012, 2015 and 2018 PISA rounds.[49]

A Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan (KVS) committee as well as a group of secretaries on education constituted by the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi recommended that India should participate in PISA. Accordingly, in February 2017, the Ministry of Human Resource Development under Prakash Javadekar decided to end the boycott and participate in PISA from 2020. To address the socio-cultural disconnect between the test questions and students, it was reported that the OECD will update some questions. For example, the word avocado in a question may be replaced with a more popular Indian fruit such as mango.[50]

Malaysia

In 2015, the results from Malaysia were found by the OECD to have not met the maximum response rate.[51] Opposition politician Ong Kian Ming said the education ministry tried to oversample high-performing students in rich schools.[52][53]

Sweden

Sweden’s result dropped in all three subjects in the 2012 test, which was a continuation of a trend from 2006 and 2009. It saw the sharpest fall in mathematics performance with a drop in score from 509 in 2003 to 478 in 2012. The score in reading showed a drop from 516 in 2000 to 483 in 2012. The country performed below the OECD average in all three subjects.[54] The leader of the opposition, Social Democrat Stefan Löfven, described the situation as a national crisis.[55] Along with the party’s spokesperson on education, Ibrahim Baylan, he pointed to the downward trend in reading as most severe.[55]

In 2020, Swedish newspaper Expressen revealed that Sweden had inflated their score in PISA 2018 by not conforming to OECD standards. According to professor Magnus Henrekson a large number of foreign-born students had not been tested.[56]

United Kingdom

In the 2012 test, as in 2009, the result was slightly above average for the United Kingdom, with the science ranking being highest (20).[57] England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland also participated as separated entities, showing the worst result for Wales which in mathematics was 43rd of the 65 countries and economies. Minister of Education in Wales Huw Lewis expressed disappointment in the results, said that there were no “quick fixes”, but hoped that several educational reforms that have been implemented in the last few years would give better results in the next round of tests.[58] The United Kingdom had a greater gap between high- and low-scoring students than the average. There was little difference between public and private schools when adjusted for Socio-economic background of students. The gender difference in favour of girls was less than in most other countries, as was the difference between natives and immigrants.[57]

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard warned against putting too much emphasis on the UK’s international ranking, arguing that an overfocus on scholarly performances in East Asia might have contributed to the area’s low Birthrate, which he argued could harm the economic performance in the future more than a good PISA score would outweigh.[59]

In 2013, the Times Educational Supplement (TES) published an article, “Is PISA Fundamentally Flawed?” by William Stewart, detailing serious critiques of PISA‘s conceptual foundations and methods advanced by statisticians at major universities.[60]

In the article, Professor Harvey Goldstein of the University of Bristol was quoted as saying that when the OECD tries to rule out questions suspected of bias, it can have the effect of “smoothing out” key differences between countries. “That is leaving out many of the important things,” he warned. “They simply don’t get commented on. What you are looking at is something that happens to be common. But (is it) worth looking at? PISA results are taken at face value as providing some sort of common standard across countries. But as soon as you begin to unpick it, I think that all falls apart.”

Queen’s University Belfast mathematician Dr. Hugh Morrison stated that he found the statistical model underlying PISA to contain a fundamental, insoluble mathematical error that renders PISA rankings “valueless”.[61] Goldstein remarked that Dr. Morrison’s objection highlights “an important technical issue” if not a “profound conceptual error”. However, Goldstein cautioned that PISA has been “used inappropriately”, contending that some of the blame for this “lies with PISA itself. I think it tends to say too much for what it can do and it tends not to publicise the negative or the weaker aspects.” Professors Morrison and Goldstein expressed dismay at the OECD’s response to criticism. Morrison said that when he first published his criticisms of PISA in 2004 and also personally queried several of the OECD’s “senior people” about them, his points were met with “absolute silence” and have yet to be addressed. “I was amazed at how unforthcoming they were,” he told TES. “That makes me suspicious.” “PISA steadfastly ignored many of these issues,” he says. “I am still concerned.”[62]

Professor Svend Kreiner, of the University of Copenhagen, agreed: “One of the problems that everybody has with PISA is that they don’t want to discuss things with people criticising or asking questions concerning the results. They didn’t want to talk to me at all. I am sure it is because they can’t defend themselves.[62]

United States

Since 2012 a few states have participated in the PISA tests as separate entities. Only the 2012 and 2015 results are available on a state basis. Puerto Rico participated in 2015 as a separate US entity as well.

| Mathematics | Science | Reading | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mathematics | Science | Reading | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

PISA results for the United States by race and ethnicity.

| Mathematics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 2018[63] | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | |

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | ||

| Asian | 539 | 498 | 549 | 524 | 494 | 506 | |

| White | 503 | 499 | 506 | 515 | 502 | 512 | |

| US Average | 478 | 470 | 481 | 487 | 474 | 483 | |

| More than one race | 474 | 475 | 492 | 487 | 482 | 502 | |

| Hispanic | 452 | 446 | 455 | 453 | 436 | 443 | |

| Other | — | 423 | 436 | 460 | 446 | 446 | |

| Black | 419 | 419 | 421 | 423 | 404 | 417 | |

| Science | |||||||

| Race | 2018[63] | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | ||

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | |||

| Asian | 551 | 525 | 546 | 536 | 499 | ||

| White | 529 | 531 | 528 | 532 | 523 | ||

| US Average | 502 | 496 | 497 | 502 | 489 | ||

| More than one race | 502 | 503 | 511 | 503 | 501 | ||

| Hispanic | 478 | 470 | 462 | 464 | 439 | ||

| Other | — | 462 | 439 | 465 | 453 | ||

| Black | 440 | 433 | 439 | 435 | 409 | ||

| Reading | |||||||

| Race | 2018[63] | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | 2000 |

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | |

| Asian | 556 | 527 | 550 | 541 | — | 513 | 546 |

| White | 531 | 526 | 519 | 525 | — | 525 | 538 |

| US Average | 505 | 497 | 498 | 500 | — | 495 | 504 |

| More than one race | 501 | 498 | 517 | 502 | — | 515 | — |

| Hispanic | 481 | 478 | 478 | 466 | — | 453 | 449 |

| Black | 448 | 443 | 443 | 441 | — | 430 | 445 |

| Other | — | 440 | 438 | 462 | — | 456 | 455 |

Research on possible causes of PISA disparities in different countries

Although PISA and TIMSS officials and researchers themselves generally refrain from hypothesizing about the large and stable differences in student achievement between countries, since 2000, literature on the differences in PISA and TIMSS results and their possible causes has emerged.[64] Data from PISA have furnished several researchers, notably Eric Hanushek, Ludger Wößmann, Heiner Rindermann, and Stephen J. Ceci, with material for books and articles about the relationship between student achievement and economic development,[65] democratization, and health;[66] as well as the roles of such single educational factors as high-stakes exams,[67] the presence or absence of private schools and the effects and timing of ability tracking.[68]

Comments on accuracy

David Spiegelhalter of Cambridge wrote: “PISA does present the uncertainty in the scores and ranks – for example the United Kingdom rank in the 65 countries is said to be between 23 and 31. It’s unwise for countries to base education policy on their PISA results, as Germany, Norway and Denmark did after doing badly in 2001.”[69]

According to a Forbes opinion article, some countries such as China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Argentina select PISA samples from only the best-educated areas or from their top-performing students, slanting the results.[70]

According to an open letter to Andreas Schleicher, director of PISA, various academics and educators argued that “OECD and PISA tests are damaging education worldwide”.[71]

According to O Estado de São Paulo, Brazil shows a great disparity when classifying the results between public and private schools, where public schools would rank worse than Peru, while private schools would rank better than Finland.[72]

See also

- Gender gaps in mathematics and reading in PISA 2009

- Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS)

- Teaching And Learning International Survey (TALIS)

- Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)

Explanatory notes References

- ^ “About PISA“. OECD PISA. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Berger, Kathleen (3 March 2014). Invitation to The Life Span (second ed.). worth. ISBN 978-1-4641-7205-2.

- ^ “PISA 2018 Results”. OECD. 3 December 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e “Rey O, ‘The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems’ in CIDREE Yearbook 2010, accessed January 2017”. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ McGaw, B (2008) ‘The role of the OECD in international comparative studies of achievement’ Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 15:3, 223–243

- ^ Mons N, (2008) ‘Évaluation des politiques éducatives et comparaisons internationales’, Revue française de pédagogie, 164, juillet-août-septembre 2008 5–13

- ^ a b c d e f Breakspear, S. (2012). “The Policy Impact of PISA: An Exploration of the Normative Effects of International Benchmarking in School System Performance”. OECD Education Working Paper. OECD Education Working Papers. 71. doi:10.1787/5k9fdfqffr28-en.

- ^ Barroso, J. and de Carvalho, L.M. (2008) ‘PISA: Un instrument de régulation pour relier des mondes’, Revue française de pédagogie, 164, 77–80

- ^ Ertl, H. (2006). “Educational standards and the changing discourse on education: the reception and consequences of the PISA study in Germany”. Oxford Review of Education. 32 (5): 619–634. doi:10.1080/03054980600976320. S2CID 144656964.

- ^ Bajomi, I., Berényi, E., Neumann, E. and Vida, J. (2009). ‘The Reception of PISA in Hungary’ accessed January 2017

- ^ Steiner-Khamsi (2003), cited by Breakspear, S. (2012). “The Policy Impact of PISA: An Exploration of the Normative Effects of International Benchmarking in School System Performance”. OECD Education Working Paper. OECD Education Working Papers. 71. doi:10.1787/5k9fdfqffr28-en.

- ^ Mangez, Eric; Cattonar, Branka (September–December 2009). “The status of PISA in the relationship between civil society and the educational sector in French-speaking Belgium”. Sísifo: Educational Sciences Journal. Educational Sciences R&D Unit of the University of Lisbon (10): 15–26. ISSN 1646-6500. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ “Greger, D. (2008). ‘Lorsque PISA importe peu. Le cas de la République Tchèque et de l’Allemagne’, Revue française de pédagogie, 164, 91–98. cited in Rey O, ‘The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems’ in CIDREE Yearbook 2010, accessed January 2017″. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Afonso, Natércio; Costa, Estela (September–December 2009). “The influence of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) on policy decision in Portugal: the education policies of the 17th Portuguese Constitutional Government” (PDF). Sísifo: Educational Sciences Journal. Educational Sciences R&D Unit of the University of Lisbon (10): 53–64. ISSN 1646-6500. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Rautalin, M.; Alasuutari (2009). “The uses of the national PISA results by Finnish officials in central government”. Journal of Education Policy. 24 (5): 539–556. doi:10.1080/02680930903131267. S2CID 154584726.

- ^ Egelund, N. (2008). ‘The value of international comparative studies of achievement – a Danish perspective’, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 15, 3, 245–251

- ^ “Behrens, 2006 cited in Rey O, ‘The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems in CIDREE Yearbook 2010, accessed January 2017”. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Hefling, Kimberly. “Asian nations dominate international test”. Yahoo!.

- ^ “Chapter 2 of the publication ‘PISA 2003 Assessment Framework'” (PDF). PISA.oecd.org.

- ^ Keeley B. PISA, we have a problem… OECD Insights, April 2014.

- ^ Poddiakov, Alexander Complex Problem Solving at PISA 2012 and PISA 2015: Interaction with Complex Reality. // Translated from Russian. Reference to the original Russian text: Poddiakov, A. (2012.) Reshenie kompleksnykh problem v PISA-2012 i PISA-2015: vzaimodeistvie so slozhnoi real’nost’yu. Obrazovatel’naya Politika, 6, 34–53.

- ^ C. Füller: PISA hat einen kleinen, fröhlichen Bruder. taz, 5.12.2007 [1]

- ^ Stanat, P; Artelt, C; Baumert, J; Klieme, E; Neubrand, M; Prenzel, M; Schiefele, U; Schneider, W (2002), PISA 2000: Overview of the study—Design, method and results, Berlin: Max Planck Institute for Human Development

- ^ Mazzeo, John; von Davier, Matthias (2013), Linking Scales in International Large-Scale Assessments, chapter 10 in Rutkowski, L. von Davier, M. & Rutkowski, D. (eds.) Handbook of International Large-Scale Assessment: Background, Technical Issues, and Methods of Data Analysis., New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- ^ von Davier, Matthias; Sinharay, Sandip (2013), Analytics in International Large-Scale Assessments: Item Response Theory and Population Models, chapter 7 in Rutkowski, L. von Davier, M. & Rutkowski, D. (eds.) Handbook of International Large-Scale Assessment: Background, Technical Issues, and Methods of Data Analysis., New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- ^ PISA 2018: Insights and Interpretations (PDF), OECD, 3 December 2019, retrieved 4 December 2019

- ^ PISA 2018 in Spain (PDF), OECD, 15 November 2019, retrieved 28 February 2021

- ^ Baldi, Stéphane; Jin, Ying; Skemer, Melanie; Green, Patricia J; Herget, Deborah; Xie, Holly (10 December 2007), Highlights From PISA 2006: Performance of U.S. 15-Year-Old Students in Science and Mathematics Literacy in an International Context (PDF), NCES, retrieved 14 December 2013, PISA 2006 reading literacy results are not reported for the United States because of an error in printing the test booklets. Furthermore, as a result of the printing error, the mean performance in mathematics and science may be misestimated by approximately 1 score point. The impact is below one standard error.

- ^ PISA 2009 Results: Executive Summary (PDF), OECD, 7 December 2010

- ^ ACER releases results of PISA 2009+ participant economies, ACER, 16 December 2011, archived from the original on 14 December 2013

- ^ Walker, Maurice (2011), PISA 2009 Plus Results (PDF), OECD, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2011, retrieved 28 June 2012

- ^ PISA 2012 Results in Focus (PDF), OECD, 3 December 2013, retrieved 4 December 2013

- ^ Tom Phillips (3 December 2013) OECD education report: Shanghai’s formula is world-beating The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 December 2013

- ^ a b Cook, Chris (7 December 2010), “Shanghai tops global state school rankings”, Financial Times, retrieved 28 June 2012

- ^ Mance, Henry (7 December 2010), “Why are Chinese schoolkids so good?”, Financial Times, retrieved 28 June 2012

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (26 August 2014). “PISA tests to include many more Chinese pupils”. BBC News.

- ^ Helen Gao, “Shanghai Test Scores and the Mystery of the Missing Children”, New York Times, January 23, 2014. For Schleicher’s initial response to these criticisms see his post, “Are the Chinese Cheating in PISA Or Are We Cheating Ourselves?” on the OECD’s website blog, Education Today, December 10, 2013.

- ^ “William Stewart, “More than a quarter of Shanghai pupils missed by international PISA rankings”, Times Educational Supplement, March 6, 2014″. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ http://www.oecd.org/china/Education-in-China-a-snapshot.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Howse, Patrick (18 February 2014). “Shanghai visit for minister to learn maths lessons”. BBC News. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (12 March 2014). “Shanghai teachers flown in for maths”. BBC News. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ “Britain invites 120 Chinese Maths teachers for aided schools”. India Today. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ “Scores bolster case for Shanghai math in British schools | The Star”. www.thestar.com.my. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Turner, Camilla (3 December 2019). “Britain jumps up international maths rankings following Chinese-style teaching”. The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Starkey, Hannah (5 December 2019). “UK Boost International Maths Ranking After Adopting Chinese-Style Teaching”. True Education Partnerships. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ PISA 2012: Proficiency of Finnish youth declining University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved 9 December 2013

- ^ Hemali Chhapia, TNN (3 August 2012). “India backs out of global education test for 15-year-olds”. The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013.

- ^ “Poor PISA score: Govt blames ‘disconnect’ with India”. The Indian Express. 3 September 2012.

- ^ “India chickens out of international students assessment programme again”. The Times of India. 1 June 2013.

- ^ “PISA Tests: India to take part in global teen learning test in 2021″. The Indian Express. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ “Ong: Did ministry try to rig results for PISA 2015 report?”. 8 December 2016.

- ^ “Who’s telling the truth about M’sia’s PISA 2015 scores?”. 9 December 2016.

- ^ “Malaysian PISA results under scrutiny for lack of evidence – School Advisor”. 8 December 2016.

- ^ Lars Näslund (3 December 2013) Svenska skolan rasar i stor jämförelse Expressen. Retrieved 4 December 2013 (in Swedish)

- ^ a b Jens Kärrman (3 December 2013) Löfven om PISA: Nationell kris Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 8 December 2013 (in Swedish)

- ^ “Sveriges PISA-framgång bygger på falska siffror”.

- ^ a b Adams, Richard (3 December 2013), “UK students stuck in educational doldrums, OECD study finds”, The Guardian, retrieved 4 December 2013

- ^ PISA ranks Wales’ education the worst in the UK BBC. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (3 December 2013) Ambrose Evans-Pritchard Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ “William Stewart, “Is PISA fundamentally flawed?” Times Educational Supplement, July 26, 2013″. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Morrison, Hugh (2013). “A fundamental conundrum in psychology’s standard model of measurement and its consequences for PISA global rankings” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ a b Stewart, “Is PISA fundamentally flawed?” TES (2013).

- ^ a b c “Highlights of U.S. PISA 2018 Results Web Report” (PDF).{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

- ^ Hanushek, Eric A., and Ludger Woessmann. 2011. “The economics of international differences in educational achievement.” In Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 3, edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin, and Ludger Woessmann. Amsterdam: North Holland: 89–200.

- ^ Hanushek, Eric; Woessmann, Ludger (2008), “The role of cognitive skills in economic development” (PDF), Journal of Economic Literature, 46 (3): 607–668, doi:10.1257/jel.46.3.607

- ^ Rindermann, Heiner; Ceci, Stephen J (2009), “Educational policy and country outcomes in international cognitive competence studies”, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4 (6): 551–577, doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01165.x, PMID 26161733, S2CID 9251473

- ^ Bishop, John H (1997). “The effect of national standards and curriculum-based exams on achievement”. American Economic Review. Papers and Proceedings. 87 (2): 260–264. JSTOR 2950928.

- ^ Hanushek, Eric; Woessmann, Ludger (2006), “Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries” (PDF), Economic Journal, 116 (510): C63–C76, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x

- ^ Alexander, Ruth (10 December 2013). “How accurate is the PISA test?”. BBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Flows, Capital. “Are The PISA Education Results Rigged?”. Forbes. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Guardian Staff (6 May 2014). “OECD and PISA tests are damaging education worldwide – academics”. Retrieved 22 November 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Cafardo, Rafael (4 décembre 2019). “Escolas privadas de elite do Brasil superam Finlândia no PISA, rede pública vai pior do que o Peru” . Récupéré le 4 décembre 2019 – via www.estadao.com.br.

Liens externes

- Site Web de l’OCDE/PISA

- OCDE (1999) : Mesurer les connaissances et compétences des élèves : un nouveau cadre d’évaluation . Paris : OCDE, ISBN 92-64-17053-7

- OCDE (2014) : Résultats du PISA 2012 : Résolution créative de problèmes : Compétences des élèves pour résoudre des problèmes de la vie réelle (Volume V) [2]

- GPS de l’éducation de l’OCDE : données interactives du PISA 2015

- Explorateur de données PISA

- Gunda Tire : « Les Estoniens croient en l’éducation, et cette croyance a été essentielle pendant des siècles » — Interview de Gunda Tire, responsable du projet national PISA de l’OCDE, pour Caucasian Journal