Présidence de Donald Trump

Le mandat de Donald Trump en tant que 45e président des États-Unis a commencé avec son investiture le 20 janvier 2017 et s’est terminé le 20 janvier 2021. Trump, un républicain de New York , a pris ses fonctions après la victoire de son collège électoral sur le candidat démocrate . Hillary Clinton lors de l’ élection présidentielle de 2016 , au cours de laquelle il n’a pas remporté la majorité des suffrages exprimés. Trump a fait un nombre sans précédent de déclarations fausses ou trompeuses au cours de sa campagne et de sa présidence. Sa présidence s’est soldée par une défaite à l’ élection présidentielle de 2020Le démocrate Joe Biden après un mandat. C’était la première présidence depuis celle d’ Herbert Hoover en 1932 au cours de laquelle un président en exercice était défait et son parti perdait ses majorités dans les deux chambres du Congrès. [1]

|

|

| Présidence de Donald Trump 20 janvier 2017 – 20 janvier 2021 |

|

| Cabinet | Voir la liste |

|---|---|

| Faire la fête | Républicain |

| Élection | 2016 |

| Siège | maison Blanche |

| ← Barack Obama Joe Biden → | |

Sceau du président |

|

| Site Web archivé Site Web de la bibliothèque |

Trump a échoué dans ses efforts pour abroger la loi sur les soins abordables (ACA), mais a annulé le mandat individuel et a pris des mesures pour entraver le fonctionnement de l’ACA. Trump a cherché à réduire considérablement les dépenses des principaux programmes de protection sociale, notamment Medicare et Medicaid . Il a signé le Great American Outdoors Act , annulé de nombreuses réglementations environnementales et s’est retiré de l ‘ Accord de Paris sur le changement climatique . Il a signé la réforme de la justice pénale par le biais du First Step Act et a nommé avec succès Neil Gorsuch ,Brett Kavanaugh et Amy Coney Barrett à la Cour suprême . En politique économique, il a partiellement abrogé la loi Dodd-Frank et signé la loi de 2017 sur les réductions d’impôts et l’emploi . Il a promulgué des tarifs douaniers , déclenchant des représailles tarifaires de la part de la Chine , du Canada, du Mexique et de l’UE. Il s’est retiré des négociations du Partenariat transpacifique et a signé l’ USMCA , un accord qui succède à l’ ALENA . Le déficit fédéral a augmenté sous Trump en raison de l’augmentation des dépenses et des réductions d’impôts.

Il a mis en place une politique controversée de séparation des familles pour les migrants appréhendés à la frontière américano-mexicaine. La demande de Trump pour le financement fédéral d’ un mur frontalier a entraîné la plus longue fermeture du gouvernement américain de l’histoire . Il a déployé les forces fédérales d’application de la loi en réponse aux troubles raciaux en 2020 . La politique étrangère « America First » de Trump s’est caractérisée par des actions unilatérales, sans tenir compte des alliés traditionnels. L’administration a mis en place une importante vente d’armes à l’Arabie saoudite ; a refusé aux citoyens de plusieurs pays à majorité musulmane l’ entrée aux États-Unis ;reconnu Jérusalem comme capitale d’Israël ; et a négocié les Accords d’Abraham , une série d’ accords de normalisation entre Israël et divers États arabes . Son administration a retiré les troupes américaines du nord de la Syrie, permettant à la Turquie d’occuper la région . Son administration a également conclu un accord conditionnel avec les talibans pour retirer les troupes américaines d’Afghanistan en 2021 . Trump a rencontré trois fois le dirigeant nord-coréen Kim Jong-un . Trump a retiré les États-Unis de l’accord nucléaire iranien et a ensuite aggravé les tensions dans le golfe Persique enordonnant l’assassinat du général Qasem Soleimani .

L’ enquête du conseil spécial de Robert Mueller (2017-2019) a conclu que la Russie était intervenue pour favoriser la candidature de Trump et que, bien que les preuves en vigueur “n’établissent pas que les membres de la campagne Trump ont conspiré ou se sont coordonnés avec le gouvernement russe”, d’éventuelles entraves à la justice se sont produites. au cours de cette enquête.

Trump a tenté de faire pression sur l’Ukraine pour qu’elle annonce des enquêtes sur son rival politique Joe Biden, déclenchant sa première destitution par la Chambre des représentants le 18 décembre 2019, mais il a été acquitté par le Sénat le 5 février 2020.

Trump a réagi lentement à la pandémie de COVID-19 , a ignoré ou contredit de nombreuses recommandations des responsables de la santé dans ses messages et a promu la désinformation sur les traitements non éprouvés et la disponibilité des tests.

Après sa défaite à l’ élection présidentielle de 2020 face à Biden, Trump a refusé de céder et a lancé une vaste campagne pour annuler les résultats , faisant de fausses allégations de fraude électorale généralisée . Le 6 janvier 2021, lors d’un rassemblement à l’Ellipse , Trump a exhorté ses partisans à “se battre comme un diable” et à marcher vers le Capitole , où les votes électoraux étaient comptés par le Congrès afin d’officialiser la victoire de Biden. Une foule de partisans de Trump a pris d’assaut le Capitole , suspendant le décompte et provoquant l’évacuation du vice-président Mike Pence et d’autres membres du Congrès. Le 13 janvier, la Chambre a votédestituer Trump une seconde fois sans précédent pour « incitation à l’insurrection », mais il a ensuite été de nouveau acquitté par le Sénat le 13 février, alors qu’il avait déjà quitté ses fonctions. Trump avait des taux d’approbation historiquement bas, et les universitaires et les historiens classent sa présidence comme l’une des pires de l’histoire américaine.

élection 2016

L’élection présidentielle de 2016. Cinq personnes en plus de Trump et Clinton ont reçu des votes électoraux d’ électeurs infidèles .

L’élection présidentielle de 2016. Cinq personnes en plus de Trump et Clinton ont reçu des votes électoraux d’ électeurs infidèles .

Le 9 novembre 2016, les républicains Donald Trump de New York et le gouverneur Mike Pence de l’Indiana ont remporté les élections de 2016 , battant l’ancienne secrétaire d’État démocrate Hillary Clinton de New York et le sénateur Tim Kaine de Virginie. Trump a remporté 304 votes électoraux contre 227 pour Clinton, bien que Clinton ait remporté une pluralité de votes populaires, recevant près de 2,9 millions de votes de plus que Trump. Trump est ainsi devenu la cinquième personne à remporter la présidence tout en perdant le vote populaire . [2] Lors des élections législatives simultanées, les républicains ont maintenu la majorité à la fois à la Chambre des représentants et à laSénat .

Période de transition, inauguration et 100 premiers jours

Le président sortant Barack Obama et le président élu Donald Trump dans le bureau ovale le 10 novembre 2016

Le président sortant Barack Obama et le président élu Donald Trump dans le bureau ovale le 10 novembre 2016

Portrait officiel de Donald Trump avant sa prestation de serment.

Portrait officiel de Donald Trump avant sa prestation de serment.

Cérémonie d’investiture

Cérémonie d’investiture

Trump a été inauguré le 20 janvier 2017. Il a été assermenté par le juge en chef John Roberts . [3] Dans son discours inaugural de dix-sept minutes, Trump a brossé un tableau sombre de l’Amérique contemporaine, s’engageant à mettre fin au “carnage américain” causé par la criminalité urbaine et affirmant que “la richesse, la force et la confiance de l’Amérique se sont dissipées” par les emplois perdus à l’étranger. [4] Il a déclaré que sa stratégie serait « l’ Amérique d’abord ». [3] La plus grande manifestation d’une journée de l’histoire des États-Unis, la Marche des femmes , a eu lieu le lendemain de son investiture et a été motivée par l’opposition à Trump et à ses politiques et opinions. [5]

L’une des principales réalisations de Trump la première année, dans le cadre d’un “engagement de 100 jours”, a été la confirmation de Neil Gorsuch en tant que juge associé de la Cour suprême . Bien que le Parti républicain détienne la majorité dans les deux chambres du Congrès, il n’a cependant pas été en mesure de tenir une autre promesse de cent jours, abrogeant la loi sur les soins abordables (“Obamacare”). [6]

Administration

| Le Cabinet Trump | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bureau | Nom | Terme |

| Président | Donald Trump | 2017–2021 |

| Vice président | Mike Pence | 2017–2021 |

| secrétaire d’État | Rex Tillerson | 2017-2018 |

| Mike Pompeo | 2018–2021 | |

| Secrétaire au Trésor | Steven Mnuchin | 2017–2021 |

| secrétaire de la Défence | Jim Mattis | 2017–2019 |

| Marc Esper | 2019–2020 | |

| procureur général | Jeff Séances | 2017-2018 |

| Guillaume Barr | 2019–2020 | |

| secrétaire de l’intérieur | Ryan Zinke | 2017–2019 |

| David Bernhard | 2019–2021 | |

| Secrétaire de l’Agriculture | Sonny perdu | 2017–2021 |

| secrétaire du commerce | Wilbur Ross | 2017–2021 |

| Secrétaire du travail | Alexandre Acosta | 2017–2019 |

| Eugène Scalia | 2019–2021 | |

| Secrétaire à la Santé et aux Services sociaux |

Tom Prix | 2017 |

| Alex Azar | 2018–2021 | |

| Secrétaire au logement et au développement urbain |

Ben Carson | 2017–2021 |

| Secrétaire aux transports | Elaine Chao | 2017–2021 |

| Secrétaire à l’énergie | Rick Perry | 2017–2019 |

| Dan Brouillette | 2019–2021 | |

| Secrétaire à l’éducation | Betsy DeVos | 2017–2021 |

| Secrétaire aux Anciens Combattants | David Shulkin | 2017-2018 |

| Robert Wilkie | 2018–2021 | |

| Secrétaire à la sécurité intérieure | John F.Kelly | 2017 |

| Kirstjen Nielsen | 2017–2019 | |

| Chad Wolf (par intérim) | 2019–2021 | |

| Administrateur de l’ Agence de protection de l’environnement |

Scott Pruitt | 2017-2018 |

| Andrew Wheeler | 2018–2021 | |

| directeur du bureau de gestion et du budget |

Mick Mulvaney | 2017–2020 |

| Russel Vought | 2020–2021 | |

| Directeur du renseignement national | Manteaux Dan | 2017–2019 |

| Jean Ratcliffe | 2020–2021 | |

| directeur de la Agence centrale de renseignement |

Mike Pompeo | 2017-2018 |

| Gina Haspel | 2018–2021 | |

| Représentant commercial des États-Unis | Robert Lighthizer | 2017–2021 |

| Ambassadeur aux Nations Unies | Nikki Haley | 2017-2018 |

| Kelly Artisanat | 2019–2021 | |

| Administrateur de la Small Business Administration |

Linda Mc Mahon | 2017–2019 |

| Jovita Carranza | 2020–2021 | |

| Chef d’équipe | Reine Priebus | 2017 |

| John F.Kelly | 2017–2019 | |

| Marquer les prés | 2020–2021 |

L’administration Trump a été caractérisée par un roulement record, en particulier parmi le personnel de la Maison Blanche. Début 2018, 43% des postes de direction de la Maison Blanche avaient été remplacés. [7] L’administration a eu un taux de roulement plus élevé au cours des deux premières années et demie que les cinq présidents précédents pendant l’ensemble de leur mandat. [8]

En octobre 2019, un sur 14 des personnes nommées par Trump était d’anciens lobbyistes ; moins de trois ans après le début de sa présidence, Trump avait nommé plus de quatre fois plus de lobbyistes qu’Obama au cours de ses six premières années au pouvoir. [9]

Les nominations au Cabinet de Trump comprenaient le sénateur américain de l’Alabama Jeff Sessions en tant que procureur général , [10] le banquier Steve Mnuchin en tant que secrétaire au Trésor , [11] le général à la retraite du Corps des Marines James Mattis en tant que secrétaire à la Défense , [12] et le PDG d’ ExxonMobil , Rex Tillerson , en tant que secrétaire d’État . [13] Trump a également recruté des politiciens qui s’étaient opposés à lui pendant la campagne présidentielle, comme le neurochirurgien Ben Carson en tant que secrétaire au logement et au développement urbain ,[14] et le gouverneur de Caroline du Sud, Nikki Haley , comme ambassadeur aux Nations Unies . [15]

Conseil des ministres, mars 2017

Conseil des ministres, mars 2017

Cabinet

Quelques jours après l’élection présidentielle, Trump a choisi le président du RNC, Reince Priebus , comme chef de cabinet . [16] Trump a choisi le sénateur de l’Alabama Jeff Sessions pour le poste de procureur général. [17]

En février 2017, Trump a officiellement annoncé la structure de son cabinet, élevant le directeur du renseignement national et le directeur de la CIA au niveau du cabinet. Le président du Conseil des conseillers économiques , qui avait été ajouté au cabinet par Obama en 2009, a été retiré du cabinet. Le cabinet de Trump était composé de 24 membres, plus qu’Obama à 23 ans ou George W. Bush à 21 ans. [18]

Le 13 février 2017, Trump a renvoyé Michael Flynn du poste de conseiller à la sécurité nationale au motif qu’il avait menti au vice-président Pence au sujet de ses communications avec l’ambassadeur russe Sergey Kislyak ; Flynn a par la suite plaidé coupable d’avoir menti au Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) au sujet de ses contacts avec la Russie. [19] Flynn a été licencié au milieu de la controverse en cours concernant l’ingérence russe dans les élections de 2016 et les accusations selon lesquelles l’équipe électorale de Trump était de connivence avec des agents russes.

En juillet 2017, John F. Kelly , qui avait été secrétaire de la Sécurité intérieure , a remplacé Priebus au poste de chef de cabinet. [20] En septembre 2017, Tom Price a démissionné de son poste de secrétaire du HHS au milieu des critiques concernant son utilisation de jets charter privés pour ses voyages personnels. [21] Kirstjen Nielsen a succédé à Kelly au poste de secrétaire en décembre 2017. [22] Le secrétaire d’État Rex Tillerson a été limogé via un tweet en mars 2018 ; Trump a nommé Mike Pompeo pour remplacer Tillerson et Gina Haspel pour succéder à Pompeo en tant que directeur de la CIA.[23]À la suite d’une série de scandales, Scott Pruitt a démissionné de son poste d’ administrateur de l’ Agence de protection de l’environnement (EPA) en juillet 2018. [24] Le secrétaire à la Défense, Jim Mattis, a informé Trump de sa démission à la suite de l’annonce brutale de Trump le 19 décembre les 2 000 soldats américains restants en Syrie seraient retirés, contre les recommandations de ses conseillers militaires et civils. [25]

Trump a limogé de nombreux inspecteurs généraux d’agences, y compris ceux qui sondaient l’administration Trump et ses proches associés. En 2020, il a licencié cinq inspecteurs généraux en deux mois. Le Washington Post a écrit: “Pour la première fois depuis la création du système à la suite du scandale du Watergate, les inspecteurs généraux se retrouvent systématiquement attaqués par le président, mettant en danger la surveillance indépendante des dépenses et des opérations fédérales.” [26]

Licenciement de James Comey

Trump a limogé le directeur du FBI, James Comey , le 9 mai 2017, affirmant qu’il avait accepté les recommandations du procureur général Sessions et du sous-procureur général Rod Rosenstein de renvoyer Comey. La recommandation de Sessions était basée sur celle de Rosenstein, tandis que Rosenstein écrivait que Comey devait être renvoyé pour sa gestion de la conclusion de l’enquête du FBI sur la controverse sur les e-mails d’Hillary Clinton . [27] Le 10 mai, Trump a rencontré le ministre russe des Affaires étrangères Sergueï Lavrov et l’ambassadeur russe Sergueï Kislyak . Sur la base des notes de la réunion de la Maison Blanche , Trump a déclaré aux Russes : “Je viens de virer le chef du FBI. Il était fou, un vrai taré. de la Maison Blanche … J’ai subi une grande pression à cause de la Russie. C’est enlevé.” [28] Le 11 mai, Trump a déclaré dans une interview vidéo, “… quelle que soit la recommandation, j’allais virer Comey … en fait, quand j’ai décidé de le faire, j’ai dit à moi-même, j’ai dit, vous savez, cette affaire de Russie avec Trump et la Russie est une histoire inventée.” [29] Le 18 mai, Rosenstein a déclaré aux membres du Sénat américain qu’il avait recommandé le renvoi de Comey tout en sachant que Trump avait déjà décidé de licencier Comey [30] Au lendemain du licenciement de Comey, les événements ont été comparés à ceux du « massacre du samedi soir » sous l’administration de Richard Nixon et il y a eu un débat sur la question de savoir si Trump avait provoqué uncrise constitutionnelle , car il avait limogé l’homme qui menait une enquête sur les associés de Trump. [31] Les déclarations de Trump ont soulevé des inquiétudes quant à une éventuelle obstruction à la justice. [32] Dans la note de Comey sur une réunion de février 2017 avec Trump , Comey a déclaré que Trump avait tenté de le persuader d’interrompre l’enquête sur le général Flynn. [33]

Nominations judiciaires

La candidate à la Cour suprême Amy Coney Barrett et sa famille avec Trump le 26 septembre 2020

La candidate à la Cour suprême Amy Coney Barrett et sa famille avec Trump le 26 septembre 2020

Les républicains du Sénat, dirigés par le chef de la majorité au Sénat, Mitch McConnell , ont donné la priorité à la confirmation des nominations judiciaires de Trump, le faisant rapidement. [34] En novembre 2018, Trump avait nommé 29 juges aux cours d’appel américaines , plus que n’importe quel président moderne au cours des deux premières années d’un mandat présidentiel. [35] Trump a finalement nommé 226 juges fédéraux de l’article III et 260 juges fédéraux au total. [36] Ses personnes nommées, qui étaient généralement affiliées à la société fédérale conservatrice , ont déplacé le système judiciaire vers la droite . [37]Un tiers des personnes nommées par Trump avaient moins de 45 ans lors de leur nomination, bien plus que sous les présidents précédents. [37] Les candidats à la magistrature de Trump étaient moins susceptibles d’être des femmes ou des minorités ethniques que ceux de l’administration précédente. [38] [39] Parmi les nominations judiciaires de Trump aux cours d’appel américaines (courts de circuit), les deux tiers étaient des hommes blancs, contre 31 % des candidats d’Obama et 63 % des candidats de George W. Bush. [37] [40]

Nominations à la Cour suprême

Trump a fait trois nominations à la Cour suprême : Neil Gorsuch , Brett Kavanaugh et Amy Coney Barrett :

- Trump a nommé Neil Gorsuch en janvier 2017 pour combler le poste laissé vacant par la mort du juge Antonin Scalia en février 2016, qui n’avait pas été pourvu par Obama car le Sénat à majorité républicaine n’a pas envisagé la nomination de Merrick Garland . Gorsuch a été confirmé en avril 2017 lors d’un vote majoritairement partisan de 54 à 45. [41]

- Trump a nommé Brett Kavanaugh en juillet 2018 pour remplacer le juge à la retraite Anthony Kennedy , qui était considéré comme un vote clé à la Cour suprême. Le Sénat a confirmé Kavanaugh lors d’un vote majoritairement partisan de 50 à 48 en août 2018 après des allégations selon lesquelles Kavanaugh avait tenté de violer un autre élève alors qu’ils étaient tous les deux au lycée; Kavanaugh a nié l’allégation. [42] [43]

- Trump a nommé Amy Coney Barrett en septembre 2020 pour combler le poste laissé vacant par le décès de la juge Ruth Bader Ginsburg . Ginsburg était considérée comme faisant partie de l’aile libérale de la Cour et son remplacement par un juriste conservateur a considérablement modifié la composition idéologique de la Cour suprême . [44] Les démocrates se sont opposés à la nomination, arguant que le poste vacant à la cour ne devrait pas être pourvu avant l’ élection présidentielle de 2020 . Le 26 octobre 2020, le Sénat a confirmé Barrett par un vote majoritairement partisan de 52 à 48, tous les démocrates s’opposant à sa confirmation. [45]

Style de leadership

Les propres membres du personnel, subordonnés et alliés de Trump ont souvent qualifié Trump d’infant. [46] Trump aurait évité de lire des documents d’information détaillés, y compris le President’s Daily Brief , en faveur de recevoir des informations orales. [47] [48] Les informateurs du renseignement auraient répété le nom et le titre du président afin de retenir son attention. [49] [50] Il était également connu pour acquérir des informations en regardant jusqu’à huit heures de télévision chaque jour, notamment des programmes de Fox News tels que Fox & Friends et Hannity , dont les points de discussion diffusés par Trump étaient parfois répétés dans des déclarations publiques, en particulier dans tweets du matin. [51][52] [53] Trump aurait exprimé sa colère si les analyses du renseignement contredisaient ses croyances ou ses déclarations publiques, deux informateurs déclarant qu’ils avaient été chargés par leurs supérieurs de ne pas fournir à Trump des informations qui contredisaient ses déclarations publiques. [50]

Trump aurait favorisé le chaos en tant que technique de gestion, entraînant un moral bas et une confusion politique parmi son personnel. [54] [55] Trump s’est avéré incapable de faire un compromis efficace lors du 115e Congrès américain , ce qui a conduit à une impasse gouvernementale importante et à quelques réalisations législatives notables malgré le contrôle républicain des deux chambres du Congrès. [56] L’historienne présidentielle Doris Kearns Goodwin a découvert que Trump manquait de plusieurs traits d’un leader efficace, notamment “l’humilité, la reconnaissance des erreurs, le blâme et l’apprentissage des erreurs, l’empathie, la résilience, la collaboration, la connexion avec les gens et le contrôle des émotions improductives”. [57]

En janvier 2018, Axios a rapporté que les heures de travail de Trump étaient généralement d’environ 11h00 à 18h00 . (un début plus tardif et une fin plus précoce par rapport au début de sa présidence) et qu’il tenait moins de réunions pendant ses heures de travail afin de répondre au désir de Trump d’avoir plus de temps libre non structuré (appelé «temps exécutif»). [58] En 2019, Axios a publié l’horaire de Trump du 7 novembre 2018 au 1er février 2019 et a calculé qu’environ soixante pour cent du temps entre 8h00 et 17h00 . était le “temps exécutif”. [59]

Déclarations fausses et trompeuses

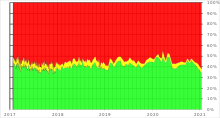

Les vérificateurs des faits du Washington Post , [60] (orange) du Toronto Star , [61] et de CNN [62] (bleu) ont compilé des données sur les “allégations fausses ou trompeuses” et les “allégations mensongères”, respectivement. Les pics fin 2018 correspondent aux élections de mi-mandat , fin 2019 à son enquête de destitution , et fin 2020 à la présidentielle. Le Post a signalé 30 573 déclarations fausses ou trompeuses en 4 ans, [60] une moyenne de plus de 20,9 par jour.

Les vérificateurs des faits du Washington Post , [60] (orange) du Toronto Star , [61] et de CNN [62] (bleu) ont compilé des données sur les “allégations fausses ou trompeuses” et les “allégations mensongères”, respectivement. Les pics fin 2018 correspondent aux élections de mi-mandat , fin 2019 à son enquête de destitution , et fin 2020 à la présidentielle. Le Post a signalé 30 573 déclarations fausses ou trompeuses en 4 ans, [60] une moyenne de plus de 20,9 par jour.

Le nombre et l’ampleur des déclarations de Trump dans les discours publics, les remarques et les tweets identifiés comme faux par les universitaires, les vérificateurs de faits et les commentateurs ont été qualifiés de sans précédent pour un président américain [63] [64] et même sans précédent dans la politique américaine. [65] Le New Yorker a appelé les mensonges une partie distinctive de son identité politique, [66] et ils ont également été décrits par la conseillère politique républicaine Amanda Carpenter comme une tactique d’ éclairage au gaz. [67] Sa Maison Blanche avait rejeté l’idée de vérité objective [68] et sa campagne et sa présidence ont été décrites comme étant ” post-vérité» [69]et hyper- orwellienne . [70] La signature rhétorique de Trump comprenait le fait de ne pas tenir compte des données des institutions fédérales qui étaient incompatibles avec ses arguments ; de citer des ouï-dire, des preuves anecdotiques et des affirmations douteuses dans les médias partisans ; de nier la réalité (y compris ses propres déclarations) ; et de distraire quand des mensonges ont été exposés. [71]

Au cours de la première année de la présidence de Trump, l’ équipe de vérification des faits du Washington Post a écrit que Trump était “le politicien le plus contesté par les faits” qu’il ait “jamais rencontré … le rythme et le volume des déclarations inexactes du président signifient que nous ne pouvons pas continuez.” [72] En tant que président, Trump a fait plus de 5 000 déclarations fausses ou trompeuses en septembre 2018, [73] et en avril 2020, Trump avait fait 18 000 déclarations fausses ou trompeuses pendant son mandat, soit une moyenne de plus de 15 déclarations par jour. [74] Le taux de déclarations fausses et trompeuses de Trump a augmenté dans les semaines précédant les élections de mi-mandat de 2018 [75] et au premier semestre 2020. [74] Les affirmations fausses ou trompeuses les plus courantes de Trump concernaient l’économie et l’emploi, sa proposition de mur frontalier et sa législation fiscale ; [74] il avait également fait de fausses déclarations concernant les administrations précédentes [74] ainsi que d’autres sujets, notamment la criminalité, le terrorisme, l’immigration, la Russie et l’enquête Mueller, l’ enquête ukrainienne , l’immigration et la pandémie de COVID-19 . [60] Les hauts fonctionnaires de l’administration avaient également régulièrement fait des déclarations fausses, trompeuses ou torturées aux médias d’information, [76] [77] ce qui rendait difficile pour les médias d’information de prendre au sérieux les déclarations officielles. [76]

Règle de loi

Peu de temps avant que Trump n’obtienne l’investiture républicaine de 2016, le New York Times a rapporté que “des experts juridiques de tous les horizons politiques disent que” la rhétorique de Trump reflète “une vision constitutionnelle du monde qui méprise le premier amendement, la séparation des pouvoirs et l’état de droit”, ajoutant “De nombreux juristes conservateurs et libertaires avertissent que l’élection de M. Trump est la recette d’une crise constitutionnelle.” [78] Les politologues ont averti que la rhétorique et les actions du candidat Trump imitaient celles d’autres politiciens qui sont finalement devenus autoritaires une fois au pouvoir. [79] Certains chercheurs ont conclu que pendant le mandat de Trump en tant que président et en grande partie en raison de ses actions et de sa rhétorique, les États-Unis ont connu. [80] De nombreux républicains éminents ont exprimé des inquiétudes similaires selon lesquelles le mépris perçu de Trump pour l’état de droit trahissait les principes conservateurs. [82] [83] [84] [85]

Au cours des deux premières années de sa présidence, Trump a cherché à plusieurs reprises à influencer le ministère de la Justice pour enquêter sur ses adversaires politiques – en particulier Hillary Clinton, le Comité national démocrate et le directeur du FBI James Comey, qu’il considérait comme son adversaire. Il a constamment répété une variété d’allégations, dont au moins certaines avaient déjà fait l’objet d’une enquête ou avaient été réfutées. [86] [87] Au printemps 2018, Trump a déclaré à l’avocat de la Maison Blanche, Don McGahn , qu’il voulait ordonner au DOJ de poursuivre Clinton et Comey, mais McGahn a informé Trump qu’une telle action constituerait un abus de pouvoir et inviterait à une éventuelle destitution . [88]En mai 2018, Trump a exigé que le DOJ enquête « pour savoir si le FBI / DOJ a infiltré ou surveillé la campagne Trump à des fins politiques », ce que le DOJ a renvoyé à son inspecteur général. [89] Bien qu’il ne soit pas illégal pour un président d’exercer une influence sur le DOJ pour ouvrir une enquête, les présidents ont assidûment évité de le faire pour éviter les perceptions d’ingérence politique. [89] [90]

Le procureur général Jeff Sessions a résisté à plusieurs demandes de Trump et de ses alliés d’enquêter sur des opposants politiques, ce qui a amené Trump à exprimer à plusieurs reprises sa frustration, déclarant à un moment donné : “Je n’ai pas de procureur général”. [91] Tout en critiquant l’enquête de l’avocat spécial en juillet 2019, Trump a faussement affirmé que la Constitution garantit que « j’ai le droit de faire ce que je veux en tant que président ». [92] Trump avait à plusieurs reprises suggéré ou promu l’idée de prolonger sa présidence au-delà des limites normales du mandat. [93] [94]

Trump a fréquemment critiqué l’indépendance du pouvoir judiciaire pour ingérence injuste dans la capacité de son administration à décider de la politique. [95] En novembre 2018, dans une réprimande extraordinaire d’un président en exercice, le juge en chef de la Cour suprême, John Roberts , a critiqué la caractérisation par Trump d’un juge qui avait statué contre sa politique en tant que “juge Obama”, ajoutant “Ce n’est pas la loi”. [96] En octobre 2020, vingt anciens avocats républicains américains , qui ont été nommés par chaque président du GOP datant d’Eisenhower, ont qualifié Trump de “menace pour l’état de droit dans notre pays”.Greg Brower, qui a travaillé dans l’administration Trump, a affirmé : “Il est clair que le président Trump considère le ministère de la Justice et le FBI comme son propre cabinet d’avocats et son agence d’enquête.” [97]

Relation avec les médias d’information

Trump parle à la presse dans le bureau ovale le 21 mars 2017, avant de signer S.422 (la NASA Transition Authorization Act)

Trump parle à la presse dans le bureau ovale le 21 mars 2017, avant de signer S.422 (la NASA Transition Authorization Act)

Trump s’adresse aux journalistes sur la pelouse sud de la Maison Blanche en juin 2019

Trump s’adresse aux journalistes sur la pelouse sud de la Maison Blanche en juin 2019

Au début de sa présidence, Trump a développé une relation très controversée avec les médias d’information, les qualifiant à plusieurs reprises de « faux médias d’information » et « d’ennemis du peuple ». [98] En tant que candidat, Trump avait refusé les autorisations de presse pour les publications offensantes, mais a déclaré qu’il ne le ferait pas s’il était élu. [99] Trump a songé à la fois en privé et en public à retirer les références de presse de la Maison Blanche aux journalistes critiques . [100] Dans le même temps, la Maison Blanche de Trump a accordé des laissez-passer de presse temporaires à des médias d’extrême droite pro-Trump, tels que InfoWars et The Gateway Pundit , connus pour publier des canulars et des théories du complot.[100] [101] [102]

Lors de son premier jour au pouvoir, Trump a faussement accusé les journalistes d’avoir sous-estimé la taille de la foule lors de son investiture et a qualifié les médias d’information de “parmi les êtres humains les plus malhonnêtes de la planète”. Les affirmations de Trump ont notamment été défendues par l’attaché de presse Sean Spicer, qui a affirmé que la foule d’inauguration avait été la plus importante de l’histoire, une affirmation démentie par des photographies. [103] La conseillère principale de Trump, Kellyanne Conway, a ensuite défendu Spicer lorsqu’elle a été interrogée sur le mensonge, affirmant qu’il s’agissait d’un ” fait alternatif “, et non d’un mensonge. [104]

L’administration a fréquemment cherché à punir et à bloquer l’accès aux journalistes qui ont publié des articles sur l’administration. [105] [106] [107] [108] Trump a fréquemment critiqué le média de droite Fox News pour ne pas l’avoir suffisamment soutenu, [109] menaçant de prêter son soutien à des alternatives à Fox News à droite. [110] Le 16 août 2018, le Sénat a adopté à l’unanimité une résolution affirmant que « la presse n’est pas l’ennemie du peuple ». [111]

La relation entre Trump, les médias d’information et les fausses nouvelles a été étudiée. Une étude a révélé qu’entre le 7 octobre et le 14 novembre 2016, alors qu’un Américain sur quatre visitait un faux site Web d’information , “les partisans de Trump visitaient les sites Web d’information les plus faux, qui étaient massivement pro-Trump” et “près de 6 visites sur 10 sur de faux sites Web”. les sites Web d’actualités provenaient des 10 % de personnes ayant les régimes d’information en ligne les plus conservateurs.” [112] [113] Brendan Nyhan , l’un des auteurs de l’étude, a déclaré dans une interview : “Les gens ont reçu beaucoup plus de fausses informations de Donald Trump que des faux sites Web d’informations.” [114]

Lors d’une conférence de presse conjointe, Trump s’est dit “très fier” d’entendre le président brésilien Jair Bolsonaro utiliser le terme “fake news”. [115]

Lors d’une conférence de presse conjointe, Trump s’est dit “très fier” d’entendre le président brésilien Jair Bolsonaro utiliser le terme “fake news”. [115]

En octobre 2018, Trump a félicité le représentant américain Greg Gianforte pour avoir agressé le journaliste politique Ben Jacobs en 2017. [116] Selon les analystes, l’incident a marqué la première fois que le président a « ouvertement et directement loué un acte violent contre un journaliste sur le sol américain. ” [117] Plus tard ce mois-là, alors que CNN et d’éminents démocrates étaient ciblés par des courriers piégés , Trump a d’abord condamné les tentatives d’attentat à la bombe, mais peu de temps après, il a accusé les “médias grand public que j’appelle Fake News” d’avoir causé “une très grande partie de la colère”. nous voyons aujourd’hui dans notre société.” [118]

Le ministère de la Justice de Trump a obtenu par ordonnance du tribunal les journaux téléphoniques ou les métadonnées des e-mails de 2017 des journalistes de CNN, du New York Times , du Washington Post , de BuzzFeed et de Politico dans le cadre d’enquêtes sur des fuites d’informations classifiées. [119]

Trump a continué à utiliser Twitter après la campagne présidentielle. Il a continué à tweeter personnellement depuis @realDonaldTrump, son compte personnel, tandis que son personnel tweetait en son nom en utilisant le compte officiel @POTUS. Son utilisation de Twitter n’était pas conventionnelle pour un président, ses tweets suscitant la controverse et devenant des nouvelles à part entière. [120] Certains chercheurs ont qualifié son mandat de “première véritable présidence de Twitter”. [121] L’administration Trump a décrit les tweets de Trump comme des “déclarations officielles du président des États-Unis”. [122] Un juge fédéral a statué en 2018 que le blocage par Trump d’autres utilisateurs de Twitter en raison d’opinions politiques opposées violait le premier amendement et qu’il devait les débloquer.[123] La décision a été confirmée en appel. [124] [125]

Activité Twitter de Donald Trump depuis son premier tweet en mai 2009 jusqu’en septembre 2017. Les retweets ne sont pas inclus.

Activité Twitter de Donald Trump depuis son premier tweet en mai 2009 jusqu’en septembre 2017. Les retweets ne sont pas inclus.

Ses tweets ont été signalés comme irréfléchis, impulsifs, vengeurs et intimidants , souvent diffusés tard dans la nuit ou aux petites heures du matin. [126] [127] [128] Ses tweets sur une interdiction musulmane ont été retournés avec succès contre son administration pour arrêter deux versions de restrictions de voyage de certains pays à majorité musulmane. [129] Il a utilisé Twitter pour menacer et intimider ses opposants politiques et alliés politiques potentiels nécessaires pour faire adopter des projets de loi. [130] De nombreux tweets semblent être basés sur des histoires que Trump a vues dans les médias, y compris des sites Web d’information d’extrême droite tels que Breitbart et des émissions de télévision telles que Fox & Friends . [131][132]

Trump a utilisé Twitter pour attaquer les juges fédéraux qui se sont prononcés contre lui dans des affaires judiciaires [133] et pour critiquer des responsables au sein de sa propre administration, y compris le secrétaire d’État de l’ époque Rex Tillerson , alors conseiller à la sécurité nationale H. R. McMaster , selon lesquels “il y avait d’énormes fuites, mensonge et corruption au plus haut niveau des départements du FBI, de la justice et de l’État ; [134] et que l’ enquête de l’avocat spécial est une ” CHASSE AUX SORCIÈRES ” le sous-procureur général Rod Rosenstein et , à divers moments, le procureur général Jeff Sessions. [134] Tillerson a finalement été licencié via un tweet de Trump. [135] Trump a également tweeté que son ministère de la Justice faisait partie de « l’État profond » américain ; [136] ! [137] En août 2018, Trump a utilisé Twitter pour écrire que le procureur général Jeff Sessions “devrait arrêter” immédiatement l’enquête de l’avocat spécial ; il l’a également qualifié de “truqué” et ses enquêteurs de partiaux. [138]

Sécurité Twitter @TwitterSafety Après un examen attentif des tweets récents du compte @realDonaldTrump et du contexte qui les entoure, nous avons définitivement suspendu le compte en raison du risque de nouvelles incitations à la violence.

8 janvier 2021 [139]

En février 2020, Trump a tweeté la critique de la peine proposée par les procureurs pour l’ancien assistant de Trump, Roger Stone . Quelques heures plus tard, le ministère de la Justice a remplacé la peine proposée par les procureurs par une proposition plus légère. Cela a donné l’apparence d’une ingérence présidentielle dans une affaire pénale et a provoqué une forte réaction négative. Les quatre procureurs d’origine se sont retirés de l’affaire; plus d’un millier d’anciens procureurs du DOJ ont signé une lettre condamnant l’action. [140] [141] Le 10 juillet, Trump a commué la peine de Stone quelques jours avant qu’il ne se présente en prison. [142]

En réponse aux manifestations de George Floyd de mi-2020 , dont certaines ont entraîné des pillages, [143] Trump a tweeté le 25 mai que « lorsque le pillage commence, le tournage commence ». Peu de temps après, Twitter a restreint le tweet pour violation de la politique de l’entreprise sur la promotion de la violence. [144] Le 28 mai, Trump a signé un décret visant à limiter les protections juridiques des entreprises de médias sociaux. [145]

Le 8 janvier 2021, Twitter a annoncé avoir suspendu définitivement le compte personnel de Trump « en raison du risque de nouvelles incitations à la violence » à la suite de l’ attaque du Capitole . [146] Trump a annoncé dans son dernier tweet avant la suspension qu’il n’assisterait pas à l’ investiture de Joe Biden . [147] D’autres plateformes de médias sociaux comme Facebook , Snapchat , YouTube et d’autres ont également suspendu les identifiants officiels de Donald Trump.[148] [149]

Affaires domestiques

Agriculture

En raison des tarifs commerciaux de Trump combinés à la baisse des prix des produits de base, les agriculteurs américains ont été confrontés à la pire crise depuis des décennies. [150] Trump a fourni aux agriculteurs 12 milliards de dollars en paiements directs en juillet 2018 pour atténuer les impacts négatifs de ses tarifs , augmentant les paiements de 14,5 milliards de dollars en mai 2019 après la fin des négociations commerciales avec la Chine sans accord. [151] La plupart des aides de l’administration sont allées aux plus grandes exploitations. [152] Politiquea rapporté en mai 2019 que certains économistes du Département de l’agriculture étaient punis pour avoir présenté des analyses montrant que les politiques commerciales et fiscales de Trump nuisaient aux agriculteurs, six économistes ayant plus de 50 ans d’expérience combinée au Service démissionnant le même jour. [153] Le budget de l’exercice 2020 de Trump proposait une réduction de 15 % du financement du ministère de l’Agriculture, qualifiant les subventions agricoles de « trop généreuses ». [150]

Protections des consommateurs

L’administration a annulé une règle du Bureau de protection financière des consommateurs (CFPB) qui avait permis aux consommateurs lésés de poursuivre plus facilement des recours collectifs contre les banques ; l’Associated Press a qualifié le renversement de victoire pour les banques de Wall Street. [154] Sous le mandat de Mick Mulvaney, le CFPB a réduit l’application des règles qui protégeaient les consommateurs contre les prêteurs sur salaire prédateurs . [155] [156] Trump a abandonné une proposition de règle de l’administration Obama selon laquelle les compagnies aériennes divulguent les frais de bagages. [157] Trump a réduit l’application des réglementations contre les compagnies aériennes ; les amendes imposées par l’administration en 2017 représentaient moins de la moitié de ce que l’administration Obama avait fait l’année précédente.[158]

Justice criminelle

Trump a signé une nouvelle législation contre le trafic sexuel le 16 avril 2018.

Trump a signé une nouvelle législation contre le trafic sexuel le 16 avril 2018.

Le New York Times a résumé « l’approche générale de l’administration Trump en matière d’application de la loi » comme « réprimant les crimes violents », « ne réglementant pas les services de police qui les combattent » et révisant « les programmes que l’administration Obama utilisait pour apaiser les tensions entre les communautés et la police”. [159] Trump a annulé une interdiction de fournir de l’équipement militaire fédéral aux services de police locaux [160] et a rétabli l’utilisation de la confiscation des biens civils . [161]L’administration a déclaré qu’elle n’enquêterait plus sur les services de police et ne publierait plus leurs lacunes dans les rapports, une politique précédemment adoptée sous l’administration Obama. Plus tard, Trump a faussement affirmé que l’administration Obama n’avait jamais tenté de réformer la police. [162] [163]

En décembre 2017, le DOJ, sous les ordres du premier procureur général de Trump, Jeff Sessions, a annulé les directives mises en place sous l’administration Obama visant à mettre en garde les tribunaux locaux contre l’imposition d’amendes et de frais excessifs aux accusés pauvres. [164]

Trump rend hommage aux policiers décédés le 15 mai 2017

Trump rend hommage aux policiers décédés le 15 mai 2017

Malgré la rhétorique pro-police de Trump, son plan budgétaire de 2019 proposait des réductions de près de cinquante pour cent du programme d’embauche COPS, qui fournit un financement aux organismes d’application de la loi des États et locaux pour aider à embaucher des agents de police communautaires. [165] Trump a semblé prôner la brutalité policière dans un discours prononcé en juillet 2017 devant des policiers, suscitant les critiques des forces de l’ordre. [166] En 2020, l’inspecteur général du DOJ a critiqué l’administration Trump pour avoir réduit la surveillance de la police et érodé la confiance du public dans les forces de l’ordre. [167]

En décembre 2018, Trump a signé le First Step Act , un projet de loi bipartite sur la réforme de la justice pénale qui visait à réhabiliter les prisonniers et à réduire la récidive, notamment en élargissant les programmes de formation professionnelle et de libération anticipée, et en abaissant les peines minimales obligatoires pour les délinquants toxicomanes non violents. [168] Le budget 2020 proposé par Trump a sous-financé la nouvelle loi ; la loi était censée recevoir 75 millions de dollars par an pendant cinq ans, mais le budget de Trump ne proposait que 14 millions de dollars. [169]

À partir de sa campagne et pendant sa présidence, Trump a appelé à une enquête approfondie sur les actes répréhensibles présumés d’Hillary Clinton. [170] [171] En novembre 2017, les sessions du procureur général ont nommé un procureur fédéral pour examiner un large éventail de questions, notamment la Fondation Clinton , la controverse Uranium One et la gestion par le FBI de son enquête sur les courriels d’Hillary Clinton. En janvier 2020, l’enquête aurait pris fin après qu’aucune preuve n’ait été trouvée pour justifier l’ouverture d’une enquête pénale. [172] Le rapport d’avril 2019 de l’avocat spécial Robert Mueller a documenté que Trump avait fait pression sur Sessions et le DOJ pour rouvrir l’enquête sur les courriels de Clinton.[173]

Le nombre de poursuites contre les trafiquants sexuels d’enfants a montré une tendance à la baisse sous l’administration Trump par rapport à l’administration Obama. [174] [175] Sous l’administration Trump, la SEC a accusé le plus petit nombre d’affaires de délit d’initié depuis l’administration Reagan. [176]

Grâces présidentielles et commutations

Au cours de sa présidence, Trump a gracié ou commué les peines de 237 personnes. [177] La plupart des personnes graciées avaient des liens personnels ou politiques avec Trump. [178] Un nombre important avait été reconnu coupable de fraude ou de corruption publique. [179] Trump a contourné le processus de clémence typique, ne prenant aucune mesure sur plus de dix mille demandes en attente, utilisant le pouvoir de grâce principalement sur “des personnalités publiques dont les cas ont résonné en lui compte tenu de ses propres griefs avec les enquêteurs”. [180]

Politique en matière de drogue

En mai 2017, contrairement à la politique du DOJ d’Obama visant à réduire les longues peines de prison pour les délits mineurs liés à la drogue et contrairement à un consensus bipartite croissant, l’administration a ordonné aux procureurs fédéraux de demander une peine maximale pour les délits liés à la drogue . [181] Dans une décision de janvier 2018 qui a créé une incertitude quant à la légalité de la marijuana à des fins récréatives et médicales, Sessions a annulé une politique fédérale qui avait interdit aux responsables de l’application des lois fédérales d’appliquer de manière agressive la loi fédérale sur le cannabis dans les États où la drogue est légale. [182] La décision de l’administration contredit la déclaration du candidat de l’époque, Trump, selon laquelle la légalisation de la marijuana devrait être “la décision des États”. [183]Le même mois, la VA a déclaré qu’elle ne ferait pas de recherche sur le cannabis comme traitement potentiel contre le SSPT et la douleur chronique ; les organisations d’anciens combattants avaient fait pression pour une telle étude. [184]

Peine capitale

Pendant le mandat de Trump (en 2020 et en janvier 2021), le gouvernement fédéral a exécuté treize personnes en 2020 et janvier 2021 ; les premières exécutions depuis 2002. [185] Au cours de cette période, Trump a supervisé plus d’exécutions fédérales que n’importe quel président au cours des 120 années précédentes. [185]

Secours aux sinistrés

Trump signe le projet de loi sur l’ouragan Harvey à Camp David , le 8 septembre 2017 Ouragans Harvey, Irma et Maria

Trump signe le projet de loi sur l’ouragan Harvey à Camp David , le 8 septembre 2017 Ouragans Harvey, Irma et Maria

Trois ouragans ont frappé les États-Unis en août et septembre 2017 : Harvey dans le sud-est du Texas, Irma sur la côte du golfe de Floride et Maria à Porto Rico. Trump a promulgué 15 milliards de dollars d’aide pour Harvey et Irma, puis 18,67 milliards de dollars pour les trois. [186] L’administration a été critiquée pour sa réponse tardive à la crise humanitaire à Porto Rico. [187] Les politiciens des deux partis avaient appelé à une aide immédiate pour Porto Rico et critiqué Trump pour s’être plutôt concentré sur une querelle avec la NFL. [188] Trump n’a fait aucun commentaire sur Porto Rico pendant plusieurs jours alors que la crise se déroulait. [189] Selon Le Washington Post, la Maison Blanche n’a ressenti aucun sentiment d’urgence jusqu’à ce que « des images de la destruction totale et du désespoir – et des critiques de la réponse de l’administration – aient commencé à apparaître à la télévision ». [190] Trump a rejeté la critique, affirmant que la distribution des fournitures nécessaires « se passait bien ». Le Washington Post a noté que “sur le terrain à Porto Rico, rien ne pourrait être plus éloigné de la vérité”. [190] Trump a également critiqué les responsables de Porto Rico. [191] Une analyse du BMJ a révélé que le gouvernement fédéral a réagi beaucoup plus rapidement et à plus grande échelle à l’ouragan au Texas et en Floride qu’à Porto Rico, malgré le fait que l’ouragan à Porto Rico était plus grave. [186]Une enquête de l’inspecteur général du HUD en 2021 a révélé que l’administration Trump avait érigé des obstacles bureaucratiques qui ont bloqué environ 20 milliards de dollars de secours aux ouragans pour Porto Rico. [192]

Au moment du départ de la FEMA de Porto Rico, un tiers des habitants de Porto Rico manquaient encore d’électricité et certains endroits manquaient d’eau courante. [193] Une étude du New England Journal of Medicine a estimé le nombre de décès liés à l’ouragan au cours de la période du 20 septembre au 31 décembre 2017 à environ 4 600 (intervalle de 793 à 8 498) [194] Le taux de mortalité officiel dû à Maria a rapporté par le Commonwealth de Porto Rico est de 2 975 ; le chiffre était basé sur une enquête indépendante de l’Université George Washington commandée par le gouverneur de Porto Rico. [195] Trump a faussement affirmé que le taux de mortalité officiel était erroné et a déclaré que les démocrates essayaient de le faire « paraître aussi mauvais que possible ». [196]

Incendies de forêt en Californie

Trump a imputé à tort les incendies de forêt destructeurs de 2018 en Californie , à la “mauvaise” et “mauvaise” “mauvaise” gestion des forêts par la Californie, affirmant qu’il n’y avait aucune autre raison à ces incendies de forêt. Les incendies en question n’étaient pas des “feux de forêt” ; la majeure partie de la forêt appartenait à des agences fédérales; et le changement climatique a en partie contribué aux incendies. [197]

En septembre 2020, les pires incendies de forêt de l’histoire de la Californie ont incité Trump à visiter l’État. Lors d’un briefing aux responsables de l’État, Trump a déclaré que l’aide fédérale était nécessaire et a de nouveau affirmé sans fondement que le manque de foresterie , et non le changement climatique, est la cause sous-jacente des incendies. [198]

Économie

| An | Chômage [ 199 ] |

PIB [200] | Croissance du PIB réel [201] | Données fiscales [202] [203] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reçus | Dépenses | Déficit | Dette | ||||

| fin | 31 décembre (année civile) | 30 septembre (année fiscale) [1] | |||||

| 2016* | 4,9 % | $18.695 | 1,7 % | $3.268 | $3.853 | – 0,585 $ | 14,2 $ |

| 2017 | 4,4 % | $19.480 | 2,3 % | $3.316 | $3.982 | – 0,665 $ | 14,7 $ |

| 2018 | 3,9 % | $20.527 | 2,9 % | $3.330 | $4.109 | – 0,779 $ | 15,8 $ |

| 2019 | 3,7 % | $21.373 | 2,3 % | $3.463 | $4.447 | – 0,984 $ | 16,8 $ |

| 2020 | 8,1 % | $20.894 | –3,4% | $3.421 | $6.550 | – 3,129 $ | 21,0 $ |

Les politiques économiques de Trump se sont concentrées sur la réduction des impôts, la déréglementation et le protectionnisme commercial. Trump s’est principalement tenu à ou a intensifié les positions de politique économique républicaines traditionnelles qui profitaient aux intérêts des entreprises ou aux riches, à l’exception de ses politiques protectionnistes commerciales. [204] Les dépenses déficitaires , combinées aux réductions d’impôts pour les riches, ont entraîné une forte augmentation de la dette nationale américaine . [205] [206] [207] [208]

L’une des premières actions de Trump a été de suspendre indéfiniment une réduction des taux de frais pour les hypothèques assurées par le gouvernement fédéral mise en œuvre par l’administration Obama, ce qui a permis aux personnes ayant des cotes de crédit inférieures d’environ 500 $ par an sur un prêt typique. [209] Dès son entrée en fonction, Trump a interrompu les négociations commerciales avec l’Union européenne sur le partenariat transatlantique de commerce et d’investissement , qui étaient en cours depuis 2013. [210]

L’administration a proposé des changements au programme d’assistance nutritionnelle supplémentaire (bons alimentaires), qui, s’ils étaient mis en œuvre, entraîneraient la perte de l’accès aux bons alimentaires par des millions de personnes et limiteraient le montant des prestations pour les bénéficiaires restants. [211]

Au cours de son mandat, Trump a cherché à plusieurs reprises à intervenir dans l’économie pour affecter des entreprises et des industries spécifiques. [212] Trump a cherché à obliger les opérateurs de réseaux électriques à acheter du charbon et de l’énergie nucléaire, et a demandé des tarifs sur les métaux pour protéger les producteurs nationaux de métaux. [212] Trump a également attaqué publiquement Boeing et Lockheed Martin , faisant chuter leurs actions. [213] Trump a critiqué à plusieurs reprises Amazon et a préconisé des mesures qui nuiraient à l’entreprise, comme mettre fin à un accord entre Amazon et le service postal des États-Unis (USPS) et augmenter les impôts sur Amazon. [214] [215]Trump a exprimé son opposition à la fusion entre Time Warner (la société mère de CNN) et AT&T . [216]

La campagne Trump s’est déroulée sur une politique de réduction du déficit commercial américain, en particulier avec la Chine. [217] Le déficit commercial global a augmenté pendant la présidence de Trump. [218] Le déficit des marchandises avec la Chine a atteint un niveau record pour la deuxième année consécutive en 2018. [219]

Une étude de 2021, qui a utilisé la méthode de contrôle synthétique , n’a trouvé aucune preuve que Trump ait eu un impact sur l’économie américaine pendant son mandat. [220] Une analyse menée par Bloomberg News à la fin de la deuxième année de mandat de Trump a révélé que son économie se classait sixième parmi les sept derniers présidents, sur la base de quatorze mesures d’activité économique et de performance financière. [221] Trump a décrit à plusieurs reprises et à tort l’économie pendant sa présidence comme la meilleure de l’histoire américaine. [222]

Trump et le PDG de Boeing , Dennis Muilenburg , lors de la cérémonie de déploiement du 787-10 Dreamliner

Trump et le PDG de Boeing , Dennis Muilenburg , lors de la cérémonie de déploiement du 787-10 Dreamliner

En février 2020, au milieu de la pandémie de COVID-19 , les États-Unis sont entrés en récession . [223] [224]

Imposition

En septembre 2017, Trump a proposé la refonte de la fiscalité fédérale la plus radicale depuis de nombreuses années. [225] Trump a signé la législation fiscale le 22 décembre 2017, après son adoption par le Congrès sur des votes de parti. [226] [227] [228] Le projet de loi fiscale a été la première grande législation signée par Trump. [229] Le projet de loi de 1 500 milliards de dollars a réduit le taux d’imposition fédéral des sociétés de 35 % à 21 %, [227] son point le plus bas depuis 1939. [228] Le projet de loi a également réduit le taux d’imposition des particuliers, réduisant le taux maximal de 39,6 % à 37 %. %, bien que ces réductions d’impôts individuelles expirent après 2025 ; [227] en conséquence, “d’ici 2027, chaque groupe de revenu gagnant moins de 75 000 $ verrait une augmentation nette de l’impôt”.[229] Le projet de loi a doublé l’ exonération de l’ impôt sur les successions (à 22 millions de dollars pour les couples mariés) ; et a permis aux propriétaires d’entreprises intermédiaires de déduire 20 % du revenu d’entreprise. [227] Le projet de loi a doublé la déduction forfaitaire tout en éliminant de nombreuses déductions détaillées , [229] y compris la déduction pour les impôts d’État et locaux. [227] Le projet de loi a également répété le mandat d’assurance maladie individuelle contenu dans la Loi sur les soins abordables . [229]

Selon le New York Times , le plan se traduirait par une “énorme aubaine” pour les très riches mais ne profiterait pas à ceux qui se situent dans le tiers inférieur de la répartition des revenus. [225] Le centre de politique fiscale non partisan a estimé que les 0,1 % et 1 % les plus riches bénéficieraient le plus du plan fiscal en termes de montants bruts et de pourcentage, gagnant respectivement 10,2 % et 8,5 % de revenus après impôts. [230] Les ménages de la classe moyenne gagneraient en moyenne 1,2 % de plus après impôt, mais 13,5 % des ménages de la classe moyenne verraient leur pression fiscale augmenter. [230] Le cinquième le plus pauvre des Américains gagnerait 0,5 % de plus. [230] Secrétaire au Trésor Steven Mnuchinont fait valoir que la réduction de l’impôt sur les sociétés profiterait le plus aux travailleurs, tandis que le comité mixte non partisan sur la fiscalité, le bureau du budget du Congrès et de nombreux économistes estimaient que les propriétaires du capital bénéficieraient beaucoup plus que les travailleurs. [231] Une estimation préliminaire du Comité pour un budget fédéral responsable a révélé que le plan fiscal ajouterait plus de 2 000 milliards de dollars au cours de la prochaine décennie à la dette fédérale, [232] tandis que le Tax Policy Center a constaté qu’il ajouterait 2 400 milliards de dollars à la dette fédérale. la dette. [230] Une analyse du Service de recherche du Congrès de 2019 a révélé que les réductions d’impôts avaient “un effet de croissance relativement faible (le cas échéant) la première année” sur l’économie. [233] Une analyse de 2019 par leLe Comité pour un budget fédéral responsable a conclu que les politiques de Trump ajouteront 4,1 billions de dollars à la dette nationale de 2017 à 2029. Environ 1,8 billion de dollars de dette devraient éventuellement résulter de la loi de 2017 sur les réductions d’impôts et l’emploi. [234]

Échange

Trump signe l’ accord États-Unis-Mexique-Canada (USMCA) aux côtés du président mexicain Enrique Peña Nieto et du premier ministre canadien Justin Trudeau à Buenos Aires , Argentine, le 30 novembre 2018

Trump signe l’ accord États-Unis-Mexique-Canada (USMCA) aux côtés du président mexicain Enrique Peña Nieto et du premier ministre canadien Justin Trudeau à Buenos Aires , Argentine, le 30 novembre 2018

En mars 2018, Trump a imposé des tarifs sur les panneaux solaires et les machines à laver de 30 à 50 %. [235] En mars 2018, il a imposé des droits de douane sur l’acier (25 %) et l’aluminium (10 %) de la plupart des pays, [236] [237] qui couvraient environ 4,1 % des importations américaines. [238] Le 1er juin 2018, cela a été étendu à l’ Union européenne , au Canada et au Mexique . [237] Dans des démarches distinctes, l’administration Trump a fixé et augmenté les droits de douane sur les marchandises importées de Chine , ce qui a conduit à une guerre commerciale . [239]Les tarifs ont provoqué la colère des partenaires commerciaux, qui ont mis en place des tarifs de rétorsion sur les produits américains, [240] et ont eu un effet négatif sur le revenu réel et le PIB. [241] Une analyse de la CNBC a révélé que Trump “a adopté des tarifs équivalant à l’une des plus fortes augmentations d’impôts depuis des décennies”, tandis que les analyses de la Tax Foundation et du Tax Policy Center ont révélé que les tarifs pourraient anéantir les avantages de la loi de 2017 sur les réductions d’impôts et l’emploi pour de nombreux ménages. [242] [243] Les deux pays sont parvenus à un accord de trêve de “phase un” en janvier 2020. La majeure partie des tarifs est restée en place jusqu’à ce que les pourparlers reprennent après les élections de 2020. Trump a fourni 28 milliards de dollars d’aide en espèces aux agriculteurs touchés par la guerre commerciale. [244] [245][246] Des études ont montré que les tarifs nuisaient également aux candidats républicains aux élections. [247] Une analyse publiée par le Wall Street Journal en octobre 2020 a révélé que la guerre commerciale n’a pas atteint l’objectif principal de relance de la fabrication américaine, ni n’a entraîné la relocalisation de la production en usine. [248]

Trois semaines après que le sénateur républicain Chuck Grassley , président de la commission des finances du Sénat , ait écrit un éditorial du Wall Street Journal d’avril 2019 intitulé “Trump’s Tariffs End or His Trade Deal Dies”, déclarant que “le Congrès n’approuvera pas l’ USMCA tant que les électeurs en paieront le prix “. pour les représailles mexicaines et canadiennes », Trump a levé les tarifs de l’acier et de l’aluminium sur le Mexique et le Canada. [249] Deux semaines plus tard, Trump a annoncé de manière inattendue qu’il imposerait un tarif de 5 % sur toutes les importations en provenance du Mexique le 10 juin, passant à 10 % le 1er juillet, et de 5 % supplémentaires chaque mois pendant trois mois, « jusqu’à ce que migrants illégaux qui passent par le Mexique et entrent dans notre pays, STOP”. [250]Grassley a qualifié cette décision de “détournement de l’autorité tarifaire présidentielle et contraire à l’intention du Congrès”. [251] Le même jour, l’administration Trump a officiellement lancé le processus visant à obtenir l’approbation du Congrès de l’USMCA. [252] Le principal conseiller commercial de Trump, le représentant américain au commerce, Robert Lighthizer , s’est opposé aux nouveaux tarifs mexicains, craignant qu’ils ne compromettent l’adoption de l’USMCA. [253] Le secrétaire au Trésor Steven Mnuchin et le conseiller principal de Trump Jared Kushner se sont également opposés à l’action. Grassley, dont le comité joue un rôle déterminant dans le passage de l’USMCA, n’a pas été informé à l’avance de l’annonce surprise de Trump. [254]Le 7 juin, Trump a annoncé que les tarifs seraient “suspendus indéfiniment” après que le Mexique a accepté de prendre des mesures, notamment en déployant sa garde nationale dans tout le pays et le long de sa frontière sud. [255] Le New York Times a rapporté le lendemain que le Mexique avait en fait accepté la plupart des actions des mois plus tôt. [256]

En tant que candidat à la présidence en 2016, Trump s’est engagé à se retirer du Partenariat transpacifique , un accord commercial avec onze pays du Pacifique que les États-Unis avaient signé plus tôt cette année-là. La Chine n’était pas partie à l’accord, qui visait à permettre aux États-Unis de guider les relations commerciales dans la région. Il a affirmé à tort que l’accord était défectueux car il contenait une “porte dérobée” qui permettrait à la Chine de conclure l’accord plus tard. Trump a annoncé le retrait américain de l’accord quelques jours après son entrée en fonction. Lors du retrait américain, les partenaires restants l’ont rebaptisé Accord global et progressiste de partenariat transpacifique. En septembre 2021, la Chine a officiellement demandé à adhérer à cet accord dans le but de remplacer les États-Unis en tant que plaque tournante ; Le Global Times , géré par l’État chinois, a déclaré que cette décision “consoliderait le leadership du pays dans le commerce mondial” et laisserait les États-Unis “de plus en plus isolés”. [257] [258]

Éducation

Trump et la secrétaire à l’éducation Betsy DeVos visitent l’école catholique Saint Andrew’s à Orlando, en Floride, le 3 mars 2017

Trump et la secrétaire à l’éducation Betsy DeVos visitent l’école catholique Saint Andrew’s à Orlando, en Floride, le 3 mars 2017

Trump a nommé Betsy DeVos au poste de secrétaire à l’Éducation. Sa nomination a été confirmée lors d’un vote à 50-50 au Sénat avec le vice-président Pence appelé à briser l’égalité (la première fois qu’un vice-président avait émis un vote décisif sur une nomination au Cabinet). [259] Les démocrates se sont opposés à DeVos comme étant sous-qualifiés, tandis que les républicains ont soutenu DeVos en raison de son fort soutien au choix de l’école . [259]

En 2017, Trump a révoqué une note de service de l’administration Obama qui prévoyait des protections pour les personnes en défaut de remboursement des prêts étudiants. [260] Le Département de l’éducation a annulé les accords avec le Bureau de protection financière des consommateurs (CFPB) pour contrôler la fraude aux prêts étudiants. [261] L’administration a abrogé un règlement limitant le financement fédéral aux collèges à but lucratif incapables de démontrer que les diplômés des collèges avaient un ratio d’endettement raisonnable après leur entrée sur le marché du travail. [262] Seth Frotman, l’ombudsman des prêts étudiants du CFPB, a démissionné, accusant l’administration Trump de saper le travail du CFPB sur la protection des étudiants emprunteurs. [263]DeVos a marginalisé une unité d’enquête au sein du ministère de l’Éducation qui, sous Obama, enquêtait sur les activités prédatrices des collèges à but lucratif. Une enquête ouverte sous Obama sur les pratiques de DeVry Education Group, qui gère des collèges à but lucratif, a été interrompue au début de 2017, et l’ancien doyen de DeVry a été nommé superviseur de l’unité d’enquête plus tard cet été-là. DeVry a payé une amende de 100 millions de dollars en 2016 pour avoir fraudé des étudiants. [264]

En 2017, DeVos a déclaré que les conseils de l’administration Obama sur la manière dont les campus traitent les agressions sexuelles “ont échoué à trop d’étudiants” et elle a annoncé qu’elle avait l’intention de remplacer l’approche actuelle “par un système viable, efficace et équitable”. [265] Par conséquent, l’administration a abandonné une directive de l’administration Obama sur la manière dont les écoles et les universités devraient lutter contre le harcèlement sexuel et la violence sexuelle. DeVos a critiqué les directives pour avoir porté atteinte aux droits des personnes accusées de harcèlement sexuel. [266]

Intégrité électorale

À la veille des élections de mi-mandat de 2018, Politico a qualifié les efforts de l’administration Trump pour lutter contre la propagande électorale de “sans gouvernail”. Dans le même temps, les agences de renseignement américaines ont mis en garde contre les “campagnes en cours” de la Russie, de la Chine et de l’Iran pour influencer les élections américaines. [267]

Énergie

Le “America First Energy Plan” de l’administration ne mentionnait pas les énergies renouvelables et se concentrait plutôt sur les combustibles fossiles. [268] L’administration a décrété des droits de douane de 30% sur les panneaux solaires importés. L’industrie américaine de l’énergie solaire est fortement dépendante des pièces étrangères (80 % des pièces sont fabriquées à l’étranger) ; en conséquence, les tarifs pourraient augmenter les coûts de l’énergie solaire, réduire l’innovation et réduire les emplois dans l’industrie – qui en 2017 employait près de quatre fois plus de travailleurs américains que l’industrie du charbon. [269] [270] L’administration a inversé les normes mises en place pour rendre les ampoules couramment utilisées plus économes en énergie. [271]

Trump a annulé une règle obligeant les entreprises pétrolières, gazières et minières à divulguer le montant qu’elles versaient aux gouvernements étrangers [272] et s’est retiré de l’ Initiative internationale pour la transparence des industries extractives (ITIE) qui exigeait la divulgation des paiements des entreprises pétrolières, gazières et minières aux gouvernements. [273]

En 2017, Trump a ordonné l’annulation d’une interdiction de l’ère Obama sur les nouvelles concessions pétrolières et gazières dans l’océan Arctique et les zones écologiquement sensibles de la côte nord de l’Atlantique , sur le plateau continental extérieur . [274] L’ordre de Trump a été interrompu par un tribunal fédéral, qui a statué en 2019 qu’il avait illégalement outrepassé son autorité. [274] Trump a également révoqué la Well Control Rule de 2016, un règlement de sécurité adopté après la marée noire de Deepwater Horizon ; cette action fait l’objet de contestations judiciaires de la part de groupes environnementaux. [275] [276] [277]

Rassemblement Trump d’avril 2017 à Harrisburg, Pennsylvanie

Rassemblement Trump d’avril 2017 à Harrisburg, Pennsylvanie

En janvier 2018, l’administration a choisi la Floride pour une exemption du plan de forage offshore de l’administration. Cette décision a suscité la controverse car elle est intervenue après que le gouverneur de Floride, Rick Scott , qui envisageait de se présenter au Sénat en 2018 , se soit plaint du plan. Cette décision a soulevé des questions éthiques sur l’apparition de “favoritisme transactionnel” parce que Trump possède une station balnéaire en Floride et en raison du statut de l’État en tant qu ‘”État tournant” crucial lors de l’élection présidentielle de 2020. [278] D’autres États ont demandé des exemptions similaires pour le forage en mer, [279] et des litiges ont suivi. [280] [281]

Malgré la rhétorique sur la relance de l’industrie du charbon, la capacité de production d’électricité au charbon a diminué plus rapidement pendant la présidence de Trump que pendant tout autre mandat présidentiel, chutant de 15 % avec la mise au ralenti de 145 unités au charbon dans 75 centrales électriques. On estime que 20 % de l’électricité devrait être produite par le charbon en 2020, contre 31 % en 2017. [282]

Environnement

En octobre 2020, l’ administration avait annulé 72 réglementations environnementales et était en train d’annuler 27 autres . contrairement à celle de toute administration précédente, car elle “s’est éloignée de l’intérêt public et a explicitement favorisé les intérêts des industries réglementées”. [284]

Les analyses des données d’application de l’EPA ont montré que l’administration Trump a intenté moins de poursuites contre les pollueurs, a demandé un total inférieur de sanctions civiles et a fait moins de demandes d’entreprises pour moderniser les installations afin de réduire la pollution que les administrations Obama et Bush. Selon le New York Times , “des documents internes confidentiels de l’EPA montrent que le ralentissement de l’application coïncide avec des changements de politique majeurs ordonnés par l’équipe de M. Pruitt après les appels des dirigeants de l’industrie pétrolière et gazière”. [285] En 2018, l’administration a renvoyé le plus petit nombre de cas de pollution à des poursuites pénales en 30 ans. [286] Deux ans après le début de la présidence de Trump, The New York Timesa écrit qu’il avait “déclenché un recul réglementaire, fait pression et encouragé par l’industrie, avec peu de parallèle au cours du dernier demi-siècle”. [287] En juin 2018, David Cutler et Francesca Dominici de l’Université de Harvard ont estimé prudemment que les modifications apportées par l’administration Trump aux règles environnementales pourraient entraîner plus de 80 000 décès supplémentaires aux États-Unis et des affections respiratoires généralisées. [288] En août 2018, la propre analyse de l’administration a montré que l’assouplissement des règles des centrales au charbon pourrait entraîner jusqu’à 1 400 décès prématurés et 15 000 nouveaux cas de problèmes respiratoires. [289]De 2016 à 2018, la pollution de l’air a augmenté de 5,5 %, inversant une tendance de sept ans où la pollution de l’air avait diminué de 25 %. [290]

Toutes les références au changement climatique ont été supprimées du site Web de la Maison Blanche, à la seule exception de la mention de l’intention de Trump d’éliminer les politiques de l’administration Obama en matière de changement climatique. [291] L’EPA a retiré de son site Web des informations sur le changement climatique, y compris des données climatiques détaillées. [292] En juin 2017, Trump a annoncé le retrait des États-Unis de l’ Accord de Paris , un accord de 2015 sur le changement climatique conclu par 200 nations pour réduire les émissions de gaz à effet de serre. [293] En décembre 2017, Trump – qui avait qualifié à plusieurs reprises le consensus scientifique sur le climat de « canular » avant de devenir président – a faussement laissé entendre que le temps froid signifiait que le changement climatique ne se produisait pas. [294]Par décret, Trump a annulé plusieurs politiques de l’administration Obama destinées à lutter contre le changement climatique, telles qu’un moratoire sur la location de charbon fédéral, le plan d’action présidentiel pour le climat et des conseils aux agences fédérales sur la prise en compte du changement climatique lors des examens d’action de la National Environmental Policy Act . Trump a également ordonné des révisions et éventuellement des modifications de plusieurs directives, telles que le Clean Power Plan (CPP), l’estimation du « coût social des émissions de carbone », les normes d’émission de dioxyde de carbone pour les nouvelles centrales au charbon, les normes d’ émissions de méthane du pétrole et du gaz naturel .l’extraction, ainsi que toute réglementation empêchant la production d’énergie domestique. [295] L’administration a annulé la réglementation obligeant le gouvernement fédéral à tenir compte du changement climatique et de l’élévation du niveau de la mer lors de la construction d’infrastructures. [296] L’EPA a dissous un groupe de 20 experts sur la pollution qui a conseillé l’EPA sur les seuils appropriés à fixer pour les normes de qualité de l’air. [297]

Portrait officiel de Scott Pruitt en tant qu’administrateur de l’EPA

Portrait officiel de Scott Pruitt en tant qu’administrateur de l’EPA

L’administration a cherché à plusieurs reprises à réduire le budget de l’EPA. [298] L’administration a invalidé la Stream Protection Rule , qui limitait le déversement d’eaux usées toxiques contenant des métaux, tels que l’arsenic et le mercure, dans les cours d’eau publics, [299] la réglementation sur les cendres de charbon (restes de déchets cancérigènes produits par les centrales au charbon), [300] et un décret exécutif de l’ère Obama sur la protection des océans, des côtes et des lacs promulgué en réponse à la marée noire de Deepwater Horizon . [301] L’administration a refusé d’agir sur les recommandations des scientifiques de l’EPA demandant une plus grande réglementation de la pollution particulaire. [302]

L’administration a annulé les principales protections de la Clean Water Act , réduisant la définition des « eaux des États-Unis » sous protection fédérale. [303] Des études menées par l’EPA de l’ère Obama suggèrent que jusqu’à deux tiers des cours d’eau douce de l’intérieur de la Californie perdraient leur protection en vertu du changement de règle. [304] L’EPA a cherché à abroger un règlement qui obligeait les sociétés pétrolières et gazières à limiter les émissions de méthane , un puissant gaz à effet de serre . [305] L’EPA a annulé les normes d’efficacité énergétique des automobiles introduites en 2012. [306] L’EPA a accordé une échappatoire permettant à un petit groupe d’entreprises de camionnage de contourner les règles d’émissions et de produirecamions planeurs qui émettent 40 à 55 fois plus de polluants atmosphériques que les autres camions neufs. [307] L’EPA a rejeté l’interdiction du pesticide toxique chlorpyrifos ; un tribunal fédéral a alors ordonné à l’EPA d’interdire le chlorpyrifos, car les recherches approfondies de l’EPA ont montré qu’il provoquait des effets néfastes sur la santé des enfants. [287] L’administration a réduit l’interdiction d’utiliser le solvant chlorure de méthylène , [308] et a levé une règle obligeant les grandes fermes à signaler la pollution émise par les déchets animaux. [309]

L’administration a suspendu le financement de plusieurs études de recherche environnementale, [310] [311] un programme de plusieurs millions de dollars qui distribuait des subventions pour la recherche sur les effets de l’exposition aux produits chimiques sur les enfants [312] [313] et la recherche de 10 millions de dollars par an ligne pour le système de surveillance du carbone de la NASA. [314] y compris une tentative infructueuse de tuer des aspects du programme de science climatique de la NASA . [314]

L’EPA a accéléré le processus d’approbation de nouveaux produits chimiques et rendu le processus d’évaluation de la sécurité de ces produits chimiques moins strict ; Les scientifiques de l’EPA ont exprimé leur inquiétude quant au fait que la capacité de l’agence à arrêter les produits chimiques dangereux était compromise. [315] [316] Des courriels internes ont montré que les aides de Pruitt ont empêché la publication d’une étude sur la santé montrant que certains produits chimiques toxiques mettent en danger les humains à des niveaux bien inférieurs à ceux que l’EPA avait précédemment qualifiés de sûrs. [317] Un de ces produits chimiques était présent en grande quantité autour de plusieurs bases militaires, y compris dans les eaux souterraines. [317]La non-divulgation de l’étude et le retard dans la diffusion publique des résultats ont peut-être empêché le gouvernement de moderniser l’infrastructure des bases et les personnes qui vivaient à proximité des bases pour éviter l’eau du robinet. [317]

L’administration a affaibli l’application de la loi sur les espèces en voie de disparition , facilitant le démarrage de projets d’exploitation minière, de forage et de construction dans des zones abritant des espèces en voie de disparition et menacées. [318] [319] L’administration a activement découragé les gouvernements locaux et les entreprises d’entreprendre des efforts de préservation. [319]

L’administration a fortement réduit la taille de deux monuments nationaux dans l’Utah d’environ deux millions d’acres, ce qui en fait la plus grande réduction des protections des terres publiques de l’histoire américaine. [320] Peu de temps après, le secrétaire à l’Intérieur Zinke a plaidé pour la réduction des effectifs de quatre monuments nationaux supplémentaires et la modification de la manière dont six monuments supplémentaires étaient gérés. [321] En 2019, l’administration a accéléré le processus d’examen environnemental des forages pétroliers et gaziers dans l’Arctique ; les experts ont déclaré que l’accélération rendait les examens moins complets et moins fiables. [322] Selon Politico, l’administration a accéléré le processus au cas où une administration démocrate serait élue en 2020, ce qui aurait interrompu de nouveaux baux pétroliers et gaziers dans l’Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. [322] L’administration a cherché à ouvrir plus de 180 000 acres de la forêt nationale de Tongass en Alaska, la plus grande du pays, à l’exploitation forestière. [323]

En avril 2018, Pruitt a annoncé un changement de politique interdisant aux régulateurs de l’EPA d’envisager la recherche scientifique à moins que les données brutes de la recherche ne soient rendues publiques. Cela limiterait l’utilisation par les régulateurs de l’EPA d’une grande partie de la recherche environnementale, étant donné que les participants à de nombreuses études de ce type fournissent des informations personnelles sur la santé qui restent confidentielles. [324] L’EPA a cité deux rapports bipartites et diverses études non partisanes sur l’utilisation de la science au sein du gouvernement pour défendre la décision. Cependant, les auteurs de ces rapports ont rejeté le fait que l’EPA avait suivi leurs instructions, l’un d’entre eux déclarant : “Ils n’adoptent aucune de nos recommandations, et ils vont dans une direction opposée, complètement différente. Ils n’adoptent aucune de nos recommandations.[325]

En juillet 2020, Trump a décidé d’affaiblir la loi sur la politique nationale de l’environnement en limitant l’examen public pour accélérer la délivrance des permis. [326]

Taille et réglementation du gouvernement