La ville de New York

New York , souvent appelée New York City ( NYC ) pour la distinguer de l’ état de New York , est la ville la plus peuplée des États-Unis. Avec une population en 2020 de 8 804 190 habitants répartis sur 300,46 miles carrés (778,2 km 2 ), New York est également la grande ville la plus densément peuplée des États-Unis. Située à la pointe sud de l’État de New York, la ville est le centre de l’ aire métropolitaine de New York , la plus grande aire métropolitaine du monde par aire urbaine . [9] Avec plus de 20,1 millions d’habitants dans sa zone statistique métropolitaineet 23,5 millions dans sa zone statistique combinée en 2020, New York est l’une des Mégapoles les plus peuplées du monde . La ville de New York a été décrite comme la capitale culturelle , financière et médiatique du monde et exerce une influence significative sur le commerce, le divertissement , la recherche, la technologie, l’ éducation , la politique , le tourisme , la restauration , l’art, la mode et le sport . C’est la ville la plus photographiée au monde. [10] Abritant le siège des Nations Unies , New York est un centre important pourdiplomatie internationale , [11] [12] et est parfois décrite comme la capitale du monde .

| New York | |

|---|---|

| Ville | |

De haut en bas, de gauche à droite : horizon du Lower Manhattan ; Parc central ; l’ Unisphère ; le pont de Brooklyn ; Terminal Grand Central ; la Statue de la Liberté ; le siège des Nations Unies ; et brownstones à Brooklyn De haut en bas, de gauche à droite : horizon du Lower Manhattan ; Parc central ; l’ Unisphère ; le pont de Brooklyn ; Terminal Grand Central ; la Statue de la Liberté ; le siège des Nations Unies ; et brownstones à Brooklyn |

|

Drapeau Drapeau  Joint Joint |

|

| Surnoms : La Grosse Pomme , La Ville qui ne dort jamais , Gotham et autres | |

Wikimédia | © OpenStreetMap Carte interactive de New York Wikimédia | © OpenStreetMap Carte interactive de New York |

|

| Coordonnées : 40°42′46′′N 74°00′22′′O / 40.71278°N 74.00611°W / 40.71278; -74.00611 [1]Coordinates: 40°42′46′′N 74°00′22′′W / 40.71278°N 74.00611°W / 40.71278; -74.00611 | |

| Pays | |

| État | |

| Région | Centre de l’Atlantique |

| Comtés constituants ( arrondissements ) | Bronx (Le Bronx) Kings (Brooklyn) New York (Manhattan) Queens (Queens) Richmond (Staten Island) |

| Colonies historiques | Nouvelle province néerlandaise de New York |

| Colonisé | 1624 (environ) |

| Consolidé | 1898 |

| Nommé pour | Jacques, duc d’York |

| Gouvernement | |

| • Taper | Maire-conseil fort |

| • Corps | Conseil municipal de New York |

| • Maire | Eric Adams ( D ) |

| Région [2] | |

| • Total | 472,43 milles carrés (1 223,59 km 2 ) |

| • Terre | 300,46 milles carrés (778,19 km 2 ) |

| • Eau | 171,97 milles carrés (445,40 km 2 ) |

| Élévation [3] | 33 pi (10 m) |

| Population ( 2020 ) [4] | |

| • Total | 8 804 190 |

| • Rang | 1er aux États-Unis 1er à New York |

| • Densité | 11 313,68 / km2 |

| • Métro [5] | 20 140 470 ( 1er ) |

| Démonyme(s) | New yorkais |

| Fuseau horaire | UTC−05:00 ( HNE ) |

| • Été ( DST ) | UTC−04:00 ( HAE ) |

| Codes ZIP | 100xx–104xx, 11004–05, 111xx–114xx, 116xx |

| Indicatif(s) régional(aux) | 212/646/332 , 718/347/929 , 917 |

| Code FIPS | 36-51000 |

| ID de fonctionnalité GNIS | 975772 |

| Aéroports internationaux | John F. Kennedy ( JFK ) LaGuardia ( LGA ) Newark Liberty ( EWR ) |

| Système de transport en commun rapide | Métro de New York , Chemin de fer de Staten Island , PATH |

| PIB (Ville, 2019) | 884 milliards de dollars [6] (1er) |

| BPF (Métro, 2020) | 1,67 billion de dollars [7] (1er) |

| Le plus grand arrondissement par superficie | Queens (109 milles carrés ou 280 kilomètres carrés) |

| Le plus grand arrondissement par la population | Brooklyn (2019 est. 2 559 903) [8] |

| Plus grand arrondissement par PIB (2019) | Manhattan (635,3 milliards de dollars) [6] |

| Site Internet | www .nyc .gov |

| Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO | |

| Nom officiel | Statue de la Liberté; L’architecture du XXe siècle de Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Taper | Culturel |

| Critère | je, ii, vi |

| Désigné | 1984, 2019 (8ème, 43ème sessions ) |

| Numéro de référence. | [4] ; [5] |

| État partie | États-Unis |

| Région | Europe et Amérique du Nord |

Située sur l’un des plus grands ports naturels du monde , la ville de New York est composée de cinq arrondissements , dont chacun est coextensif avec un comté respectif de l’État de New York . Les cinq arrondissements – Brooklyn (comté de Kings), Queens (comté de Queens), Manhattan (comté de New York), le Bronx (comté de Bronx) et Staten Island (comté de Richmond) – ont été créés lorsque les gouvernements locaux ont été regroupés en une seule entité municipale. en 1898. [13] La ville et sa zone métropolitaine constituent la première porte d’entrée pour l’ immigration légale aux États-Unis. Pas moins de 800 langues sont parlées à New York, [14] ce qui en fait la ville la plus linguistiquement diversifiée au monde. New York abrite plus de 3,2 millions d’habitants nés en dehors des États-Unis, la plus grande population née à l’étranger de toutes les villes du monde en 2016. [15] [16] En 2018 [update], la zone métropolitaine de New York est estimée à produire un produit métropolitain brut (GMP) de près de 1,8 billion de dollars, ce qui le place au premier rang aux États-Unis . Si la région métropolitaine de New York était un État souverain , elle aurait la huitième économie du monde. New York abrite le plus grand nombre de milliardairesde n’importe quelle ville du monde. [17]

La ville de New York trouve ses origines dans un poste de traite fondé sur la pointe sud de l’île de Manhattan par des colons néerlandais vers 1624. La colonie a été nommée New Amsterdam ( néerlandais : Nieuw Amsterdam ) en 1626 et a été affrété en tant que ville en 1653. La ville passa sous contrôle anglais en 1664 et fut rebaptisée New York après que le roi Charles II d’Angleterre eut accordé les terres à son frère, le duc d’York . [18] [19] La ville a été reconquise par les Néerlandais en juillet 1673 et a été rebaptisée Nouvelle Orange depuis un an et trois mois; la ville porte le nom de New York depuis novembre 1674. New York était la capitale des États-Unisde 1785 à 1790, [20] et a été la plus grande ville des États-Unis depuis 1790. La Statue de la Liberté a accueilli des millions d’immigrants lorsqu’ils sont venus aux États-Unis par bateau à la fin du 19e et au début du 20e siècle, et est un symbole des États-Unis et ses idéaux de liberté et de paix. [21] Au 21e siècle, New York a émergé comme un nœud mondial de créativité, d’entrepreneuriat, [22] et de durabilité environnementale, [23] [24] et comme un symbole de liberté et de diversité culturelle. [25] En 2019, New York a été élue la plus grande ville du monde selon une enquête menée auprès de plus de 30 000 personnes de 48 villes du monde, citant sa diversité culturelle. [26]

De nombreux quartiers et monuments de New York sont des points de repère majeurs, dont trois des dix attractions touristiques les plus visitées au monde en 2013. [27] Un record de 66,6 millions de touristes a visité New York en 2019. Times Square est le centre illuminé de Broadway . Quartier des théâtres , [28] l’un des carrefours piétonniers les plus fréquentés au monde, [27] [29] et un centre majeur de l’ industrie mondiale du divertissement . [30] De nombreux monuments, gratte -ciel et parcs de la ville sont connus dans le monde entier, tout comme le rythme rapide de la ville, donnant naissance au terme minute de New York .. L’ Empire State Building est devenu la norme mondiale de référence pour décrire la hauteur et la longueur des autres structures. [31] Le marché immobilier de Manhattan est l’un des plus chers au monde. [32] [33] Fournissant un service continu 24h/24 et 7j/7 et contribuant au surnom de La ville qui ne dort jamais , le métro de New York est le plus grand système de transport en commun rapide à opérateur unique au monde, avec 472 gares. La ville compte plus de 120 collèges et universités , dont l ‘ Université de Columbia , l’ Université de New York , l’ Université Rockefeller et laLe système de la City University of New York , qui est le plus grand système universitaire public urbain des États-Unis. Ancrée par Wall Street dans le quartier financier de Lower Manhattan, la ville de New York a été qualifiée à la fois de premier centre financier mondial et de ville la plus puissante financièrement du monde, et abrite les deux plus grandes bourses du monde en termes de capitalisation boursière totale , la Bourse de New York et Nasdaq . [34] [35]

Étymologie

En 1664, la ville est nommée en l’honneur du duc d’York , qui deviendra le roi Jacques II d’Angleterre . [36] Le frère aîné de James, le roi Charles II , nomma le duc propriétaire de l’ancien territoire de la Nouvelle-Hollande , y compris la ville de la Nouvelle-Amsterdam , lorsque l’Angleterre la saisit aux Hollandais . [37]

Histoire

Histoire ancienne

À l’ époque précoloniale , la région de l’actuelle ville de New York était habitée par des Amérindiens algonquiens , dont les Lenape . Leur patrie, connue sous le nom de Lenapehoking , comprenait Staten Island, Manhattan, le Bronx, la partie ouest de Long Island (y compris les zones qui deviendraient plus tard les arrondissements de Brooklyn et du Queens) et la vallée inférieure de l’Hudson . [38]

La première visite documentée dans le port de New York par un Européen a eu lieu en 1524 par l’Italien Giovanni da Verrazzano , un explorateur de Florence au service de la couronne française . [39] Il a revendiqué la région pour la France et l’a nommée Nouvelle Angoulême ( Nouvelle Angoulême ). [40] Une expédition espagnole , dirigée par le capitaine portugais Estêvão Gomes naviguant pour l’empereur Charles Quint , arriva dans le port de New York en janvier 1525 et cartographia l’embouchure de la rivière Hudson , qu’il nommaRío de San Antonio (fleuve Saint-Antoine). Le Padrón Real de 1527, la première carte scientifique à montrer la côte est de l’Amérique du Nord en continu, a été informé par l’expédition de Gomes et a étiqueté le nord-est des États-Unis comme Tierra de Esteban Gómez en son honneur. [41]

En 1609, l’explorateur anglais Henry Hudson a redécouvert le port de New York alors qu’il cherchait le passage du Nord-Ouest vers l’ Orient pour la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales . [42] Il a continué à remonter ce que les Néerlandais appelleraient la rivière du Nord (maintenant la rivière Hudson), nommée d’abord par Hudson comme la Maurice après Maurice, prince d’Orange . Le premier lieutenant d’Hudson a décrit le port comme “un très bon port pour tous les vents” et la rivière comme “large d’un mile” et “pleine de poissons”. [43] Hudson a navigué environ 150 milles (240 km) au nord, [44] devant le site de l’actuel État de New Yorkcapitale d’ Albany , dans la conviction qu’il pourrait s’agir d’un affluent océanique avant que la rivière ne devienne trop peu profonde pour continuer. [43] Il a fait une exploration de dix jours de la région et a revendiqué la région pour la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes orientales. En 1614, la zone située entre Cape Cod et la baie du Delaware fut revendiquée par les Pays-Bas et appelée Nieuw-Nederland ( New Netherland ).

Le premier habitant non amérindien de ce qui allait devenir la ville de New York était Juan Rodriguez ( translittéré en néerlandais sous le nom de Jan Rodrigues ), un marchand de Saint-Domingue . Né à Saint-Domingue d’ origine portugaise et africaine , il arriva à Manhattan pendant l’hiver 1613–14, piégeant pour les peaux et faisant du commerce avec la population locale en tant que représentant des Néerlandais. Broadway , de la 159e rue à la 218e rue dans l’Upper Manhattan , est nommé Juan Rodriguez Way en son honneur. [45] [46]

Règle néerlandaise

New Amsterdam , centrée dans l’éventuel Lower Manhattan , en 1664, l’année où l’Angleterre en prit le contrôle et la renomma “New York”.

New Amsterdam , centrée dans l’éventuel Lower Manhattan , en 1664, l’année où l’Angleterre en prit le contrôle et la renomma “New York”.

Une présence européenne permanente près du port de New York a commencé en 1624 – faisant de New York la 12e plus ancienne colonie européenne occupée en permanence dans la partie continentale des États-Unis [47] – avec la fondation d’une colonie hollandaise de traite des fourrures sur Governors Island . En 1625, la construction d’une citadelle et du Fort Amsterdam , plus tard appelé Nieuw Amsterdam (New Amsterdam), sur l’actuelle île de Manhattan , a commencé . [48] [49] La colonie de New Amsterdam était centrée sur ce qui serait finalement connu sous le nom de Lower Manhattan. Il s’étendait de la pointe sud de Manhattan à l’actuelle Wall Street , où une palissade en bois de 12 pieds a été construite en 1653 pour se protéger contre les raids amérindiens et britanniques. [50] En 1626, le directeur général colonial néerlandais Peter Minuit , agissant comme chargé par la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales , acheta l’île de Manhattan aux Canarsie , une petite bande de Lenape, [51] pour “la valeur de 60 florins ” [52] (environ 900 $ en 2018). [53] Une légende réfutée prétend que Manhattan a été acheté pour 24 $ de perles de verre. [54] [55]

Suite à l’achat, New Amsterdam a grandi lentement. [19] Pour attirer les colons, les Néerlandais ont institué le système des patrons en 1628, selon lequel les riches Hollandais ( patrons ou patrons) qui ont amené 50 colons en Nouvelle-Hollande se verraient attribuer des étendues de terre, ainsi que l’autonomie politique locale et le droit de participer à la lucrative traite des fourrures. Ce programme eut peu de succès. [56]

Depuis 1621, la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales fonctionnait en tant que monopole en Nouvelle-Hollande, sur autorisation accordée par les États généraux néerlandais . En 1639-1640, dans un effort pour soutenir la croissance économique, la Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales a renoncé à son monopole sur le commerce des fourrures, ce qui a entraîné une croissance de la production et du commerce de nourriture, de bois, de tabac et d’esclaves (en particulier avec les Antilles néerlandaises ). ). [19] [57]

En 1647, Peter Stuyvesant a commencé son mandat en tant que dernier directeur général de New Netherland. Au cours de son mandat, la population de New Netherland est passée de 2 000 à 8 000. [58] [59] Stuyvesant a été crédité d’avoir amélioré la loi et l’ordre dans la colonie; cependant, il a également acquis une réputation de chef despotique. Il a institué des réglementations sur les ventes d’alcool, a tenté d’exercer un contrôle sur l’ Église réformée néerlandaise et a empêché d’autres groupes religieux (y compris les quakers , les juifs et les luthériens ) d’établir des lieux de culte. [60]La Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes occidentales tentera finalement d’apaiser les tensions entre Stuyvesant et les habitants de New Amsterdam. [61]

règle anglaise

Fort George et la ville de New York v. 1731. Des navires de ligne de la Royal Navy gardent ce qui allait devenir le port de New York .

Fort George et la ville de New York v. 1731. Des navires de ligne de la Royal Navy gardent ce qui allait devenir le port de New York .

En 1664, incapable d’invoquer une résistance significative, Stuyvesant rendit la Nouvelle-Amsterdam aux troupes anglaises, dirigées par le colonel Richard Nicolls , sans effusion de sang. [60] [61] Les termes de la reddition permettaient aux résidents néerlandais de rester dans la colonie et permettaient la liberté religieuse. [62] En 1667, lors des négociations menant au traité de Breda après la seconde guerre anglo-néerlandaise , les Néerlandais décidèrent de conserver la colonie de plantation naissante de l’actuel Suriname (sur la côte nord de l’Amérique du Sud) qu’ils avaient acquise aux Anglais. ; et en échange, les Anglais gardaient la Nouvelle-Amsterdam . La colonie naissante a été rapidement rebaptisée “New York” après laDuc d’York (futurs rois Jacques II et VII), qui finira par être déposé lors de la Glorieuse Révolution . [63] Après la fondation, le duc a donné une partie de la colonie aux propriétaires George Carteret et John Berkeley . Fort Orange , à 150 miles (240 km) au nord sur la rivière Hudson , a été rebaptisé Albany après le titre écossais de James. [64] Le transfert est confirmé en 1667 par le traité de Breda , qui conclut la seconde guerre anglo-néerlandaise . [65]

Le 24 août 1673, pendant la troisième guerre anglo-néerlandaise , le capitaine hollandais Anthony Colve s’empare de la colonie de New York aux Anglais à la demande de Cornelis Evertsen le Jeune et la rebaptise « New Orange » d’après Guillaume III , le prince d’Orange . . [66] Les Néerlandais rendraient bientôt l’île à l’Angleterre en vertu du traité de Westminster de novembre 1674. [67] [68]

Plusieurs guerres intertribales parmi les Amérindiens et certaines épidémies provoquées par le contact avec les Européens ont causé des pertes de population importantes pour les Lenape entre les années 1660 et 1670. [69] En 1700, la population de Lenape avait diminué à 200. [70] New York a connu plusieurs épidémies de fièvre jaune au 18ème siècle, perdant dix pour cent de sa population à cause de la maladie en 1702 seulement. [71] [72]

Province de New York

L’université de Columbia a été fondée par charte royale en 1754 sous le nom de King’s College .

L’université de Columbia a été fondée par charte royale en 1754 sous le nom de King’s College .

New York a pris de l’importance en tant que port de commerce tout en faisant partie de la colonie de New York au début des années 1700. [73] Il est également devenu un centre d’ esclavage , avec 42 % des ménages détenant des esclaves en 1730, le pourcentage le plus élevé en dehors de Charleston , en Caroline du Sud . [74] La plupart des esclavagistes détenaient quelques ou plusieurs esclaves domestiques, mais d’autres les embauchaient pour travailler au travail. L’esclavage est devenu intégralement lié à l’économie de New York grâce au travail des esclaves dans tout le port et aux industries bancaires et maritimes faisant du commerce avec le sud des États-Unis . Découverte du cimetière africaindans les années 1990, lors de la construction d’un nouveau palais de justice fédéral près de Foley Square , a révélé que des dizaines de milliers d’Africains avaient été enterrés dans la région à l’époque coloniale. [75]

Le procès et l’acquittement en 1735 à Manhattan de John Peter Zenger , qui avait été accusé de diffamation séditieuse après avoir critiqué le gouverneur colonial William Cosby , a contribué à établir la liberté de la presse en Amérique du Nord. [76] En 1754, l’Université de Columbia a été fondée sous charte par le roi George II en tant que King’s College dans le Lower Manhattan. [77]

la révolution américaine

Le Stamp Act Congress s’est réuni à New York en octobre 1765, alors que les Sons of Liberty , organisés dans la ville, se sont affrontés au cours des dix années suivantes avec les troupes britanniques stationnées là-bas. [78] La bataille de Long Island , la plus grande bataille de la guerre d’indépendance américaine , a eu lieu en août 1776 dans le quartier moderne de Brooklyn. [79] Après la bataille, au cours de laquelle les Américains ont été vaincus, les Britanniques ont fait de la ville leur base militaire et politique d’opérations en Amérique du Nord. La ville était un refuge pour les loyalistesréfugiés et esclaves en fuite qui ont rejoint les lignes britanniques pour la liberté nouvellement promise par la Couronne pour tous les combattants. Pas moins de 10 000 esclaves en fuite se sont entassés dans la ville pendant l’occupation britannique. Lorsque les forces britanniques ont évacué à la fin de la guerre en 1783, elles ont transporté 3 000 affranchis pour les réinstaller en Nouvelle-Écosse . [80] Ils ont réinstallé d’autres affranchis en Angleterre et dans les Caraïbes .

La bataille de Long Island , la plus grande bataille de la Révolution américaine , a eu lieu à Brooklyn en 1776.

La bataille de Long Island , la plus grande bataille de la Révolution américaine , a eu lieu à Brooklyn en 1776.

La seule tentative de solution pacifique à la guerre eut lieu à la Conference House de Staten Island entre des délégués américains, dont Benjamin Franklin , et le général britannique Lord Howe , le 11 septembre 1776. Peu de temps après le début de l’occupation britannique, le grand incendie de New York s’est produite, une grande conflagration sur le West Side de Lower Manhattan, qui a détruit environ un quart des bâtiments de la ville, y compris l’église de la Trinité . [81]

En 1785, l’assemblée du Congrès de la Confédération fit de New York la capitale nationale peu après la guerre. New York était la dernière capitale des États-Unis en vertu des articles de la Confédération et la première capitale en vertu de la Constitution des États-Unis . La ville de New York, en tant que capitale des États-Unis, a accueilli plusieurs événements d’envergure nationale en 1789 : le premier président des États-Unis, George Washington , a été inauguré ; le premier Congrès des États-Unis et la Cour suprême des États-Unis se sont chacun réunis pour la première fois; et la Déclaration des droits des États-Unis a été rédigée, le tout au Federal Hall de Wall Street.[82] D’ici à 1790, New York avait surpassé Philadelphie pour devenir la plus grande ville aux États-Unis, mais vers la fin de cette année, conformément à l’ acte de Résidence , le capital national a été déplacé à Philadelphie. [83] [84]

XIXe siècle

Broadway suit le sentier amérindien Wickquasgeck à travers Manhattan. [85]

Broadway suit le sentier amérindien Wickquasgeck à travers Manhattan. [85]

Au cours du XIXe siècle, la population de New York est passée de 60 000 à 3,43 millions. [86] En vertu de l’acte d’ abolition de l’État de New York de 1799, les enfants de mères esclaves devaient finalement être libérés mais être tenus en servitude sous contrat jusqu’à la fin de la vingtaine. [87] [88] Avec les esclaves libérés par leurs maîtres après la guerre d’indépendance et les esclaves en fuite, une importante population noire libre s’est progressivement développée à Manhattan. Sous la direction de fondateurs américains aussi influents qu’Alexander Hamilton et John Jay , la New York Manumission Society a travaillé pour l’abolition et a établi laAfrican Free School pour éduquer les enfants noirs. [89] Ce n’est qu’en 1827 que l’esclavage a été complètement aboli dans l’État, et les Noirs libres ont ensuite lutté contre la discrimination. L’activisme abolitionniste interracial de New York s’est poursuivi; parmi ses dirigeants se trouvaient des diplômés de l’école libre africaine. La population de la ville de New York est passée de 123 706 en 1820 à 312 710 en 1840, dont 16 000 étaient noirs. [90] [91]

Au XIXe siècle, la ville se transforme à la fois par un développement commercial et résidentiel lié à son statut de centre commercial national et international , ainsi que par l’immigration européenne, respectivement. [92] La ville a adopté le plan des commissaires de 1811 , qui a élargi la grille des rues de la ville pour englober presque tout Manhattan. L’achèvement en 1825 du canal Érié à travers le centre de New York reliait le port de l’Atlantique aux marchés agricoles et aux marchandises de l’intérieur de l’Amérique du Nord via la rivière Hudson et les Grands Lacs . [93] La politique locale est devenue dominée parTammany Hall , une machine politique soutenue par des immigrants irlandais et allemands . [94]

Les 5 arrondissements actuels du Grand New York tels qu’ils apparaissaient en 1814. Le Bronx était dans le comté de Westchester, le comté de Queens comprenait le comté moderne de Nassau, le comté de Kings avait 6 villes, dont l’une était Brooklyn, New York City est représentée par des hachures dans le sud de New York Comté sur l’île de Manhattan et comté de Richmond sur Staten Island.

Les 5 arrondissements actuels du Grand New York tels qu’ils apparaissaient en 1814. Le Bronx était dans le comté de Westchester, le comté de Queens comprenait le comté moderne de Nassau, le comté de Kings avait 6 villes, dont l’une était Brooklyn, New York City est représentée par des hachures dans le sud de New York Comté sur l’île de Manhattan et comté de Richmond sur Staten Island.

Plusieurs personnalités littéraires américaines de premier plan ont vécu à New York dans les années 1830 et 1840, notamment William Cullen Bryant , Washington Irving , Herman Melville , Rufus Wilmot Griswold , John Keese , Nathaniel Parker Willis et Edgar Allan Poe . Des membres soucieux du public de l’élite commerciale contemporaine ont fait pression pour la création de Central Park , qui est devenu en 1857 le premier parc paysager d’une ville américaine.

La grande famine irlandaise a entraîné un afflux important d’immigrants irlandais; plus de 200 000 vivaient à New York en 1860, soit plus d’un quart de la population de la ville. [95] Il y avait aussi une importante immigration en provenance des provinces allemandes, où les révolutions avaient perturbé les sociétés, et les Allemands représentaient encore 25 % de la population de New York en 1860. [96]

Les candidats du Parti démocrate ont été systématiquement élus au bureau local, renforçant les liens de la ville avec le Sud et son parti dominant. En 1861, le maire Fernando Wood a appelé les échevins à déclarer l’indépendance d’Albany et des États-Unis après la sécession du Sud, mais sa proposition n’a pas été suivie d’effet. [89] La colère contre les nouvelles lois sur la conscription militaire pendant la guerre civile américaine (1861-1865), qui ont épargné les hommes plus riches qui pouvaient se permettre de payer des frais de commutation de 300 $ (équivalent à 6 602 $ en 2021) pour embaucher un remplaçant, [97] a conduit à les Draft Riots de 1863 , dont les participants les plus visibles étaient la classe ouvrière ethnique irlandaise. [89]

Les émeutes du projet se sont détériorées en attaques contre l’élite de New York, suivies d’attaques contre les New-Yorkais noirs et leurs biens après une concurrence féroce pendant une décennie entre les immigrants irlandais et les Noirs pour le travail. Les émeutiers ont incendié le Coloured Orphan Asylum, et plus de 200 enfants ont échappé au danger grâce aux efforts du département de police de New York , qui était principalement composé d’immigrants irlandais. [96] Au moins 120 personnes ont été tuées. [98] Onze hommes noirs ont été lynchés pendant cinq jours et les émeutes ont forcé des centaines de Noirs à fuir la ville pour Williamsburg , Brooklyn et le New Jersey. La population noire de Manhattan est tombée en dessous de 10 000 en 1865, ce qu’elle avait été pour la dernière fois en 1820. La classe ouvrière blanche avait établi sa domination.[96] [98] La violence des débardeurs contre les hommes noirs était particulièrement féroce dans la zone des quais. [96] Ce fut l’un des pires incidents de troubles civils de l’histoire américaine. [99]

Histoire moderne

Un ouvrier du bâtiment au sommet de l’ Empire State Building tel qu’il était en construction en 1930. Le Chrysler Building est derrière lui.

Un ouvrier du bâtiment au sommet de l’ Empire State Building tel qu’il était en construction en 1930. Le Chrysler Building est derrière lui.

En 1898, la ville moderne de New York a été formée avec la consolidation de Brooklyn (jusque-là une ville distincte), le comté de New York (qui comprenait alors des parties du Bronx), le comté de Richmond et la partie ouest de la Comté de Queens. [100] L’ouverture du métro en 1904, d’abord construit en tant que systèmes privés séparés, a aidé à lier la nouvelle ville ensemble. [101] Tout au long de la première moitié du 20ème siècle, la ville est devenue un centre mondial pour l’industrie, le commerce et la communication. [102]

En 1904, le vapeur General Slocum prend feu dans l’ East River , tuant 1 021 personnes à bord. [103] En 1911, l’ incendie de l’ usine Triangle Shirtwaist , la pire catastrophe industrielle de la ville, a coûté la vie à 146 ouvriers du vêtement et a stimulé la croissance de l’ Union internationale des ouvriers du vêtement pour femmes et des améliorations majeures des normes de sécurité des usines. [104]

La population non blanche de New York était de 36 620 en 1890. [105] New York était une destination de choix au début du XXe siècle pour les Afro-Américains pendant la grande migration du sud des États-Unis, et en 1916, New York était devenue le foyer de la plus grande diaspora africaine urbaine en Amérique du Nord. [106] La Renaissance de Harlem de la vie littéraire et culturelle s’est épanouie pendant l’ère d’ Interdiction . [107] Le boom économique plus large a généré la construction de gratte-ciel rivalisant de hauteur et créant une ligne d’ horizon identifiable .

La Petite Italie de Manhattan , Lower East Side , vers 1900

La Petite Italie de Manhattan , Lower East Side , vers 1900

New York est devenue la zone urbanisée la plus peuplée du monde au début des années 1920, dépassant Londres . La zone métropolitaine a dépassé la barre des 10 millions d’habitants au début des années 1930, devenant la première mégapole de l’histoire de l’humanité. [108] Les années difficiles de la Grande Dépression ont vu l’élection du réformateur Fiorello La Guardia comme maire et la chute de Tammany Hall après quatre-vingts ans de domination politique. [109]

Les anciens combattants de retour de la Seconde Guerre mondiale ont créé un boom économique d’après-guerre et le développement de vastes lotissements dans l’est du Queens et du comté de Nassau, ainsi que dans des zones suburbaines similaires du New Jersey. New York est sortie indemne de la guerre en tant que première ville du monde, avec Wall Street en tête de la place de l’Amérique en tant que puissance économique dominante du monde. Le siège des Nations Unies a été achevé en 1952, renforçant l’influence géopolitique mondiale de New York , et la montée de l’expressionnisme abstrait dans la ville a précipité le déplacement de New York de Paris en tant que centre du monde de l’art. [110]

Le Stonewall Inn à Greenwich Village , un monument historique national et un monument national des États-Unis , comme site des émeutes de Stonewall de juin 1969 et berceau du mouvement moderne des droits des homosexuels . [111] [112] [113]

Le Stonewall Inn à Greenwich Village , un monument historique national et un monument national des États-Unis , comme site des émeutes de Stonewall de juin 1969 et berceau du mouvement moderne des droits des homosexuels . [111] [112] [113]

Les émeutes de Stonewall étaient une série de manifestations spontanées et violentes de membres de la communauté gay contre une descente de police qui a eu lieu aux petites heures du matin du 28 juin 1969 au Stonewall Inn dans le quartier de Greenwich Village dans le Lower Manhattan. [114] Ils sont largement considérés comme constituant l’événement le plus important menant au mouvement de libération gay [111] [115] [116] [117] et à la lutte moderne pour les droits LGBT . [118] [119] Wayne R. Dynes , auteur duEncyclopedia of Homosexuality , a écrit que les drag queens étaient les seules «personnes transgenres autour» lors des émeutes de Stonewall de juin 1969 . La communauté transgenre de New York a joué un rôle important dans la lutte pour l’égalité des LGBT pendant la période des émeutes de Stonewall et par la suite. [120]

Dans les années 1970, les pertes d’emplois dues à la restructuration industrielle ont fait souffrir la ville de New York de problèmes économiques et d’un taux de criminalité en hausse. [121] Alors qu’une résurgence du secteur financier a considérablement amélioré la santé économique de la ville dans les années 1980, le taux de criminalité de New York a continué d’augmenter tout au long de cette décennie et au début des années 1990. [122] Au milieu des années 1990, les taux de criminalité ont commencé à chuter de façon spectaculaire en raison des stratégies policières révisées, de l’amélioration des opportunités économiques, de la gentrification et des nouveaux résidents, à la fois des greffes américaines et des nouveaux immigrants d’Asie et d’Amérique latine. De nouveaux secteurs importants, tels que Silicon Alley , ont émergé dans l’économie de la ville. [123]La population de New York a atteint des sommets sans précédent lors du recensement de 2000 , puis à nouveau lors du recensement de 2010.

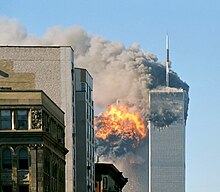

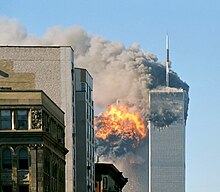

Le vol 175 de United Airlines frappe la tour sud du World Trade Center le 11 septembre 2001 .

Le vol 175 de United Airlines frappe la tour sud du World Trade Center le 11 septembre 2001 .

La ville de New York a subi l’essentiel des dommages économiques et la plus grande perte de vies humaines à la suite des attentats du 11 septembre 2001 . [124] Deux des quatre avions de ligne détournés ce jour-là ont été projetés dans les tours jumelles du World Trade Center, détruisant les tours et tuant 2 192 civils, 343 pompiers et 71 agents des forces de l’ordre. La tour nord est devenue le plus haut bâtiment jamais détruit à ce moment-là ou par la suite. [125]

La zone a été reconstruite avec un nouveau One World Trade Center , un mémorial et un musée du 11 septembre , et d’autres nouveaux bâtiments et infrastructures. [126] La station PATH du World Trade Center , qui avait ouvert le 19 juillet 1909, sous le nom de Hudson Terminal, a également été détruite lors des attaques. Une gare temporaire a été construite et ouverte le 23 novembre 2003. Une gare ferroviaire permanente de 800 000 pieds carrés (74 000 m 2 ) conçue par Santiago Calatrava , le World Trade Center Transportation Hub , le troisième plus grand hub de la ville, a été achevée en 2016 [127] Le nouveau One World Trade Center est le plus haut gratte-ciel de l’hémisphère occidental [128]et le sixième bâtiment le plus haut du monde par sa hauteur de pinacle , avec sa flèche atteignant une symbolique de 1 776 pieds (541,3 m) en référence à l’année de l’indépendance des États-Unis . [129] [130] [131] [132]

Les manifestations Occupy Wall Street à Zuccotti Park dans le quartier financier de Lower Manhattan ont commencé le 17 septembre 2011, attirant l’attention mondiale et popularisant le mouvement Occupy contre les inégalités sociales et économiques dans le monde. [133]

En mars 2020, le premier cas de COVID-19 dans la ville a été confirmé à Manhattan. [134] La ville a rapidement remplacé Wuhan, en Chine, pour devenir l’épicentre mondial de la pandémie au cours de la première phase, avant que l’infection ne se généralise dans le monde et dans le reste du pays. En mars 2021, la ville de New York avait enregistré plus de 30 000 décès dus à des complications liées au COVID-19.

Géographie

Le cœur de la zone métropolitaine de New York , avec l’île de Manhattan en son centre.

Le cœur de la zone métropolitaine de New York , avec l’île de Manhattan en son centre.

Pendant la glaciation du Wisconsin , il y a 75 000 à 11 000 ans, la région de New York était située au bord d’une grande calotte glaciaire de plus de 2 000 pieds (610 m) de profondeur. [135] Le mouvement vers l’avant érosif de la glace (et sa retraite subséquente) a contribué à la séparation de ce qui est maintenant Long Island et Staten Island . Cette action a également laissé le socle rocheux à une profondeur relativement faible, fournissant une base solide à la plupart des gratte-ciel de Manhattan. [136]

La ville de New York est située dans le nord-est des États-Unis , dans le sud-est de l’État de New York, à peu près à mi-chemin entre Washington, DC et Boston . L’emplacement à l’embouchure de la rivière Hudson , qui alimente un port naturellement abrité, puis dans l’océan Atlantique, a aidé la ville à prendre de l’importance en tant que port de commerce. La majeure partie de New York est construite sur les trois îles de Long Island , Manhattan et Staten Island.

La rivière Hudson coule à travers la vallée de l’ Hudson dans la baie de New York . Entre New York et Troy, New York , la rivière est un estuaire . [137] Le fleuve Hudson sépare la ville de l’État américain du New Jersey . L’ East River – un détroit de marée – coule de Long Island Sound et sépare le Bronx et Manhattan de Long Island. La rivière Harlem , un autre détroit de marée entre les rivières East et Hudson, sépare la majeure partie de Manhattan du Bronx. La rivière Bronx , qui traverse le Bronx et le comté de Westchester, est la seule rivière entièrement d’eau douce de la ville. [138]

Le terrain de la ville a été considérablement modifié par l’intervention humaine, avec une poldérisation considérable le long des fronts de mer depuis l’époque coloniale néerlandaise; la remise en état est la plus importante dans le Lower Manhattan , avec des développements tels que Battery Park City dans les années 1970 et 1980. [139] Une partie du relief naturel de la topographie a été égalisée, en particulier à Manhattan. [140]

La superficie totale de la ville est de 468,484 milles carrés (1 213,37 km 2 ); 302,643 milles carrés (783,84 km 2 ) de la ville sont terrestres et 165,841 milles carrés (429,53 km 2 ) sont de l’eau. [141] [142] Le point culminant de la ville est Todt Hill sur Staten Island, qui, à 409,8 pieds (124,9 m) au-dessus du niveau de la mer , est le point le plus élevé de la côte est au sud du Maine . [143] Le sommet de la crête est principalement couvert de bois dans le cadre de la ceinture de verdure de Staten Island . [144]

Arrondissements

1.Manhattan 2.Brooklyn 3. Reines 4. Le Bronx 5. Staten Island

1.Manhattan 2.Brooklyn 3. Reines 4. Le Bronx 5. Staten Island

Les cinq arrondissements de New York

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juridiction | Population | PIB † | Aire d’atterrissage | Densité de population | |||

| Arrondissement | Comté | Recensement (2020) |

milliards (USD 2012) |

milles carrés |

km2 _ |

personnes/ km 2 |

personnes / km 2 |

| Le Bronx | Bronx | 1 472 654 | 42,695 $ | 42.2 | 109.3 | 34 920 | 13 482 |

| Brooklyn | rois | 2 736 074 | 91,559 $ | 69,4 | 179,7 | 39 438 | 15 227 |

| Manhattan | New York | 1 694 263 | 600.244 $ | 22,7 | 58,8 | 74 781 | 28 872 |

| Reines | Reines | 2 405 464 | $ 93.310 | 108.7 | 281,5 | 22 125 | 8 542 |

| Staten Island | Richmond | 495 747 | $ 14.514 | 57,5 | 148,9 | 8 618 | 3 327 |

| Ville de New York | 8 804 190 | $ 842.343 | 302.6 | 783.8 | 29 095 | 11 234 | |

| État de New York | 20 215 751 | 1 731,910 $ | 47 126,4 | 122 056,8 | 429 | 166 | |

| † PIB = Produit Intérieur Brut Sources : [145] [146] [147] [148] et voir les articles individuels des arrondissements |

La ville de New York est parfois appelée collectivement les cinq arrondissements . [149] Chaque arrondissement est coextensif avec un comté respectif de l’État de New York , faisant de New York l’une des municipalités américaines dans plusieurs comtés . Il existe des centaines de quartiers distincts dans les arrondissements, dont beaucoup ont une histoire et un caractère définissables.

Si les arrondissements étaient chacun des villes indépendantes, quatre des arrondissements (Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan et le Bronx) seraient parmi les dix villes les plus peuplées des États-Unis (Staten Island serait classée 37e en 2020) ; ces mêmes arrondissements coïncident avec les quatre comtés les plus densément peuplés des États-Unis : New York (Manhattan), Kings (Brooklyn), Bronx et Queens.

Manhattan

Lower et Midtown Manhattan, vus par un satellite SkySat en 2017

Lower et Midtown Manhattan, vus par un satellite SkySat en 2017

Manhattan (comté de New York) est l’arrondissement géographiquement le plus petit et le plus densément peuplé. Il abrite Central Park et la plupart des gratte-ciel de la ville, et est parfois connu localement sous le nom de The City . [150] La densité de population de Manhattan de 72 033 personnes par mile carré (27 812/km 2 ) en 2015 en fait la plus élevée de tous les comtés des États-Unis et supérieure à la densité de n’importe quelle ville américaine individuelle . [151]

Manhattan est le centre culturel, administratif et financier de la ville de New York et contient le siège de nombreuses grandes sociétés multinationales , le siège des Nations Unies , Wall Street et un certain nombre d’universités importantes. L’arrondissement de Manhattan est souvent décrit comme le centre financier et culturel du monde. [152] [153]

La majeure partie de l’arrondissement est située sur l’île de Manhattan , à l’embouchure de la rivière Hudson. Plusieurs petites îles composent également une partie de l’arrondissement de Manhattan, notamment Randall’s Island , Wards Island et Roosevelt Island dans l’East River, ainsi que Governors Island et Liberty Island au sud dans le port de New York .

L’île de Manhattan est vaguement divisée en régions Lower , Midtown et Uptown . Uptown Manhattan est divisé par Central Park en l’ Upper East Side et l’ Upper West Side , et au-dessus du parc se trouve Harlem , bordant le Bronx (comté du Bronx).

Harlem était principalement occupée par des juifs et des italo-américains au 19ème siècle jusqu’à la Grande Migration . C’était le centre de la Renaissance de Harlem .

L’arrondissement de Manhattan comprend également un petit quartier sur le continent, appelé Marble Hill , qui est contigu au Bronx. Les quatre arrondissements restants de la ville de New York sont collectivement appelés les arrondissements extérieurs .

Dix milles (16 km) panorama sur les toits de Manhattan de la 120e rue à la batterie , pris en février 2018 de l’autre côté de la rivière Hudson à Weehawken, New Jersey .

Dix milles (16 km) panorama sur les toits de Manhattan de la 120e rue à la batterie , pris en février 2018 de l’autre côté de la rivière Hudson à Weehawken, New Jersey .

- Église au bord de la rivière

- Deutsche Bank Center

- 220 Central Park Sud

- Tour du parc central

- Un57

- 432, avenue du Parc

- 53W53

- Chrysler Building

- Tour de la Banque d’Amérique

- Bâtiment Condé Nast

- Le bâtiment du New York Times

- Empire State Building

- Manhattan Ouest

- a : 55 verges d’Hudson , 14b : 35 verges d’Hudson , 14c : 10 verges d’Hudson , 14d : 15 verges d’Hudson

- 56, rue Léonard

- 8, rue Spruce

- Édifice Woolworth

- 70, rue des Pins

- 30 place du parc

- 40 Wall Street

- Trois World Trade Center

- Quatre World Trade Center

- Un centre de commerce mondial

Brooklyn

Brooklyn (comté de Kings), à l’extrémité ouest de Long Island , est l’arrondissement le plus peuplé de la ville. Brooklyn est connue pour sa diversité culturelle, sociale et ethnique, une scène artistique indépendante, des quartiers distincts et un patrimoine architectural distinctif. Downtown Brooklyn est le plus grand quartier central des Outer Boroughs. L’arrondissement a un long littoral en bord de mer, y compris Coney Island , établi dans les années 1870 comme l’un des premiers terrains d’amusement aux États-Unis [154] Marine Park et Prospect Park sont les deux plus grands parcs de Brooklyn. [155] Depuis 2010, Brooklyn est devenu un centre prospère del’entrepreneuriat et les startups de haute technologie , [156] [157] et de l’art et du design postmodernes . [157] [158]

Skyline du centre-ville de Brooklyn depuis Governors Island en septembre 2016. Reines

Skyline du centre-ville de Brooklyn depuis Governors Island en septembre 2016. Reines

Queens (comté de Queens), sur Long Island au nord et à l’est de Brooklyn, est géographiquement le plus grand arrondissement, le comté le plus ethniquement diversifié des États-Unis [159] et la zone urbaine la plus ethniquement diversifiée au monde. [160] [161] Historiquement un ensemble de petites villes et de villages fondés par les Néerlandais, l’arrondissement a depuis développé une proéminence tant commerciale que résidentielle. Le centre-ville de Flushing est devenu l’un des quartiers centraux les plus animés des arrondissements extérieurs. Queens est le site de Citi Field , le stade de baseball des Mets de New York , et accueille le tournoi de tennis annuel US Openà Flushing Meadows-Corona Park . De plus, deux des trois aéroports les plus fréquentés desservant la région métropolitaine de New York, l’aéroport international John F. Kennedy et l’aéroport LaGuardia , sont situés dans le Queens. Le troisième est l’aéroport international de Newark Liberty à Newark , New Jersey.

Le Bronx

Le Bronx (comté du Bronx) est à la fois l’arrondissement le plus au nord de New York et le seul qui se trouve principalement sur le continent. C’est l’emplacement du Yankee Stadium , le parc de baseball des Yankees de New York , et abrite le plus grand complexe de logements coopératifs aux États-Unis, Co-op City . [162] Il abrite également le zoo du Bronx , le plus grand zoo métropolitain du monde, [163] qui s’étend sur 265 acres (1,07 km 2 ) et abrite plus de 6 000 animaux. [164] Le Bronx est aussi le berceau de la musique et de la culture hip hop . [165] Pelham Bay Park est le plus grand parc de New York, avec 2 772 acres (1 122 ha). [166]

Staten Island

Staten Island (comté de Richmond) est le plus suburbain des cinq arrondissements. Staten Island est reliée à Brooklyn par le pont Verrazano-Narrows et à Manhattan par le ferry gratuit de Staten Island , un ferry quotidien qui offre une vue imprenable sur la Statue de la Liberté , Ellis Island et Lower Manhattan. Dans le centre de Staten Island, la ceinture de verdure de Staten Island s’étend sur environ 2 500 acres (10 km 2 ), dont 28 miles (45 km) de sentiers pédestres et l’une des dernières forêts intactes de la ville. [167]Désignée en 1984 pour protéger les terres naturelles de l’île, la Ceinture de verdure comprend sept parcs municipaux.

-

![]()

![]()

La ligne d’horizon croissante de Long Island City , Queens (arrière-plan), [168] face à l’ East River et à Manhattan en mai 2017

-

![]()

![]()

Le Grand Concourse dans le Bronx , au premier plan, avec Manhattan en arrière-plan en février 2018

-

![]()

![]()

St. George, Staten Island vu depuis le Staten Island Ferry , le système de ferry réservé aux passagers le plus fréquenté au monde, faisant la navette entre Manhattan et Staten Island

Architecture

Dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre, à partir du coin supérieur gauche : l’ Empire State Building est une icône solitaire de New York, définie par ses revers , ses détails Art déco et sa flèche comme le plus haut bâtiment du monde de 1931 à 1970 ; le Chrysler Building , construit en 1930, est aussi une icône de Manhattan dans le style Art Déco , avec ses enjoliveurs ornementaux et sa flèche ; Architecture moderniste juxtaposée à l’architecture néo-gothique dans Midtown Manhattan ; et des maisons en rangée emblématiques du XIXe siècle , y compris les brownstones , sur la rue Kent bordée d’arbres dans le quartier historique de Greenpoint , à Brooklyn.

Dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre, à partir du coin supérieur gauche : l’ Empire State Building est une icône solitaire de New York, définie par ses revers , ses détails Art déco et sa flèche comme le plus haut bâtiment du monde de 1931 à 1970 ; le Chrysler Building , construit en 1930, est aussi une icône de Manhattan dans le style Art Déco , avec ses enjoliveurs ornementaux et sa flèche ; Architecture moderniste juxtaposée à l’architecture néo-gothique dans Midtown Manhattan ; et des maisons en rangée emblématiques du XIXe siècle , y compris les brownstones , sur la rue Kent bordée d’arbres dans le quartier historique de Greenpoint , à Brooklyn.

New York possède des bâtiments remarquables sur le plan architectural dans un large éventail de styles et de périodes distinctes, de la maison coloniale néerlandaise Pieter Claesen Wyckoff à Brooklyn, dont la partie la plus ancienne date de 1656, au moderne One World Trade Center , le gratte-ciel de Ground Zéro dans le Lower Manhattan et la tour de bureaux la plus chère au monde en termes de coût de construction. [169]

La ligne d’ horizon de Manhattan , avec ses nombreux gratte-ciel, est universellement reconnue, et la ville a abrité plusieurs des bâtiments les plus hauts du monde . En 2019 [update], la ville de New York comptait 6 455 immeubles de grande hauteur, le troisième au monde après Hong Kong et Séoul . [170] Parmi ceux-ci, en 2011 [update], 550 structures achevées mesuraient au moins 330 pieds (100 m) de haut, avec plus de cinquante gratte-ciel achevés de plus de 656 pieds (200 m) . Il s’agit notamment du Woolworth Building , un des premiers exemples d’ architecture néo-gothiquedans la conception de gratte-ciel, construit avec des détails gothiques à grande échelle ; achevé en 1913, il a été pendant 17 ans le plus haut bâtiment du monde. [171]

La résolution de zonage de 1916 exigeait des retraits dans les nouveaux bâtiments et limitait les tours à un pourcentage de la taille du terrain , pour permettre à la lumière du soleil d’atteindre les rues en contrebas. [172] Le style Art déco du Chrysler Building (1930) et de l’Empire State Building (1931), avec leurs sommets effilés et leurs flèches en acier , reflétait les exigences de zonage. Les bâtiments ont des ornements distinctifs, tels que les aigles aux coins du 61e étage du Chrysler Building, et sont considérés comme l’un des plus beaux exemples du style Art Déco . [173] Un exemple très influent de lastyle international aux États-Unis est le Seagram Building (1957), qui se distingue par sa façade utilisant des poutres en I visibles de couleur bronze pour évoquer la structure du bâtiment. Le Condé Nast Building (2000) est un exemple frappant de conception verte dans les gratte-ciel américains [174] et a reçu un prix de l’ American Institute of Architects et de l’AIA New York State pour sa conception.

Le caractère des grands quartiers résidentiels de New York est souvent défini par les élégantes maisons en rangée et les maisons de ville en grès brun et les immeubles miteux qui ont été construits pendant une période d’expansion rapide de 1870 à 1930. [175] En revanche, la ville de New York a également des quartiers qui sont moins densément peuplées et dotées d’habitations indépendantes. Dans des quartiers tels que Riverdale (dans le Bronx), Ditmas Park (à Brooklyn) et Douglaston (dans le Queens), les grandes maisons unifamiliales sont courantes dans divers styles architecturaux tels que Tudor Revival et Victorian . [176] [177][178]

La pierre et la brique sont devenues les matériaux de construction de choix de la ville après que la construction de maisons à ossature de bois ait été limitée à la suite du grand incendie de 1835 . [179] Un trait distinctif de nombreux bâtiments de la ville est le château d’eau en bois monté sur le toit . Dans les années 1800, la ville a exigé leur installation sur des bâtiments de plus de six étages pour éviter le besoin de pressions d’eau excessivement élevées à basse altitude, ce qui pourrait casser les conduites d’eau municipales. [180] Les appartements avec jardin sont devenus populaires au cours des années 1920 dans les zones périphériques, telles que Jackson Heights . [181]

Selon le United States Geological Survey , une analyse mise à jour du risque sismique en juillet 2014 a révélé un “risque légèrement inférieur pour les immeubles de grande hauteur” à New York que précédemment évalué. Les scientifiques ont estimé ce risque réduit sur la base d’une probabilité plus faible qu’on ne le pensait auparavant de secousses lentes près de la ville, ce qui serait plus susceptible d’endommager les structures plus hautes d’un tremblement de terre à proximité de la ville. [182]

Climat

| La ville de New York | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carte climatique ( explication ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Selon la classification climatique de Köppen , utilisant l’isotherme de 0 ° C (32 ° F), New York présente un climat subtropical humide (Cfa) et est donc la grande ville la plus septentrionale du continent nord-américain avec cette catégorisation. Les banlieues au nord et à l’ouest immédiats se situent dans la zone de transition entre les climats subtropicaux humides et continentaux humides (Dfa). [183] [184] Selon la classification de Trewartha , la ville est définie comme ayant un climat océanique (Do). [185] [186] Annuellement, la ville compte en moyenne 234 jours avec au moins un peu de soleil. [187] La ville se situe dans la zone de rusticité des plantes USDA 7b .[188]

Central Park en hiver par Raymond Speers, dans Munsey’s Magazine , février 1900

Central Park en hiver par Raymond Speers, dans Munsey’s Magazine , février 1900

Les hivers sont froids et humides, et les vents dominants qui soufflent les brises marines au large atténuent les effets modérateurs de l’océan Atlantique; Pourtant, l’Atlantique et le blindage partiel de l’air plus froid par les Appalaches maintiennent la ville plus chaude en hiver que les villes nord-américaines intérieures à des latitudes similaires ou inférieures telles que Pittsburgh , Cincinnati et Indianapolis . La température moyenne quotidienne en janvier, le mois le plus froid de la région, est de 33,7 ° F (0,9 ° C). [189] Les températures chutent généralement à 10 °F (−12 °C) plusieurs fois par hiver, [190]mais peut également atteindre 60 ° F (16 ° C) pendant plusieurs jours, même pendant le mois d’hiver le plus froid. Le printemps et l’automne sont imprévisibles et peuvent aller du froid au chaud, bien qu’ils soient généralement doux avec une faible humidité. Les étés sont généralement chauds et humides, avec une température moyenne quotidienne de 77,5 ° F (25,3 ° C) en juillet. [189]

Les températures nocturnes sont souvent améliorées en raison de l’ effet d’îlot de chaleur urbain . Les températures diurnes dépassent 90 ° F (32 ° C) en moyenne 17 jours chaque été et certaines années dépassent 100 ° F (38 ° C), bien qu’il s’agisse d’une réalisation rare, survenue pour la dernière fois le 18 juillet 2012. [191] De même, les lectures de 0 °F (−18 °C) sont également extrêmement rares, la dernière ayant eu lieu le 14 février 2016. [192] Les températures extrêmes ont varié de −15 °F (−26 °C), enregistrées le 9 février, 1934, jusqu’à 106 ° F (41 ° C) le 9 juillet 1936; [189] le refroidissement éolien le plus froid enregistré était de -37 ° F (-38 ° C) le même jour que le plus bas record de tous les temps. [193]Le maximum quotidien record de froid était de 2 ° F (−17 ° C) le 30 décembre 1917, tandis qu’à l’inverse, le minimum quotidien record de chaleur était de 87 ° F (31 ° C), le 2 juillet 1903. [191] la température moyenne de l’eau de l’océan Atlantique voisin varie de 39,7 ° F (4,3 ° C) en février à 74,1 ° F (23,4 ° C) en août. [194]

La ville reçoit 49,5 pouces (1 260 mm) de précipitations par an, qui sont relativement uniformément réparties tout au long de l’année. Les chutes de neige hivernales moyennes entre 1991 et 2020 ont été de 29,8 pouces (76 cm); cela varie considérablement d’une année à l’autre. Les ouragans et les tempêtes tropicales sont rares dans la région de New York. [195] L’ouragan Sandy a provoqué une onde de tempête destructrice à New York dans la soirée du 29 octobre 2012, inondant de nombreuses rues, tunnels et lignes de métro dans le Lower Manhattan et d’autres quartiers de la ville et coupant l’électricité dans de nombreuses parties du ville et sa banlieue. [196] La tempête et ses impacts profonds ont suscité la discussion sur la construction de digueset d’autres barrières côtières autour des rives de la ville et de la zone métropolitaine afin de minimiser le risque de conséquences destructrices d’un autre événement de ce type à l’avenir. [197] [198]

Le mois le plus froid jamais enregistré est janvier 1857, avec une température moyenne de 19,6 °F (−6,9 °C) tandis que les mois les plus chauds jamais enregistrés sont juillet 1825 et juillet 1999, tous deux avec une température moyenne de 81,4 °F (27,4 °C) . [199] Les années les plus chaudes jamais enregistrées sont 2012 et 2020, toutes deux avec des températures moyennes de 57,1 °F (13,9 °C). L’année la plus froide est 1836, avec une température moyenne de 47,3 ° F (8,5 ° C). [199] [200] Le mois le plus sec jamais enregistré est juin 1949, avec 0,02 pouces (0,51 mm) de précipitations. Le mois le plus humide a été août 2011, avec 18,95 pouces (481 mm) de précipitations. L’année la plus sèche jamais enregistrée est 1965, avec 26,09 pouces (663 mm) de précipitations. L’année la plus humide a été 1983, avec 80,56 pouces (2 046 mm) de précipitations. [201]Le mois le plus enneigé jamais enregistré est février 2010, avec 36,9 pouces (94 cm) de chutes de neige. La saison la plus enneigée (juillet-juin) enregistrée est 1995-1996, avec 75,6 pouces (192 cm) de chutes de neige. La saison la moins enneigée a été 1972-1973, avec 2,3 pouces (5,8 cm) de chutes de neige. [202] La première trace saisonnière de chute de neige s’est produite le 10 octobre, en 1979 et 1925. La dernière trace saisonnière de chute de neige s’est produite le 9 mai, en 2020 et 1977. [203]

Données climatiques pour New York ( Château du Belvédère , Central Park ), normales de 1991 à 2020, [a] extrêmes de 1869 à aujourd’hui [b] |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | Fév | Mar | Avr | Mai | Juin | Juil | Août | Sep | Oct | Nov | Déc | An |

| Record élevé °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Moyenne maximale °F (°C) | 60,4 (15,8) |

60,7 (15,9) |

70,3 (21,3) |

82,9 (28,3) |

88,5 (31,4) |

92,1 (33,4) |

95,7 (35,4) |

93,4 (34,1) |

89,0 (31,7) |

79,7 (26,5) |

70,7 (21,5) |

62,9 (17,2) |

97,0 (36,1) |

| Moyenne élevée °F (°C) | 39,5 (4,2) |

42,2 (5,7) |

49,9 (9,9) |

61,8 (16,6) |

71,4 (21,9) |

79,7 (26,5) |

84,9 (29,4) |

83,3 (28,5) |

76,2 (24,6) |

64,5 (18,1) |

54,0 (12,2) |

44.3 (6,8) |

62,6 (17,0) |

| Moyenne quotidienne °F (°C) | 33,7 (0,9) |

35,9 (2,2) |

42,8 (6,0) |

53,7 (12,1) |

63.2 (17,3) |

72,0 (22,2) |

77,5 (25,3) |

76.1 (24,5) |

69.2 (20,7) |

57,9 (14,4) |

48,0 (8,9) |

39.1 (3,9) |

55,8 (13,2) |

| Moyenne basse °F (°C) | 27,9 (−2,3) |

29,5 (−1,4) |

35,8 (2,1) |

45,5 (7,5) |

55,0 (12,8) |

64,4 (18,0) |

70,1 (21,2) |

68,9 (20,5) |

62,3 (16,8) |

51,4 (10,8) |

42,0 (5,6) |

33,8 (1,0) |

48,9 (9,4) |

| Minimum moyen °F (°C) | 9,8 (−12,3) |

12,7 (−10,7) |

19,7 (−6,8) |

32,8 (0,4) |

43,9 (6,6) |

52,7 (11,5) |

61,8 (16,6) |

60,3 (15,7) |

50,2 (10,1) |

38,4 (3,6) |

27,7 (−2,4) |

18,0 (−7,8) |

7,7 (−13,5) |

| Record bas °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

−15 (−26) |

3 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

32 (0) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

5 (−15) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Précipitations moyennes pouces (mm) | 3,64 (92) |

3.19 (81) |

4,29 (109) |

4,09 (104) |

3,96 (101) |

4,54 (115) |

4.60 (117) |

4,56 (116) |

4.31 (109) |

4.38 (111) |

3.58 (91) |

4.38 (111) |

49,52 (1 258) |

| Chute de neige moyenne en pouces (cm) | 8.8 (22) |

10.1 (26) |

5.0 (13) |

0,4 (1,0) |

0,0 (0,0) |

0,0 (0,0) |

0,0 (0,0) |

0,0 (0,0) |

0,0 (0,0) |

0,1 (0,25) |

0,5 (1,3) |

4.9 (12) |

29,8 (76) |

| Jours de précipitations moyennes (≥ 0,01 po) | 10.8 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 125.4 |

| Jours de neige moyens (≥ 0,1 po) | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0,2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0,2 | 2.1 | 11.4 |

| Humidité relative moyenne (%) | 61,5 | 60.2 | 58,5 | 55.3 | 62,7 | 65.2 | 64.2 | 66,0 | 67,8 | 65,6 | 64,6 | 64.1 | 63,0 |

| Point de rosée moyen °F (°C) | 18,0 (−7,8) |

19,0 (−7,2) |

25,9 (−3,4) |

34,0 (1,1) |

47.3 (8,5) |

57,4 (14,1) |

61,9 (16,6) |

62,1 (16,7) |

55,6 (13,1) |

44,1 (6,7) |

34,0 (1,1) |

24,6 (−4,1) |

40,3 (4,6) |

| Heures d’ensoleillement mensuelles moyennes | 162.7 | 163.1 | 212.5 | 225.6 | 256.6 | 257.3 | 268.2 | 268.2 | 219.3 | 211.2 | 151,0 | 139,0 | 2 534,7 |

| Pourcentage d’ensoleillement possible | 54 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 59 | 63 | 59 | 61 | 51 | 48 | 57 |

| Indice ultraviolet moyen | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1 : NOAA (humidité relative et soleil 1961–1990 ; point de rosée 1965–1984) [191] [205] [187] [206] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2 : Atlas météorologique [207]

Voir Climat de New York pour des informations climatiques supplémentaires sur les arrondissements extérieurs. |

| Données de température de la mer pour New York | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | Fév | Mar | Avr | Mai | Juin | Juil | Août | Sep | Oct | Nov | Déc | An |

| Température moyenne de la mer °F (°C) | 41,7 (5,4) |

39,7 (4,3) |

40,2 (4,5) |

45,1 (7,3) |

52,5 (11,4) |

64,5 (18,1) |

72,1 (22,3) |

74,1 (23,4) |

70,1 (21,2) |

63,0 (17,2) |

54,3 (12,4) |

47,2 (8,4) |

55,4 (13,0) |

| Source : Atlas météorologique [207] |

Afficher ou modifier les données brutes du graphique .

Parcs

Flushing Meadows – Corona Park a été utilisé à la fois à l ‘ Exposition universelle de New York de 1939 et de 1964 , avec l ‘ Unisphere comme pièce maîtresse de cette dernière et qui reste aujourd’hui.

Flushing Meadows – Corona Park a été utilisé à la fois à l ‘ Exposition universelle de New York de 1939 et de 1964 , avec l ‘ Unisphere comme pièce maîtresse de cette dernière et qui reste aujourd’hui.

La ville de New York possède un système de parcs complexe, avec divers terrains exploités par le National Park Service , le New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation et le New York City Department of Parks and Recreation . Dans son classement ParkScore 2018, The Trust for Public Land a rapporté que le système de parcs de New York était le neuvième meilleur système de parcs parmi les cinquante villes américaines les plus peuplées. [208] ParkScore classe les systèmes de parcs urbains selon une formule qui analyse la taille médiane des parcs, la superficie des parcs en pourcentage de la superficie de la ville, le pourcentage de résidents de la ville à moins d’un demi-mile d’un parc, les dépenses des services du parc par résident et le nombre de aires de jeux pour 10 000 habitants.

parcs nationaux

La Statue de la Liberté sur Liberty Island dans le port de New York est un symbole des États-Unis et de ses idéaux de liberté, de démocratie et d’opportunités. [21]

La Statue de la Liberté sur Liberty Island dans le port de New York est un symbole des États-Unis et de ses idéaux de liberté, de démocratie et d’opportunités. [21]

La Gateway National Recreation Area s’étend sur plus de 26 000 acres (110 km 2 ) au total, la plupart entourée par la ville de New York, [209] y compris le Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge . À Brooklyn et dans le Queens, le parc contient plus de 9 000 acres (36 km 2 ) de marais salés , de zones humides , d’îles et d’eau, y compris la majeure partie de la baie de la Jamaïque . Toujours dans le Queens, le parc comprend une partie importante de la péninsule ouest de Rockaway , notamment le parc Jacob Riis et Fort Tilden . À Staten Island, la Gateway National Recreation Area comprend Fort Wadsworth, avec Battery Weed et Fort Tompkins , et Great Kills Park , avec des plages, des sentiers et une marina .

Le monument national de la Statue de la Liberté et le musée de l’immigration d’Ellis Island sont gérés par le National Park Service et se trouvent dans les États de New York et du New Jersey . Ils sont rejoints dans la rade par le Governors Island National Monument , à New York. Les sites historiques sous gestion fédérale sur l’île de Manhattan comprennent le Castle Clinton National Monument ; Mémorial national de la salle fédérale ; Lieu historique national du lieu de naissance de Theodore Roosevelt ; Mémorial national du général Grant (“Tombe de Grant”); Monument national du cimetière africain ; et le mémorial national de Hamilton Grange. Des centaines de propriétés privées sont inscrites au registre national des lieux historiques ou en tant que monument historique national , comme par exemple le Stonewall Inn , qui fait partie du monument national de Stonewall à Greenwich Village , en tant que catalyseur du mouvement moderne des droits des homosexuels . [115] [116] [117] [118] [119]

Parcs d’État

Il y a sept parcs d’État dans les limites de New York. Certains d’entre eux incluent:

- Le Clay Pit Ponds State Park Preserve est une zone naturelle qui comprend de vastes sentiers d’équitation .

- Riverbank State Park est une installation de 28 acres (11 ha) qui s’élève à 69 pieds (21 m) au-dessus de la rivière Hudson. [210]

- Marsha P. Johnson State Park est un parc d’État à Brooklyn et Manhattan qui borde l’East River qui a été renommé en l’honneur de Marsha P. Johnson. [211]

Parcs de la ville

Vue sur l’étang et Midtown Manhattan depuis le pont Gapstow à Central Park , l’une des attractions touristiques les plus visitées au monde, en 2019

Vue sur l’étang et Midtown Manhattan depuis le pont Gapstow à Central Park , l’une des attractions touristiques les plus visitées au monde, en 2019

La ville de New York compte plus de 28 000 acres (110 km 2 ) de parcs municipaux et 14 miles (23 km) de plages publiques. [212] Le plus grand parc municipal de la ville est Pelham Bay Park dans le Bronx, avec 2 772 acres (1 122 ha). [166] [213]

- Central Park , un parc de 843 acres (3,41 km 2 ) [166] dans le centre-haut de Manhattan, est le parc urbain le plus visité des États-Unis et l’un des lieux les plus filmés au monde, avec 40 millions de visiteurs en 2013. [214] Le parc a un éventail d’attractions ; il y a plusieurs lacs et étangs, deux patinoires , le zoo de Central Park , le Central Park Conservatory Garden et le réservoir Jackie Onassis de 106 acres (0,43 km 2 ) . [215] Les attractions d’intérieur incluent le château du Belvédèreavec son centre de la nature, le théâtre de marionnettes suédois Cottage et le carrousel historique. Le 23 octobre 2012, le gestionnaire de fonds spéculatifs John A. Paulson a annoncé un don de 100 millions de dollars au Central Park Conservancy , le plus important don monétaire jamais fait au système de parcs de New York. [216]

- Washington Square Park est un point de repère important dans le quartier de Greenwich Village , dans le Lower Manhattan. Le Washington Square Arch à l’entrée nord du parc est un symbole emblématique de l’Université de New York et de Greenwich Village.

- Prospect Park à Brooklyn possède une prairie de 90 acres (36 ha), un lac et de vastes forêts . Dans le parc se trouve l’historique Battle Pass, important dans la bataille de Long Island. [217]

- Flushing Meadows–Corona Park dans le Queens, avec ses 897 acres (363 ha) qui en font le quatrième plus grand parc de la ville, [218] a été le cadre de l’ Exposition universelle de 1939 et de l’ Exposition universelle de 1964 [219] et est l’hôte de l’ USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center et le tournoi annuel des championnats de tennis de l’US Open . [220]

- Plus d’un cinquième de la superficie du Bronx, soit 7 000 acres (28 km 2 ), est consacré à des espaces ouverts et à des parcs, notamment le parc Pelham Bay, le parc Van Cortlandt , le zoo du Bronx et les jardins botaniques de New York . [221]

- À Staten Island, le Conference House Park contient l’historique Conference House , site de la seule tentative de résolution pacifique de la Révolution américaine qui a été menée en septembre 1775, en présence de Benjamin Franklin représentant les Américains et Lord Howe représentant la Couronne britannique . [222] L’historique Burial Ridge , le plus grand cimetière amérindien de New York, se trouve dans le parc. [223]

Installations militaires

Brooklyn abrite Fort Hamilton , la seule installation de service actif de l’armée américaine à New York, [224] en dehors des opérations de la Garde côtière . L’installation a été établie en 1825 sur le site d’une petite batterie utilisée pendant la Révolution américaine , et c’est l’un des forts militaires les plus anciens d’Amérique. [225] Aujourd’hui, Fort Hamilton sert de quartier général à la Division de l’ Atlantique Nord du United States Army Corps of Engineerset pour le bataillon de recrutement de la ville de New York. Il abrite également la 1179th Transportation Brigade, le 722nd Aeromedical Staging Squadron et une station de traitement d’entrée militaire. Parmi les autres réserves militaires autrefois actives encore utilisées pour la Garde nationale et l’entraînement militaire ou les opérations de réserve dans la ville, citons Fort Wadsworth à Staten Island et Fort Totten dans le Queens.

Démographie

| Démographie historique | 2020 [226] | 2010 [227] | 1990 [228] | 1970 [228] | 1940 [228] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanc (non hispanique) | 30,9 % | 33,3 % | 43,4 % | 64,0 % | 92,1 % |

| Hispanique ou Latino | 28,3 % | 28,6 % | 23,7 % | 15,2 % | 1,6 % |

| Noir ou afro-américain (non hispanique) | 20,2 % | 22,8 % | 28,8 % | 21,1 % | 6,1 % |

| Asiatique et insulaire du Pacifique (non hispanique) | 15,6 % | 12,6 % | 7,0 % | 1,2 % | 0,2 % |

| Amérindien (non hispanique) | 0,2 % | 0,2 % | 0,4 % | 0,1 % | N / A |

| Deux races ou plus (non hispaniques) | 3,4 % | 1,8 % | N / A | N / A | N / A |

| An | Populaire. | ± % | |||

| 1698 | 4 937 | — | |||

| 1712 | 5 840 | +18,3% | |||

| 1723 | 7 248 | +24,1% | |||

| 1737 | 10 664 | +47,1% | |||

| 1746 | 11 717 | +9,9% | |||

| 1756 | 13 046 | +11,3% | |||

| 1771 | 21 863 | +67,6% | |||

| 1790 | 49 401 | +126,0% | |||

| 1800 | 79 216 | +60,4% | |||

| 1810 | 119 734 | +51,1% | |||

| 1820 | 152 056 | +27,0% | |||

| 1830 | 242 278 | +59,3% | |||

| 1840 | 391 114 | +61,4% | |||

| 1850 | 696 115 | +78,0% | |||

| 1860 | 1 174 779 | +68,8% | |||

| 1870 | 1 478 103 | +25,8% | |||

| 1880 | 1 911 698 | +29,3% | |||

| 1890 | 2 507 414 | +31,2% | |||

| 1900 | 3 437 202 | +37,1% | |||

| 1910 | 4 766 883 | +38,7% | |||

| 1920 | 5 620 048 | +17,9% | |||

| 1930 | 6 930 446 | +23,3% | |||

| 1940 | 7 454 995 | +7,6% | |||

| 1950 | 7 891 957 | +5,9% | |||

| 1960 | 7 781 984 | −1,4 % | |||

| 1970 | 7 894 862 | +1,5% | |||

| 1980 | 7 071 639 | −10,4 % | |||

| 1990 | 7 322 564 | +3,5% | |||

| 2000 | 8 008 278 | +9,4% | |||

| 2010 | 8 175 133 | +2,1% | |||

| 2020 | 8 804 190 | +7,7% | |||

| Remarque : Les chiffres du recensement (1790–2010) couvrent la superficie actuelle des cinq arrondissements, avant et après la consolidation de 1898. Pour New York même avant d’annexer une partie du Bronx en 1874, voir Manhattan # Demographics . [229] Source : Recensement décennal des États-Unis ; [230] 1698–1771 [231] 1790–1890 [229] [232] 1900–1990 [233] 2000–2010 [234] [235] [236] 2010–2020 [4] |

La ville de New York est la ville la plus peuplée des États-Unis, [237] avec 8 804 190 habitants [4] incorporant plus d’immigration dans la ville que d’émigration depuis le recensement américain de 2010 . [238] [239] Plus de deux fois plus de personnes vivent à New York qu’à Los Angeles , la deuxième ville américaine la plus peuplée, [237] et dans une zone plus petite. La ville de New York a gagné plus d’habitants entre 2010 et 2020 (629 000) que toute autre ville américaine, et un montant supérieur à la somme totale des gains au cours de la même décennie des quatre plus grandes villes américaines suivantes, Los Angeles, Chicago , Houston et Phoenix, Arizonacombiné. [240] [241] La population de New York est d’environ 44 % de la population de l’État de New York, [242] et d’environ 39 % de la population de la région métropolitaine de New York . [243] La majorité des résidents de New York en 2020 (5 141 538, soit 58,4 %) vivaient à Long Island , à Brooklyn ou dans le Queens. [244]

Densité de population

En 2017, la ville avait une densité de population estimée à 28 491 habitants par mile carré (11 000 / km 2 ), ce qui en fait la municipalité la plus densément peuplée du pays (de plus de 100 000), avec plusieurs petites villes (de moins de 100 000) dans le comté adjacent d’ Hudson, New Jersey ayant une plus grande densité , selon le recensement de 2010. [245] Géographiquement coextensif avec le comté de New York, la densité de population de l’arrondissement de Manhattan en 2017 de 72 918 habitants par mile carré (28 154/km 2 ) en fait la plus élevée de tous les comtés des États-Unis et supérieure à la densité de tout individu Ville américaine . [246] [247] [248][249] Les trois prochains comtés les plus denses des États-Unis, se classant deuxième à quatrième, sont également des arrondissements de New York : Brooklyn, le Bronx et le Queens respectivement. [250]

Race et ethnie

Une carte de la répartition raciale à New York, recensement américain de 2010. Chaque point représente 25 personnes : Blanc , Noir , Asiatique , Hispanique ou Autre (jaune).

Une carte de la répartition raciale à New York, recensement américain de 2010. Chaque point représente 25 personnes : Blanc , Noir , Asiatique , Hispanique ou Autre (jaune).

La population de la ville en 2020 était de 30,9% de blancs (non hispaniques), 28,7% d’hispaniques ou latinos , 20,2% de noirs ou d’afro-américains (non hispaniques), 15,6% ” a été inventé pour la première fois pour décrire les quartiers d’immigrants densément peuplés sur le d’asiatiques et 0,2% d’amérindiens (non hispaniques). [251] Au total, 3,4 % de la population non hispanique s’est identifiée à plus d’une race . Tout au long de son histoire, New York a été un important port d’entrée pour les immigrants aux États-Unis. Plus de 12 millions d’ immigrants européens ont été accueillis à Ellis Island entre 1892 et 1924. [252] Le terme « melting pot Lower East Side . En 1900, les Allemands constituaient le plus grand groupe d’immigrants, suivis des Irlandais , des Juifs et des Italiens . [253] En 1940, les Blancs représentaient 92 % de la population de la ville. [228 ]

Environ 37% de la population de la ville est née à l’étranger et plus de la moitié de tous les enfants sont nés de mères immigrées en 2013. [254] [255] À New York, aucun pays ou région d’origine ne domine. [254] Les dix plus grandes sources de personnes nées à l’étranger dans la ville en 2011 [update]étaient la République dominicaine , la Chine , le Mexique, la Guyane , la Jamaïque , l’Équateur , Haïti , l’Inde , la Russie et Trinité-et-Tobago , [256] tandis que les Bangladais -néela population immigrée est devenue l’une des plus dynamiques de la ville, comptant plus de 74 000 en 2011. [15] [257]

Dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre, à partir du haut à gauche : le Manhattan Chinatown ; la Petite Italie de Lower Manhattan ; le Harlem espagnol de l’Upper Manhattan ; Petite Inde, Queens ; la Petite Russie de Brooklyn ; Quartier coréen de Midtown Manhattan

Dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre, à partir du haut à gauche : le Manhattan Chinatown ; la Petite Italie de Lower Manhattan ; le Harlem espagnol de l’Upper Manhattan ; Petite Inde, Queens ; la Petite Russie de Brooklyn ; Quartier coréen de Midtown Manhattan

Selon le recensement de 2010, les Américains d’origine asiatique à New York sont plus d’un million, plus que les totaux combinés de San Francisco et de Los Angeles . [258] New York contient la population asiatique totale la plus élevée de toutes les villes américaines proprement dites. [259] L’arrondissement du Queens à New York abrite la plus grande population américaine d’origine asiatique de l’État et la plus grande population andine . ( colombienne , équatorienne , péruvienne et bolivienne ) des États-Unis, et est également la zone urbaine la plus ethniquement diversifiée des États-Unis. monde. [160] [161]

La population chinoise constitue la nationalité qui connaît la croissance la plus rapide dans l’État de New York ; plusieurs satellites du quartier chinois original de Manhattan , à Brooklyn , et autour de Flushing, dans le Queens , prospèrent en tant qu’enclaves traditionnellement urbaines, tout en s’étendant également rapidement vers l’est dans la banlieue du comté de Nassau [260] à Long Island , [261] en tant que région métropolitaine de New York et L’État de New York est devenu la première destination des nouveaux immigrants chinois, respectivement, et l’immigration chinoise à grande échelle se poursuit dans la ville de New York et ses environs, [262] [263] [264] [265] [266] [267]avec la plus grande diaspora chinoise métropolitaine en dehors de l’Asie, [15] [268] dont environ 812 410 personnes en 2015. [269]

En 2012, 6,3% de la ville de New York était d’ origine chinoise , dont près des trois quarts vivaient dans le Queens ou à Brooklyn, géographiquement sur Long Island. [270] Une communauté comptant 20 000 Coréens-Chinois ( Chaoxianzu ou Joseonjok ) est centrée à Flushing, dans le Queens , tandis que la ville de New York abrite également la plus grande population tibétaine en dehors de la Chine, de l’Inde et du groupe ethnique à 0,8 %, suivi par les Vietnamiens , qui représentaient 0,2% de la population de New York en 2010. Les Indiens sont le plus grand groupe d’Asie du Sud , comprenant 2,4% de la population de la ville, avec les Bangladais et du Népal , également centrée dans le Queens. [271] Les Coréens représentaient 1,2 % de la population de la ville et les Japonais 0,3 %. Les Philippins étaient le plus grand groupe d’Asie du Sud-Est les Pakistanais à 0,7% et 0,5%, respectivement. [272] Queens est l’arrondissement préféré des Indiens d’Asie, des Coréens, des Philippins et des Malais , [273] [262] et d’autres Asiatiques du Sud-Est ; [274] tandis que Brooklyn reçoit un grand nombre d’ immigrants antillais et asiatiques.