Histoire de l’Autriche

L’ histoire de l’Autriche couvre l’histoire de l’ Autriche et de ses États prédécesseurs, du début de l’âge de pierre à l’état actuel. Le nom Ostarrîchi (Autriche) est utilisé depuis 996 après JC quand il était un margravat du duché de Bavière et à partir de 1156 un duché indépendant (plus tard archiduché ) du Saint Empire romain germanique de la nation allemande ( Heiliges Römisches Reich 962–1806) .

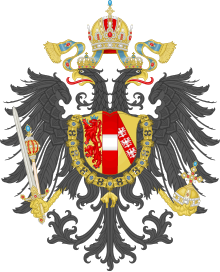

L’Autriche a été dominée par la maison de Habsbourg et la maison de Habsbourg-Lorraine ( Haus Österreich ) de 1273 à 1918. En 1806, lorsque l’empereur François II d’Autriche a dissous le Saint Empire romain germanique, l’Autriche est devenue l’ Empire autrichien et faisait également partie de la Confédération allemande jusqu’à la guerre austro-prussienne de 1866. En 1867, l’Autriche forme une double monarchie avec la Hongrie : l’ Empire austro-hongrois (1867-1918). Lorsque cet empire s’est effondré après la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale en 1918, l’Autriche a été réduite aux principales régions de l’empire, principalement germanophones (ses frontières actuelles), et a adopté le nom de République d’Autriche-Allemagne.. Cependant, l’union avec l’Allemagne et le nom du pays choisi ont été interdits par les Alliés lors du traité de Versailles . Cela a conduit à la création de la Première République autrichienne (1919-1933).

Après la Première République, l’ austrofascisme a tenté de maintenir l’indépendance de l’Autriche vis-à-vis du Reich allemand . Engelbert Dollfuss a admis que la plupart des Autrichiens étaient allemands et autrichiens, mais voulait que l’Autriche reste indépendante de l’Allemagne. En 1938, Adolf Hitler , d’origine autrichienne, annexa l’Autriche au Reich allemand avec l’ Anschluss , qui était soutenu par une grande majorité du peuple autrichien . [1] [2] Dix ans après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, l’Autriche est redevenue une république indépendante sous le nom de Deuxième République autrichienne en 1955.

L’Autriche a rejoint l’ Union européenne en 1995.

Historiographie

Étant donné que le territoire compris par le terme “Autriche” a subi des changements radicaux au fil du temps, traiter d’une Histoire de l’Autriche soulève un certain nombre de questions, par exemple, s’il est confiné à l’actuelle ou à l’ancienne République d’Autriche, ou s’étend également à toutes les terres autrefois gouverné par les souverains autrichiens. De plus, l’histoire autrichienne devrait-elle inclure la période 1938-1945, alors qu’elle n’existait pas théoriquement ? Parmi les terres qui font maintenant partie de la deuxième République d’Autriche, beaucoup ont été ajoutées au fil du temps – seulement deux des neuf provinces ou Bundesländer(Basse-Autriche et Haute-Autriche) sont strictement «Autriche», tandis que d’autres parties de son ancien territoire souverain font désormais partie d’autres pays, par exemple l’Italie, la Croatie, la Slovénie et la Tchéquie. En Autriche, il existe des affinités régionales et temporelles variables avec les pays voisins. [3]

Aperçu

L’habitation humaine du territoire actuel de l’Autriche remonte aux premières communautés agricoles du début de l’ âge de pierre ( ère paléolithique ). À la fin de l’âge du fer, il était occupé par des personnes de la culture celtique de Hallstatt (vers 800 avant JC), l’une des premières cultures celtiques en plus de la culture de La Tène en France. Ils se sont d’abord organisés en un royaume celtique appelé par les Romains Noricum , datant de c. 800 à 400 av. À la fin du 1er siècle avant JC, les terres au sud du Danube sont devenues une partie de l’ Empire romain et ont été incorporées sous le nom de Province de Noricum vers 40 après JC.

La colonie romaine la plus importante était à Carnuntum , qui peut encore être visitée aujourd’hui en tant que site de fouilles. Au 6e siècle, les Bavarii , un peuple germanique, occupèrent ces terres jusqu’à ce qu’elles tombent aux mains de l’ Empire franc au 9e siècle. Vers 800 après JC, Charlemagne a établi l’avant-poste de la Marche Avar ( Awarenmark ) dans ce qui est aujourd’hui la Basse-Autriche , pour retenir les avancées des Slaves et des Avars .

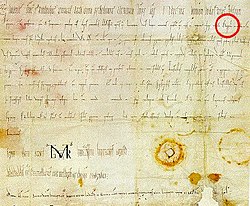

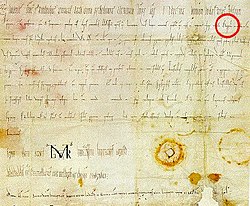

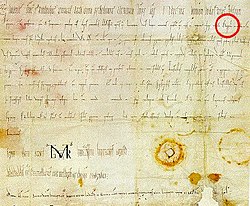

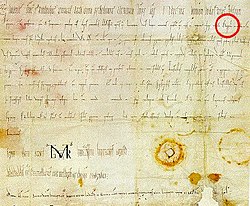

Le premier document contenant le mot “Ostarrîchi”, le mot est marqué d’un cercle rouge.

Le premier document contenant le mot “Ostarrîchi”, le mot est marqué d’un cercle rouge.

Au 10ème siècle, un avant-poste oriental (à l’est de la rivière Enns ) du duché de Bavière , à la frontière de la Hongrie , a été établi sous le nom de Marchia orientalis (Marche de l’Est) ou ‘ Margraviat d’Autriche ‘ en 976, gouverné par les Margraves de Babenberg . Cette ‘Marche Orientale’ (frontière), en allemand était connue sous le nom d’ Ostarrîchi ou ‘Royaume de l’Est’, d’où ‘l’Autriche ‘. La première mention d’ Ostarrîchi se produit dans un document de ce nom daté de 996 CE. A partir de 1156, l’empereur Frédéric Barberousse créa un duché indépendant ( Privilegium Minus ) sous laMaison de Babenberg , jusqu’à son extinction en 1246, correspondant à la Basse-Autriche moderne .

Après la dynastie Babenberg et un bref interrègne , l’Autriche passa sous le règne du roi allemand Rodolphe Ier de Habsbourg (1276-1282), commençant une dynastie qui durera sept siècles et se distinguera progressivement de la Bavière voisine , au sein du Saint Empire romain germanique . Le XVe et le début du XVIe siècle ont vu une expansion considérable des territoires des Habsbourg par la diplomatie et les mariages pour inclure l’Espagne, les Pays-Bas et certaines parties de l’Italie. Cet expansionnisme, ainsi que les aspirations françaises et la rivalité Habsbourg-Français ou Bourbon-Habsbourg qui en a résulté, ont été des facteurs importants qui ont façonné l’histoire européenne pendant plus de 200 ans (1516–1756).

Par l’ édit de Worms ( Wormser Vertrag ) du 28 avril 1521, l’empereur Charles Quint ( archiduc d’Autriche 1519-1521) divisa la dynastie, conférant les terres autrichiennes héréditaires ( Österreichische Länder ) à son frère, Ferdinand I (1521-1564) et les premières structures administratives centrales ont été établies. En 1526, Ferdinand avait également hérité des royaumes de Bohême et de Hongrie après la bataille de Mohács qui a divisé ce dernier. Cependant, l’ Empire ottoman était désormais directement adjacent aux terres autrichiennes. Même après l’échec du premier siège de Viennepar les Turcs en 1529, la menace ottomane persista encore un siècle et demi. Il y a eu une bataille où le roi polonais chrétien, Jean III Sobieski a arrêté l’attaque musulmane contre les chrétiens et la ville de Vienne en 1583.

Le XVIe siècle voit également la diffusion de la Réforme . À partir de 1600 environ, la politique de recatholicisation ou de renouveau catholique des Habsbourg ( Rekatholisierung ) a finalement conduit à la guerre de Trente Ans (1618–1648). À l’origine une guerre de religion, c’était aussi une lutte pour le pouvoir en Europe centrale, en particulier l’opposition française au Saint Empire romain germanique des Habsbourg. Finalement, la pression de la coalition anti-Habsbourg de la France, de la Suède et de la plupart des États allemands protestants a contenu leur autorité sur les terres autrichiennes et tchèques en 1648.

En 1683, les forces ottomanes ont été repoussées de Vienne une seconde fois et finalement, lors de la Grande Guerre de Turquie (1683-1699), repoussées au-delà de Belgrade . Lorsque la lignée principale (espagnole) des Habsbourg s’éteignit en 1700, elle précipita la guerre de Succession d’Espagne (1701-1714) entre les Habsbourg et le roi Louis XIV de France . Par la suite, l’Autriche prend le contrôle, par le traité d’Utrecht de 1713 , des Pays-Bas espagnols , de Naples et de la Lombardie .

Ces acquisitions ainsi que les conquêtes dans les Balkans ont donné à l’Autriche sa plus grande étendue territoriale à ce jour. 1713 vit également la Pragmatique Sanction , destinée à empêcher toute nouvelle division du territoire. Mais lorsque Charles VI (archiduc 1711-1740) mourut et fut remplacé par sa fille, Marie-Thérèse (1740-1780), l’Autriche fut perçue comme faible, ce qui conduisit à la guerre de Succession d’Autriche (1740-1748) et à la guerre de Sept Ans. (1756-1763). Par la suite, l’Autriche a perdu la Silésie au profit de la Prusse . L’Autriche a également perdu les conquêtes antérieures des Ottomans, à l’exception du Banat de Temeswar et de Syrmie dans leGuerre austro-russe-turque malgré son alliance avec la Russie.

Ces guerres de Silésie ont déclenché une tension de longue date entre l’Autriche et la Prusse. Marie-Thérèse a effectivement régné en tant qu’impératrice par l’intermédiaire de son mari, François Étienne de Lorraine (décédé en 1765) et ils ont fondé la nouvelle dynastie des Habsbourg-Lorraine. Pendant son règne, de vastes réformes ont été lancées et, à la mort de François en 1765, elles ont été poursuivies par son fils, Joseph II (empereur 1765–1790; archiduc 1780–1790). Cependant, son successeur, son frère, Léopold II (1790-1792), était beaucoup plus conservateur.

Le prochain empereur, son fils François II (1792–1835), se trouva en guerre avec la France lors des première (1792–1797) et deuxième (1798–1802) guerres de coalition, prélude aux guerres napoléoniennes (1803–1815), dans lequel l’Autriche a perdu de nouveaux territoires. À la suite de nouvelles pertes autrichiennes lors de la troisième guerre de coalition (1803–1806), l’avenir de l’empire des Habsbourg semblait de plus en plus incertain. Napoléon s’était déclaré empereur de France en mai 1804 et était occupé à réorganiser une grande partie des terres du Saint Empire romain germanique, et semblait également assumer le titre d’empereur, en tant que second Charlemagne. [4] [5] François II a répondu en proclamant laEmpire d’Autriche en août, prenant le nouveau titre d’Empereur. En 1806, après avoir occupé les deux titres par intérim, il a démissionné de la couronne impériale du Saint Empire romain germanique de la nation allemande, qui a alors cessé d’exister.

Après le Congrès de Vienne , l’Autriche est devenue une partie de la Confédération allemande jusqu’à la guerre austro-prussienne de 1866. Au XIXe siècle, les mouvements nationalistes au sein de l’empire sont devenus de plus en plus évidents et l’élément allemand s’est de plus en plus affaibli, tandis que la plupart des Italiens d’Autriche terres ont été acquises par le nouveau royaume d’Italie. Avec l’expulsion de l’Autriche de la Confédération allemande après sa défaite par la Prusse dans la guerre de 1866, la double monarchie avec la Hongrie a été créée par le compromis austro-hongrois en 1867. Cela a réussi à réduire mais pas à supprimer les tensions nationalistes car il a laissé principalement des peuples slaves etRoumains insatisfaits ; des insatisfactions qui devaient déborder avec l’assassinat en 1914 de l’héritier du trône d’Autriche-Hongrie, l’archiduc François-Ferdinand à Sarajevo , et la réaction en chaîne qui s’ensuivit aboutissant à la Première Guerre mondiale. Les pertes de la guerre ont entraîné l’effondrement de l’empire et de la dynastie en 1918.

Les groupes ethniques non allemands se sont séparés, laissant les frontières actuelles de l’Autriche sous le nom d’ Autriche allemande , qui a été proclamée république indépendante. La grave crise économique mondiale associée aux tensions politiques intérieures a conduit à des troubles civils en février 1934, la Constitution de mai de 1934 ayant abouti à un État corporatif autoritaire. À peine deux mois plus tard, les nazis autrichiens ont organisé le coup d’État de juillet , voulant annexer le pays à l’Allemagne nazie , entraînant l’assassinat du chancelier Engelbert Dollfuss . Alors que le coup d’État a échoué, Adolf Hitler a réussi à annexer l’Autriche le 12 mars 1938 sous le nom d’ Ostmark, jusqu’en 1945. L’Autriche a été divisée en quatre zones d’occupation après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, puis en 1955 est devenue l’État souverain indépendant ( Deuxième République ) qui a existé jusqu’à nos jours. En 1995, l’Autriche rejoint l’ Union européenne .

Géographie et géologie

Une carte topographique de l’Autriche.

Une carte topographique de l’Autriche.

Image satellite des régions géographiques de l’Autriche.

Image satellite des régions géographiques de l’Autriche.

L’état moderne de l’Autriche est considéré comme ayant trois zones géographiques. Le plus grand est constitué des Alpes , [a] qui couvre 62,8% de la masse continentale du pays. [6] Au nord, de l’autre côté du Danube , se trouve la partie autrichienne (sud) du massif de Bohême , appelée ” Böhmerwald ” ou forêt de Bohême , une chaîne de montagnes de granit relativement inférieure qui représente encore 10 % de la superficie des terres autrichiennes. . [b] [6] Les parties restantes du pays sont les basses terres pannoniennes le long de la frontière avec la Hongrie (11,3%) et le bassin de Vienne(4,4%). [6]

Le Massif de Bohême et ses contreforts se sont formés au cours de l’ orogenèse varisque de la fin du Paléozoïque . Un autre élément important de la géologie et de la géographie autrichiennes est l’ orogenèse alpine du Mésozoïque tardif et la formation subséquente de l’ océan Paratéthys et du bassin de la Molasse à l’ ère du Crétacé .

Les vastes régions alpines sont peu peuplées et forment une barrière au passage des peuples en dehors des cols stratégiques donnant accès à l’ Italie . L’Autriche est positionnée entre les pays d’Europe orientale et l’Europe centrale et occidentale, une position qui a dicté une grande partie de son histoire. La vallée du Danube a toujours été un corridor important de l’Ouest vers les Balkans et l’ Orient . [7] [8] [9]

Préhistoire et histoire ancienne

Paléolithique

La Vénus de Willendorf , ch. 25 000 avant JC. Naturhistorisches Museum , Vienne.

La Vénus de Willendorf , ch. 25 000 avant JC. Naturhistorisches Museum , Vienne.

Les Alpes étaient inaccessibles pendant la période glaciaire , de sorte que l’habitation humaine ne date pas d’avant l’ ère du Paléolithique moyen , à l’époque des Néandertaliens . Les plus anciennes traces d’habitation humaine en Autriche, il y a plus de 250 000 ans, ont été trouvées dans la grotte de Repolust à Badl, près de Peggau dans le district de Graz-Umgebung en Styrie . Ceux-ci comprennent des outils en pierre, des outils en os et des fragments de poterie ainsi que des restes de mammifères. Des preuves vieilles de 70 000 ans ont été trouvées dans la grotte de Gudenus, dans le nord-ouest de la Basse-Autriche.

Les vestiges du Paléolithique supérieur sont plus nombreux en Basse-Autriche. Les plus connus se trouvent dans la région de la Wachau , notamment les sites des deux plus anciennes œuvres d’art d’Autriche. Ce sont des représentations figuratives de femmes, la Vénus de Galgenberg trouvée près de Stratzing et estimée à 32 000 ans, et la Vénus voisine de Willendorf (26 000 ans) trouvée à Willendorf , près de Krems an der Donau . En 2005 dans la même zone, une sépulture double infantile a été découverte à Krems-Wachtberg, datant de la culture gravettienne (27 000 ans), la plus ancienne sépulture découverte en Autriche à ce jour. [10] [11]

Mésolithique

Les vestiges mésolithiques comprennent des abris sous roche (abris) du lac de Constance et de la vallée du Rhin alpin , un site funéraire à Elsbethen et quelques autres sites avec des artefacts microlithiques qui démontrent la transition de la vie de chasseurs-cueilleurs et d’agriculteurs et d’éleveurs sédentaires.

Néolithique

Au néolithique , la plupart des régions d’Autriche propices à l’agriculture et sources de matières premières ont été colonisées. Les vestiges comprennent ceux de la culture de la poterie linéaire , l’une des premières cultures agraires d’Europe. La première colonie rurale enregistrée à cette époque était à Brunn am Gebirge à Mödling . Le premier monument industriel d’Autriche, la mine de chert de Mauer-Antonshöhe dans le quartier Mauer du district sud de Vienne de Liesing date de cette période. Dans la culture Lengyel , qui a suivi la poterie linéaire en Basse-Autriche,des fossés circulaires ont été construits.

Âge du Cuivre

Des traces de l’ âge du cuivre (ère chalcolithique) en Autriche ont été identifiées dans le trésor du bassin des Carpates à Stollhof , Hohe Wand , Basse-Autriche. Les colonies perchées de cette époque sont courantes dans l’est de l’Autriche. Pendant ce temps, les habitants ont recherché et développé des matières premières dans les zones alpines centrales. La découverte la plus importante est considérée comme l’Iceman Ötzi , une momie bien conservée d’un homme gelé dans les Alpes datant d’environ 3 300 avant JC, bien que ces découvertes se trouvent maintenant en Italie à la frontière autrichienne. Une autre culture est le groupe Mondsee , représenté par des maisons sur pilotis dans les lacs alpins.

L’Âge de bronze

Au début de l’ âge du bronze, des fortifications apparaissaient, protégeant les centres commerciaux de l’extraction, de la transformation et du commerce du cuivre et de l’ étain . Cette culture florissante se reflète dans les artefacts funéraires, comme à Pitten, à Nußdorf ob der Traisen , en Basse-Autriche. À la fin de l’âge du bronze est apparue la culture Urnfield , dans laquelle l’extraction du sel a commencé dans les mines de sel du nord à Hallstatt .

L’âge de fer

L’ âge du fer en Autriche est représenté par la culture Hallstatt , qui a succédé à la culture Urnfield, sous les influences des civilisations méditerranéennes et des peuples des steppes . Cela s’est progressivement transformé en culture celtique de La Tène .

Culture de Hallstatt

Hallstatt (800 BC : jaune solide ; 500 BC : jaune clair) et La Tène (450 BC : vert solide ; 50 BC vert clair)

Hallstatt (800 BC : jaune solide ; 500 BC : jaune clair) et La Tène (450 BC : vert solide ; 50 BC vert clair)

Cette culture du début de l’ âge du fer porte le nom de Hallstatt , le site type de la Haute – Autriche . La culture est souvent décrite en deux zones, occidentale et orientale, traversées par les rivières Enns , Ybbs et Inn . La région de West Hallstatt était en contact avec les colonies grecques de la côte ligurienne . Dans les Alpes, les contacts avec les Étrusques et les régions sous influence grecque d’Italie sont maintenus. L’Orient avait des liens étroits avec les peuples des steppes qui avaient traversé le bassin des Carpates depuis les steppes du sud de la Russie.

La population de Hallstatt tirait sa richesse de l’industrie du sel. Des importations de produits de luxe s’étendant des mers du Nord et de la Baltique vers l’Afrique ont été découvertes dans le cimetière de Hallstatt. La plus ancienne preuve d’une industrie viticole autrichienne a été découverte à Zagersdorf , dans le Burgenland , dans un tumulus funéraire. Le Cult Wagon de Strettweg , en Styrie , témoigne de la vie religieuse contemporaine.

Culture La Tène (Celtique)

Au dernier âge du fer , la culture celtique de La Tène se répandit en Autriche. Cette culture a donné naissance aux premiers noms tribaux locaux enregistrés ( Taurisci , Ambidravi , Ambisontes ) et toponymes. De là est né Noricum (IIe siècle à environ 15 av . J.-C. ) – une confédération de tribus celtiques alpines (traditionnellement douze) sous la direction des Norici . Il était confiné au sud et à l’est de l’Autriche actuelle et à une partie de la Slovénie . L’Ouest a été colonisé par les Raeti .

Dürrnberg et Hallein (Salzbourg) étaient des colonies de sel celtiques. Dans l’est de la Styrie et le Burgenland (par exemple, Oberpullendorf ), du minerai de fer de haute qualité était extrait et traité, puis exporté vers les Romains sous le nom de ferrum noricum ( fer norique ). Cela a conduit à la création d’un avant-poste commercial romain sur le Magdalensberg au début du 1er siècle avant JC , remplacé plus tard par la ville romaine Virunum. Villages fortifiés perchés ( oppida ), par exemple Kulm (est de la Styrie ), Idunum (mod. Villach ), Burg ( Schwarzenbach), et Braunsberg ( Hainburg ), étaient des centres de la vie publique. Certaines villes comme Linz ( Lentos ) datent également de cette période.

Époque romaine

La province de Noricum mise en évidence au sein de l’ Empire romain .

La province de Noricum mise en évidence au sein de l’ Empire romain .

Bien que Noricum et Rome aient été des partenaires commerciaux actifs et aient formé des alliances militaires, vers 15 av. Dans le 19ème siècle). Noricum est devenu une province de l’ Empire romain .

Sous le règne de l’ empereur Claude (41-54 après JC), la province romaine de Noricum avait pour limites au nord le Danube , au nord-est les bois de Vienne et à l’est approximativement la frontière orientale actuelle de la Styrie , tandis qu’au sud-est et au sud, il était délimité par les rivières Eisack et Drava . Plus tard, sous Dioclétien (284-305), la province a été divisée le long de la crête principale des Alpes en une partie nord ( Noricum ripense ) et une partie sud ( Noricum Mediterraneum ). De l’autre côté du Ziller à l’ouest, correspondant aux provinces actuelles du Vorarlberget le Tyrol , étendent la province de Raetia , incorporant le territoire plus tôt de Vindelicia . A l’est s’étendait la Pannonie , y compris ce qui est aujourd’hui le Burgenland . Au sud se trouvait la Région 10, Venetia et Histria . [12] Le fleuve Danube a formé les limes danubiennes ( limes Danubii ), une ligne défensive séparant la Haute et la Basse Autriche des tribus germaniques des Marcomanni et des Quadi .

Les Romains ont construit de nombreuses villes qui survivent aujourd’hui. Ils comprennent Vindobona ( Vienne ), Juvavum ( Salzbourg ), Valdidena ( Innsbruck ) et Brigantium ( Brégence ). [13] D’autres villes importantes étaient Virunum (au nord du Klagenfurt moderne ), Teurnia (près de Spittal ) et Lauriacum ( Enns ). Les sites archéologiques importants de la période romaine comprennent Kleinklein (Styrie) et Zollfeld ( Magdalensberg ).

Le christianisme est apparu en Autriche au 2ème siècle après JC, incitant l’organisation de l’Église qui remonte au 4ème siècle après JC. Après l’arrivée des Bavarii , l’Autriche est devenue l’objet d’efforts missionnaires, comme Rupert et Virgil de la mission Hiberno-Scottish .

Période de migration

Routes des invasions babares, 100–500 après JC . Première phase : Goths, 300-500 après JC

Routes des invasions babares, 100–500 après JC . Première phase : Goths, 300-500 après JC

La Grande Migration ( Völkerwanderung ) scelle le déclin de la puissance romaine en Autriche. Dans la première phase (300-500 après JC), l’Empire romain a été de plus en plus harcelé par les tribus germaniques du 5ème siècle, y compris les Goths et les Vandales . Alors que le tissu de l’Empire romain s’effondrait, la capacité de Raetia, Noricum et Pannonia à se défendre devenait de plus en plus problématique. Radagaisus a envahi une partie du pays en 405. (Géza Alföldy pp. 213–4). Après plusieurs raids sur l’Italie, les Wisigoths arrivent en 408, sous Alaric I . [14]

Comme décrit par Zosime , Alaric partit d’ Emona ( Ljubljana moderne ) qui se trouvait entre la Pannonie supérieure et Noricum sur les Alpes carniques arrivant à Virunum dans Noricum, comme cela avait été convenu par le général romain Stilicho , après plusieurs escarmouches entre les deux. Alaric a été voté une grosse somme d’argent pour maintenir la paix, par le Sénat romain, à l’instigation de Stilicon . [14] De là, il dirigea ses opérations contre l’Italie, exigeant Noricum parmi un autre territoire, saccageant finalement Rome en 410 mais mourant sur le chemin du retour cette année-là. [15]

Les Wisigoths ont finalement déménagé, permettant une courte période de stabilité en dehors des troubles domestiques en 431. (Alföldy p. 214). 451 a vu les Huns traverser le pays et en 433, la Pannonie a dû être évacuée sous les attaques des Huns. La mort d’ Attila en 453 permit aux Ostrogoths de disperser son empire Hunnish. De nombreuses tribus, autrefois sous les Huns, ont maintenant commencé à s’installer le long du bassin du Danube et à affirmer leur indépendance. Parmi ceux-ci se trouvaient les Rugii , qui formèrent leurs propres terres ( Rugiland ) de l’autre côté du Danube et commencèrent à imposer leur volonté à Noricum.

À partir de 472 , les Ostrogoths et les Alamans envahissent la région mais ne la soumettent pas. Même après qu’Odoacre eut renversé le dernier empereur romain d’Occident en 476, il restait des vestiges de l’administration romaine dans les provinces avant l’effondrement final de l’Antiquité tardive dans cette région (voir Severinus de Noricum et Flaccitheus). Noricum a finalement été abandonné en 488, [16] tandis que Raetia a été abandonnée par les Romains aux Alamans .

Les villes et les bâtiments abandonnés et dévastés tombèrent lentement en désarroi au cours des 4e et 5e siècles. En 493, la région faisait partie des terres du roi Ostrogoth Théodoric et il ne restait plus d’influences romaines. L’effondrement de l’empire Ostrogoth a commencé avec sa mort en 526.

Deuxième phase: Slaves et Bavarii, 500–700 après JC

Au cours de la deuxième phase de la période de migration (500–700 après JC), les Langobardii ( Lombards ) ont fait une brève apparition dans les régions du nord et de l’est vers 500 après JC, mais avaient été chassés vers le nord de l’Italie par les Avars en 567. Les Avars et leurs vassaux slaves s’étaient établis de la mer Baltique aux Balkans . [17] Après que les Avars aient subi des revers à l’est en 626, les Slaves se sont rebellés, établissant leurs propres territoires. Les Slaves alpins ( Carantanii ) ont élu un Bavarois, Odilo , comme comte et ont résisté avec succès à une nouvelle subjugation Avar.

La tribu slave des Carantaniens a migré vers l’ouest le long de la Drava dans les Alpes orientales à la suite de l’expansion de leurs seigneurs Avar au 7ème siècle, mélangés à la population celto-romane, et a établi le royaume de Carantanie (plus tard Carinthie ), qui couvrait une grande partie du territoire autrichien oriental et central et était le premier État slave indépendant en Europe, centré à Zollfeld . Avec la population indigène, ils ont pu résister à un nouvel empiétement des Francs et Avars voisins dans les Alpes du sud-est.

Entre-temps, la tribu germanique des Bavarii (Bavarois), vassaux des Francs , s’était développée aux Ve et VIe siècles dans l’ouest du pays et dans ce qu’on appelle aujourd’hui la Bavière , tandis que ce qui est aujourd’hui le Vorarlberg s’était installé . par les Alémans . Dans les Alpes du Nord, les Bavarois s’étaient établis en tant que duché de tige vers 550 après JC, sous le règne des Agilolfings jusqu’en 788 en tant qu’avant-poste oriental de l’ Empire franc . A cette époque, les terres occupées par les Bavarois s’étendaient au sud jusqu’à l’actuel Tyrol du Sud , et à l’est jusqu’à la rivière Enns . Le centre administratif était àRatisbonne . Ces groupes se mêlèrent à la population rhéto-romane et la poussèrent dans les montagnes le long du Val Pusteria . [18]

Dans le sud de l’Autriche actuelle, les tribus slaves s’étaient installées dans les vallées de la Drava, de la Mura et de la Save en 600 après JC. La migration slave vers l’ouest a arrêté davantage la migration bavaroise vers l’est en 610. Leur expansion la plus à l’ouest a été atteinte en 650 dans la vallée de Puster ( Pustertal ), mais est progressivement retombée sur la rivière Enns en 780. [17] La frontière de peuplement entre les Slaves et les Bavarois approximativement correspond à une ligne de Freistadt à Linz , Salzbourg ( Lungau ), jusqu’au Tyrol oriental ( Lesachtal ), avec les Avars et les Slaves occupant l’est de l’Autriche et l’actuelleBohême .

La Carantanie, sous la pression des Avars, devint un état vassal de la Bavière en 745 et fut plus tard incorporée dans l’ empire carolingien , d’abord comme margravat tribal sous les ducs slaves, et après l’échec de la rébellion de Ljudevit Posavski au début du IXe siècle, sous les Francs. -nommés nobles. Au cours des siècles suivants, les colons bavarois descendirent le Danube et remontèrent les Alpes, un processus par lequel l’Autriche allait devenir le pays majoritairement germanophone qu’elle est aujourd’hui. Seulement dans le sud de la Carinthie, la population slave a conservé sa langue et son identité jusqu’au début du XXe siècle, lorsqu’un processus d’assimilation a réduit son nombre à une petite minorité.

Moyen-âge

Haut Moyen Âge : duché de Bavière (VIIIe-Xe siècles)

Avar March dans l’est de la Bavière entre le Danube et la Drava Austrasie franque en 774 Territoires lombards et bavarois incorporés par Charlemagne en 788 Dépendances

Avar March dans l’est de la Bavière entre le Danube et la Drava Austrasie franque en 774 Territoires lombards et bavarois incorporés par Charlemagne en 788 Dépendances

Le Saint Empire romain germanique au 10ème siècle montrant les marches bavaroises, y compris la Carinthie.

Le Saint Empire romain germanique au 10ème siècle montrant les marches bavaroises, y compris la Carinthie.

Les relations bavaroises avec les Francs ont varié, obtenant une indépendance temporaire en 717 après JC, pour être subjuguées par Charles Martel. Enfin Charlemagne (empereur 800–814) déposa le dernier duc Agilolfing, Tassilo III , assumant le contrôle carolingien direct en 788 après JC, avec des rois bavarois non héréditaires. Charlemagne a ensuite conduit les Francs et les Bavarois contre les Avars de l’Est en 791, de sorte qu’en 803 ils se sont repliés à l’est des rivières Fischa et Leitha . [17] Ces conquêtes ont permis la mise en place d’un système de marches défensives (frontières militaires) du Danube à l’Adriatique. [19]Vers 800 après JC, Österreich, le “Royaume de l’Est”, avait été rattaché au Saint Empire romain germanique. [13]

Parmi celles-ci se trouvait une marche orientale, la marche Avar ( Awarenmark ), correspondant à peu près à l’actuelle Basse-Autriche , bordée par les rivières Enns , Raab et Drava , tandis qu’au sud se trouvait la marche de Carinthie . Les deux marches étaient collectivement appelées la Marcha orientalis (mars de l’Est), une préfecture du duché de Bavière. En 805, les Avars, avec la permission de Charlemagne, dirigés par les Avar Khagan, s’installèrent au sud-est de Vienne . [20]

Une nouvelle menace apparut en 862, les Hongrois , suivant le schéma de déplacement des territoires plus orientaux par des forces supérieures. En 896, les Hongrois étaient présents en grand nombre dans la plaine hongroise à partir de laquelle ils ont attaqué les domaines francs. Ils ont vaincu les Moraves et en 907 ont vaincu les Bavarois à la bataille de Presbourg et en 909 ils avaient dépassé les marches forçant les Francs et les Bavarois à retourner à la rivière Enns . [19]

La Bavière est devenue un margraviat sous Engeldeo (890–895) et a été rétablie en tant que duché sous Arnulf le Mauvais (907–937) qui l’a unie au duché de Carinthie , occupant la majeure partie des Alpes orientales. Cela s’est avéré de courte durée. Son fils Eberhard (937-938) s’est trouvé en conflit avec le roi allemand, Otto I (Otto le Grand) qui l’a déposé. Le duc suivant était Henri Ier (947–955), qui était le frère d’Otto. En 955, Otto réussit à repousser les Hongrois à la bataille de Lechfeld , entamant une lente reconquête des terres orientales, y compris l’ Istrie et la Carniole .

Sous le règne du fils d’Henri, Henri II (le Querelleur) (955–976), Otto devint le premier empereur romain germanique (962) et la Bavière devint un duché du Saint Empire romain germanique . Otton I rétablit la marche orientale, et fut remplacé par Otton II en 967, et se trouva en conflit avec Henri qu’il déposa, lui permettant de réorganiser les duchés de son empire.

Otto a considérablement réduit la Bavière, rétablissant la Carinthie au sud. À l’est, il établit une nouvelle marche orientale bavaroise , connue par la suite sous le nom d’Autriche, sous Léopold ( Luitpold ), comte de Babenberg en 976. Léopold Ier, également connu sous le nom de Léopold l’Illustre ( Luitpold der Erlauchte ) régna sur l’Autriche de 976 à 994.

Babenberg Autriche (976–1246)

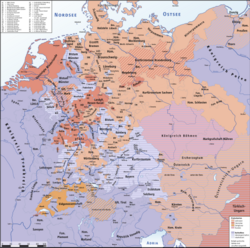

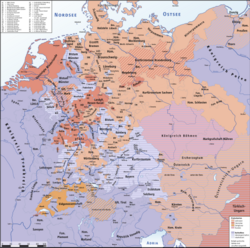

Duché de Bavière 976 après JC Margraviat (976-1156)

Duché de Bavière 976 après JC Margraviat (976-1156)

Ostarrîchi dans un document de l’époque d’ Otton III .

Ostarrîchi dans un document de l’époque d’ Otton III .

Le duché de Bavière (Bajovaria), le margravat d’Ostarrichi et le duché de Carantanie c. 1000 après JC.

Le duché de Bavière (Bajovaria), le margravat d’Ostarrichi et le duché de Carantanie c. 1000 après JC.

Les marches étaient supervisées par un come ou dux nommé par l’empereur. Ces titres sont généralement traduits par comte ou duc, mais ces termes véhiculaient des significations très différentes au Haut Moyen Âge , de sorte que les versions latines sont à préférer [ par qui ? ] . Dans les pays de langue lombarde , le titre a finalement été régularisé en margrave ( allemand : markgraf ) c’est-à-dire “comte de la marque”.

Le premier exemple enregistré du nom “Autriche” est apparu en 996, dans un document du roi Otton III écrit comme Ostarrîchi , faisant référence au territoire de la marche de Babenberg. De plus, pendant longtemps la forme Osterlant ( Ostland ou ‘Eastland’) était en usage, les habitants étant appelés Ostermann ou Osterfrau . Le nom latinisé Autriche appliqué à cette région apparaît dans les écrits du XIIe siècle à l’époque de Léopold III (1095-1136). (comparez l’ Austrasie comme le nom de la partie nord-est de l’Empire franc). Le terme Ostmarkn’est pas historiquement certain et semble être une traduction de marchia orientalis qui n’est apparue que beaucoup plus tard.

Les Babenberg ont poursuivi une politique de colonisation du pays, de défrichement des forêts et de fondation de villes et de monastères. Ils ont d’abord régné sur la Marche depuis Pöchlarn , puis depuis Melk , étendant continuellement le territoire vers l’est le long de la vallée du Danube , de sorte qu’en 1002, il atteignit Vienne . L’expansion vers l’est a finalement été stoppée par les Hongrois nouvellement christianisés en 1030, lorsque le roi Stephen (1001-1038) de Hongrie a vaincu l’empereur Conrad II (1024-1039) à Vienne.

Un territoire « central » avait finalement été établi. La terre contenait les vestiges de nombreuses civilisations antérieures, mais les Bavarois prédominaient, sauf dans la région du lac de Constance à l’ouest occupée par les Alamans ( Vorarlberg ). Des poches de la population celto-romane ( Walchen ou Welsche ) ont persisté, comme autour de Salzbourg , et des noms de lieux romains ont persisté, comme Juvavum (Salzbourg). De plus cette population se distinguait par le christianisme et par sa langue, un dialecte latin (le romanche ). Salzbourg était déjà un évêché (739) et en 798 un archevêché.

Bien que les Bavarois germaniques aient progressivement remplacé le romanche comme langue principale, ils ont adopté de nombreuses coutumes romaines et se sont de plus en plus christianisés. De même à l’est, l’allemand a remplacé la langue slave. Les voisins de la marche d’Autriche étaient le duché de Bavière à l’ouest, les royaumes de Bohême et de Pologne au nord, le royaume de Hongrie à l’est et le duché de Carinthie au sud. Dans ce cadre, l’Autriche, toujours soumise à la Bavière, était un acteur relativement modeste.

Les Margraves de Babenberg contrôlaient très peu l’Autriche moderne. Salzbourg, qui faisait historiquement partie de la Bavière, est devenue un territoire ecclésiastique, tandis que la Styrie faisait partie du duché de Carinthie. Les Babenberg avaient des propriétés relativement petites, non seulement Salzbourg mais les terres du diocèse de Passau étant entre les mains de l’église, et la noblesse contrôlant une grande partie du reste. Cependant, ils se sont lancés dans un programme de consolidation de leur base de pouvoir. L’une de ces méthodes consistait à employer des serviteurs sous contrat tels que la famille Kuenringern en tant que ministériels et à se voir confier des tâches militaires et administratives considérables. [21] Ils ont survécu en tant que dynastie grâce à la bonne fortune et à l’habileté à la politique de puissance, à cette époque dominée par le continuellutte entre l’empereur et la papauté .

Le chemin n’a pas toujours été facile. Le cinquième Margrave, Léopold II “Le Bel” ( Luitpold der Schöne ) (1075-1095) fut temporairement déposé par l’Empereur Henri IV (1084-1105) après s’être retrouvé du mauvais côté du conflit d’ investiture . Cependant, le fils de Léopold, Léopold III “Le Bon” ( Luitpold der Heilige ) (1095-1136) a soutenu le fils rebelle d’Henri, Henry V (1111-1125), a contribué à sa victoire et a été récompensé par la main de la sœur d’Henry, Agnes von Waiblingen en 1106, s’alliant ainsi à la famille impériale. Léopold se concentra alors sur la pacification de la noblesse. Son monastiquefondations, en particulier Klosterneuburg et Heiligenkreuz , ont conduit à sa canonisation posthume en 1458, et il est devenu le saint patron de l’ Autriche . [22]

Union avec la Bavière 1139

Léopold III a été remplacé par son fils, Léopold IV “Le Généreux” ( Luitpold der Freigiebige ) (1137-1141). Léopold a encore amélioré le statut de l’Autriche en devenant également duc de Bavière en 1139, car Léopold Ier. La Bavière elle-même avait été aux mains de la dynastie Welf (Guelph), qui s’opposait aux Hohenstaufen . Ce dernier monta sur le trône impérial en 1138 en la personne de Conrad III (1138-1152) ; le duc de Bavière, Henri le Fier , était lui-même candidat à la couronne impériale et contesta l’élection de Conrad, et fut par la suite privé du duché, qui fut donné à Léopold IV. À la mort de Léopold, ses terres ont été héritées par son frèreHenri II (Heinrich Jasomirgott) (1141-1177).

Entre-temps, Conrad avait été remplacé comme empereur par son neveu Frederick I Barbarossa (1155-1190), qui descendait à la fois des Welfs et des Hohenstauffens et cherchait à mettre fin aux conflits en Allemagne. À cette fin, il rendit la Bavière aux Welfs en 1156, mais en compensation éleva l’Autriche au rang de duché grâce à un instrument connu sous le nom de Privilegium Minus . Henri II devient ainsi duc d’Autriche en échange de la perte du titre de duc de Bavière.

Duché d’Autriche (1156-1246)

L’Autriche était maintenant un dominion indépendant au sein du Saint Empire romain germanique et Henry a déménagé sa résidence officielle à Vienne cette année-là.

Léopold le Vertueux et union avec la Styrie (1177-1194)

En 1186, le pacte de Georgenberg a légué le voisin méridional de l’Autriche, le duché de Styrie à l’Autriche à la mort du duc de Styrie sans enfant, Ottokar IV , survenue en 1192. La Styrie avait été découpée dans les marches du nord de la Carinthie , et seulement élevée à le statut de duché en 1180. Cependant, le territoire du duché de Styrie s’étendait bien au-delà de l’état actuel de la Styrie , y compris des parties de l’actuelle Slovénie ( Basse-Styrie ), ainsi que des parties de la Haute-Autriche (le Traungau, la région autour de Wels et Steyr ) et la Basse-Autriche (comté dePitten , quartiers actuels de Wiener Neustadt et Neunkirchen ).

Le deuxième duc d’Autriche, le fils d’Henri II, Léopold V le Vertueux ( Luitpold der Tugendhafte ) (1177-1194) devint duc de ces territoires combinés. Léopold est peut-être mieux connu pour son emprisonnement du roi britannique, Richard I après la troisième croisade (1189-1192), en 1192 à Dürnstein . L’argent de la rançon qu’il a reçu a aidé à financer nombre de ses projets.

À cette époque, les ducs de Babenberg sont devenus l’une des familles dirigeantes les plus influentes de la région, culminant sous le règne du petit-fils d’Henri Léopold VI le Glorieux ( Luitpold der Glorreiche ) (1198-1230), le quatrième duc. [18] sous lequel la culture du Haut Moyen Âge s’est épanouie, y compris l’introduction de l’art gothique .

Frédéric le Querelleur : Partage du territoire et fin de dynastie (1230-1246)

A la mort de Léopold, il fut remplacé par son fils Frédéric II le Querelleur ( Friedrich der Streitbare ) (1230-1246). En 1238, il divisa le pays en deux zones séparées par la rivière Enns . Cette partie au-dessus de l’Enns est devenue Ob(erhalb) der Enns (Au-dessus de l’Enns) ou ‘Haute-Autriche’ ( Oberösterreich ), bien que d’autres noms tels que supra anasum (d’un ancien nom latin pour la rivière), et Austria superior étaient également en utiliser. Ces terres en dessous de l’Enns ou unter der Enns sont devenues connues sous le nom de Basse-Autriche ( Niederösterreich). Le Traungau et le Steyr ont été intégrés à la Haute-Autriche plutôt qu’à la Styrie. Une autre des réalisations de Frederick était un brevet de protection pour les Juifs en 1244. [23]

Cependant, Frederick a été tué lors de la bataille de la rivière Leitha contre les Hongrois et n’a pas eu d’enfants survivants. Ainsi, la dynastie Babenburg s’est éteinte en 1246.

Interrègne (1246-1278)

Les royaumes d’ Ottokar II .

Les royaumes d’ Ottokar II .

S’ensuit un interrègne , une période de plusieurs décennies durant laquelle le statut du pays est contesté, et durant laquelle le duché de Frédéric II est victime d’un jeu de pouvoir prolongé entre forces rivales. Pendant ce temps, il y avait plusieurs prétendants au titre, dont Vladislas, margrave de Moravie, fils du roi Venceslas Ier de Bohême . Le roi Venceslas visait à acquérir le duché d’Autriche en organisant le mariage de Vladislas avec la dernière nièce du duc Gertrude , elle-même héritière et revendicatrice potentielle.

Selon le Privilegium Minus émis par l’empereur Frederick Barbarossa en 1156, les terres autrichiennes pouvaient être léguées par la lignée féminine. Vladislas reçut l’hommage de la noblesse autrichienne, mais mourut peu après, le 3 janvier 1247, avant de pouvoir prendre possession du duché. Vint ensuite Herman de Bade en 1248. Il revendiquait également en sollicitant la main de Gertrude mais n’avait pas le soutien de la noblesse. Herman mourut en 1250, et sa revendication fut reprise par son fils Frédéric , mais sa revendication fut contrecarrée par l’invasion bohémienne de l’Autriche.

Dans une tentative de mettre fin à la tourmente, un groupe de nobles autrichiens a invité le roi de Bohême , Ottokar II Přemysl, le frère de Vladislaus, à devenir le dirigeant de l’Autriche en 1251. Son père avait tenté d’envahir l’Autriche en 1250. Ottokar s’est alors allié à les Babenberg en épousant Margaret , fille de Léopold VI et donc candidate potentielle au trône, en 1252. Il soumit les nobles querelleurs et se fit souverain de la majeure partie de la région, y compris l’Autriche, la Styrie et la Corinthie.

Ottokar était un législateur et un bâtisseur. Parmi ses réalisations figurait la fondation du palais Hofburg à Vienne. Ottokar était en mesure d’établir un nouvel empire, étant donné la faiblesse du Saint Empire romain germanique à la mort de Frédéric II (1220-1250), en particulier après la fin de la dynastie Hohenstauffen en 1254 avec la mort de Conrad IV et l’ interrègne impérial qui s’ensuivit. (1254-1273). Ainsi Ottokar s’est présenté comme candidat au trône impérial, mais sans succès.

Persecution religieuse

Durant l’interrègne, l’Autriche fut le théâtre d’intenses persécutions des hérétiques par l’ Inquisition . Les premiers cas apparaissent en 1260 dans plus de quarante paroisses de la région sud du Danube entre le Salzkammergut et les bois de Vienne , et sont principalement dirigés contre les Vaudois .

Ascension des Habsbourg et mort d’Ottokar (1273-1278)

Ottokar a de nouveau contesté le trône impérial en 1273, étant presque seul à ce poste dans le collège électoral. Cette fois, il refusa d’accepter l’autorité du candidat retenu, Rodolphe de Habsbourg (empereur 1273-1291). En novembre 1274, la Diète impériale de Nuremberg décida que tous les domaines de la Couronne saisis depuis la mort de l’empereur Frédéric II (1250) devaient être restitués et que le roi Ottokar II devait répondre à la Diète pour ne pas avoir reconnu le nouvel empereur, Rudolf. Ottokar refusa soit de comparaître, soit de restaurer les duchés d’ Autriche , de Styrie et de Carinthie avec la Marche de Carniole , qu’il avait revendiquée par sa première épouse, une Babenberg .héritière, et dont il s’était emparé en les disputant avec un autre héritier Babenberg, le margrave Hermann VI de Bade .

Rudolph a réfuté la succession d’Ottokar au patrimoine Babenberg, déclarant que les provinces devaient revenir à la couronne impériale en raison du manque d’héritiers masculins (une position qui était cependant en conflit avec les dispositions du Privilegium Minus autrichien ). Le roi Ottokar fut placé sous le ban impérial ; et en juin 1276 la guerre fut déclarée contre lui, Rudolf assiégeant Vienne . Après avoir persuadé l’ancien allié d’Ottokar, le duc Henri XIII de Basse-Bavière de changer de camp, Rodolphe contraint le roi de Bohême à céder les quatre provinces au contrôle de l’administration impériale en novembre 1276.

Ottokar ayant renoncé à ses territoires en dehors des terres tchèques, Rodolphe le réinvestit dans le royaume de Bohême , fiancé sa plus jeune fille, Judith de Habsbourg , (au fils d’Ottokar, Wenceslas II ), et fit une entrée triomphale à Vienne. Ottokar, cependant, souleva des questions sur l’exécution du traité, fit alliance avec certains chefs Piast de Pologne et obtint le soutien de plusieurs princes allemands, dont encore une fois Henri XIII de Basse-Bavière. Pour rencontrer cette coalition, Rodolphe a formé une alliance avec le roi Ladislas IV de Hongrie et a donné des privilèges supplémentaires aux citoyens de Vienne.

Le 26 août 1278, les armées rivales se rencontrèrent lors de la bataille du Marchfeld , au nord-est de Vienne, où Ottokar fut vaincu et tué. Le margraviat de Moravie fut soumis et son gouvernement confié aux représentants de Rodolphe, laissant la veuve d’Ottokar, Kunigunda de Slavonie , aux commandes de la seule province entourant Prague, tandis que le jeune Venceslas II était de nouveau fiancé à Judith .

Rudolf put ainsi assumer le contrôle exclusif de l’Autriche, en tant que duc d’Autriche et de Styrie (1278-1282) qui resta sous la domination des Habsbourg pendant plus de six siècles, jusqu’en 1918.

L’établissement de la dynastie des Habsbourg : duché d’Autriche (1278-1453)

Rodolphe de Habsbourg , cathédrale de Spire où il fut enterré.

Rodolphe de Habsbourg , cathédrale de Spire où il fut enterré.

Ainsi l’Autriche et l’Empire passèrent sous une seule couronne des Habsbourg, et après quelques siècles (1438) le resteront presque continuellement (voir ci-dessous) jusqu’en 1806, date à laquelle l’empire fut dissous, évitant les conflits fréquents qui s’étaient produits auparavant.

Rodolphe Ier et primogéniture (1278-1358)

Rudolf I a passé plusieurs années à établir son autorité en Autriche, éprouvant quelques difficultés à établir sa famille comme successeurs à la règle de la province. Enfin l’hostilité des princes fut vaincue et il put léguer l’Autriche à ses deux fils. En décembre 1282, à la diète d’ Augsbourg , Rodolphe investit les duchés d’Autriche et de Styrie sur ses fils, Albert Ier (1282-1308) et Rodolphe II le Débonnaire(1282-1283) en tant que co-dirigeants “conjointement et solidairement”, et posèrent ainsi les fondations de la maison de Habsbourg. Rudolf a poursuivi ses campagnes en soumettant et en soumettant et en ajoutant à ses domaines, mourant en 1291, mais laissant une instabilité dynastique en Autriche, où fréquemment le duché d’Autriche était partagé entre les membres de la famille. Cependant Rudolf n’a pas réussi à assurer la succession au trône impérial des ducs d’Autriche et de Styrie.

Le duché conjoint n’a duré qu’un an jusqu’à ce que le traité de Rheinfelden ( Rheinfelder Hausordnung ) en 1283 établisse l’ ordre de succession des Habsbourg . Établissant la primogéniture, le duc Rodolphe II, alors âgé de onze ans, a dû renoncer à tous ses droits sur les trônes d’Autriche et de Styrie au profit de son frère aîné Albert I. Alors que Rodolphe était censé être indemnisé, cela ne s’est pas produit, mourant en 1290, et son fils Jean assassina par la suite son oncle Albert Ier en 1308. Pendant une brève période, Albert Ier partagea également les duchés avec Rodolphe III le Bon (1298-1307) et atteignit finalement le trône impérial en 1298.

À la mort d’Albert Ier, le duché mais pas l’empire passa à son fils, Frédéric le Bel (1308-1330), du moins pas avant 1314 lorsqu’il devint co-dirigeant de l’empire avec Louis IV . Frédéric dut également partager le duché avec son frère Léopold Ier le Glorieux (1308-1326). Un autre frère, Albert II le Sage (1330-1358) succéda à Frédéric.

Le modèle de corule a persisté, puisqu’Albert a dû partager le rôle avec un autre jeune frère Otto I le Joyeux (1330-1339), bien qu’il ait tenté sans succès d’établir les règles de succession dans la “règle de la maison albertinienne” ( Albertinische Hausordnung ) . À la mort d’Otto en 1339, ses deux fils, Frédéric II et Léopold II, le remplaçaient, faisant trois ducs d’Autriche simultanés de 1339 à 1344, lorsqu’ils moururent tous les deux à l’adolescence sans issue. La règle unique dans le duché d’Autriche est finalement revenue lorsque son fils, Rodolphe IV, lui succède en 1358.

Au XIVe siècle, les Habsbourg commencèrent à accumuler d’autres provinces à proximité du duché d’Autriche, qui était resté un petit territoire le long du Danube, et de la Styrie, qu’ils avaient acquise avec l’Autriche à Ottokar. En 1335, Albert II hérita du Duché de Carinthie et de la Marche de Carniole des dirigeants de l’époque, la Maison de Gorizia .

Rodolphe IV et le Privilegium Maius (1358-1365)

Rudolf IV le Fondateur (1358-1365) fut le premier à revendiquer le titre d’archiduc d’Autriche, par le Privilegium Maius de 1359, qui était en fait un faux et non reconnu en dehors de l’Autriche jusqu’en 1453. Cependant, cela l’aurait placé sur un sur un pied d’égalité avec les autres princes électeurs du Saint Empire romain germanique. Rudolph était l’un des dirigeants les plus actifs de son temps, initiant de nombreuses mesures et élevant l’importance de la ville de Vienne.

À cette époque, Vienne était ecclésiastiquement subordonnée au diocèse de Passau , que Rodolphe renversa en fondant la cathédrale Saint-Étienne et en nommant le prévôt archichancelier d’ Autriche. il a également fondé l’ Université de Vienne ( Alma Mater Rudolphina ). Il améliora l’économie et établit une monnaie stable, le Penny viennois ( Wiener Pfennig ). Quand il mourut en 1365, il était sans issue et la succession passa à ses frères conjointement selon les règles de la maison rudolfinienne ( Rudolfinische Hausordnung ).

En 1363, le comté de Tyrol est acquis par Rodolphe IV de Marguerite de Tyrol . Ainsi l’Autriche était maintenant un pays complexe dans les Alpes orientales, et ces terres sont souvent appelées les terres héréditaires des Habsbourg, ainsi que simplement l’Autriche, puisque les Habsbourg ont également commencé à accumuler des terres loin de leurs terres héréditaires. [24]

Albert III et Léopold III : Une maison divisée (1365-1457)

Presque tout le XVe siècle fut une confusion de conflits patrimoniaux et familiaux, ce qui affaiblit considérablement l’importance politique et économique des terres des Habsbourg. Ce n’est qu’en 1453 sous le règne de Frédéric V le Pacifique (1457-1493) que le pays (au moins les territoires centraux) sera enfin unifié à nouveau. Les frères de Rudolph IV, Albert III le Pigtail et Léopold III le Juste, se disputaient sans cesse et acceptèrent finalement de diviser le royaume lors du traité de Neuberg en 1379, qui devait entraîner de nouveaux schismes plus tard. Au total, cela a abouti à trois juridictions distinctes.

- Territoires de Basse-Autriche ou Niederösterreich ( Haute et Basse-Autriche )

- Albertinian Line – éteinte en 1457, passée aux Léopoldiens

- Territoires autrichiens intérieurs ou Innerösterreich ( Styrie , Carinthie , Carniole et le littoral autrichien d ‘ Istrie et de Trieste )

- Leopoldian Line puis Elder Ernestine Line 1406–1457, continuant comme Archiduché d’Autriche .

- Autres territoires autrichiens ou Vorderösterreich ( Tyrol , Vorarlberg et territoires souabes et alsaciens )

- Leopoldian Line puis Junior Tyrolean Line 1406–1490, repassé aux Léopoldiens

Lignée albertinienne (1379–1457)

En 1379, Albert III conserva l’Autriche proprement dite, régnant jusqu’en 1395. Il fut remplacé par son fils Albert IV (1395–1404) et son petit-fils Albert V (1404–1439) qui regagna le trône impérial pour les Habsbourg et grâce à ses acquisitions territoriales, il fut mis à devenu l’un des dirigeants les plus puissants d’Europe s’il n’était pas mort quand il l’a fait, ne laissant qu’un héritier posthume , né quatre mois plus tard ( Ladislas le Posthume 1440–1457). Au lieu de cela, c’était le tuteur et successeur de Ladislaus, le Léopoldien Frédéric Vles Pacifiques (1457-1493) qui en bénéficièrent. La lignée albertinienne s’étant éteinte, le titre revenait désormais aux Léopoldiens. Frederick était tellement conscient du potentiel d’être le tuteur du jeune Ladislaus qu’il a refusé de le laisser gouverner de manière indépendante après avoir atteint la majorité (12 ans en Autriche à l’époque) [25] et a dû être contraint de le libérer par les États autrichiens (Ligue de Mailberg 1452).

Lignée léopoldienne (1379–1490)

Léopold III a pris les territoires restants, régnant jusqu’en 1386. Il a été succédé par deux de ses fils conjointement, Guillaume le Courtois (1386–1406) et Léopold IV le Gros (1386–1411). En 1402, une autre scission du duché se produisit, puisque Léopold III avait eu quatre fils et que ni Léopold IV ni Guillaume n’avaient d’héritiers. Les frères restants ont ensuite divisé le territoire.

Ernest le fer (1402–1424) a pris l’Autriche intérieure, tandis que Frédéric IV des poches vides (1402–1439) a pris l’Autriche plus loin. Une fois que William est mort en 1406, cela a pris effet formellement avec deux lignes ducales distinctes, respectivement la ligne Elder Ernestine et la ligne Junior Tyrolean .

Ligne Ernestine (Autriche intérieure 1406–1457)

Frédéric V (1415-1493) par Hans Burgkmair , ch. 1500 ( Kunsthistorisches Museum , Vienne ). Duc 1424, Roi 1440, Empereur 1452, Archiduc 1457.

Frédéric V (1415-1493) par Hans Burgkmair , ch. 1500 ( Kunsthistorisches Museum , Vienne ). Duc 1424, Roi 1440, Empereur 1452, Archiduc 1457.

La lignée Ernestine se composait d’Ernest et d’un règne conjoint de deux de ses fils à sa mort en 1424, Albert VI le Prodigue (1457–1463) et Frédéric V le Paisible (1457–1493). Eux aussi se querellèrent et à leur tour divisèrent ce qui était devenu à la fois la Basse et l’intérieure de l’Autriche à la mort de Ladislas en 1457 et l’extinction des Albertins. Albert s’empare de la Haute-Autriche en 1458, régnant depuis Linz , mais en 1462, il procède au siège de son frère aîné dans le palais Hofburg à Vienne, s’emparant également de la Basse-Autriche. Cependant, depuis qu’il est mort sans enfant l’année suivante (1463), ses biens sont automatiquement revenus à son frère, et Frédéric contrôlait désormais toutes les possessions d’Albertin et d’Ernestine.

La carrière politique de Frédéric avait avancé de manière majeure, puisqu’il hérita du duché d’Autriche intérieure en 1424. De duc, il devint roi d’Allemagne sous le nom de Frédéric IV en 1440 et empereur du Saint Empire romain germanique sous le nom de Frédéric III (1452–1493).

Lignée tyrolienne (Autre Autriche) 1406–1490

La lignée tyrolienne se composait de Frédéric IV et de son fils, Sigismond le Riche (1439–1490). Frederick a déplacé sa cour à Innsbruck mais a perdu certains de ses biens au profit de la Suisse. Sigismond qui lui succéda vendit certaines de ses terres à Charles le Téméraire en 1469 et fut élevé au rang d’archiduc par l’empereur Frédéric III en 1477. Il mourut sans enfant, mais en 1490, il abdiqua face à l’impopularité et l’Autriche plus loin revint à l’archiduc d’alors. , Maximilien Ier le Dernier Chevalier (1490-1493), fils de Frédéric V qui contrôlait désormais efficacement tout le territoire des Habsbourg pour la première fois depuis 1365.

Persecution religieuse

1997 Monument à ceux brûlés par Petrus Zwicker à Steyr en 1397.

1997 Monument à ceux brûlés par Petrus Zwicker à Steyr en 1397.

L’inquisition était également active sous les Habsbourg, en particulier entre 1311 et 1315 lorsque des inquisitions ont eu lieu à Steyr , Krems , St. Pölten et Vienne. L’inquisiteur, Petrus Zwicker , a mené de graves persécutions à Steyr, Enns , Hartberg , Sopron et Vienne entre 1391 et 1402. En 1397, quelque 80 à 100 Vaudois ont été brûlés à Steyr seulement, dont on se souvient maintenant dans un monument de 1997.

Duché et Royaume

Pendant le duché des Habsbourg, il y avait 13 ducs consécutifs, dont quatre ont également été couronnés roi d’Allemagne , Rodolphe Ier , Albert Ier , Frédéric le Bel et Albert V (Albert II comme roi d’Allemagne), bien qu’aucun n’ait été reconnu comme Saint-Empire romain germanique . Empereurs par le Pape .

Lorsque le duc Albert V (1404-1439) fut élu empereur en 1438 (en tant qu’Albert II), en tant que successeur de son beau-père, Sigismund von Luxemburg (1433-1437), la couronne impériale revint une fois de plus aux Habsbourg. Bien qu’Albert lui-même n’ait régné qu’un an (1438-1439), à partir de ce moment-là, chaque empereur était un Habsbourg (à une seule exception près : Charles VII 1742-1745), et les dirigeants autrichiens étaient également les empereurs romains jusqu’à sa dissolution en 1806. .

Archiduché d’Autriche : devenir une grande puissance (1453-1564)

Frédéric V (1453-1493) : Élévation du duché

Frédéric V (Duc 1424 Archiduc 1453, mort en 1493) le Pacifique ( Empereur Frédéric III 1452-–1493) confirma le Privilegium Maius de Rodolphe IV en 1453, et ainsi l’Autriche devint un archiduché officiel du Saint Empire romain germanique, la prochaine étape dans son ascendant en Europe, et Ladislas le Posthume (1440–1457) le premier archiduc officiel pendant une brève période, mourant peu de temps après. Le document était un faux, prétendument écrit par l’empereur Frédéric Iet “redécouvert”. Frederick avait un motif clair pour cela. C’était un Habsbourg, il était duc d’Autriche intérieure en plus d’être empereur et, jusqu’à l’année précédente, il avait été tuteur du jeune duc de Basse-Autriche, Ladislas. Il se tenait également pour hériter du titre de Ladislaus, et l’a fait lorsque Ladislaus mourut quatre ans plus tard, devenant le deuxième archiduc.

Les archiducs autrichiens avaient désormais le même statut que les autres princes électeurs qui choisissaient les empereurs. La gouvernance autrichienne devait désormais reposer sur la primogéniture et l’indivisibilité. Plus tard, l’Autriche devait devenir officiellement connue sous le nom de ” Erzherzogtum Österreich ob und unter der Enns ” (L’archiduché d’Autriche au-dessus et au-dessous de l’Enns). En 1861, elle fut à nouveau divisée en Haute et Basse Autriche .

Le pouvoir relatif de l’empereur dans la monarchie n’était pas grand, car de nombreuses autres dynasties aristocratiques poursuivaient leur propre pouvoir politique à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur de la monarchie. Cependant Frederick, bien que terne, a poursuivi une règle dure et efficace. Il a poursuivi le pouvoir par des alliances dynastiques. En 1477 , Maximilien (archiduc et empereur 1493-1519), fils unique de Frédéric , épousa Marie , duchesse de Bourgogne , acquérant ainsi la plupart des Pays-Bas .pour la famille. L’importance stratégique de cette alliance était que la Bourgogne, qui se trouvait à la frontière occidentale de l’empire, manifestait des tendances expansionnistes et était à l’époque l’un des États-nations d’Europe occidentale les plus riches et les plus puissants, avec des territoires s’étendant du sud de la France à la mer du Nord .

L’alliance a été réalisée à un coût non négligeable, puisque la France, qui revendiquait également la Bourgogne, a contesté cette acquisition, et Maximilien a dû défendre les territoires de sa nouvelle épouse contre Louis XI , le faisant finalement à la mort de Marie en 1482 à la paix d’Arras . Les relations avec la France restaient difficiles, Louis XI étant vaincu à la bataille de Guinegate en 1479. Les affaires avec la France ne furent conclues qu’en 1493 au traité de Senlis après que Maximilien fut devenu empereur.

Ceci et les alliances dynastiques ultérieures de Maximilien ont donné lieu au dicton: [26]

Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube ,

Nam quae Mars aliis, dat tibi regna Venus [c]

qui devint une devise de la dynastie. Le règne de Frédéric a été déterminant dans l’histoire autrichienne. Il a uni les terres centrales en survivant simplement au reste de sa famille. À partir de 1439, date à laquelle Albert V mourut et que les responsabilités des deux territoires centraux incombèrent à Frédéric, il consolida systématiquement sa base de pouvoir. L’année suivante (1440), il marcha sur Rome en tant que roi des Romains avec son pupille, Ladislas, le dernier duc Albertin, et lorsqu’il fut couronné à Rome en 1452, il fut non seulement le premier Habsbourg mais aussi le dernier roi allemand à être couronné. à Rome par le Pape. [27]

La dynastie était maintenant en route pour devenir une puissance mondiale. Le concept de pietas austriacae (le devoir divin de régner était né avec Rodolphe Ier, mais a été reformulé par Frédéric comme AEIOU , Alles Erdreich ist Österreich untertan ou Austriae est imperare orbi universo (le destin de l’Autriche est de gouverner le monde), qui en est venu à symboliser Puissance autrichienne [27] Cependant, tous les événements ne se sont pas déroulés sans heurts pour Frédéric. La guerre austro-hongroise (1477-1488) a conduit le roi hongrois Matthias Corvinus à s’installer à Vienne en 1485 .jusqu’à sa mort en 1490. La Hongrie occupa toute l’Autriche orientale. Frederick s’est donc retrouvé avec une cour itinérante, principalement dans la capitale de la Haute-Autriche, Linz .

Maximilien Ier (1493-1519) : Réunification

Maximilien I par Albrecht Dürer 1519

Maximilien I par Albrecht Dürer 1519

Maximilien I partagea le pouvoir avec son père pendant la dernière année du règne de Frédéric, étant élu roi des Romains en 1486. En acquérant les terres de la lignée tyrolienne des Habsbourg en 1490, il réunit finalement toutes les terres autrichiennes, divisées depuis 1379. Il devait également régler le problème hongrois lorsque Mathias I mourut en 1490. Maximilien reconquit les parties perdues de l’Autriche et établit la paix avec le successeur de Mathias, Vladislas II , lors de la paix de Pressbourg en 1491. Cependant, le modèle dynastique de division et d’unification serait celui qui ne cessait de se répéter au fil du temps. Avec des frontières instables, Maximilian a trouvé Innsbruck dans le Tyrolun endroit plus sûr pour une capitale, entre ses terres bourguignonnes et autrichiennes, bien qu’il ait rarement été très longtemps dans n’importe quel endroit, étant parfaitement conscient de la façon dont son père avait été assiégé à plusieurs reprises à Vienne.

Maximilien a élevé l’art de l’alliance dynastique à un nouveau sommet et s’est mis à créer systématiquement une tradition dynastique, bien qu’à travers un révisionnisme considérable. Sa femme Mary, devait mourir en 1482, seulement cinq ans après leur mariage. Il épousa ensuite Anne, duchesse de Bretagne (par procuration) en 1490, un geste qui aurait amené la Bretagne , alors indépendante, dans le giron des Habsbourg, ce qui était considéré comme provocateur pour la monarchie française. Charles VIII de France avait d’autres idées et annexa la Bretagne et épousa Anne, une situation encore compliquée par le fait qu’il était déjà fiancé à la fille de Maximilien, Margaret , duchesse de Savoie . Fils de Maximilien, Philippe le Bel(1478-1506) épousa Jeanne , héritière de Castille et d’ Aragon en 1496, et acquit ainsi l’Espagne et ses appendices italiens ( Naples , Royaume de Sicile et Sardaigne ), africains et du Nouveau Monde pour les Habsbourg.

Cependant , le noyau de Tu felix Austria était peut-être plus romantique que strictement réaliste, puisque Maximilien ne tardait pas à faire la guerre quand cela convenait à son objectif. Après avoir réglé les affaires avec la France en 1493, il fut bientôt impliqué dans les longues guerres d’Italie contre la France (1494-1559). Aux guerres contre les Français s’ajoutent les guerres pour l’ indépendance de la Suisse . La guerre souabe de 1499 marqua la dernière phase de cette lutte contre les Habsbourg. Après la défaite à la bataille de Dornach en 1499, l’Autriche a été forcée de reconnaître l’ indépendance de la Suisse lors du traité de Bâle en 1499, un processus qui a finalement été officialisé par la paix de Westphalie .en 1648. C’était important car les Habsbourg étaient originaires de Suisse , leur maison ancestrale étant le château des Habsbourg .

En politique intérieure, Maximilien lança une série de réformes lors de la Diète de Worms de 1495 , au cours de laquelle la Cour de chambre impériale ( Reichskammergericht ) fut lancée en tant que plus haute juridiction. Une autre nouvelle institution de 1495 était le Reichsregiment ou gouvernement impérial, réuni à Nuremberg . Cet exercice préliminaire de démocratie a échoué et a été dissous en 1502. Les tentatives de création d’un État unifié n’ont pas été très réussies, mais ont plutôt refait surface l’idée des trois divisions de l’Autriche qui existaient avant l’unification de Frédéric et Maximilien. [28]

À court de fonds pour ses divers projets, il s’est fortement appuyé sur des familles bancaires telles que les Fugger , et ce sont ces banquiers qui ont soudoyé les princes électeurs pour choisir le petit-fils de Maximilien, Charles, comme son successeur. Une tradition qu’il a supprimée était la coutume séculaire selon laquelle l’empereur romain germanique devait être couronné par le pape à Rome. Incapable d’atteindre Rome, en raison de l’hostilité vénitienne, en 1508, Maximilien, avec l’assentiment du pape Jules II , prend le titre d’ Erwählter Römischer Kaiser (“Empereur romain élu”). Ainsi son père Frédéric fut le dernier empereur à être couronné par le pape à Rome.

Charles Ier et Ferdinand Ier (1519-1564)

Charles Ier , attrib. Lambert Sustris 1548, Musée du Prado , Madrid , Espagne

Charles Ier , attrib. Lambert Sustris 1548, Musée du Prado , Madrid , Espagne

Depuis que Philippe le Bel (1478-1506) est mort avant son père, Maximilien, la succession passa au fils de Philippe, Charles Ier (1519-1521) qui devint l’empereur Charles V, à la mort de Maximilien en 1519. Il régna comme empereur de 1519 à 1556, alors qu’il était en mauvaise santé, il abdiqua et mourut en 1558. Bien que couronné par le pape Clément VII à Bologne en 1530 (Charles avait limogé Rome en 1527), il fut le dernier empereur à être couronné par un pape. Bien qu’il soit finalement tombé en deçà de sa vision de la monarchie universelle, Charles Ier est toujours considéré comme le plus puissant de tous les Habsbourg. Son chancelier, Mercurino Gattinara a fait remarquer en 1519 qu’il était “sur la voie de la monarchie universelle … unir toute la chrétienté sous un même sceptre”[29] le rapprochant de la vision de Frédéric V d’AEIOU, et la devise de Charles Plus ultra (encore plus loin) suggérait que c’était son ambition. [30]

Ayant hérité des biens de son père en 1506, il était déjà un souverain puissant avec de vastes domaines. A la mort de Maximilien, ces domaines devinrent vastes. Il était maintenant le dirigeant de trois des principales dynasties européennes – la maison des Habsbourg de la monarchie des Habsbourg ; la Maison des Valois-Bourgogne des Pays-Bas bourguignons ; et la Maison de Trastámara des Couronnes de Castille et Aragon . Cela l’a fait régner sur de vastes terres en Europe centrale, occidentale et méridionale; et les colonies espagnoles des Amériques et d’Asie. En tant que premier roi à régner sur la Castille, León, et Aragon simultanément à part entière, il devient le premier roi d’Espagne . [31] Son empire s’étendait sur près de quatre millions de kilomètres carrés à travers l’Europe, l’Extrême-Orient et les Amériques. [32]

Un certain nombre de défis se dressaient sur le chemin de Charles et allaient façonner l’histoire de l’Autriche pendant longtemps. C’étaient la France, l’apparition de l’ Empire ottoman à l’Est, et Martin Luther (voir ci-dessous).

Suivant la tradition dynastique, les territoires héréditaires des Habsbourg ont été séparés de cet énorme empire lors de la diète de Worms en 1521, lorsque Charles Ier les a laissés à la régence de son jeune frère, Ferdinand I (1521-1564), bien qu’il ait ensuite continué à ajouter aux territoires des Habsbourg. Depuis que Charles a laissé son Empire espagnol à son fils Philippe II d’Espagne , les territoires espagnols se sont définitivement éloignés des domaines du nord des Habsbourg, bien qu’ils soient restés alliés pendant plusieurs siècles.

Au moment où Ferdinand a également hérité du titre d’empereur du Saint Empire romain germanique de son frère en 1558, les Habsbourg avaient effectivement transformé un titre électif en un titre héréditaire de facto . Ferdinand a poursuivi la tradition des mariages dynastiques en épousant Anne de Bohême et de Hongrie en 1521, ajoutant effectivement ces deux royaumes aux domaines des Habsbourg, ainsi que les territoires adjacents de Moravie , de Silésie et de Lusace . Cela a pris effet lorsque le frère d’Anne, Louis II, roi de Hongrie et de Bohême (et donc de la dynastie Jagellon ) est mort sans héritier à la bataille de Mohács en 1526 contre Soliman le Magnifique .et les Ottomans. Cependant, en 1538, le Royaume de Hongrie était divisé en trois parties :

- Le Royaume de Hongrie ( Hongrie royale ) (aujourd’hui Burgenland , certaines parties de la Croatie , principalement la Slovaquie et certaines parties de la Hongrie actuelle ) a reconnu les Habsbourg comme rois.

- Hongrie ottomane (le centre du pays).

- Royaume de Hongrie orientale , plus tard la Principauté de Transylvanie sous les contre-rois des Habsbourg, mais aussi sous la protection ottomane.

L’élection de Ferdinand à l’empereur en 1558 a de nouveau réuni les terres autrichiennes. Il avait dû faire face à des révoltes dans ses propres terres, à des troubles religieux, à des incursions ottomanes et même à la lutte pour le trône hongrois de John Sigismund Zápolya . Ses terres n’étaient en aucun cas les plus riches des terres des Habsbourg, mais il réussit à rétablir l’ordre intérieur et à tenir les Turcs à distance, tout en élargissant ses frontières et en créant une administration centrale.

Lorsque Ferdinand mourut en 1564, les terres furent à nouveau partagées entre ses trois fils, une disposition qu’il avait prise en 1554. [33]

L’Autriche dans la Réforme et la Contre-Réforme (1517-1564)

Une grande partie de l’est de l’Autriche a adopté le luthéranisme jusqu’à ce que les efforts de contre-réforme le modifient à la fin du XVIe siècle.

Une grande partie de l’est de l’Autriche a adopté le luthéranisme jusqu’à ce que les efforts de contre-réforme le modifient à la fin du XVIe siècle.

Archiduc Ferdinand Ier, 1521-1564 Martin Luther et la Réforme protestante (1517-1545)

Archiduc Ferdinand Ier, 1521-1564 Martin Luther et la Réforme protestante (1517-1545)

Lorsque Martin Luther a affiché ses quatre-vingt-quinze thèses à la porte de l’ église du château de Wittenberg en 1517, il a contesté la base même du Saint Empire romain germanique, le christianisme catholique, et donc l’hégémonie des Habsbourg. Après que l’ empereur Charles Quint eut interrogé et condamné Luther à la Diète de Worms en 1521 , le luthéranisme et la Réforme protestante se répandirent rapidement dans les territoires des Habsbourg. Temporairement libéré de la guerre avec la France par le traité de Cambrai de 1529 et la dénonciation de l’interdiction de Luther par les princes protestants à Spire cette année-là, l’Empereur revint ensuite sur la question à laRégime d’Augsbourg en 1530, date à laquelle il était bien établi.

Avec la menace ottomane croissante (voir ci-dessous), il devait s’assurer qu’il ne faisait pas face à un schisme majeur au sein du christianisme. Il réfute la position luthérienne ( Confession d’ Augsbourg ) ( Confessio Augustana ) avec la Confutatio Augustana , et fait élire Ferdinand roi des Romains le 5 janvier 1531, assurant sa succession comme monarque catholique. En réponse, les princes et domaines protestants formèrent la Ligue Schmalkaldic en février 1531 avec le soutien français. D’autres avancées turques en 1532 (qui l’ont obligé à demander l’aide des protestants) et d’autres guerres ont empêché l’empereur de prendre d’autres mesures sur ce front jusqu’en 1547, lorsque les troupes impériales ont vaincu la Ligue à la bataille de Mühlberg., lui permettant d’imposer une fois de plus le catholicisme.

En 1541, l’appel de Ferdinand aux États généraux pour obtenir de l’aide contre les Turcs fut accueilli par une demande de tolérance religieuse. Le triomphe de 1547 s’est avéré être de courte durée avec les forces françaises et protestantes défiant à nouveau l’empereur en 1552 aboutissant à la paix d’Augsbourg en 1555. Épuisé, Charles a commencé à se retirer de la politique et à passer les rênes. Le protestantisme s’était montré trop solidement enraciné pour pouvoir être déraciné.

L’Autriche et les autres provinces héréditaires des Habsbourg (ainsi que la Hongrie et la Bohême) ont été très touchées par la Réforme, mais à l’exception du Tyrol , les terres autrichiennes ont exclu le protestantisme. Bien que les dirigeants des Habsbourg eux-mêmes soient restés catholiques, les provinces non autrichiennes se sont largement converties au luthéranisme, ce que Ferdinand Ier a largement toléré.

Contre-Réforme (1545-1563)

La réponse catholique à la Réforme protestante a été conservatrice, mais a répondu aux problèmes soulevés par Luther. En 1545, le long Concile de Trente commença son travail de réforme et de Contre-Réforme aux confins des domaines des Habsbourg. Le Conseil a continué par intermittence jusqu’en 1563. Ferdinand et les Habsbourg autrichiens étaient beaucoup plus tolérants que leurs frères espagnols, et le processus a commencé à Trente . Cependant, ses tentatives de réconciliation au Concile en 1562 ont été rejetées, et bien qu’une contre-offensive catholique ait existé dans les terres des Habsbourg à partir des années 1550, elle était basée sur la persuasion, un processus dans lequel les jésuites et Peter Canisiusa pris les devants. Ferdinand a profondément regretté l’échec de concilier les différences religieuses avant sa mort (1564). [34]

L’arrivée des Ottomans (1526-1562)

Lorsque Ferdinand I s’est marié avec la dynastie hongroise en 1521, l’Autriche a rencontré pour la première fois l’ expansion ottomane vers l’ouest qui était entrée en conflit avec la Hongrie dans les années 1370. Les choses ont pris fin lorsque le frère de sa femme Anne , le jeune roi Louis , a été tué en combattant les Turcs sous Soliman le Magnifique à la bataille de Mohács en 1526, le titre passant à Ferdinand. La veuve de Louis, Mary , s’enfuit pour demander la protection de Ferdinand.

Les Turcs se retirèrent d’abord suite à cette victoire, réapparaissant en 1528 avançant sur Vienne et l’ assiégeant l’année suivante. Ils se retirèrent cet hiver-là jusqu’en 1532, date à laquelle leur avance fut stoppée par Charles Quint , bien qu’ils contrôlaient une grande partie de la Hongrie. Ferdinand a ensuite été contraint de reconnaître John Zápolya Ferdinand et les Turcs ont continué à faire la guerre entre 1537 et une trêve temporaire en 1547 lorsque la Hongrie a été partagée. Cependant, les hostilités se sont poursuivies presque immédiatement jusqu’au traité de Constantinople de 1562 qui a confirmé les frontières de 1547. La menace ottomane devait se poursuivre pendant 200 ans.

Redécoupage des terres des Habsbourg (1564-1620)

Ferdinand Ier eut trois fils qui survécurent jusqu’à l’âge adulte, et il suivit la tradition potentiellement désastreuse des Habsbourg de se partager ses terres à sa mort en 1564. Cela affaiblit considérablement l’Autriche, notamment face à l’expansion ottomane. Ce n’est que sous le règne de Ferdinand III (archiduc 1590-1637) qu’ils furent à nouveau réunis en 1620, quoique brièvement jusqu’en 1623. Ce n’est qu’en 1665, sous Léopold Ier , que les terres autrichiennes furent définitivement unies.

Au cours des 60 années suivantes, la monarchie des Habsbourg a été divisée en trois juridictions :

- “Basse-Autriche” – Les duchés autrichiens, la Bohême sont passés à la lignée de Charles II en 1619.

- Maximilien II (1564-1576); Rodolphe V (1576-1608); Mathias (1608-1619)

- “Haute-Autriche” – Tyrol et autre Autriche , passa à la lignée de Maximilien II 1595 (sous l’administration de Maximilien III , 1595–1618).

- Ferdinand II (1564-1595)

- “Autriche intérieure”

- Charles II (1564-1590); Ferdinand III (1590-1637)

En tant que fils aîné, Maximilien II et ses fils ont obtenu les territoires «essentiels» de la Basse et de la Haute-Autriche. Ferdinand II mourant sans issue vivante, ses territoires sont revenus aux territoires centraux à sa mort en 1595, puis sous Rudolf V (1576–1608), le fils de Maximilien II.

Maximilien II a été remplacé par trois de ses fils dont aucun n’a laissé d’héritiers vivants, de sorte que la lignée s’est éteinte en 1619 lors de l’abdication d’ Albert VII (1619-1619). Ainsi, le fils de Charles II, Ferdinand III, hérita de toutes les terres des Habsbourg. Cependant, il perdit rapidement la Bohême qui se rebella en 1619 et fut brièvement (1619-1620) sous le règne de Frédéric Ier . Ainsi, toutes les terres revinrent sous un même souverain en 1620 lorsque Ferdinand III envahit la Bohême, battant Frédéric Ier.

Bien qu’il s’agisse techniquement d’un poste électif, le titre d’empereur romain germanique a été transmis par Maximilien II et les deux fils (Rudolf V et Mathias) qui lui ont succédé. Albert VII ne fut archiduc que quelques mois avant d’abdiquer au profit de Ferdinand III, qui devint également empereur.

“Basse-Autriche”

Rudolf V (archiduc, empereur Rudolf II 1576–1612), fils aîné de Maximilien, a déplacé sa capitale de Vienne vers le lieu plus sûr de Prague, compte tenu de la menace ottomane. Il était connu comme un grand mécène des arts et des sciences mais un mauvais gouverneur. Parmi ses legs figure la couronne impériale des Habsbourg . Il a préféré répartir ses responsabilités entre ses nombreux frères (dont six ont vécu jusqu’à l’âge adulte), ce qui a conduit à une grande hétérogénéité des politiques à travers les terres. Parmi ces délégations figurait son jeune frère Mathias, gouverneur d’Autriche en 1593.