Guerre Iran-Irak

La guerre Iran-Irak [c] ( persan : جنگ ایران و عراق ; arabe : الحرب الإيرانية العراقية ) était un conflit armé prolongé qui a commencé le 22 septembre 1980 avec une invasion à grande échelle de l’Iran par l’ Irak voisin . La guerre a duré près de huit ans et s’est terminée dans une impasse le 20 août 1988, lorsque l’Iran a accepté la résolution 598 du Conseil de sécurité des Nations unies . La principale justification de l’invasion de l’Irak était de paralyser l’Iran et d’empêcher Ruhollah Khomeiny d’ exporter la révolution iranienne de 1979mouvement vers l’Irak à majorité chiite et exploiter en interne les tensions religieuses qui menaceraient les dirigeants baasistes dominés par les sunnites et dirigés par Saddam Hussein . L’Irak souhaitait également remplacer l’Iran en tant qu’État dominant dans le golfe Persique , ce qui, avant la révolution iranienne, n’était pas considéré comme un objectif réalisable par les dirigeants irakiens en raison de la puissance économique et militaire colossale de l’ Iran pré-révolutionnaire ainsi que de ses alliances étroites avec les États-Unis , une superpuissance , et Israël , un acteur majeur au Moyen-Orient. La guerre faisait suite à une longue histoire de différends frontaliers bilatéraux entre les deux États, à la suite desquels l’Irak prévoyait de reprendre la rive orientale du Chatt al-Arab cédé en 1975. L’Irak a soutenu les séparatistes arabes dans le territoire riche en pétrole de Le Khouzistan à la recherche d’un État arabe connu sous le nom d'”Arabistan” qui avait déclenché une insurrection en 1979 avec le soutien de l’Irak. L’Irak a cherché à prendre le contrôle du Khouzistan et à le séparer de l’Iran. [72] Saddam Hussein a déclaré publiquement en novembre 1980 que l’Irak ne cherchait pas l’annexion du Khuzestan à l’Irak ; [73] on pense plutôt que l’Irak a cherché à établir une suzeraineté sur le territoire.[74]

| Guerre Iran-Irak | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Une partie des conflits du golfe Persique | ||||||||

En haut à gauche en bas à droite :

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| belligérants | ||||||||

|

Supporté par:

|

Supporté par:

|

|||||||

| Commandants et chefs | ||||||||

|

Autres :

|

Autres:

|

|||||||

| Unités impliquées | ||||||||

| voir ordre de bataille | voir ordre de bataille | |||||||

| Force | ||||||||

|

Début de la guerre : [45] Suite:

|

Début de guerre : [45] Suite:

|

|||||||

| Victimes et pertes | ||||||||

|

Morts militaires : Suite:

|

Morts militaires : Suite:

|

|||||||

| Civils morts : 100 000+ [note 4] |

Alors que les dirigeants irakiens avaient espéré profiter du chaos post-révolutionnaire de l’Iran et s’attendaient à une victoire décisive face à un Iran gravement affaibli, l’ armée irakienne n’a fait de progrès que pendant trois mois et, en décembre 1980, l’invasion irakienne de l’Iran avait au point mort. Alors que de violents combats ont éclaté entre les deux parties, l’ armée iranienne a commencé à prendre de l’ampleur contre les Irakiens et a regagné la quasi-totalité de son territoire perdu en juin 1982. Après avoir repoussé les forces irakiennes jusqu’aux frontières d’avant-guerre, l’Iran a envahi l’Irak et est allé à l’offensive pour les cinq prochaines années [75]jusqu’à ce que ce dernier reprenne l’initiative à la mi-1988 et lance une série de contre-offensives majeures qui aboutiront finalement à la conclusion de la guerre dans l’impasse. [76] [67] Il y avait un certain nombre de forces par procuration opérant pour les deux pays, notamment les Moudjahidine du peuple d’Iran , qui s’étaient rangés du côté de l’Irak, et les milices kurdes irakiennes du PDK et de l’ UPK , qui s’étaient rangées du côté de l’Iran. Les États-Unis , le Royaume-Uni , l’Union soviétique , la France et de nombreux pays arabesfourni une abondance de soutien financier, politique et logistique à l’Iraq. Alors que l’Iran était relativement isolé dans une large mesure, il a reçu diverses formes de soutien, ses principales sources d’aide étant la Syrie , la Libye , la Chine , la Corée du Nord , Israël , le Pakistan et le Yémen du Sud .

Les huit années d’épuisement de la guerre, la dévastation économique, la baisse du moral, l’impasse militaire, l’inaction de la communauté internationale face à l’ utilisation d’armes de destruction massive par les forces irakiennes contre des civils iraniens ainsi que l’augmentation des tensions militaires américano-iraniennes ont tous abouti à l’acceptation de l’Iran. d’un cessez-le-feu négocié par les Nations Unies .

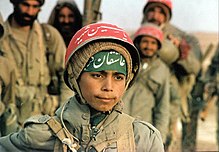

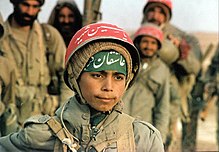

Le conflit a été comparé à la Première Guerre mondiale en termes de tactiques utilisées, y compris une guerre de tranchées à grande échelle avec des barbelés tendus sur des lignes défensives fortifiées, des postes de mitrailleuses habitées, des charges à la baïonnette , des attaques par vagues humaines iraniennes , l’utilisation intensive d’ armes chimiques par l’Irak et des attaques délibérées contre des cibles civiles. Une caractéristique notable de la guerre était la glorification sanctionnée par l’État du martyre des enfants iraniens, qui s’était développée dans les années précédant la révolution. Les discours sur le martyre formulés dans le discours islamique chiite iraniencontexte a conduit à la tactique des “attaques par vague humaine” et a donc eu un impact durable sur la dynamique de la guerre. [77]

Au total, environ 500 000 personnes ont été tuées pendant la guerre (l’Iran supportant la plus grande part des victimes), sans compter les dizaines de milliers de civils tués lors de la campagne simultanée d’Anfal visant les Kurdes en Irak. [74] [78] La fin de la guerre n’a entraîné ni réparations ni changements de frontières. [78] On pense que le coût financier combiné pour les deux combattants a dépassé 1 000 milliards de dollars américains. [78]

Terminologie

La guerre Iran-Irak était à l’origine appelée la guerre du golfe Persique jusqu’à la guerre du golfe Persique de 1990 et 1991, après quoi la guerre précédente a été surnommée la première guerre du golfe Persique . Cependant, outre la guerre Iran-Irak, le conflit Irak-Koweït de 1990, ainsi que la guerre en Irak de 2003 à 2011 ont tous été appelés la deuxième guerre du golfe Persique . [79]

En Iran, la guerre est connue sous le nom de Guerre imposée ( جنگ تحمیلی Jang-e Tahmili ) [78] et de Défense sacrée ( دفاع مقدس Defā’-e Moghaddas ). Les médias d’État en Irak ont surnommé la guerre Qadisiyyah de Saddam ( قادسية صدام , Qādisiyyat Ṣaddām ), en référence à la bataille d’al-Qādisiyyah au VIIe siècle , au cours de laquelle des guerriers arabes ont vaincu l’ empire sassanide lors de la conquête musulmane de l’Iran . [80]

Histoire

Arrière-plan

Relations Iran-Irak

Rencontre de Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , Houari Boumédiène et Saddam Hussein (de gauche à droite) lors des accords d’Alger en 1975.

Rencontre de Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , Houari Boumédiène et Saddam Hussein (de gauche à droite) lors des accords d’Alger en 1975.

En avril 1969, l’Iran a abrogé le traité de 1937 sur le Chatt al-Arab et les navires iraniens ont cessé de payer des péages à l’Irak lorsqu’ils ont utilisé le Chatt al-Arab. [81] Le Shah a soutenu que le traité de 1937 était injuste envers l’Iran parce que presque toutes les frontières fluviales du monde longeaient le thalweg et parce que la plupart des navires qui utilisaient le Chatt al-Arab étaient iraniens. [82] L’Irak a menacé de guerre à cause du mouvement iranien, mais le 24 avril 1969, un pétrolier iranien escorté par des navires de guerre iraniens ( opération conjointe Arvand ) a navigué sur le Chatt al-Arab, et l’Irak – étant l’État militairement le plus faible – n’a rien fait. [83]L’abrogation iranienne du traité de 1937 a marqué le début d’une période de tension irako-iranienne aiguë qui devait durer jusqu’aux accords d’Alger de 1975. [83]

Les relations entre les gouvernements iranien et irakien se sont brièvement améliorées en 1978, lorsque des agents iraniens en Irak ont découvert des plans de coup d’État pro-soviétique contre le gouvernement irakien. Informé de ce complot, Saddam ordonna l’exécution de dizaines d’officiers de son armée et, en signe de réconciliation, expulsa d’Irak Ruhollah Khomeiny , chef exilé de l’opposition cléricale au Shah. Néanmoins, Saddam considérait l’ accord d’Alger de 1975 comme une simple trêve, plutôt qu’un règlement définitif, et attendait une occasion de le contester. [84] [85]

Après la révolution iranienne

Les tensions entre l’Irak et l’Iran ont été alimentées par la révolution islamique iranienne et son apparence de force panislamique , contrairement au nationalisme arabe irakien . [86] Malgré l’objectif de l’Irak de regagner le Chatt al-Arab [note 5] , le gouvernement irakien a d’abord semblé accueillir la révolution iranienne , qui a renversé Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , qui était considéré comme un ennemi commun. [87] Il y a eu de fréquents affrontements le long de la frontière Iran-Irak tout au long de 1980, l’Irak se plaignant publiquement d’au moins 544 incidents et l’Iran citant au moins 797 violations de sa frontière et de son espace aérien. [88]

Ruhollah Khomeiny est arrivé au pouvoir après la révolution iranienne .

Ruhollah Khomeiny est arrivé au pouvoir après la révolution iranienne .

L’ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeiny a appelé les Irakiens à renverser le gouvernement Baas, ce qui a été accueilli avec une colère considérable à Bagdad. [87] Le 17 juillet 1979, malgré l’appel de Khomeiny, Saddam a prononcé un discours faisant l’éloge de la révolution iranienne et a appelé à une amitié irako-iranienne basée sur la non-ingérence dans les affaires intérieures de l’autre. [87] Quand Khomeiny a rejeté l’ouverture de Saddam en appelant à la révolution islamique [84] en Irak, Saddam a été alarmé. [87] La nouvelle administration islamique iranienne était considérée à Bagdad comme une menace irrationnelle et existentielle pour le gouvernement Baas, notamment parce que le parti Baas, de nature laïque,Mouvement chiite en Irak, dont les religieux étaient les alliés de l’Iran en Irak et que Khomeiny considérait comme opprimés. [87]

L’intérêt principal de Saddam pour la guerre peut également provenir de son désir de réparer le supposé “faux” de l’ accord d’Alger , en plus de réaliser enfin son désir de devenir la superpuissance régionale. [84] [89] L’objectif de Saddam était de supplanter l’ Égypte en tant que “leader du monde arabe” et d’atteindre l’ hégémonie sur le golfe Persique. [90] [91] Il a vu la faiblesse accrue de l’Iran en raison de la révolution, des sanctions et de l’isolement international. [92] Saddam avait beaucoup investi dans l’armée irakienne depuis sa défaite contre l’Iran en 1975, achetant de grandes quantités d’armes à l’Union soviétique et à la France. Entre 1973 et 1980 seulement, l’Iraq a acheté environ 1,APC et plus de 200 avions de fabrication soviétique. [93] En 1980, l’Iraq possédait 242 000 soldats (derrière seulement l’Égypte dans le monde arabe), [94] 2 350 chars [95] et 340 avions de combat. [96] En regardant la désintégration de la puissante armée iranienne qui l’a frustré en 1974-1975, il a vu une opportunité d’attaquer, en utilisant la menace de la révolution islamique comme prétexte. [97] [98] Les renseignements militaires irakiens ont rapporté en juillet 1980 qu’en dépit de la rhétorique belliqueuse de l’Iran, “il est clair qu’à l’heure actuelle, l’Iran n’a pas le pouvoir de lancer de vastes opérations offensives contre l’Irak, ou de se défendre à grande échelle”. [99] [100]Quelques jours avant l’invasion irakienne et au milieu d’escarmouches transfrontalières qui s’intensifient rapidement, les services de renseignement militaires irakiens ont de nouveau répété le 14 septembre que “l’organisation de déploiement ennemie n’indique pas d’intentions hostiles et semble adopter un mode plus défensif”. [101]

Certains universitaires écrivant avant l’ouverture d’archives irakiennes autrefois classées, comme Alistair Finlan, ont fait valoir que Saddam avait été entraîné dans un conflit avec l’Iran en raison des affrontements frontaliers et de l’ingérence iranienne dans les affaires intérieures irakiennes. Finlan a déclaré en 2003 que l’invasion irakienne était censée être une opération limitée afin d’envoyer un message politique aux Iraniens pour qu’ils se tiennent à l’écart des affaires intérieures irakiennes, [102] alors que Kevin M. Woods et Williamson Murray ont déclaré en 2014 que l’équilibre de preuves suggèrent que Saddam cherchait “une excuse commode pour la guerre” en 1980. [98]

Le 8 mars 1980, l’Iran a annoncé qu’il retirait son ambassadeur d’Irak, a rétrogradé ses relations diplomatiques au niveau du chargé d’affaires et a exigé que l’Irak fasse de même. [87] [103] Le jour suivant, l’Irak a déclaré l’ambassadeur d’Iran Persona non-grata et a exigé son retrait d’Irak avant le 15 mars. [104]

Préparatifs irakiens

Localisation de la Province du Khouzistan en Iran que l’Irak prévoyait d’annexer

Localisation de la Province du Khouzistan en Iran que l’Irak prévoyait d’annexer

L’Irak a commencé à planifier des offensives, confiant qu’elles réussiraient. L’Iran manquait à la fois de leadership cohérent et de pièces de rechange pour ses équipements de fabrication américaine et britannique. Les Irakiens pouvaient mobiliser jusqu’à 12 divisions mécanisées et le moral était au plus haut. [ citation nécessaire ]

De plus, la zone autour du Chatt al-Arab ne représentait aucun obstacle pour les Irakiens, car ils possédaient du matériel de franchissement de rivière. L’Irak a correctement déduit que les défenses de l’Iran aux points de passage autour des fleuves Karkheh et Karoun étaient en sous-effectif et que les fleuves pouvaient être facilement traversés. Les services de renseignement irakiens ont également été informés que les forces iraniennes dans la Province du Khouzistan (qui se composaient de deux divisions avant la révolution) ne se composaient désormais que de plusieurs bataillons mal équipés et en sous-effectif . Seule une poignée d’ unités de chars de la taille d’une entreprise sont restées opérationnelles. [85]

Les seuls scrupules que les Irakiens avaient concernaient l’ armée de l’air de la République islamique d’Iran (anciennement l’ armée de l’air impériale iranienne ). Malgré la purge de plusieurs pilotes et commandants clés, ainsi que le manque de pièces de rechange, l’armée de l’air a montré sa puissance lors de soulèvements et de rébellions locaux. Ils étaient également actifs après l’échec de la tentative américaine de sauver ses otages , l’opération Eagle Claw . Sur la base de ces observations, les dirigeants irakiens ont décidé de mener une frappe aérienne surprise contre l’infrastructure de l’armée de l’air iranienne avant l’invasion principale. [85]

Préparations iraniennes

En Iran, de graves purges d’officiers (y compris de nombreuses exécutions ordonnées par Sadegh Khalkhali , le nouveau juge du tribunal révolutionnaire ) et des pénuries de pièces de rechange pour les équipements iraniens de fabrication américaine et britannique avaient paralysé l’ armée iranienne autrefois puissante . Entre février et septembre 1979, le gouvernement iranien a exécuté 85 généraux de haut rang et forcé tous les généraux de division et la plupart des généraux de brigade à une retraite anticipée. [87]

Le président iranien Abolhassan Banisadr , qui était également commandant en chef, sur un canon antichar sans recul de 106 mm monté sur Jeep . Banisadr a été destitué en juin 1981.

Le président iranien Abolhassan Banisadr , qui était également commandant en chef, sur un canon antichar sans recul de 106 mm monté sur Jeep . Banisadr a été destitué en juin 1981.

En septembre 1980, le gouvernement avait purgé 12 000 officiers de l’armée. [87] Ces purges ont entraîné un déclin drastique des capacités opérationnelles de l’armée iranienne. [87] Leur armée régulière (qui, en 1978, était considérée comme la cinquième plus puissante du monde) [105] avait été gravement affaiblie. Le taux de désertion avait atteint 60% et le corps des officiers était dévasté. Les soldats et les aviateurs les plus qualifiés ont été exilés, emprisonnés ou exécutés. Tout au long de la guerre, l’Iran n’a jamais réussi à se remettre complètement de cette fuite du capital humain . [106]

Des sanctions continues ont empêché l’Iran d’acquérir de nombreuses armes lourdes, telles que des chars et des avions. Lorsque l’invasion a eu lieu, de nombreux pilotes et officiers ont été libérés de prison ou ont vu leurs exécutions commuées pour combattre les Irakiens. En outre, de nombreux officiers subalternes ont été promus généraux, ce qui a permis à l’armée d’être plus intégrée au régime à la fin de la guerre, comme c’est le cas aujourd’hui. [106] L’Iran avait encore au moins 1 000 chars opérationnels et plusieurs centaines d’avions fonctionnels, et pouvait cannibaliser l’équipement pour se procurer des pièces de rechange. [107]

Pendant ce temps, une nouvelle organisation paramilitaire a pris de l’importance en Iran, le Corps des gardiens de la révolution islamique (souvent abrégé en gardiens de la révolution et connu en Iran sous le nom de Sepah-e-Pasdaran ). [108] Cela visait à protéger le nouveau régime et à contrebalancer l’armée, considérée comme moins loyale. Bien qu’ils aient été formés en tant qu’organisation paramilitaire, après l’invasion irakienne, ils ont été contraints d’agir comme une armée régulière. Au départ, ils ont refusé de se battre aux côtés de l’armée, ce qui a entraîné de nombreuses défaites, mais en 1982, les deux groupes ont commencé à mener des opérations combinées. [107]

Une autre milice paramilitaire a été fondée en réponse à l’invasion, l'”Armée des 20 millions”, communément appelée Basij . [109] Les Basij étaient mal armés et avaient des membres aussi jeunes que 12 ans et aussi âgés que 70 ans. Ils agissaient souvent en collaboration avec les Gardiens de la révolution, lançant des soi-disant attaques par vague humaine et d’autres campagnes contre les Irakiens. [109] Ils étaient subordonnés aux Gardiens de la révolution et ils constituaient la majeure partie de la main-d’œuvre utilisée dans les attaques des Gardiens de la révolution. [84]

Stephen Pelletiere a écrit dans son livre de 1992 The Iran-Iraq War: Chaos in a Vacuum :

La vague humaine a été largement mal interprétée à la fois par les médias populaires occidentaux et par de nombreux universitaires. Les Iraniens ne se sont pas contentés de rassembler des masses d’individus, de les diriger vers l’ennemi et d’ordonner une charge. Les vagues étaient composées des escouades de 22 hommes mentionnées ci-dessus [en réponse à l’appel de Khomeiny pour que le peuple vienne à la défense de l’Iran, chaque mosquée a organisé 22 volontaires en une escouade]. Chaque escouade s’est vu attribuer un objectif précis. Au combat, ils se précipitaient pour accomplir leurs missions et donnaient ainsi l’impression d’une vague humaine se déversant sur les lignes ennemies. [110]

Conflits frontaliers menant à la guerre

Le Chatt al-Arab à la frontière Iran-Irak

Le Chatt al-Arab à la frontière Iran-Irak

Le différend le plus important concernait la voie navigable de Chatt al-Arab . L’Iran a répudié la ligne de démarcation établie dans la convention anglo-ottomane de Constantinople de novembre 1913. L’Iran a demandé que la frontière longe le thalweg , le point le plus profond du chenal navigable. L’Irak, encouragé par la Grande- Bretagne , emmène l’Iran à la Société des Nationsen 1934, mais leur désaccord n’a pas été résolu. Enfin, en 1937, l’Iran et l’Irak ont signé leur premier traité frontalier. Le traité a établi la frontière de la voie navigable sur la rive est de la rivière à l’exception d’une zone de mouillage de 6 kilomètres (4 mi) près d’Abadan, qui a été attribuée à l’Iran et où la frontière longeait le thalweg. L’Iran a envoyé une délégation en Irak peu après le coup d’État du Baas en 1969 et, lorsque l’Irak a refusé de poursuivre les négociations sur un nouveau traité, le traité de 1937 a été retiré par l’Iran. L’abrogation iranienne du traité de 1937 a marqué le début d’une période de tension irako-iranienne aiguë qui devait durer jusqu’aux accords d’Alger de 1975.

Les affrontements de Shatt al-Arab de 1974 à 1975 étaient une précédente confrontation irano-irakienne dans la région de la voie navigable de Shatt al-Arab au milieu des années 1970. Près de 1 000 ont été tués dans les affrontements. C’était le différend le plus important sur la voie navigable Chatt al-Arab à l’époque moderne, avant la guerre Iran-Irak.

Le 10 septembre 1980, l’Irak a récupéré de force des territoires à Zain al-Qaws et Saif Saad qui lui avaient été promis aux termes de l’ accord d’Alger de 1975 mais que l’Iran n’avait jamais cédés, ce qui a conduit l’Iran et l’Irak à déclarer le traité nul et non avenu. , respectivement les 14 et 17 septembre. En conséquence, le seul différend frontalier en suspens entre l’Iran et l’Iraq au moment de l’invasion iraquienne du 22 septembre était la question de savoir si les navires iraniens arboreraient des pavillons irakiens et paieraient des redevances de navigation irakiennes pour un tronçon du fleuve Chatt al-Arab qui s’étend sur plusieurs milles. [111] [112]

Déroulement de la guerre

1980 : Invasion irakienne

Skytrain C-47 iranien détruit

Skytrain C-47 iranien détruit

L’Irak a lancé une invasion à grande échelle de l’Iran le 22 septembre 1980. L’ armée de l’air irakienne a lancé des frappes aériennes surprises sur dix aérodromes iraniens dans le but de détruire l’ armée de l’air iranienne . [87] L’attaque n’a pas endommagé de manière significative l’armée de l’air iranienne; il a endommagé une partie de l’infrastructure de la base aérienne iranienne, mais n’a pas réussi à détruire un nombre important d’avions. L’armée de l’air irakienne n’a pu frapper en profondeur qu’avec quelques avions MiG-23BN , Tu-22 et Su-20 , [113] et l’Iran avait construit des abris d’avions renforcés où la plupart de ses avions de combat étaient stockés.

Le lendemain, l’Irak a lancé une invasion terrestre le long d’un front mesurant 644 km (400 mi) en trois attaques simultanées. [87] Le but de l’invasion, selon Saddam, était d’émousser le mouvement de Khomeiny et de contrecarrer ses tentatives d’ exporter sa révolution islamique en Irak et dans les États du golfe Persique. [103] Saddam espérait qu’une attaque contre l’Iran porterait un tel coup au prestige de l’Iran qu’elle conduirait à la chute du nouveau gouvernement, ou au moins mettrait fin aux appels de l’Iran à son renversement. [87]

Sur les six divisions irakiennes qui ont envahi par voie terrestre, quatre ont été envoyées au Khouzistan, situé près de l’extrémité sud de la frontière, pour couper le Chatt al-Arab [note 5] du reste de l’Iran et établir une zone de sécurité territoriale. [87] : 22 Les deux autres divisions ont envahi à travers la partie nord et centrale de la frontière pour empêcher une contre-attaque iranienne. [87] Deux des quatre divisions irakiennes, une mécanisée et une blindée, ont opéré près de l’extrémité sud et ont commencé un siège des villes portuaires stratégiquement importantes d’ Abadan et de Khorramshahr . [87] : 22

Les deux divisions blindées sécurisent le territoire délimité par les villes de Khorramshahr , Ahvaz , Susangerd et Musian . [87] : 22 Sur le front central, les Irakiens ont occupé Mehran , ont avancé vers les contreforts des monts Zagros et ont pu bloquer la route d’invasion traditionnelle Téhéran-Bagdad en sécurisant le territoire en avant de Qasr-e Shirin , en Iran. [87] : 23 Sur le front nord, les Irakiens ont tenté d’établir une forte position défensive face à Suleimaniya pour protéger le complexe pétrolier irakien de Kirkouk . [87]: 23 Les espoirs irakiens d’un soulèvement des Arabes ethniques du Khuzestan ne se sont pas matérialisés, car la plupart des Arabes ethniques sont restés fidèles à l’Iran. [87] Les troupes irakiennes avançant en Iran en 1980 ont été décrites par Patrick Brogan comme “mal dirigées et manquant d’esprit offensif”. [114] : 261 La première attaque à l’arme chimique connue de l’Irak contre l’Iran a probablement eu lieu lors des combats autour de Susangerd. [115]

Tomcats F-14A iraniens équipés de missiles AIM-54A , AIM-7 et AIM-9 .

Tomcats F-14A iraniens équipés de missiles AIM-54A , AIM-7 et AIM-9 .

Bien que l’invasion aérienne irakienne ait surpris les Iraniens, l’armée de l’air iranienne a riposté le lendemain avec une attaque à grande échelle contre les bases aériennes et les infrastructures irakiennes dans le cadre de l’opération Kaman 99 . Des groupes d’ avions de chasse F-4 Phantom et F-5 Tiger ont attaqué des cibles dans tout l’Irak, telles que des installations pétrolières, des barrages, des usines pétrochimiques et des raffineries de pétrole, et comprenaient la base aérienne de Mossoul , Bagdad et la raffinerie de pétrole de Kirkouk. L’Irak a été surpris par la force des représailles, qui ont causé de lourdes pertes aux Irakiens et des perturbations économiques, mais les Iraniens ont subi de lourdes pertes et perdu de nombreux avions et équipages au profit des défenses aériennes irakiennes.

Les hélicoptères de combat AH-1 Cobra de l’aviation de l’armée iranienne ont lancé des attaques contre les divisions irakiennes en progression, ainsi que des F-4 Phantoms armés de missiles AGM-65 Maverick ; [84] ils ont détruit de nombreux véhicules blindés et ont entravé l’avance irakienne, bien que ne l’arrêtant pas complètement. [116] [117] Pendant ce temps, les attaques aériennes irakiennes contre l’Iran ont été repoussées par les chasseurs intercepteurs F-14A Tomcat iraniens , utilisant des missiles AIM-54A Phoenix , qui ont abattu une douzaine de chasseurs irakiens de construction soviétique au cours des deux premiers jours de bataille. [116] [ douteux – discuter ]

L’armée régulière iranienne, les forces de police, les volontaires Basij et les gardiens de la révolution ont tous mené leurs opérations séparément; ainsi, les forces d’invasion irakiennes n’ont pas fait face à une résistance coordonnée. [87] Cependant, le 24 septembre, la marine iranienne a attaqué Basra , en Irak, détruisant deux terminaux pétroliers près du port irakien Faw, ce qui a réduit la capacité de l’Irak à exporter du pétrole. [87] Les forces terrestres iraniennes (principalement composées des Gardiens de la révolution) se sont retirées dans les villes, où elles ont mis en place des défenses contre les envahisseurs. [118]

Le 30 septembre, l’armée de l’air iranienne a lancé l’opération Scorch Sword , frappant et endommageant gravement le réacteur nucléaire d’Osirak presque terminé près de Bagdad. [87] Avant le 1 octobre, Bagdad avait été soumis à huit attaques aériennes. [87] : 29 En réponse, l’Irak a lancé des frappes aériennes contre des cibles iraniennes. [87] [116]

La frontière montagneuse entre l’Iran et l’Irak a rendu une invasion terrestre profonde presque impossible, [119] et des frappes aériennes ont été utilisées à la place. Les premières vagues de l’invasion ont été une série de frappes aériennes ciblées sur les aérodromes iraniens. L’Irak a également tenté de bombarder Téhéran, la capitale et le centre de commandement de l’Iran, pour le soumettre. [87] [113]

Première bataille de Khorramshahr

La résistance des Iraniens en infériorité numérique et en armes à Khorramshahr a ralenti les Irakiens pendant un mois.

La résistance des Iraniens en infériorité numérique et en armes à Khorramshahr a ralenti les Irakiens pendant un mois.

Le 22 septembre, une bataille prolongée a commencé dans la ville de Khorramshahr, faisant finalement 7 000 morts de chaque côté. [87] Reflétant la nature sanglante de la lutte, les Iraniens en sont venus à appeler Khorramshahr “la ville du sang”. [87]

La bataille a commencé par des raids aériens irakiens contre des points clés et des divisions mécanisées avançant sur la ville dans une formation en forme de croissant. Ils ont été ralentis par les attaques aériennes iraniennes et les troupes des Gardiens de la révolution avec des fusils sans recul , des grenades propulsées par fusée et des cocktails Molotov . [120] Les Iraniens ont inondé les zones marécageuses autour de la ville, forçant les Irakiens à traverser d’étroites bandes de terre. [120] Les chars irakiens ont lancé des attaques sans soutien d’infanterie, et de nombreux chars ont été perdus au profit des équipes antichars iraniennes. [120]Cependant, le 30 septembre, les Irakiens avaient réussi à chasser les Iraniens de la périphérie de la ville. Le lendemain, les Irakiens ont lancé des attaques d’infanterie et de blindés dans la ville. Après de violents combats de maison en maison , les Irakiens sont repoussés. Le 14 octobre, les Irakiens lancent une seconde offensive. Les Iraniens ont lancé un retrait contrôlé de la ville, rue par rue. [120] Avant le 24 octobre, la plupart de la ville a été capturée et les Iraniens évacués à travers le Fleuve Karun. Certains partisans sont restés et les combats se sont poursuivis jusqu’au 10 novembre.

L’avancée irakienne cale

Le peuple iranien, plutôt que de se retourner contre sa République islamique encore faible, s’est rallié à son pays. Environ 200 000 soldats frais étaient arrivés au front en novembre, dont beaucoup étaient des volontaires idéologiquement engagés. [121]

7:17 Siège d’Abadan , guerre Iran-Irak

Bien que Khorramshahr ait finalement été capturé, la bataille avait suffisamment retardé les Irakiens pour permettre le déploiement à grande échelle de l’armée iranienne. [87] En novembre, Saddam a ordonné à ses forces d’avancer vers Dezful et Ahvaz et d’assiéger les deux villes. Cependant, l’offensive irakienne avait été gravement endommagée par les milices et la puissance aérienne iraniennes. L’armée de l’air iranienne avait détruit les dépôts de ravitaillement et de carburant de l’armée irakienne, et étranglait le pays par un siège aérien. [116] Les approvisionnements de l’Iran n’avaient pas été épuisés, malgré les sanctions, et l’armée a souvent cannibalisé les pièces de rechange d’autres équipements et a commencé à chercher des pièces sur le marché noir. Le 28 novembre, l’Iran a lancéOpération Morvarid (Pearl), une attaque aérienne et maritime combinée qui a détruit 80% de la marine irakienne et tous ses sites radar dans la partie sud du pays. Lorsque l’Irak a assiégé Abadan et retranché ses troupes autour de la ville, il n’a pas été en mesure de bloquer le port, ce qui a permis à l’Iran de ravitailler Abadan par voie maritime. [122]

Les réserves stratégiques de l’Irak avaient été épuisées et il lui manquait désormais le pouvoir de lancer des offensives majeures jusqu’à la fin de la guerre. [87] Le 7 décembre, Hussein a annoncé que l’Irak allait sur la défensive. [87] À la fin de 1980, l’Irak avait détruit environ 500 chars iraniens de fabrication occidentale et en avait capturé 100 autres. [123] [124]

1981 : Impasse

Pendant les huit mois suivants, les deux camps étaient sur une position défensive (à l’exception de la bataille de Dezful ), car les Iraniens avaient besoin de plus de temps pour réorganiser leurs forces après les dégâts infligés par la purge de 1979-1980. [87] Pendant cette période, les combats consistaient principalement en duels d’artillerie et en raids. [87] L’Irak avait mobilisé 21 divisions pour l’invasion, tandis que l’Iran a riposté avec seulement 13 divisions de l’armée régulière et une brigade . Parmi les divisions régulières, seules sept ont été déployées à la frontière. La guerre s’est enlisée dans une guerre de tranchées de style Première Guerre mondiale avec des chars et des armes modernes de la fin du XXe siècle. En raison de la puissance des armes antichars telles que le RPG-7, la manœuvre blindée des Irakiens était très coûteuse et ils retranchaient par conséquent leurs chars dans des positions statiques. [84] [107]

L’Irak a également commencé à tirer des missiles Scud sur Dezful et Ahvaz , et a utilisé des bombardements terroristes pour amener la guerre à la population civile iranienne. [122] L’Iran a lancé des dizaines “d’assauts de vagues humaines”.

Bataille de Dezful

Le président iranien Abulhassan Banisadr sur le front

Le président iranien Abulhassan Banisadr sur le front

Le 5 janvier 1981, l’Iran avait suffisamment réorganisé ses forces pour lancer une offensive à grande échelle, l’opération Nasr (Victoire). [120] [125] [126] Les Iraniens ont lancé leur offensive blindée majeure depuis Dezful en direction de Susangerd , composée de brigades de chars des 16e Qazvin , 77e Khorasan et 92e divisions blindées du Khuzestan , [126] et ont franchi les lignes irakiennes . [87] : 32 Cependant, les chars iraniens avaient couru à travers les lignes irakiennes avec leurs flancs non protégés et sans soutien d’infanterie; [84] en conséquence, ils ont été coupés par les chars irakiens. [87]Lors de la bataille de Dezful qui a suivi, les divisions blindées iraniennes ont été presque anéanties dans l’une des plus grandes batailles de chars de la guerre. [87] Lorsque les chars iraniens ont tenté de manœuvrer, ils se sont retrouvés coincés dans la boue des marais et de nombreux chars ont été abandonnés. [120] Les Irakiens ont perdu 45 chars T-55 et T-62 , tandis que les Iraniens ont perdu 100 à 200 chars Chieftain et M-60 . Les journalistes ont dénombré environ 150 chars iraniens détruits ou abandonnés, ainsi que 40 chars irakiens. [87] 141 Iraniens ont été tués pendant la bataille. [126]

La bataille avait été ordonnée par le président iranien Abulhassan Banisadr , qui espérait qu’une victoire pourrait consolider sa position politique qui se détériorait ; au lieu de cela, l’échec a accéléré sa chute. [87] : 71 Beaucoup de problèmes de l’Iran ont eu lieu à cause de luttes intestines politiques entre le président Banisadr, qui a soutenu l’armée régulière, et les extrémistes qui ont soutenu l’IRGC. Une fois qu’il a été destitué et que la compétition a pris fin, les performances de l’armée iranienne se sont améliorées.

Le président irakien Saddam Hussein et Massoud Radjavi , le chef du MEK et du Conseil de la résistance nationale iranienne (CNRI) en 1988.

Le président irakien Saddam Hussein et Massoud Radjavi , le chef du MEK et du Conseil de la résistance nationale iranienne (CNRI) en 1988.

Le gouvernement de la République islamique d’Iran a été davantage distrait par des combats internes entre le régime et les Moudjahidin e-Khalq (MEK) dans les rues des principales villes iraniennes en juin 1981 et de nouveau en septembre. [114] : 250–251 En 1983, le MEK a commencé une alliance avec l’Irak suite à une rencontre entre le dirigeant du MEK Massoud Radjavi et le Premier ministre irakien Tariq Aziz . [127] [128] [129] [130]

En 1984 , Banisadr a quitté la coalition en raison d’un différend avec Radjavi . En 1986, Radjavi a déménagé de Paris en Irak et a établi une base à la frontière iranienne. [note 6] La bataille de Dezful est devenue une bataille critique dans la pensée militaire iranienne. Moins d’accent a été mis sur l’armée avec ses tactiques conventionnelles, et plus l’accent a été mis sur les gardiens de la révolution avec ses tactiques non conventionnelles. [120] [131]

Attaque sur H3

L’ attaque surprise de la base aérienne H-3 est considérée comme l’une des opérations aériennes les plus sophistiquées de la guerre.

L’ attaque surprise de la base aérienne H-3 est considérée comme l’une des opérations aériennes les plus sophistiquées de la guerre.

L’armée de l’air irakienne, gravement endommagée par les Iraniens, a été déplacée vers la base aérienne H-3 dans l’ouest de l’Irak, près de la frontière jordanienne et loin de l’Iran. Cependant, le 3 avril 1981, l’armée de l’air iranienne a utilisé huit chasseurs-bombardiers F-4 Phantom, quatre F-14 Tomcat, trois ravitailleurs Boeing 707 et un avion de commandement Boeing 747 pour lancer une attaque surprise sur H3 , détruisant 27 à 50 avions. Avions de chasse et bombardiers irakiens. [132]

Malgré l’attaque réussie de la base aérienne H-3 (en plus d’autres attaques aériennes), l’armée de l’air iranienne a été forcée d’annuler son offensive aérienne réussie de 180 jours. De plus, ils ont abandonné leur tentative de contrôle de l’ espace aérien iranien . Ils avaient été sérieusement affaiblis par les sanctions et les purges d’avant-guerre et encore plus endommagés par une nouvelle purge après la crise de destitution du président Banisadr . [133] L’armée de l’air iranienne n’a pas pu survivre à une nouvelle attrition et a décidé de limiter ses pertes, abandonnant les efforts pour contrôler l’ espace aérien iranien.. L’armée de l’air iranienne combattra désormais sur la défensive, essayant de dissuader les Irakiens plutôt que de les engager. Alors que tout au long de 1981-1982, l’armée de l’air irakienne resterait faible, au cours des prochaines années, elle se réarmerait et se développerait à nouveau, et commencerait à reprendre l’initiative stratégique. [134]

Introduction de l’attaque par vague humaine

Les Iraniens souffraient d’une pénurie d’armes lourdes, [107] : 225 mais disposaient d’un grand nombre de troupes de volontaires dévoués, ils ont donc commencé à utiliser des attaques par vagues humaines contre les Irakiens. En règle générale, un assaut iranien commencerait par des Basij mal entraînés qui lanceraient les principales vagues d’assauts humains pour submerger en masse les parties les plus faibles des lignes irakiennes (parfois même en nettoyant physiquement les champs de mines). [107] [135] Cela serait suivi par l’infanterie des gardiens de la révolution plus expérimentée, qui violerait les lignes irakiennes affaiblies, [107] [118] et suivie par l’armée régulière utilisant des forces mécanisées, qui manœuvreraient à travers la brèche et tenter d’encercler et de vaincre l’ennemi.[107] [120]

Soldat iranien tenant un sac intraveineux pendant la guerre Iran-Irak

Soldat iranien tenant un sac intraveineux pendant la guerre Iran-Irak

Selon l’ historien Stephen C. Pelletiere, l’idée des «attaques par vagues humaines» iraniennes était une idée fausse. [136] Au lieu de cela, la tactique iranienne consistait à utiliser des groupes d’ escouades d’infanterie de 22 hommes , qui avançaient pour attaquer des objectifs spécifiques. Alors que les escouades se précipitaient pour exécuter leurs missions, cela donnait l’impression d’une “attaque par vague humaine”. Néanmoins, l’idée d ‘«attaques par vagues humaines» est restée pratiquement synonyme de tout assaut frontal d’infanterie à grande échelle mené par l’Iran. [136] Un grand nombre de troupes seraient utilisées, visant à submerger les lignes irakiennes (généralement la partie la plus faible, généralement occupée par l’ armée populaire irakienne ), quelles que soient les pertes.

Selon l’ancien général irakien Ra’ad al-Hamdani , les charges de la vague humaine iranienne consistaient en des “civils” armés qui transportaient eux-mêmes la plupart de leur équipement nécessaire au combat et manquaient souvent de commandement, de contrôle et de logistique . [137] Les opérations étaient souvent menées pendant la nuit et les opérations de déception, les infiltrations et les manœuvres sont devenues plus courantes. [122] Les Iraniens renforceraient également les forces d’infiltration avec de nouvelles unités pour maintenir leur élan. Une fois qu’un point faible était trouvé, les Iraniens concentraient toutes leurs forces dans cette zone pour tenter de percer avec des attaques de vagues humaines. [137]

Les attaques de la vague humaine, bien qu’extrêmement sanglantes (des dizaines de milliers de soldats sont morts dans le processus), [135] lorsqu’elles sont utilisées en combinaison avec l’infiltration et la surprise, ont causé d’importantes défaites irakiennes. Alors que les Irakiens creuseraient dans leurs chars et leur infanterie dans des positions statiques et retranchées, les Iraniens parviendraient à percer les lignes et à encercler des divisions entières. [107] Le simple fait que les forces iraniennes aient utilisé la guerre de manœuvre par leur infanterie légère contre les défenses irakiennes statiques était souvent le facteur décisif dans la bataille. [118] Cependant, le manque de coordination entre l’armée iranienne et l’IRGC et les pénuries d’armes lourdes ont joué un rôle préjudiciable, souvent la plupart de l’infanterie n’étant pas soutenue par l’artillerie et les blindés. [107][118]

Opération-huitième Imam

Après l’arrêt de l’offensive irakienne en mars 1981, il y a eu peu de changement sur le front autre que l’Iran reprenant les hauteurs au-dessus de Susangerd en mai. À la fin de 1981, l’Iran est revenu à l’offensive et a lancé une nouvelle opération ( Opération Samen-ol-A’emeh (Le Huitième Imam)), [138] mettant fin au siège irakien d’Abadan du 27 au 29 septembre 1981. [87] : 9 Les Iraniens ont utilisé une force combinée d’artillerie de l’armée régulière avec de petits groupes de blindés, soutenus par l’infanterie Pasdaran (IRGC) et Basij. [133] Le 15 octobre, après avoir brisé le siège, un grand convoi iranien a été pris en embuscade par des chars irakiens et, lors de la bataille de chars qui a suivi, l’Iran a perdu 20 chefs .et d’autres véhicules blindés et se sont retirés du territoire précédemment conquis. [139]

Opération Tariq al-Qods

Le 29 novembre 1981, l’Iran a lancé l’opération Tariq al-Qods avec trois brigades de l’armée et sept brigades des gardiens de la révolution. Les Irakiens n’ont pas patrouillé correctement leurs zones occupées et les Iraniens ont construit une route de 14 km (14 000 m; 8,7 mi) à travers les dunes de sable non gardées, lançant leur attaque depuis l’arrière irakien. [120] La ville de Bostan a été reprise aux divisions irakiennes le 7 décembre. [87] : 10 À cette époque, l’armée irakienne connaissait de graves problèmes de moral, [87] aggravés par le fait que l’opération Tariq al-Qods marquait la première utilisation des tactiques iraniennes de “vague humaine”, où l’ infanterie légère des Gardiens de la révolutionchargés à plusieurs reprises sur des positions irakiennes, souvent sans le soutien de blindés ou de puissance aérienne. [87] La chute de Bostan a exacerbé les problèmes logistiques des Irakiens, les forçant à utiliser une route détournée d’Ahvaz vers le sud pour réapprovisionner leurs troupes. [87] 6 000 Iraniens et plus de 2 000 Irakiens ont été tués dans l’opération. [87]

1982 : retraite irakienne, offensive iranienne

Avion iranien Northrop F-5 pendant la guerre Iran-Irak

Avion iranien Northrop F-5 pendant la guerre Iran-Irak

Les Irakiens, réalisant que les Iraniens prévoyaient d’attaquer, décidèrent de les devancer avec l’opération al-Fawz al-‘Azim (succès suprême) [140] le 19 mars. Utilisant un grand nombre de chars, d’hélicoptères et d’avions de chasse, ils ont attaqué l’accumulation iranienne autour du col de Roghabiyeh. Bien que Saddam et ses généraux aient supposé qu’ils avaient réussi, en réalité les forces iraniennes sont restées entièrement intactes. [84] Les Iraniens avaient concentré une grande partie de leurs forces en les amenant directement des villes et villages de tout l’Iran via des trains, des bus et des voitures privées. La concentration des forces ne ressemblait pas à une accumulation militaire traditionnelle, et bien que les Irakiens aient détecté une accumulation de population près du front, ils n’ont pas réalisé qu’il s’agissait d’une force d’attaque. [137]En conséquence, l’armée de Saddam n’était pas préparée aux offensives iraniennes à venir. [84]

Opération Victoire indéniable

La prochaine offensive majeure de l’Iran, dirigée par le colonel Ali Sayad Shirazi , était l’opération Victoire indéniable . Le 22 mars 1982, l’Iran lance une attaque qui prend les forces irakiennes par surprise : à l’aide d’hélicoptères Chinook , elles atterrissent derrière les lignes irakiennes, font taire leur artillerie et s’emparent d’un quartier général irakien. [84] Le Basij iranien a alors lancé des attaques de “vague humaine”, composées de 1 000 combattants par vague. Bien qu’ils aient subi de lourdes pertes, ils ont finalement franchi les lignes irakiennes. [ citation nécessaire ]

Les gardiens de la révolution et l’armée régulière ont suivi en encerclant les 9e et 10e divisions blindées et la 1re division mécanisée irakiennes qui avaient campé près de la ville iranienne de Shush . Les Irakiens ont lancé une contre-attaque en utilisant leur 12e division blindée pour briser l’encerclement et sauver les divisions encerclées. Les chars irakiens ont été attaqués par 95 avions de combat iraniens F-4 Phantom et F-5 Tiger, détruisant une grande partie de la division. [141]

L’opération Undeniable Victory était une victoire iranienne; Les forces irakiennes ont été chassées de Shush, Dezful et Ahvaz. Les forces armées iraniennes ont détruit 320 à 400 chars et véhicules blindés irakiens dans un succès coûteux. Au cours du premier jour de la bataille, les Iraniens ont perdu 196 chars. [84] À cette époque, la majeure partie de la province du Khuzestan avait été reprise. [87]

Opération Beit al-Moqaddas

Épave de char irakien T-62 dans la Province du Khouzistan , Iran

Épave de char irakien T-62 dans la Province du Khouzistan , Iran

En préparation de l’opération Beit al-Moqaddas , les Iraniens avaient lancé de nombreux raids aériens contre les bases aériennes irakiennes, détruisant 47 avions à réaction (y compris les tout nouveaux avions de chasse Mirage F-1 irakiens en provenance de France) ; cela a donné aux Iraniens une supériorité aérienne sur le champ de bataille tout en leur permettant de surveiller les mouvements des troupes irakiennes. [84]

Le 29 avril, l’Iran lance l’offensive. 70 000 membres des Gardiens de la révolution et du Basij ont frappé sur plusieurs axes – Bostan, Susangerd, la rive ouest de la rivière Karun et Ahvaz. Le Basij a lancé des attaques par vague humaine, qui ont été suivies par le soutien de l’armée régulière et des gardiens de la révolution, ainsi que des chars et des hélicoptères. [84] Sous la forte pression iranienne, les forces irakiennes se sont retirées. Le 12 mai, l’Iran avait chassé toutes les forces irakiennes de la région de Susangerd. [87] : 36 Les Iraniens ont capturé plusieurs milliers de soldats irakiens et un grand nombre de chars. [84] Néanmoins, les Iraniens ont également subi de nombreuses pertes, en particulier parmi les Basij.

Les Irakiens se sont retirés dans la rivière Karun, avec seulement Khorramshahr et quelques zones périphériques restant en leur possession. [107] Saddam a ordonné que 70 000 soldats soient placés autour de la ville de Khorramshahr. Les Irakiens ont créé une ligne de défense construite à la hâte autour de la ville et des zones périphériques. [84] Pour décourager les atterrissages de commandos aéroportés, les Irakiens ont également placé des pointes métalliques et détruit des voitures dans des zones susceptibles d’être utilisées comme zones d’atterrissage de troupes. Saddam Hussein a même visité Khorramshahr dans un geste dramatique, jurant que la ville ne serait jamais abandonnée. [84] Cependant, le seul point de réapprovisionnement de Khorramshahr était à travers le Chatt al-Arab [note 5], et l’armée de l’air iranienne a commencé à bombarder les ponts d’approvisionnement de la ville, tandis que leur artillerie se concentrait sur la garnison assiégée.

Libération de Khorramshahr (deuxième bataille de Khorramshahr)

Des soldats irakiens se rendent après la libération de Khorramshahr

Des soldats irakiens se rendent après la libération de Khorramshahr

Aux petites heures du matin du 23 mai 1982, les Iraniens ont commencé la route vers Khorramshahr à travers la rivière Karun . [87] Cette partie de l’opération Beit al-Moqaddas était dirigée par la 77e division Khorasan avec des chars ainsi que les gardiens de la révolution et Basij. Les Iraniens ont frappé les Irakiens avec des frappes aériennes destructrices et des barrages d’artillerie massifs, ont traversé la rivière Karun, capturé des têtes de pont et lancé des attaques de vagues humaines vers la ville. La barricade défensive de Saddam s’est effondrée ; [84] en moins de 48 heures de combats, la ville tombe et 19 000 Irakiens se rendent aux Iraniens. Au total, 10 000 Irakiens ont été tués ou blessés à Khorramshahr, tandis que les Iraniens ont subi 30 000 pertes. [142]Pendant toute l’opération Beit al-Moqaddas, 33 000 soldats irakiens ont été capturés par les Iraniens. [84]

État des forces armées irakiennes

Les combats avaient meurtri l’armée irakienne : ses effectifs étaient passés de 210 000 à 150 000 hommes ; plus de 20 000 soldats irakiens ont été tués et plus de 30 000 capturés ; deux des quatre divisions blindées actives et au moins trois divisions mécanisées sont tombées à moins d’un effectif de brigade; et les Iraniens avaient capturé plus de 450 chars et véhicules blindés de transport de troupes. [143]

L’armée de l’air irakienne a également été laissée en mauvais état : après avoir perdu jusqu’à 55 appareils depuis début décembre 1981, elle ne disposait que de 100 chasseurs-bombardiers et intercepteurs intacts . Un transfuge qui a fait voler son MiG-21 en Syrie en juin 1982 a révélé que l’armée de l’air irakienne ne disposait que de trois escadrons de chasseurs-bombardiers capables de monter des opérations en Iran. L’armée de l’air irakienne était en meilleure forme et pouvait encore exploiter plus de 70 hélicoptères. [143] Malgré cela, les Irakiens détenaient toujours 3 000 chars, tandis que l’Iran en détenait 1 000. [84]

À ce stade, Saddam a estimé que son armée était trop démoralisée et endommagée pour s’accrocher au Khouzistan et à de grandes étendues du territoire iranien, et a retiré ses forces restantes, les redéployant en défense le long de la frontière. [87] Cependant, ses troupes ont continué à occuper certaines zones frontalières iraniennes clés de l’Iran, y compris les territoires contestés qui ont incité son invasion, notamment la voie navigable Chatt al-Arab. [84] [144] En réponse à leurs échecs contre les Iraniens à Khorramshahr, Saddam a ordonné l’exécution des généraux Juwad Shitnah et Salah al-Qadhi et des colonels Masa et al-Jalil. [137] Au moins une douzaine d’autres officiers de haut rang ont également été exécutés pendant cette période. [133]Cela est devenu une punition de plus en plus courante pour ceux qui l’ont échoué au combat. [137]

Réponse internationale en 1982

En avril 1982, le régime baasiste rival en Syrie , l’un des rares pays à soutenir l’Iran, a fermé l’ oléoduc Kirkuk-Baniyas qui avait permis au pétrole irakien d’atteindre les pétroliers sur la Méditerranée, réduisant le budget irakien de 5 milliards de dollars par mois. [87] Le journaliste Patrick Brogan a écrit : “Il est apparu pendant un moment que l’Irak serait étranglé économiquement avant d’être vaincu militairement.” [114] : 260 La fermeture par la Syrie de l’oléoduc Kirkuk-Baniyas a laissé l’Irak avec l’oléoduc vers la Turquie comme seul moyen d’exporter du pétrole, ainsi que le transport du pétrole par camion-citerne jusqu’au port d’Aqaba en Jordanie. [145]Cependant, l’oléoduc turc n’avait qu’une capacité de 500 000 barils par jour (79 000 m 3 /j), ce qui était insuffisant pour payer la guerre. [25] : 160 Cependant, l’Arabie saoudite, le Koweït et les autres États du Golfe ont sauvé l’Irak de la faillite [87] en lui versant en moyenne 60 milliards de dollars de subventions par an. [114] : 263 [ clarification nécessaire ] Bien que l’Irak ait été auparavant hostile envers les autres États du Golfe, “la menace de l’intégrisme persan était bien plus redoutée”. [25] : 162–163 [114] : 263 Ils étaient particulièrement enclins à craindre la victoire iranienne après que l’ayatollah Khomeiny ait déclaré que les monarchies étaient illégitimes et une forme de gouvernement non islamique. [87] La déclaration de Khomeiny a été largement reçue comme un appel à renverser les monarchies du Golfe. [87] Les journalistes John Bulloch et Harvey Morris ont écrit :

La virulente campagne iranienne, qui à son apogée semblait faire du renversement du régime saoudien un objectif de guerre au même titre que la défaite de l’Irak, a eu un effet sur le Royaume [d’Arabie saoudite], mais pas sur celui que les Iraniens voulait : au lieu de devenir plus conciliants, les Saoudiens sont devenus plus durs, plus sûrs d’eux et moins enclins à rechercher des compromis. [25] : 163

L’Arabie saoudite fournirait à l’Irak 1 milliard de dollars par mois à partir de la mi-1982. [25] : 160

Saddam Hussein en 1982

Saddam Hussein en 1982

L’Irak a également commencé à recevoir le soutien des États-Unis et des pays d’Europe occidentale. Saddam a reçu un soutien diplomatique, monétaire et militaire des États-Unis, y compris des prêts massifs, une influence politique et des renseignements sur les déploiements iraniens recueillis par les satellites espions américains. [146] Les Irakiens se sont fortement appuyés sur les images satellite et les avions radar américains pour détecter les mouvements de troupes iraniennes, et ils ont permis à l’Irak de déplacer des troupes sur le site avant la bataille. [147]

Avec le succès de l’Iran sur le champ de bataille, les États-Unis ont accru leur soutien au gouvernement irakien, fournissant des renseignements, une aide économique et des équipements et véhicules à double usage , ainsi que la normalisation de leurs relations intergouvernementales (qui avaient été rompues lors des Six Jours de 1967). guerre ). [146] Le président Ronald Reagan a décidé que les États-Unis “ne pouvaient pas se permettre de permettre à l’Irak de perdre la guerre contre l’Iran”, et que les États-Unis “feraient tout ce qui était nécessaire pour empêcher l’Irak de perdre”. [148]En mars 1982, Reagan a signé le mémorandum d’étude sur la sécurité nationale (NSSM) 4-82 – cherchant “un examen de la politique américaine envers le Moyen-Orient” – et en juin, Reagan a signé une directive sur la décision de sécurité nationale (NSDD) co-écrite par le responsable du NSC, Howard . Teicher , qui a déterminé : “Les États-Unis ne pouvaient pas se permettre de laisser l’Irak perdre la guerre au profit de l’Iran.” [149] [150]

En 1982, Reagan a retiré l’Irak de la liste des pays « soutenant le terrorisme » et a vendu des armes telles que des obusiers à l’Irak via la Jordanie. [146] La France a vendu à l’Irak des millions de dollars d’armes, dont des hélicoptères Gazelle , des chasseurs Mirage F-1 et des missiles Exocet . Les États-Unis et l’Allemagne de l’Ouest ont vendu à l’Irak des pesticides et des poisons à double usage qui seraient utilisés pour créer des armes chimiques [146] et d’autres armes, telles que des missiles Roland . [ citation nécessaire ]

Dans le même temps, l’Union soviétique, en colère contre l’Iran pour avoir purgé et détruit le parti communiste Tudeh , a envoyé d’importantes cargaisons d’armes en Irak. L’armée de l’air irakienne a été reconstituée avec des avions de combat soviétiques, chinois et français et des hélicoptères d’attaque / de transport. L’Irak a également reconstitué ses stocks d’armes légères et d’armes antichars telles que des AK-47 et des grenades propulsées par fusée de ses partisans. Les forces de chars épuisées ont été reconstituées avec davantage de chars soviétiques et chinois, et les Irakiens ont été revigorés face à l’assaut iranien à venir. L’Iran était dépeint comme l’agresseur et serait considéré comme tel jusqu’à la guerre du golfe Persique de 1990-1991, lorsque l’Irak serait condamné. [ citation nécessaire ]

L’Iran n’avait pas l’argent pour acheter des armes dans la même mesure que l’Irak. Ils comptaient sur la Chine, la Corée du Nord , la Libye , la Syrie et le Japon pour tout fournir, des armes et des munitions aux équipements logistiques et d’ingénierie. [151]

Proposition de cessez-le-feu

Le 20 juin 1982, Saddam a annoncé qu’il voulait demander la paix et a proposé un cessez-le-feu immédiat et un retrait du territoire iranien dans les deux semaines. [152] Khomeiny a répondu en disant que la guerre ne se terminerait pas tant qu’un nouveau gouvernement ne serait pas installé en Irak et que les réparations n’auraient pas été payées. [153] Il a proclamé que l’Iran envahirait l’Irak et ne s’arrêterait pas tant que le régime Baas ne serait pas remplacé par une république islamique . [87] [144] L’Iran a soutenu un gouvernement en exil pour l’Irak, le Conseil suprême de la révolution islamique en Irak , dirigé par le religieux irakien exilé Mohammad Baqer al-Hakim, qui se consacrait au renversement du parti Baas. Ils ont recruté des prisonniers de guerre, des dissidents, des exilés et des chiites pour rejoindre la brigade Badr , la branche militaire de l’organisation. [84]

La décision d’envahir l’Irak a été prise après de nombreux débats au sein du gouvernement iranien. [87] Une faction, comprenant le Premier ministre Mir-Hossein Mousavi , le ministre des Affaires étrangères Ali Akbar Velayati , le président Ali Khamenei , le chef d’état-major de l’armée, le général Ali Sayad Shirazi, ainsi que le général de division Qasem-Ali Zahirnejad, voulait accepter le cessez-le-feu, car la plupart du sol iranien avait été reconquis. [87] En particulier, le général Shirazi et Zahirnejad étaient tous deux opposés à l’invasion de l’Irak pour des raisons logistiques et ont déclaré qu’ils envisageraient de démissionner si “des personnes non qualifiées continuaient à se mêler de la conduite de la guerre”. [87] : 38 Du point de vue opposé , il y avait une faction radicale dirigée par les religieux du Conseil suprême de la défense , dont le chef était le président politiquement puissant du Majlis , Akbar Hashemi Rafsandjani . [87]

L’Iran espérait également que leurs attaques déclencheraient une révolte contre le régime de Saddam par la population chiite et kurde d’Irak, entraînant peut-être sa chute. Ils ont réussi à le faire avec la population kurde, mais pas avec les chiites. [84] L’Iran avait capturé de grandes quantités d’équipement irakien (suffisamment pour créer plusieurs bataillons de chars, l’Iran disposait à nouveau de 1 000 chars) et avait également réussi à se procurer clandestinement des pièces de rechange. [107]

Lors d’une réunion du cabinet à Bagdad, le ministre de la Santé de Riyad Ibrahim Hussein a suggéré que Saddam pourrait démissionner temporairement afin d’amener l’Iran vers un cessez-le-feu, puis qu’il reviendrait ensuite au pouvoir. [25] : 147 Saddam, ennuyé, a demandé si quelqu’un d’autre dans le Cabinet était d’accord avec l’idée du ministre de la Santé. Quand personne n’a levé la main pour le soutenir, il a escorté Riyadh Hussein dans la pièce voisine, a fermé la porte et lui a tiré dessus avec son pistolet. [25] : 147 Saddam retourna dans la salle et poursuivit sa réunion. [ citation nécessaire ]

L’Iran envahit l’Irak Tactiques irakiennes contre l’invasion iranienne

Une déclaration d’avertissement émise par le gouvernement irakien afin d’avertir les troupes iraniennes dans la guerre Iran-Irak. La déclaration dit : “Hé Iraniens ! Personne n’a été opprimé dans le pays où Ali ibn Abi Ṭālib, Husayn ibn Ali et Abbas ibn Ali sont enterrés. L’Irak a sans aucun doute été un pays honorable. Tous les réfugiés sont précieux. Quiconque veut vivre en exil peut choisir librement l’Irak. Nous, les Fils de l’Irak, avons tendu une embuscade aux agresseurs étrangers. Les ennemis qui prévoient d’attaquer l’Irak seront défavorisés par Dieu dans ce monde et dans l’au-delà. Faites attention d’attaquer l’Irak et Ali ibn Abi Ṭālib ! Si vous vous rendez, vous pourriez être en paix.”

Une déclaration d’avertissement émise par le gouvernement irakien afin d’avertir les troupes iraniennes dans la guerre Iran-Irak. La déclaration dit : “Hé Iraniens ! Personne n’a été opprimé dans le pays où Ali ibn Abi Ṭālib, Husayn ibn Ali et Abbas ibn Ali sont enterrés. L’Irak a sans aucun doute été un pays honorable. Tous les réfugiés sont précieux. Quiconque veut vivre en exil peut choisir librement l’Irak. Nous, les Fils de l’Irak, avons tendu une embuscade aux agresseurs étrangers. Les ennemis qui prévoient d’attaquer l’Irak seront défavorisés par Dieu dans ce monde et dans l’au-delà. Faites attention d’attaquer l’Irak et Ali ibn Abi Ṭālib ! Si vous vous rendez, vous pourriez être en paix.”

Pour l’essentiel, l’Irak est resté sur la défensive pendant les cinq années suivantes, incapable et refusant de lancer des offensives majeures, tandis que l’Iran a lancé plus de 70 offensives. La stratégie de l’Irak est passée de la détention de territoires en Iran à la privation de l’Iran de tout gain majeur en Irak (ainsi qu’à la conservation de territoires contestés le long de la frontière). [85] Saddam a commencé une politique de guerre totale , orientant la majeure partie de son pays vers la défense contre l’Iran. En 1988, l’Irak dépensait 40 à 75 % de son PIB en équipement militaire. [154] Saddam avait également plus que doublé la taille de l’armée irakienne, passant de 200 000 soldats (12 divisions et trois brigades indépendantes) à 500 000 (23 divisions et neuf brigades). [87]L’Irak a également commencé à lancer des raids aériens contre les villes frontalières iraniennes, augmentant considérablement la pratique en 1984. À la fin de 1982, l’Irak avait été réapprovisionné en nouveau matériel soviétique et chinois , et la guerre terrestre est entrée dans une nouvelle phase. L’Irak a utilisé des chars T-55, T-62 et T-72 nouvellement acquis (ainsi que des copies chinoises), des lance-roquettes BM-21 montés sur camion et des hélicoptères de combat Mi-24 pour préparer une défense à trois lignes de type soviétique, rempli d’obstacles tels que des barbelés, des champs de mines, des positions fortifiées et des bunkers. Le Combat Engineer Corps a construit des ponts à travers les obstacles d’eau, posé des champs de mines, érigé des revêtements en terre, creusé des tranchées, construit des nids de mitrailleuses et préparé de nouvelles lignes de défense et fortifications. [85] : 2

L’Irak a commencé à se concentrer sur l’utilisation de la défense en profondeur pour vaincre les Iraniens. [107] L’Irak a créé plusieurs lignes de défense statiques pour saigner les Iraniens par leur taille. [107] Face à une grande attaque iranienne, où des vagues humaines envahiraient les défenses d’infanterie retranchées vers l’avant de l’Irak, les Irakiens se retireraient souvent, mais leurs défenses statiques saigneraient les Iraniens et les canaliseraient dans certaines directions, les attirant dans des pièges ou des poches. Les attaques aériennes et d’artillerie irakiennes immobiliseraient alors les Iraniens, tandis que les chars et les attaques d’infanterie mécanisée utilisant la guerre mobile les repousseraient. [147]Parfois, les Irakiens lançaient des “attaques de sondage” dans les lignes iraniennes pour les inciter à lancer leurs attaques plus tôt. Alors que les attaques iraniennes par vagues humaines ont réussi contre les forces irakiennes enfouies au Khouzistan, elles ont eu du mal à percer la défense irakienne dans les lignes de profondeur. [84] L’Irak avait un avantage logistique dans sa défense : le front était situé à proximité des principales bases et dépôts d’armes irakiens, permettant à leur armée d’être efficacement approvisionnée. [114] : 260, 265 En revanche, le front en Iran était à une distance considérable des principales bases iraniennes et des dépôts d’armes, et à ce titre, les troupes et les fournitures iraniennes devaient traverser des chaînes de montagnes avant d’arriver au front. [114] : 260

De plus, la puissance militaire de l’Iran a été affaiblie une fois de plus par de grandes purges en 1982, résultant d’une autre soi-disant tentative de coup d’État. [155]

Opération Ramadan (première bataille de Bassorah)

Les généraux iraniens voulaient lancer une attaque totale contre Bagdad et s’en emparer avant que la pénurie d’armes ne continue de se manifester davantage. Au lieu de cela, cela a été rejeté comme étant irréalisable [144] et la décision a été prise de capturer une région de l’Irak après l’autre dans l’espoir qu’une série de coups portés avant tout par le Corps des gardiens de la révolution forcerait une solution politique à la guerre ( y compris l’Irak se retirant complètement des territoires contestés le long de la frontière). [144]

Les Iraniens ont planifié leur attaque dans le sud de l’Irak, près de Bassorah. [87] Appelée Opération Ramadan , elle impliquait plus de 180 000 soldats des deux côtés et était l’une des plus grandes batailles terrestres depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale . [85] : 3 La stratégie iranienne dictait qu’ils lancent leur attaque primaire sur le point le plus faible des lignes irakiennes ; cependant, les Irakiens ont été informés des plans de bataille de l’Iran et ont déplacé toutes leurs forces vers la zone que les Iraniens prévoyaient d’attaquer. [143] Les Irakiens étaient équipés de gaz lacrymogènes à utiliser contre l’ennemi, ce qui serait la première utilisation majeure de la guerre chimique pendant le conflit, jetant toute une division d’attaque dans le chaos. [155]

95 000 enfants soldats iraniens ont été tués pendant la guerre Iran-Irak, pour la plupart âgés de 16 à 17 ans, avec quelques-uns plus jeunes. [156] [157]

95 000 enfants soldats iraniens ont été tués pendant la guerre Iran-Irak, pour la plupart âgés de 16 à 17 ans, avec quelques-uns plus jeunes. [156] [157]

Plus de 100 000 Gardiens de la révolution et forces volontaires Basij ont chargé vers les lignes irakiennes. [87] Les troupes irakiennes s’étaient retranchées dans de redoutables défenses et avaient mis en place un réseau de bunkers et de positions d’artillerie. [87] Les Basij ont utilisé des vagues humaines, et ont même été utilisés pour nettoyer physiquement les champs de mines irakiens et permettre aux gardiens de la révolution d’avancer. [87] Les combattants se sont rapprochés si près les uns des autres que les Iraniens ont pu monter à bord des chars irakiens et lancer des grenades à l’intérieur des coques. Au huitième jour, les Iraniens avaient gagné 16 km (9,9 mi) à l’intérieur de l’Irak et avaient emprunté plusieurs chaussées. Les gardiens de la révolution iraniens ont également utilisé les chars T-55 qu’ils avaient capturés lors de batailles précédentes. [107]

Cependant, les attaques se sont arrêtées et les Iraniens se sont tournés vers des mesures défensives. Voyant cela, l’Irak a utilisé ses hélicoptères Mi-25 , ainsi que des hélicoptères Gazelle armés d’ Euromissile HOT , contre des colonnes d’infanterie mécanisée et de chars iraniens. Ces équipes d’hélicoptères “chasseurs-tueurs”, constituées avec l’aide de conseillers est-allemands , s’avèrent très coûteuses pour les Iraniens. Des combats aériens ont eu lieu entre des MiG irakiens et des F-4 Phantoms iraniens. [155]

Le 16 juillet, l’Iran tente à nouveau plus au nord et parvient à repousser les Irakiens. Cependant, à seulement 13 km (8,1 mi) de Bassorah, les forces iraniennes mal équipées étaient encerclées sur trois côtés par des Irakiens dotés d’armes lourdes. Certains ont été capturés, tandis que beaucoup ont été tués. Seule une attaque de dernière minute par des hélicoptères iraniens AH-1 Cobra a empêché les Irakiens de mettre en déroute les Iraniens. [143] Trois autres attaques similaires se sont produites autour de la zone routière Khorramshahr-Bagdad vers la fin du mois, mais aucune n’a été significativement couronnée de succès. [107]L’Irak avait concentré trois divisions blindées, les 3e, 9e et 10e, comme force de contre-attaque pour attaquer toutes les pénétrations. Ils ont réussi à vaincre les percées iraniennes, mais ont subi de lourdes pertes. La 9e division blindée en particulier a dû être dissoute et n’a jamais été réformée. Le nombre total de victimes avait augmenté pour inclure 80 000 soldats et civils. 400 chars et véhicules blindés iraniens ont été détruits ou abandonnés, tandis que l’Irak a perdu pas moins de 370 chars. [158] [159]

Combattre pendant le reste de 1982

Après l’échec de l’Iran dans l’opération Ramadan, ils n’ont mené que quelques petites attaques. L’Iran a lancé deux offensives limitées visant à récupérer les collines de Sumar et à isoler la poche irakienne de Naft Shahr à la frontière internationale, qui faisaient toutes deux partie des territoires contestés toujours sous occupation irakienne. Ils visaient alors à s’emparer de la ville frontalière irakienne de Mandali . [143] Ils prévoyaient de prendre les Irakiens par surprise en utilisant des miliciens Basij, des hélicoptères de l’armée et certaines forces blindées, puis d’étendre leurs défenses et éventuellement de les percer pour ouvrir une route vers Bagdad pour une exploitation future. [143] Au cours de l’opération Muslim ibn Aqil (du 1er au 7 octobre), [note 7] l’Iran a récupéré 150 km2 (58 milles carrés) de territoire contesté à cheval sur la frontière internationale et a atteint la périphérie de Mandali avant d’être arrêté par des hélicoptères irakiens et des attaques blindées. [122] [143] Au cours de l’opération Muharram (du 1er au 21 novembre), [note 8] les Iraniens ont capturé une partie du champ pétrolifère de Bayat à l’aide de leurs avions de chasse et hélicoptères, détruisant 105 chars irakiens, 70 APC et 7 avions avec peu de pertes. Ils ont failli franchir les lignes irakiennes mais n’ont pas réussi à capturer Mandali après que les Irakiens aient envoyé des renforts, y compris de tout nouveaux chars T-72 , qui possédaient un blindage qui ne pouvait pas être percé de face par les missiles TOW iraniens .[143] L’avancée iranienne a également été entravée par de fortes pluies. 3 500 Irakiens et un nombre inconnu d’Iraniens sont morts, avec seulement des gains mineurs pour l’Iran. [143]

1983-1984 : impasse stratégique et guerre d’usure

Gains de terrain les plus éloignés

Gains de terrain les plus éloignés

Après l’échec des offensives d’été de 1982, l’Iran croyait qu’un effort majeur sur toute la largeur du front donnerait la victoire. Au cours de 1983, les Iraniens ont lancé cinq assauts majeurs le long du front, bien qu’aucun n’ait obtenu de succès substantiel, alors que les Iraniens organisaient des attaques plus massives de «vague humaine». [87] À cette époque, on estimait que pas plus de 70 avions de combat iraniens étaient encore opérationnels à un moment donné ; L’Iran avait ses propres installations de réparation d’hélicoptères, héritées d’avant la révolution, et utilisait donc souvent des hélicoptères pour un appui aérien rapproché. [143] [161] Les pilotes de chasse iraniens avaient une formation supérieure à celle de leurs homologues irakiens (car la plupart avaient reçu une formation d’officiers américains avant la révolution de 1979) [162] et continuerait à dominer au combat. [163] Cependant, les pénuries d’avions, la taille du territoire/espace aérien défendu et les renseignements américains fournis à l’Irak ont permis aux Irakiens d’exploiter les lacunes de l’espace aérien iranien. Les campagnes aériennes irakiennes ont rencontré peu d’opposition, frappant plus de la moitié de l’Iran, car les Irakiens ont pu acquérir la supériorité aérienne vers la fin de la guerre. [164]

Opération avant l’aube

Dans l’opération Before the Dawn , lancée le 6 février 1983, les Iraniens ont déplacé l’attention des secteurs sud vers le centre et le nord. Employant 200 000 soldats des Gardiens de la révolution de la “dernière réserve”, l’Iran a attaqué le long d’un tronçon de 40 km (25 mi) près d’al-Amarah, en Irak , à environ 200 km (120 mi) au sud-est de Bagdad, dans une tentative d’atteindre les autoroutes reliant le nord et le sud. Irak. L’attaque a été bloquée par 60 km (37 mi) d’escarpements vallonnés, de forêts et de torrents de rivière recouvrant le chemin d’al-Amarah, mais les Irakiens n’ont pas pu forcer les Iraniens à reculer. L’Iran a dirigé l’artillerie sur Bassorah, Al Amarah et Mandali . [161]

Les Iraniens ont subi un grand nombre de pertes en déminant les champs de mines et en brisant les mines antichars irakiennes, que les ingénieurs irakiens n’ont pas été en mesure de remplacer. Après cette bataille, l’Iran a réduit son utilisation des attaques par vagues humaines, même si elles sont restées une tactique clé pendant la guerre. [161]

D’autres attaques iraniennes ont été lancées dans le secteur centre-nord de Mandali-Bagdad en avril 1983, mais ont été repoussées par des divisions mécanisées et d’infanterie irakiennes. Les pertes étaient élevées et à la fin de 1983, environ 120 000 Iraniens et 60 000 Irakiens avaient été tués. L’Iran, cependant, avait l’avantage dans la guerre d’usure ; en 1983, l’Iran avait une population estimée à 43,6 millions contre 14,8 millions pour l’Irak, et l’écart a continué de croître tout au long de la guerre. [85] [165] [166] : 2

Opérations de l’aube

Du début de 1983 à 1984, l’Iran a lancé une série de quatre opérations Valfajr (Dawn) (qui ont finalement été numérotées à 10). Au cours de l’opération Dawn-1 , début février 1983, 50 000 soldats iraniens ont attaqué à l’ouest de Dezful et ont été confrontés à 55 000 soldats irakiens. L’objectif iranien était de couper la route de Bassorah à Bagdad dans le secteur central. Les Irakiens ont effectué 150 sorties aériennes contre les Iraniens et ont même bombardé Dezful, Ahvaz et Khorramshahr en représailles. La contre-attaque irakienne a été interrompue par la 92e division blindée iranienne. [161]

Prisonniers de guerre iraniens en 1983 près de Tikrit , Irak

Prisonniers de guerre iraniens en 1983 près de Tikrit , Irak

Lors de l’opération Aube-2 , les Iraniens ont dirigé les opérations d’insurrection par procuration en avril 1983 en soutenant les Kurdes dans le nord. Avec le soutien des Kurdes, les Iraniens ont attaqué le 23 juillet 1983, capturant la ville irakienne de Haj Omran et la maintenant contre une contre-offensive irakienne au gaz toxique. [ citation nécessaire ] Cette opération a incité l’Irak à mener plus tard des attaques chimiques aveugles contre les Kurdes. [161] Les Iraniens ont tenté d’exploiter davantage les activités dans le nord le 30 juillet 1983, lors de l’opération Dawn-3 . L’Iran a vu une opportunité de balayer les forces irakiennes contrôlant les routes entre les villes frontalières des montagnes iraniennes de Mehran, Dehloran etÉlam . l’Irak a lancé des frappes aériennes et équipé des hélicoptères d’attaque d’ ogives chimiques ; bien qu’inefficace, il a démontré à la fois l’état-major irakien et l’intérêt croissant de Saddam pour l’utilisation d’armes chimiques. En fin de compte, 17 000 avaient été tués des deux côtés, [ une clarification nécessaire ] sans gain pour aucun des deux pays. [161]

L’ opération Dawn-4 en septembre 1983 s’est concentrée sur le secteur nord du Kurdistan iranien. Trois divisions régulières iraniennes, les Gardiens de la révolution et des éléments du Parti démocratique du Kurdistan (PDK) se sont rassemblés à Marivan et Sardasht dans le but de menacer la grande ville irakienne Suleimaniyah . La stratégie de l’Iran était de faire pression sur les tribus kurdes pour qu’elles occupent la vallée de Banjuin, qui se trouvait à moins de 45 km (28 mi) de Suleimaniyah et à 140 km (87 mi) des champs pétrolifères de Kirkouk . Pour endiguer la marée, l’Irak a déployé des Mi-8des hélicoptères d’attaque équipés d’armes chimiques et ont exécuté 120 sorties contre la force iranienne, qui les a arrêtés à 15 km (9,3 mi) en territoire irakien. 5 000 Iraniens et 2 500 Irakiens sont morts. [161] L’Iran a gagné 110 km 2 (42 milles carrés) de son territoire dans le nord, a gagné 15 km 2 (5,8 milles carrés) de terres irakiennes et a capturé 1 800 prisonniers irakiens tandis que l’Irak a abandonné de grandes quantités d’armes et de matériel de guerre précieux. Sur le terrain. L’Irak a répondu à ces pertes en tirant une série de missiles SCUD-B sur les villes de Dezful, Masjid Soleiman et Behbehan.. L’utilisation de l’artillerie par l’Iran contre Bassorah alors que les batailles dans le nord faisaient rage a créé de multiples fronts, qui ont effectivement confondu et épuisé l’Irak. [161]

Le changement de tactique de l’Iran

Auparavant, les Iraniens étaient plus nombreux que les Irakiens sur le champ de bataille, mais l’Irak a élargi son projet militaire (poursuivant une politique de guerre totale) et, en 1984, les armées étaient de taille égale. En 1986, l’Irak comptait deux fois plus de soldats que l’Iran. En 1988, l’Irak compterait 1 million de soldats, ce qui en ferait la quatrième plus grande armée du monde. Certains de leurs équipements, tels que les chars, étaient plus nombreux que ceux des Iraniens d’au moins cinq contre un. Les commandants iraniens, cependant, sont restés plus habiles sur le plan tactique. [107]

enfant soldat iranien

enfant soldat iranien

Après les opérations de l’aube, l’Iran a tenté de changer de tactique. Face à l’augmentation de la défense irakienne en profondeur, ainsi qu’à l’augmentation des armements et des effectifs, l’Iran ne pouvait plus compter sur de simples attaques par vagues humaines. [120] Les offensives iraniennes sont devenues plus complexes et ont impliqué une vaste guerre de manœuvre utilisant principalement de l’infanterie légère. L’Iran a lancé des offensives fréquentes, et parfois plus petites, pour gagner lentement du terrain et épuiser les Irakiens par attrition. [118] Ils voulaient conduire l’Irak à l’échec économique en gaspillant de l’argent en armes et en mobilisation de guerre, et épuiser leur plus petite population en les saignant à blanc, en plus de créer une insurrection anti-gouvernementale (ils ont réussi au Kurdistan, mais pas au sud). Irak).[84] [118] [155] L’Iran a également soutenu leurs attaques avec des armes lourdes lorsque cela était possible et avec une meilleure planification (bien que le poids des batailles revienne toujours à l’infanterie). L’armée et les gardiens de la révolution ont mieux travaillé ensemble à mesure que leurs tactiques s’amélioraient. [84] Les attaques par vagues humaines sont devenues moins fréquentes (bien qu’elles soient toujours utilisées). [137] Pour nier l’avantage irakien de la défense en profondeur, des positions statiques et de la puissance de feu lourde, l’Iran a commencé à se concentrer sur les combats dans les zones où les Irakiens ne pouvaient pas utiliser leurs armes lourdes, comme les marais, les vallées et les montagnes, et en utilisant fréquemment tactiques d’infiltration. [137]