Élection présidentielle américaine de 2016

L’ élection présidentielle américaine de 2016 était la 58e élection présidentielle quadriennale , tenue le mardi 8 novembre 2016. Le ticket républicain de l’homme d’affaires Donald Trump et du gouverneur de l’Indiana Mike Pence a battu le ticket démocrate de l’ancienne secrétaire d’État Hillary Clinton et sénateur américain de Virginie Tim Kaine , dans ce qui était considéré comme l’un des plus grands bouleversements de l’histoire américaine. Trump a pris ses fonctions de 45e président et Pence de 48e vice-président, le 20 janvier 2017. Il s’agissait de la cinquième et dernière élection présidentielle au cours de laquelle le candidat vainqueur a perdu le vote populaire . [2] [3]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

538 membres du Collège |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sondages d’opinion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S’avérer | 55,7 % [1] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Selon le vingt-deuxième amendement à la Constitution des États-Unis , le président sortant Barack Obama n’était pas éligible pour briguer un troisième mandat. Clinton a vaincu le sénateur socialiste démocrate autoproclamé Bernie Sanders lors de la primaire démocrate et est devenue la première femme candidate à la présidence d’un grand parti politique américain. Trump est devenu le favori de son parti parmi un large éventail de candidats à la primaire républicaine , battant le sénateur Ted Cruz , le sénateur Marco Rubio et le gouverneur de l’Ohio John Kasich , entre autres candidats. LeLe Parti Libertaire a nommé l’ancien Gouverneur du Nouveau-Mexique Gary Johnson , et le Parti Vert a nommé Jill Stein . La campagne nationaliste populiste de droite de Trump , qui promettait de « rendre l’Amérique encore plus belle » et s’opposait au politiquement correct , à l’immigration illégale et à de nombreux accords de libre-échange avec les États-Unis [4] a bénéficié d’une large couverture médiatique gratuite en raison des commentaires incendiaires de Trump. [5] [6] Clinton a souligné sa vaste expérience politique, a dénoncé Trump et nombre de ses partisans comme un “panier de déplorables “, fanatiques et extrémistes, et a préconisé l’expansion des politiques du président Obama ; les droits raciaux , LGBT et des femmes ; et le capitalisme inclusif . [7]

Le ton de la campagne électorale générale a été largement qualifié de diviseur et négatif. [8] [9] [10] Trump a fait face à une controverse sur ses opinions sur la race et l’immigration , des incidents de violence contre des manifestants lors de ses rassemblements, [11] [12] [13] et de nombreuses allégations d’inconduite sexuelle, y compris la bande Access Hollywood . La popularité et l’image publique de Clinton ont été ternies par des préoccupations concernant son éthique et sa fiabilité, [14] et une controverse et une enquête ultérieure du FBI concernant son utilisation abusive d’un serveur de messagerie privé.en tant que secrétaire d’État, qui a reçu plus de couverture médiatique que tout autre sujet pendant la campagne. [15] [16]

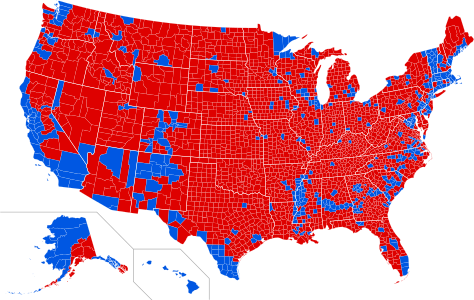

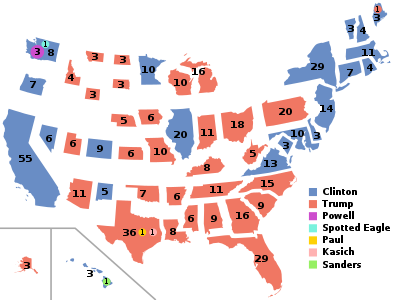

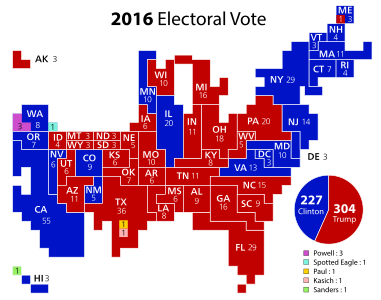

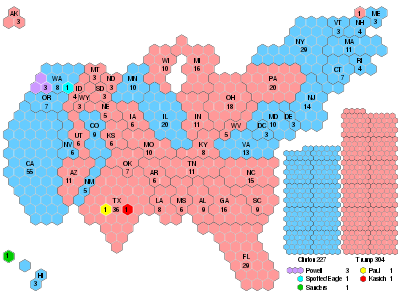

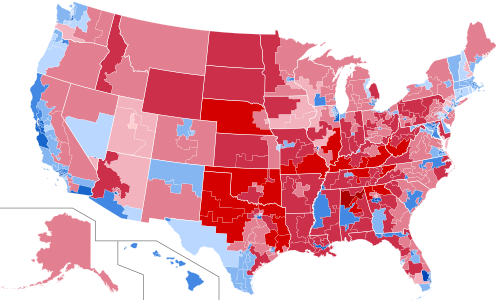

Clinton était en tête dans presque tous les sondages nationaux et dans les États oscillants, certains modèles prédictifs donnant à Clinton plus de 90 % de chances de gagner. [17] [18] Le jour des élections, Trump a surperformé ses sondages, remportant plusieurs États clés, tout en perdant le vote populaire de 2,87 millions de voix. [19] Trump a obtenu la majorité au Collège électoral et a remporté des victoires bouleversées dans la région charnière de Rust Belt . En fin de compte, Trump a reçu 304 votes électoraux et Clinton 227, alors que deux électeurs infidèles ont fait défection de Trump et cinq de Clinton. Trump a été le premier président sans service public ni expérience militaire .

Trump est devenu le premier et le seul républicain à remporter les États de Pennsylvanie et du Michigan depuis 1988, et le premier et le seul à remporter le Wisconsin depuis 1984. C’était la première fois depuis 1988 que le républicain remportait le deuxième district du Congrès du Maine, et avec la victoire de Trump en En Pennsylvanie, c’était la première fois depuis 2000 que le candidat républicain remportait un État du Nord-Est, lorsqu’il remportait le New Hampshire. Cela reste la seule élection depuis 1988, au cours de laquelle un républicain a remporté plus de 300 voix électorales. C’est la seule élection depuis 2000 où aucun candidat n’a obtenu la majorité du vote populaire. Avec près de 6% du vote populaire collectivement, cela constitue le meilleur tiers parti depuis les élections de 1996.

Arrière-plan

Le titulaire en 2016, Barack Obama . Son deuxième mandat a expiré à midi le 20 janvier 2017.

Le titulaire en 2016, Barack Obama . Son deuxième mandat a expiré à midi le 20 janvier 2017.

L’article 2 de la Constitution des États-Unis stipule que le président et le vice-président des États-Unis doivent être des citoyens nés aux États-Unis, âgés d’au moins 35 ans et résidents des États-Unis depuis au moins 14 ans. [20] Les candidats à la présidence recherchent généralement la nomination de l’un des partis politiques, auquel cas chaque parti conçoit une méthode (telle qu’une élection primaire ) pour choisir le candidat que le parti juge le plus apte à se présenter pour le poste. Traditionnellement, les élections primaires sont des élections indirectesoù les électeurs votent pour une liste de délégués du parti promis à un candidat particulier. Les délégués du parti désignent ensuite officiellement un candidat pour se présenter au nom du parti. L’élection générale de novembre est également une élection indirecte, où les électeurs votent pour une liste de membres du collège électoral ; ces électeurs élisent à leur tour directement le président et le vice-président. [21]

Le président Barack Obama , un démocrate et ancien sénateur américain de l’Illinois , n’était pas éligible pour se faire réélire pour un troisième mandat en raison des restrictions imposées par les limites du mandat présidentiel américain établies par le vingt-deuxième amendement ; conformément à l’article 1 du vingtième amendement , son mandat a expiré à midi , heure normale de l’Est, le 20 janvier 2017. [22] [23]

Processus principal

Les partis démocrate et républicain, ainsi que des tiers tels que les partis vert et libertaire, ont organisé une série d’ élections primaires présidentielles et de caucus qui ont eu lieu entre février et juin 2016, échelonnés entre les 50 États, le district de Columbia et territoires américains . Ce processus de nomination était également une élection indirecte, où les électeurs votaient pour une liste de délégués à la convention de nomination d’un parti politique , qui à leur tour élisaient le candidat présidentiel de leur parti.

Les spéculations sur la campagne de 2016 ont commencé presque immédiatement après la campagne de 2012, le magazine new-yorkais déclarant que la course avait commencé dans un article publié le 8 novembre, deux jours après les élections de 2012. [24] Le même jour, Politico a publié un article prédisant que les élections générales de 2016 auraient lieu entre Clinton et l’ancien gouverneur de Floride Jeb Bush , tandis qu’un article du New York Times nommait le gouverneur du New Jersey Chris Christie et le sénateur Cory Booker du New Jersey . comme candidats potentiels. [25] [26]

Candidatures

parti républicain

Primaires

Avec dix-sept principaux candidats entrant dans la course, à commencer par Ted Cruz le 23 mars 2015, il s’agissait du plus grand champ de primaires présidentielles pour tous les partis politiques de l’histoire américaine, [27] avant d’être dépassé par les primaires présidentielles démocrates de 2020. [28]

Avant les caucus de l’Iowa le 1er février 2016, Perry, Walker, Jindal, Graham et Pataki se sont retirés en raison du faible nombre de sondages. Bien qu’il ait mené de nombreux sondages dans l’Iowa, Trump est arrivé deuxième derrière Cruz, après quoi Huckabee, Paul et Santorum se sont retirés en raison de mauvaises performances aux urnes. Suite à une victoire importante de Trump dans la primaire du New Hampshire , Christie, Fiorina et Gilmore ont abandonné la course. Bush a emboîté le pas après avoir marqué la quatrième place devant Trump, Rubio et Cruz en Caroline du Sud . Le 1er mars 2016, le premier des quatre ” Super Tuesday” primaires, Rubio a remporté son premier concours dans le Minnesota, Cruz a remporté l’Alaska, l’Oklahoma et son État d’origine, le Texas, et Trump a remporté les sept autres États qui ont voté. À défaut de gagner du terrain, Carson a suspendu sa campagne quelques jours plus tard. [29 ] Le 15 mars 2016, le deuxième “Super Tuesday”, Kasich a remporté son seul concours dans son État d’origine, l’Ohio, et Trump a remporté cinq primaires, dont la Floride. Rubio a suspendu sa campagne après avoir perdu son État d’origine. [30]

Entre le 16 mars et le 3 mai 2016, seuls trois candidats sont restés en lice : Trump, Cruz et Kasich. Cruz a remporté le plus de délégués dans quatre concours occidentaux et dans le Wisconsin, gardant une voie crédible pour refuser à Trump la nomination au premier tour avec 1 237 délégués. Trump a ensuite augmenté son avance en remportant des victoires écrasantes à New York et dans cinq États du nord-est en avril, suivies d’une victoire décisive dans l’Indiana le 3 mai 2016, sécurisant les 57 délégués de l’État. Sans aucune autre chance de forcer une convention contestée , Cruz [31] et Kasich [32] ont suspendu leurs campagnes. Trump est resté le seul candidat actif et a été déclaré candidat républicain présumé par le président du Comité national républicainReince Priebus le soir du 3 mai 2016. [33]

Une étude de 2018 a révélé que la couverture médiatique de Trump avait conduit à un soutien public accru pour lui pendant les primaires. L’étude a montré que Trump avait reçu près de 2 milliards de dollars en médias libres, soit plus du double de tout autre candidat. Le politologue John M. Sides a fait valoir que la vague de sondages de Trump était “presque certainement” due à la couverture médiatique fréquente de sa campagne. Sides a conclu que “Trump monte en flèche dans les sondages parce que les médias se sont constamment concentrés sur lui depuis qu’il a annoncé sa candidature le 16 juin”. [34] Avant de décrocher la nomination républicaine, Trump a reçu peu de soutien des républicains de l’establishment. [35]

Nominés

Billet Parti républicain 2016 Billet Parti républicain 2016 |

|

|---|---|

| Donald Trump | Mike Pence |

| pour président | pour le vice-président |

|

|

| Président de l’organisation Trump (1971-2017) |

50e gouverneur de l’Indiana (2013-2017) |

| Campagne | |

|

Candidats

Les principaux candidats ont été déterminés par les différents médias sur la base d’un consensus commun. Les personnes suivantes ont été invitées à des débats télévisés sanctionnés en fonction de leurs cotes d’écoute.

Trump a reçu 14 010 177 votes au total à la primaire. Trump, Cruz, Rubio et Kasich ont chacun remporté au moins une primaire, Trump recevant le plus grand nombre de votes et Ted Cruz recevant le deuxième plus élevé.

| Les candidats de cette section sont triés par date inversée de retrait des primaires | |||||||

| Jean Kasich | Ted-Cruz | Marco Rubio | Ben Carson | Jeb Bush | Jim Gilmore | Carly Fiorina | Chris Christi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 69e gouverneur de l’Ohio (2011-2019) |

Sénateur américain du Texas (2013- présent ) |

Sénateur américain de Floride (2011- présent ) |

Réal. de neurochirurgie pédiatrique , hôpital Johns Hopkins (1984-2013) |

43e gouverneur de Floride (1999–2007) |

68e gouverneur de Virginie (1998–2002) |

PDG de Hewlett-Packard (1999–2005) |

55e gouverneur du New Jersey (2010-2018) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne |

| W : 4 mai 4 287 479 voix |

W : 3 mai 7 811 110 voix |

W : 15 mars 3 514 124 votes |

W : 4 mars 857 009 votes |

W : 20 février 286 634 votes |

W : 12 février 18 364 votes |

W : 10 février 40 577 votes |

W : 10 février 57 634 votes |

| [36] | [37] [38] [39] | [40] [41] [42] | [43] [44] [45] | [46] [47] | [48] [49] | [50] [51] | [52] [53] |

| Rand Paul | Rick Santorum | Mike Huckabee | Georges Pataki | Lindsey Graham | Bobby Jindal | Scott Walker | Rick Perry |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sénateur américain du Kentucky (2011- présent ) |

Sénateur américain de Pennsylvanie (1995–2007) |

44e gouverneur de l’Arkansas (1996–2007) |

53e gouverneur de New York (1995–2006) |

Sénateur américain de Caroline du Sud (2003- présent ) |

55e gouverneur de Louisiane (2008-2016) |

45e gouverneur du Wisconsin (2011-2019) |

47e gouverneur du Texas (2000-2015) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne |

| W : 3 février 66 781 votes |

W : 3 février 16 622 votes |

W : 1er février 51 436 votes |

W : 29 décembre 2015 2 036 voix |

W : 21 décembre 2015 5 666 voix |

W : 17 novembre 2015 222 voix |

W : 21 septembre 2015 1 vote écrit dans le New Hampshire |

W : 11 septembre 2015 1 vote écrit dans le New Hampshire |

| [54] [55] [56] | [57] [58] | [59] [60] | [61] | [62] [63] | [64] [65] | [66] [67] [68] | [68] [69] [70] |

Sélection vice-présidentielle

Trump a tourné son attention vers la sélection d’un colistier après être devenu le candidat présumé le 4 mai 2016. [71] À la mi-juin, Eli Stokols et Burgess Everett de Politico ont rapporté que la campagne Trump envisageait le gouverneur du New Jersey Chris Christie , ancien Le président de la Chambre Newt Gingrich de Géorgie , le sénateur Jeff Sessions de l’Alabama et la gouverneure de l’Oklahoma Mary Fallin . [72] Un rapport du 30 juin du Washington Post comprenait également les sénateurs Bob Corker du Tennessee, Richard Burrde Caroline du Nord , Tom Cotton de l’Arkansas, Joni Ernst de l’Iowa et le gouverneur de l’Indiana Mike Pence en tant qu’individus toujours considérés pour le billet. [73] Trump a également déclaré qu’il envisageait deux généraux militaires pour le poste, dont le lieutenant-général à la retraite Michael Flynn . [74]

En juillet 2016, il a été rapporté que Trump avait réduit sa liste de colistiers possibles à trois : Christie, Gingrich et Pence. [75]

Le 14 juillet 2016, plusieurs grands médias ont rapporté que Trump avait choisi Pence comme colistier. Trump a confirmé ces informations dans un message Twitter le 15 juillet 2016 et a officiellement fait l’annonce le lendemain à New York. [76] [77] Le 19 juillet, la deuxième nuit de la Convention nationale républicaine de 2016 , Pence a remporté la nomination républicaine à la vice-présidence par acclamation. [78]

Parti démocrate

Primaires

L’ancienne secrétaire d’État Hillary Clinton , qui a également siégé au Sénat américain et a été la première dame des États-Unis , est devenue la première démocrate sur le terrain à lancer officiellement une candidature majeure à la présidence avec une annonce le 12 avril 2015, via un message vidéo. [79] Alors que les sondages d’opinion à l’échelle nationale en 2015 indiquaient que Clinton était la favorite pour l’investiture présidentielle démocrate de 2016, elle a été confrontée à de sérieux défis de la part du sénateur indépendant Bernie Sanders du Vermont, [80] qui est devenu le deuxième candidat majeur lorsqu’il a officiellement annoncé le le 30 avril 2015, qu’il se présentait à l’investiture démocrate. [81]Les résultats des sondages de septembre 2015 indiquaient un rétrécissement de l’écart entre Clinton et Sanders. [80] [82] [83] Le 30 mai 2015, l’ancien gouverneur du Maryland Martin O’Malley était le troisième candidat majeur à entrer dans la course primaire démocrate, [84] suivi par l’ancien gouverneur indépendant et sénateur républicain de Rhode Island Lincoln Chafee le 3 juin 2015, [85] [86] l’ancien sénateur de Virginie Jim Webb le 2 juillet 2015, [87] et l’ancien professeur de droit de Harvard Lawrence Lessig le 6 septembre 2015. [88]

Le 20 octobre 2015, Webb a annoncé son retrait des primaires et a exploré une éventuelle course indépendante. [89] Le jour suivant, le vice-président Joe Biden a décidé de ne pas se présenter, mettant fin à des mois de spéculation, déclarant : « Bien que je ne sois pas candidat, je ne me tais pas. [90] [91] Le 23 octobre, Chafee s’est retiré, déclarant qu’il espérait “une fin aux guerres sans fin et le début d’une nouvelle ère pour les États-Unis et l’humanité.” [92] Le 2 novembre, après avoir échoué à se qualifier pour le deuxième débat sanctionné par le DNC après l’adoption d’un changement de règle annulant les sondages qui auparavant auraient pu nécessiter son inclusion dans le débat, Lessig s’est également retiré, rétrécissant le champ à Clinton, O’ Malley et Sanders. [93]

Le 1er février 2016, dans un concours extrêmement serré, Clinton a remporté les caucus de l’Iowa avec une marge de 0,2 point sur Sanders. Après avoir remporté aucun délégué dans l’Iowa, O’Malley s’est retiré de la course présidentielle ce jour-là. Le 9 février, Sanders a rebondi pour remporter la primaire du New Hampshire avec 60% des voix. Lors des deux autres concours de février, Clinton a remporté les caucus du Nevada avec 53% des voix et a remporté une victoire décisive à la primaire de Caroline du Sud avec 73% des voix. [94] [95] Le 1er mars, 11 États ont participé au premier des quatre ” Super Tuesday” primaires. Clinton a remporté l’Alabama, l’Arkansas, la Géorgie, le Massachusetts, le Tennessee, le Texas et la Virginie et 504 délégués promis, tandis que Sanders a remporté le Colorado , le Minnesota, l’Oklahoma et son État natal du Vermont et 340 délégués. Le week-end suivant, Sanders a remporté des victoires au Kansas , Nebraska , et Maine avec des marges de 15 à 30 points, tandis que Clinton a remporté la primaire de Louisiane avec 71% des voix. Le 8 mars, bien qu’il n’ait jamais eu d’avance dans la primaire du Michigan , Sanders a gagné avec une petite marge de 1,5 point et surpassant les sondages de plus de 19 points, tandis que Clinton a remporté 83 % des voix dans le Mississippi [96] .Le 15 mars, le deuxième “Super Tuesday”, Clinton a gagné en Floride , en Illinois , au Missouri , en Caroline du Nord et en Ohio . Entre le 22 mars et le 9 avril, Sanders a remporté six caucus dans l’Idaho , l’Utah , l’ Alaska , Hawaï , Washington et le Wyoming , ainsi que la primaire du Wisconsin , tandis que Clinton a remporté la primaire de l’Arizona . Le 19 avril, Clinton a remporté la primaire de New York avec 58 % des voix. Le 26 avril, lors du troisième “Super Tuesday” surnommé le “Primaire d’Acela”, elle a remporté des concours dans le Connecticut, Delaware , Maryland et Pennsylvanie , tandis que Sanders a gagné dans le Rhode Island . Au cours du mois de mai, Sanders a remporté une autre victoire surprise dans la primaire de l’Indiana [97] et a également gagné en Virginie-Occidentale et en Oregon , tandis que Clinton a remporté le caucus de Guam et la primaire du Kentucky (ainsi que des primaires non contraignantes au Nebraska et à Washington).

Les 4 et 5 juin, Clinton a remporté deux victoires dans le caucus des îles Vierges et la primaire de Porto Rico . Le 6 juin 2016, l ‘ Associated Press et NBC News ont rapporté que Clinton était devenue la candidate présumée après avoir atteint le nombre requis de délégués, y compris les délégués et superdélégués promis , pour obtenir la nomination, devenant ainsi la première femme à décrocher la nomination présidentielle de un grand parti politique américain. [98] Le 7 juin, Clinton a obtenu la majorité des délégués promis après avoir remporté les primaires en Californie , New Jersey , Nouveau-Mexique etDakota du Sud , tandis que Sanders n’a remporté que le Montana et le Dakota du Nord . Clinton a également remporté la primaire finale dans le district de Columbia le 14 juin. À l’issue du processus primaire, Clinton avait remporté 2 204 délégués promis (54% du total) attribués par les élections primaires et les caucus, tandis que Sanders avait remporté 1 847 ( 46 %). Sur les 714 délégués ou “superdélégués” non engagés qui devaient voter lors de la convention en juillet , Clinton a reçu l’approbation de 560 (78%), tandis que Sanders en a reçu 47 (7%). [99]

Bien que Sanders n’ait pas officiellement abandonné la course, il a annoncé le 16 juin 2016 que son objectif principal dans les mois à venir serait de travailler avec Clinton pour vaincre Trump aux élections générales. [100] Le 8 juillet, les personnes nommées de la campagne Clinton, de la campagne Sanders et du Comité national démocrate ont négocié une ébauche de la plate-forme du parti. [101] Le 12 juillet, Sanders a officiellement approuvé Clinton lors d’un rassemblement dans le New Hampshire dans lequel il est apparu avec elle. [102] Sanders a ensuite fait la une de 39 rassemblements électoraux au nom de Clinton dans 13 États clés. [103]

Nominés

Billet du Parti démocrate 2016 Billet du Parti démocrate 2016 |

|

|---|---|

| Hillary Clinton | Tim Kainé |

| pour président | pour le vice-président |

|

|

| 67e secrétaire d’État américain (2009-2013) |

Sénateur américain de Virginie (2013-présent) |

| Campagne | |

|

Candidats

Les candidats suivants ont été fréquemment interviewés par les principaux réseaux de diffusion et les chaînes d’information par câble ou ont été répertoriés dans des sondages nationaux publiés publiquement. Lessig a été invité à un forum, mais s’est retiré lorsque les règles ont été modifiées, ce qui l’a empêché de participer à des débats officiellement sanctionnés.

Clinton a reçu 16 849 779 voix à la primaire.

| Les candidats de cette rubrique sont triés par date d’abandon des primaires | ||||

| Bernie Sanders | Martin O’Malley | Laurent Lessig | Lincoln Chafé | Jim Webb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sénateur américain du Vermont (2007- présent ) |

61e gouverneur du Maryland (2007-2015) |

Professeur de droit à Harvard (2009-2016) |

74e gouverneur du Rhode Island (2011-2015) |

Sénateur américain de Virginie (2007-2013) |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne | Campagne |

| LN : 26 juillet 2016 13 167 848 voix |

W : 1er février 2016 110 423 voix |

W : 2 novembre 2015 4 votes écrits dans le New Hampshire |

W : 23 octobre 2015 0 votes |

W : 20 octobre 2015 2 votes écrits dans le New Hampshire |

| [104] | [105] [106] | [93] | [107] | [108] |

Sélection vice-présidentielle

En avril 2016, la campagne Clinton a commencé à dresser une liste de 15 à 20 personnes à examiner pour le poste de colistier, même si Sanders a continué à défier Clinton lors des primaires démocrates. [109] À la mi-juin, le Wall Street Journal a rapporté que la liste restreinte de Clinton comprenait le représentant Xavier Becerra de Californie, le sénateur Cory Booker du New Jersey , le sénateur Sherrod Brown de l’Ohio , le secrétaire au logement et au développement urbain Julián Castro du Texas , le maire de Los Angeles . Eric Garcetti de Californie , sénateurTim Kaine de Virginie , le secrétaire au Travail Tom Perez du Maryland , le représentant Tim Ryan de l’Ohio et la sénatrice Elizabeth Warren du Massachusetts . [110] Des rapports ultérieurs ont déclaré que Clinton envisageait également le secrétaire à l’Agriculture Tom Vilsack , l’amiral à la retraite James Stavridis et le gouverneur John Hickenlooper du Colorado. [111] En discutant de son choix potentiel de vice-président, Clinton a déclaré que l’attribut le plus important qu’elle recherchait était la capacité et l’expérience nécessaires pour entrer immédiatement dans le rôle de président.[111]

Le 22 juillet, Clinton a annoncé qu’elle avait choisi le sénateur Tim Kaine de Virginie comme colistier. [112] Les délégués à la Convention nationale démocrate de 2016 , qui a eu lieu du 25 au 28 juillet, ont officiellement nommé le ticket démocrate.

Petits partis et indépendants

Affiches de campagne des candidats tiers Jill Stein et Gary Johnson , octobre 2016 à St. Johnsbury, Vermont

Affiches de campagne des candidats tiers Jill Stein et Gary Johnson , octobre 2016 à St. Johnsbury, Vermont

Les candidats tiers et indépendants qui ont obtenu plus de 100 000 votes au niveau national ou au scrutin dans au moins 15 États sont répertoriés séparément.

Parti libertaire

- Gary Johnson , 29e gouverneur du Nouveau-Mexique . Candidat à la vice-présidence : Bill Weld , 68e gouverneur du Massachusetts

Approbations supplémentaires du parti : Parti de l’indépendance de New York

Accès au scrutin à tous les 538 votes électoraux

Nominés

Billet Parti Libertaire 2016 Billet Parti Libertaire 2016 |

|

|---|---|

| Gary Johnson | Soudure de facture |

| pour président | pour le vice-président |

|

|

| 29e gouverneur du Nouveau-Mexique (1995–2003) |

68e gouverneur du Massachusetts (1991–1997) |

| Campagne | |

|

Parti vert

- Jill Stein , médecin de Lexington, Massachusetts . Candidat à la vice-présidence : Ajamu Baraka , militant de Washington, DC

Accès au bulletin de vote pour 480 votes électoraux ( 522 avec écriture ) : [113] carte

- Sous forme écrite : Géorgie, Indiana, Caroline du Nord [114] [115]

- Procès d’accès au scrutin en cours: Oklahoma [116]

- Pas d’accès au scrutin : Nevada, Dakota du Sud [114] [117]

Nominés

Billet Parti Vert 2016 Billet Parti Vert 2016 |

|

|---|---|

| Jill Stein | Ajamu Baraka |

| pour président | pour le vice-président |

|

|

| Médecin de Lexington, Massachusetts |

Activiste de Washington, DC |

| Campagne | |

|

Parti constitutionnel

- Darrell Castle , avocat de Memphis, Tennessee . Candidat à la vice-présidence : Scott Bradley , homme d’affaires de l’Utah

Accès au bulletin de vote pour 207 votes électoraux ( 451 avec écriture ): [118] [119] carte

- Sous forme écrite : Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Géorgie, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginie [118] [120] [121] [122] [123]

- Pas d’accès au scrutin : Californie, District de Columbia, Massachusetts, Caroline du Nord, Oklahoma [118]

Nominés

| Billet du Parti de la Constitution 2016 | |

| Château de Darrell | Scott Bradley |

|---|---|

| pour président | pour le vice-président |

|

|

| Avocat de Memphis, Tennessee |

Homme d’ affaires de l’Utah |

| Campagne | |

| |

|

| [124] |

Indépendant

- Evan McMullin , directeur principal des politiques de la House Republican Conference . Candidat à la vice-présidence : Mindy Finn , présidente d’Empowered Women.

Approbation supplémentaire du parti : Parti de l’indépendance du Minnesota , Parti de l’indépendance de la Caroline du Sud

Accès au bulletin de vote pour 84 votes électoraux ( 451 avec écriture ) : [125] carte

- Sous forme écrite : Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Californie, Connecticut, Delaware, Géorgie, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Dakota du Nord, Ohio , Oregon, Pennsylvanie, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, Virginie-Occidentale, Wisconsin [125] [126] [127] [128] [129] [130] [131]

- Pas d’accès au scrutin : District de Columbia, Floride, Hawaï, Indiana, Mississippi, Nevada, Caroline du Nord, Oklahoma, Dakota du Sud, Wyoming

Dans certains États, le colistier d’Evan McMullin figurait sur le bulletin de vote sous le nom de Nathan Johnson plutôt que Mindy Finn, bien que Nathan Johnson ne soit censé être qu’un espace réservé jusqu’à ce qu’un véritable colistier soit choisi. [132]

| Billet Indépendant 2016 | |

| Evan McMullin | Mindy Finn |

|---|---|

| pour président | pour le vice-président |

|

|

| Directeur principal des politiques de la House Republican Conference (2015-2016) |

Présidente de Empowered Women (depuis 2015 ) |

| Campagne | |

|

|

| [133] |

Autres candidatures

Ces candidats ont obtenu au moins 0,01 % des suffrages (13 667 voix).

| Faire la fête | Candidat présidentiel | Candidat à la vice-présidence | Électeurs accessibles ( écrits ) |

Vote populaire | États avec accès au scrutin ( écrit ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parti pour le socialisme et la libération

Paix et Liberté [134] |

Gloria La Riva Imprimeur de journaux et activiste de Californie |

Eugene Puryear Activiste de Washington, DC |

112 ( 226 ) carte |

74 402 (0,05 %) |

Californie, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiane, New Jersey, Nouveau-Mexique, Vermont, Washington [136] [137] ( Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvanie, Rhode Island, West Virginie ) [127] [128] [130] [122] [138] [139] [140] [141] [142] |

| Indépendant | Richard Duncan Agent immobilier de l’Ohio |

Ricky Johnson Prédicateur de Pennsylvanie |

18 ( 173 ) |

24 307 (0,02 %) |

Ohio [143] ( Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Floride, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvanie, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginie-Occidentale ) [122] [138] [139] [144] [145] [140] [141] [137] [142] [146] [147] [148] [149] |

Campagne électorale générale

Un bulletin de vote pour les élections générales, énumérant les candidats à la présidentielle et à la vice-présidence

Un bulletin de vote pour les élections générales, énumérant les candidats à la présidentielle et à la vice-présidence

Croyances et politiques des candidats

Hillary Clinton a concentré sa candidature sur plusieurs thèmes, notamment l’augmentation des revenus de la classe moyenne, l’élargissement des droits des femmes, l’instauration d’une réforme du financement des campagnes et l’amélioration de la loi sur les soins abordables . En mars 2016, elle a présenté un plan économique détaillé fondant sa philosophie économique sur le capitalisme inclusif , qui proposait une «récupération» qui annule les réductions d’impôts et autres avantages pour les entreprises qui déplacent des emplois à l’étranger; avec des incitations pour les entreprises qui partagent les bénéfices avec les employés, les communautés et l’environnement, plutôt que de se concentrer sur les bénéfices à court terme pour augmenter la valeur des actions et récompenser les actionnaires ; ainsi que l’augmentation de la négociation collective droits; et imposer une “taxe de sortie” aux entreprises qui déplacent leur siège social hors des États-Unis afin de payer un taux d’imposition inférieur à l’étranger. [150] Clinton a promu un salaire égal pour un travail égal pour remédier aux prétendues insuffisances actuelles du montant que les femmes sont payées pour faire le même travail que les hommes, [151] a promu explicitement l’accent sur les questions familiales et le soutien à l’éducation préscolaire universelle , [152] a exprimé son soutien à le droit au mariage homosexuel , [152] et a proposé de permettreimmigrés sans papiers d’avoir un chemin vers la citoyenneté en déclarant qu’il “[i] est au cœur d’une question familiale”. [153]

La campagne de Donald Trump s’est fortement appuyée sur son image personnelle, renforcée par sa précédente exposition médiatique. [154] Le slogan principal de la campagne Trump, largement utilisé sur les produits de la campagne, était Make America Great Again . La casquette de baseball rouge avec le slogan inscrit sur le devant est devenue un symbole de la campagne et a été fréquemment enfilée par Trump et ses partisans. [155] Les positions populistes de droite de Trump – rapportées par le New Yorker comme étant nativistes , protectionnistes et semi- isolationnistes – diffèrent à bien des égards du conservatisme américain traditionnel . [156] Il s’est opposé à de nombreusesles accords de libre-échange et les politiques interventionnistes militaires que les conservateurs soutiennent généralement et se sont opposés aux réductions des prestations d’ assurance -maladie et de sécurité sociale . De plus, il a insisté sur le fait que Washington est “cassé” et ne peut être réparé que par un étranger. [157] [158] [159] Le soutien à Trump était élevé parmi les électeurs masculins blancs de la classe ouvrière et de la classe moyenne avec des revenus annuels inférieurs à 50 000 $ et aucun diplôme universitaire . [160] Ce groupe, particulièrement ceux qui n’ont pas de diplôme d’études secondaires , ont subi une baisse de leurs revenus au cours des dernières années. [161] Selon le Washington Post , le soutien à Trump est plus élevé dans les régions où le taux de mortalité des Blancs d’âge moyen est plus élevé. [162] Un échantillon d’entretiens avec plus de 11 000 répondants de tendance républicaine d’août à décembre 2015 a révélé que Trump à cette époque avait trouvé son plus fort soutien parmi les républicains de Virginie-Occidentale , suivi de New York . , puis de six États du Sud. [163]

Couverture médiatique

Clinton a eu une relation difficile – et parfois conflictuelle – avec la presse tout au long de sa vie dans la fonction publique. [164] Quelques semaines avant son entrée officielle en tant que candidate à la présidence, Clinton a assisté à un événement de la presse politique, s’engageant à repartir à zéro sur ce qu’elle a décrit comme une relation « compliquée » avec les journalistes politiques. [165] Clinton a d’abord été critiquée par la presse pour avoir évité de répondre à leurs questions, [166] [167] après quoi elle a accordé plus d’interviews.

En revanche, Trump a bénéficié des médias libres plus que tout autre candidat. Depuis le début de sa campagne jusqu’en février 2016, Trump a reçu près de 2 milliards de dollars d’attention médiatique gratuite, soit le double du montant que Clinton a reçu. [168] Selon les données du rapport Tyndall , qui suit le contenu des nouvelles nocturnes, jusqu’en février 2016, Trump représentait à lui seul plus d’un quart de toute la couverture électorale de 2016 dans les bulletins d’information du soir de NBC , CBS et ABC , plus que tous les démocrates. campagnes combinées. [169] [170] [171] Les observateurs ont noté la capacité de Trump à obtenir une couverture médiatique constante “presque à volonté”. [172] Cependant, Trump a fréquemment critiqué les médias pour avoir écrit ce qu’il prétendait être de fausses histoires à son sujet [173]et il a appelé ses partisans à être “la majorité silencieuse “. [174] Trump a également déclaré que les médias “mettaient un faux sens dans les mots que je dis”, et dit que cela ne le dérangeait pas d’être critiqué par les médias tant qu’ils étaient honnêtes à ce sujet. [175] [176]

Controverses

Clinton et Trump ont tous deux été mal perçus par le grand public, et leurs réputations controversées ont donné le ton de la campagne. [177]

Campagnes Trump à Phoenix, Arizona , 29 octobre 2016

Campagnes Trump à Phoenix, Arizona , 29 octobre 2016

La pratique de Clinton pendant son mandat de secrétaire d’État consistant à utiliser une adresse e-mail et un serveur privés , au lieu des serveurs du département d’État, a attiré l’attention du public en mars 2015. [178] Des inquiétudes ont été exprimées concernant la sécurité et la préservation des e-mails, et la possibilité que les lois peuvent avoir été violées. [179] Après que des allégations ont été soulevées selon lesquelles certains des e-mails en question appartenaient à cette catégorie dite « classée née », une enquête du FBI a été lancée concernant la manière dont les informations classifiées étaient traitées sur le serveur Clinton. [180] [181] [182] [183] L’enquête du FBI s’est terminée le 5 juillet 2016, avec une recommandation de non-accusation, une recommandation qui a été suivie par le ministère de la Justice.

Aussi, le 9 septembre 2016, Clinton a déclaré : « Vous savez, juste pour être grossièrement généraliste, vous pourriez mettre la moitié des partisans de Trump dans ce que j’appelle le panier des déplorables . Ils sont racistes, sexistes, homophobes, xénophobes, islamophobes… vous le nommez.” [184] Donald Trump a critiqué sa remarque comme insultant ses partisans. [185] [186] Le lendemain, Clinton a exprimé ses regrets d’avoir dit “la moitié”, tout en insistant sur le fait que Trump avait déplorablement amplifié “des opinions et des voix haineuses”. [187] Auparavant, le 25 août 2016, Clinton avait prononcé un discours critiquant la campagne de Trump pour avoir utilisé des “mensonges racistes” et permis à la droite alternative de gagner en importance. [188]

Campagnes de Clinton à Raleigh, Caroline du Nord , 22 octobre 2016

Campagnes de Clinton à Raleigh, Caroline du Nord , 22 octobre 2016

Le 11 septembre 2016, Clinton a quitté tôt un événement commémoratif du 11 septembre en raison d’une maladie. [189] Des séquences vidéo du départ de Clinton ont montré que Clinton devenait instable sur ses pieds et a été aidée à monter dans une camionnette. [190] Plus tard dans la soirée, Clinton a rassuré les journalistes sur le fait qu’elle “se sentait bien”. [191] Après avoir initialement déclaré que Clinton était devenue surchauffée lors de l’événement, sa campagne a ajouté plus tard qu’elle avait reçu un diagnostic de pneumonie deux jours plus tôt. [190] Les médias ont critiqué la campagne Clinton pour son manque de transparence concernant la maladie de Clinton. [190] Clinton a annulé un voyage prévu en Californie en raison de sa maladie. L’épisode a attiré l’attention du public sur des questions concernant la santé de Clinton. [191]

De l’autre côté, le 7 octobre 2016, une vidéo et l’audio d’accompagnement ont été publiés par le Washington Post dans lequel Trump faisait référence de manière obscène aux femmes dans une conversation de 2005 avec Billy Bush alors qu’elles se préparaient à filmer un épisode d’ Access Hollywood . Dans l’enregistrement, Trump a décrit ses tentatives d’initier une relation sexuelle avec une femme mariée et a ajouté que les femmes autoriseraient les célébrités masculines à tâtonner leurs organes génitaux (Trump a utilisé l’expression “attrapez-les par la chatte”). L’audio a suscité une réaction d’incrédulité et de dégoût de la part des médias. [192] [193] [194] Suite à la révélation, la campagne de Trump a publié des excuses, déclarant que la vidéo était d’une conversation privée d'”il y a de nombreuses années”.[195] L’incident a été condamné par de nombreux républicains éminents comme Reince Priebus , Mitt Romney , John Kasich , Jeb Bush [196] et le président de la Chambre Paul Ryan . [197] Beaucoup pensaient que la vidéo avait condamné les chances d’élection de Trump. Le 8 octobre, plusieurs dizaines de républicains avaient appelé Trump à se retirer de la campagne et à laisser Pence et Condoleezza Rice en tête. [198] Trump insister sur le fait qu’il n’abandonnerait jamais, mais s’étaient excusés pour ses remarques. [199] [200]

Donald Trump a également fait des déclarations fortes et controversées à l’égard des musulmans et de l’islam pendant la campagne électorale, en disant : “Je pense que l’islam nous déteste”. [201] Il a été critiqué et également soutenu pour sa déclaration lors d’un rassemblement déclarant : “Donald J. Trump appelle à un arrêt total et complet des musulmans entrant aux États-Unis jusqu’à ce que les représentants de notre pays puissent comprendre ce qui se passe.” [202] De plus, Trump a annoncé qu’il “examinerait” la surveillance des mosquées et a mentionné qu’il pourrait s’en prendre aux familles des terroristes nationaux à la suite de la fusillade de San Bernardino . [203]Sa forte rhétorique envers les musulmans a conduit les dirigeants des deux partis à condamner ses déclarations. Cependant, nombre de ses partisans ont partagé leur soutien à sa proposition d’interdiction de voyager , malgré le contrecoup. [202]

Tout au long de la campagne, Trump a indiqué dans des interviews, des discours et des publications sur Twitter qu’il refuserait de reconnaître le résultat de l’élection s’il était vaincu. [204] [205] Trump a faussement déclaré que l’élection serait truquée contre lui. [206] [207] Au cours du débat présidentiel final de 2016, Trump a refusé de dire au présentateur de Fox News Chris Wallace s’il accepterait ou non les résultats des élections. [208] Le rejet des résultats des élections par un candidat majeur aurait été sans précédent à l’époque car aucun candidat présidentiel majeur n’avait jamais refusé d’accepter le résultat d’une élection jusqu’à ce que Trump le fasse lui-même dans les années suivantes. Élection présidentielle de 2020 . [209] [210]

La controverse en cours sur l’élection a fait que des tiers ont attiré l’attention des électeurs. Le 3 mars 2016, le libertarien Gary Johnson s’est adressé à la Conférence d’action politique conservatrice à Washington, DC, se présentant comme l’option tierce pour les républicains anti-Trump. [211] [212] Début mai, certains commentateurs ont estimé que Johnson était suffisamment modéré pour éloigner les votes d’Hillary Clinton et de Donald Trump, qui étaient très détestés et polarisants. [213] Les médias conservateurs et libéraux ont noté que Johnson pourrait obtenir des votes des républicains “Never Trump” et des partisans mécontents de Bernie Sanders . [214]Johnson a également commencé à passer du temps à la télévision nationale, étant invité sur ABC News , NBC News , CBS News , CNN , Fox News , MSNBC , Bloomberg et de nombreux autres réseaux. [215] En septembre et octobre 2016, Johnson a subi « une série de faux pas dommageables lorsqu’il a répondu à des questions sur les affaires étrangères ». [216] [217] Le 8 septembre, Johnson, lorsqu’il est apparu sur MSNBC ‘s Morning Joe , a été interrogé par le panéliste Mike Barnicle , “Que feriez-vous, si vous étiez élu, à propos d’ Alep ?” (se référant à unville déchirée par la guerre en Syrie ). Johnson a répondu: “Et qu’est-ce qu’Alep?” [218] Sa réponse a suscité une large attention, en grande partie négative. [218] [219] Plus tard ce jour-là, Johnson a dit qu’il avait “blagué” et qu’il “comprenait la dynamique du conflit syrien – j’en parle tous les jours”. [219]

D’un autre côté, la candidate du Parti vert, Jill Stein , a déclaré que les partis démocrate et républicain sont “deux partis d’entreprise” qui ont convergé en un seul. [220] Préoccupée par la montée de l’ extrême droite à l’échelle internationale et la tendance au néolibéralisme au sein du Parti démocrate, elle a déclaré : « La réponse au néofascisme est d’arrêter le néolibéralisme. Mettre un autre Clinton à la Maison Blanche attisera les flammes de cette droite. extrémisme d’aile.” [221] [222]

En réponse au nombre croissant de sondages de Johnson, la campagne Clinton et les alliés démocrates ont intensifié leurs critiques à l’égard de Johnson en septembre 2016, avertissant qu'”un vote pour un tiers est un vote pour Donald Trump” et déployant le sénateur Bernie Sanders (l’ancien principal rival de Clinton, qui l’ont soutenue aux élections générales) pour convaincre les électeurs qui pourraient envisager de voter pour Johnson ou pour Stein. [223]

Le 28 octobre, onze jours avant les élections, le directeur du FBI, James Comey , a informé le Congrès que le FBI analysait des courriels supplémentaires de Clinton obtenus au cours de son enquête sur une affaire sans rapport . [224] [225] Le 6 novembre, il a informé le Congrès que les nouveaux courriels n’ont pas changé la conclusion antérieure du FBI. [226] [227]

Accès au scrutin

| Billet présidentiel | Faire la fête | Accès au scrutin | Voix [2] [228] | Pourcentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| États | Électeurs | % d’électeurs | ||||

| Atout / Pence | Républicain | 50 + CC | 538 | 100% | 62 984 828 | 46,09 % |

| Clinton / Kaine | Démocratique | 50 + CC | 538 | 100% | 65 853 514 | 48,18% |

| Johnson / Soudure | Libertaire | 50 + CC | 538 | 100% | 4 489 341 | 3,28 % |

| Stein / Baraka | Vert | 44 + CC | 480 | 89% | 1 457 218 | 1,07 % |

| McMullin / Finn | Indépendant | 11 | 84 | 15% | 731 991 | 0,54 % |

| Château / Bradley | Constitution | 24 | 207 | 39% | 203 090 | 0,15 % |

- Les candidats en gras figuraient sur des bulletins de vote représentant 270 votes électoraux, sans avoir besoin d’états écrits.

- Tous les autres candidats figuraient sur les bulletins de vote de moins de 25 États, mais avaient un accès écrit supérieur à 270.

Congrès du parti

![]()

![]() crême Philadelphia

crême Philadelphia ![]()

![]() Cleveland

Cleveland ![]() Orlando

Orlando ![]()

![]() Houston

Houston ![]()

![]() Salt Lake City class=notpageimage| Carte des lieux des congrès des partis pour les nominations aux candidatures présidentielles/vice-présidentielles. Parti démocrate parti républicain Parti libertaire Parti vert Parti constitutionnel parti républicain

Salt Lake City class=notpageimage| Carte des lieux des congrès des partis pour les nominations aux candidatures présidentielles/vice-présidentielles. Parti démocrate parti républicain Parti libertaire Parti vert Parti constitutionnel parti républicain

- Du 18 au 21 juillet 2016 : la Convention nationale républicaine s’est tenue à Cleveland , Ohio. [229] [230]

Parti démocrate

- Du 25 au 28 juillet 2016 : la Convention nationale démocrate s’est tenue à Philadelphie , en Pennsylvanie. [231]

Parti libertaire

- Du 26 au 30 mai 2016 : la Convention nationale libertaire s’est tenue à Orlando , en Floride. [232] [233]

Parti vert

- Du 4 au 7 août 2016 : la Convention nationale des Verts s’est tenue à Houston , au Texas. [234] [235]

Parti constitutionnel

- Du 13 au 16 avril 2016 : la convention nationale du Parti de la Constitution a eu lieu à Salt Lake City , dans l’Utah. [236]

Financement de la campagne

Wall Street a dépensé un montant record de 2 milliards de dollars pour tenter d’influencer l’élection présidentielle américaine de 2016. [237] [238]

Le tableau suivant est un aperçu de l’argent utilisé dans la campagne tel qu’il est signalé à la Commission électorale fédérale (FEC) et publié en septembre 2016. Les groupes extérieurs sont des comités indépendants de dépenses uniquement, également appelés PAC et SuperPAC . Les sources des nombres sont le FEC et OpenSecrets . [239] Certains totaux de dépenses ne sont pas disponibles, en raison de retraits avant la date limite du FEC. En septembre 2016 [update], dix candidats ayant accès au scrutin avaient déposé des rapports financiers auprès de la FEC.

| Candidat | Comité de campagne (au 9 décembre) | Groupes extérieurs (à partir du 9 décembre) | Total dépensé | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L’argent récolté | Argent dépensé | Encaisse | Dette | L’argent récolté | Argent dépensé | Encaisse | ||

| Donald Trump [240] [241] | 350 668 435 $ | 343 056 732 $ | 7 611 702 $ | 0 $ | 100 265 563 $ | 97 105 012 $ | 3 160 552 $ | 440 161 744 $ |

| Hillary Clinton [242] [243] | 585 699 061 $ | 585 580 576 $ | 323 317 $ | 182 $ | 206 122 160 $ | 205 144 296 $ | 977 864 $ | 790 724 872 $ |

| Gary Johnson [244] [245] | 12 193 984 $ | 12 463 110 $ | 6 299 $ | 0 $ | 1 386 971 $ | 1 314 095 $ | 75 976 $ | 13 777 205 $ |

| Rocky De La Fuente [246] | 8 075 959 $ | 8 074 913 $ | 1 046 $ | 8 058 834 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 8 074 913 $ |

| Jill Stein [247] [248] | 11 240 359 $ | 11 275 899 $ | 105 132 $ | 87 740 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 11 275 899 $ |

| Evan Mc Mullin [249] | 1 644 102 $ | 1 642 165 $ | 1 937 $ | 644 913 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 1 642 165 $ |

| Château de Darrell [250] | 72 264 $ | 68 063 $ | 4 200 $ | 4 902 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 68 063 $ |

| Gloria La Riva [251] | 31 408 $ | 32 611 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 32 611 $ |

| Monica Moorehead [252] | 14 313 $ | 15 355 $ | -$1,043 | -5 500 $ [A] | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 15 355 $ |

| Pierre Skewes [253] | 8 216 $ | 8 216 $ | 0 $ | 4 000 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 0 $ | 8 216 $ |

- ^ Dette due au comité

Droit de vote

L’élection présidentielle de 2016 était la première en 50 ans sans toutes les protections de la loi originale sur les droits de vote . [254] Quatorze États avaient mis en place de nouvelles restrictions de vote , y compris des États pivots tels que la Virginie et le Wisconsin. [255] [256] [257] [258] [259]

Approbations de journaux

Clinton a été approuvé par le New York Times , [260] le Los Angeles Times , [261] le Houston Chronicle , [262] le San Jose Mercury News , [263] le Chicago Sun-Times [264] et le New York Daily News [265] comités de rédaction. Plusieurs journaux qui ont approuvé Clinton, tels que le Houston Chronicle , [262] The Dallas Morning News , [266] The San Diego Union-Tribune , [267] The Columbus Dispatch [268] etLa République de l’Arizona [269] a approuvé son premier candidat démocrate depuis de nombreuses décennies. The Atlantic , qui est en circulation depuis 1857, a donné à Clinton sa troisième approbation (après Abraham Lincoln et Lyndon Johnson ). [270]

Trump, qui a fréquemment critiqué les médias grand public , n’a pas été approuvé par la grande majorité des journaux. [271] [272] Le Las Vegas Review-Journal , [273] Le Florida Times-Union , [274] et le tabloïd National Enquirer étaient ses partisans les plus en vue. [275] USA Today , qui n’avait approuvé aucun candidat depuis sa création en 1982, a rompu la tradition en donnant un anti-approbation contre Trump, le déclarant “inapte à la présidence”. [276] [277]

Gary Johnson a reçu des approbations de plusieurs grands quotidiens, dont le Chicago Tribune , [278] et le Richmond Times-Dispatch . [279] D’autres journaux traditionnellement républicains, y compris le New Hampshire Union Leader , qui avait approuvé le candidat républicain à chaque élection au cours des 100 dernières années, [280] et The Detroit News , qui n’avait pas approuvé un non-républicain au cours de ses 143 années , [281] a approuvé Gary Johnson.

Implication d’autres pays

Implication russe

Le 9 décembre 2016, la Central Intelligence Agency a rendu une évaluation aux législateurs du Sénat américain, déclarant qu’une entité russe avait piraté les e-mails du DNC et de John Podesta pour aider Donald Trump. Le Federal Bureau of Investigation a accepté. [282] Le président Barack Obama a ordonné un “examen complet” d’une telle intervention possible. [283] Début janvier 2017, le directeur du renseignement national, James R. Clapper , a témoigné devant une commission sénatoriale que l’ingérence de la Russie dans la campagne présidentielle de 2016 allait au-delà du piratage et incluait la désinformation et la diffusion de fausses nouvelles , souvent promues sur les réseaux sociaux. [284]Facebook a révélé que lors de l’élection présidentielle américaine de 2016, une société russe financée par Yevgeny Prigozhin , un homme d’affaires russe lié à Vladimir Poutine , [285] avait acheté des publicités sur le site Web pour 100 000 USD, [286] dont 25 % étaient géographiquement ciblée sur les États-Unis [287]

Le président élu Trump a initialement qualifié le rapport de fabriqué. [288] Julian Assange a déclaré que le gouvernement russe n’était pas la source des documents. [289] Quelques jours plus tard, Trump a déclaré qu’il pourrait être convaincu du piratage russe “s’il y a une présentation unifiée des preuves du Federal Bureau of Investigation et d’autres agences”. [290]

Plusieurs sénateurs américains, dont les républicains John McCain , Richard Burr et Lindsey Graham , ont exigé une enquête du Congrès. [291] La commission sénatoriale du renseignement a annoncé la portée de son enquête officielle le 13 décembre 2016, sur une base bipartite ; les travaux ont commencé le 24 janvier 2017. [292]

Une enquête officielle du conseil spécial dirigée par l’ancien directeur du FBI, Robert Mueller , a été ouverte en mai 2017 pour découvrir les opérations d’ingérence détaillées de la Russie et pour déterminer si des personnes associées à la campagne Trump étaient complices des efforts russes. Interrogé par Chuck Todd sur Meet the Press le 5 mars 2017, Clapper a déclaré que les enquêtes de renseignement sur l’ingérence russe menées par le FBI , la CIA , la NSA et son bureau ODNI n’avaient trouvé aucune preuve de collusion entre la campagne Trump et la Russie. [293]Mueller a conclu son enquête le 22 mars 2019 en soumettant son rapport au procureur général William Barr . [294]

Le 24 mars 2019, Barr a soumis une lettre décrivant les conclusions de Mueller, [295] [296] et le 18 avril 2019, une version expurgée du rapport Mueller a été rendue publique. Il a conclu que l’ingérence russe dans l’élection présidentielle de 2016 s’était produite “de manière radicale et systématique” et “avait violé le droit pénal américain”. [297] [298]

La première méthode détaillée dans le rapport final était l’utilisation de l’ Agence de recherche Internet , menant “une campagne sur les réseaux sociaux qui a favorisé le candidat présidentiel Donald J. Trump et la candidate présidentielle décriée Hillary Clinton”. [299] L’Internet Research Agency a également cherché à “provoquer et amplifier la discorde politique et sociale aux États-Unis”. [300]

La deuxième méthode d’ingérence russe a vu le service de renseignement russe, le GRU , pirater des comptes de messagerie appartenant à des volontaires et à des employés de la campagne présidentielle de Clinton, y compris celui du président de campagne John Podesta, et également pirater « les réseaux informatiques du Congrès démocrate ». Comité de campagne (DCCC) et le Comité national démocrate (DNC). » [301] En conséquence, le GRU a obtenu des centaines de milliers de documents piratés, et le GRU a procédé en organisant la diffusion de matériel piraté préjudiciable via l’organisation WikiLeaks ainsi que les personnalités du GRU ” DCLeaks ” et ” Guccifer 2.0 “. [302] [303]Pour établir si un crime a été commis par des membres de la campagne Trump au regard de l’ingérence russe, les enquêteurs du conseil spécial “ont appliqué le cadre du droit du complot “, et non la notion de “collusion”, car la collusion “n’est pas une infraction spécifique ou théorie de la responsabilité que l’on trouve dans le Code des États-Unis, et ce n’est pas non plus un terme technique du droit pénal fédéral. » [304] [305]Ils ont également enquêté sur la “coordination” des membres de la campagne Trump avec la Russie, en utilisant la définition de la “coordination” comme ayant “un accord – tacite ou exprès – entre la campagne Trump et le gouvernement russe sur l’ingérence électorale”. Les enquêteurs ont en outre expliqué que le simple fait d’avoir “deux parties prenant des mesures informées ou sensibles aux actions ou aux intérêts de l’autre” n’était pas suffisant pour établir la coordination. [306]

Le rapport Mueller écrit que l’enquête “a identifié de nombreux liens entre le gouvernement russe et la campagne Trump”, a révélé que la Russie “percevait qu’elle bénéficierait d’une présidence Trump” et que la campagne présidentielle Trump de 2016 “s’attendait à ce qu’elle bénéficie électoralement” de la Russie. efforts de piratage. En fin de compte, “l’enquête n’a pas établi que les membres de la campagne Trump avaient conspiré ou coordonné avec le gouvernement russe dans ses activités d’ingérence électorale”. [307] [308]

Cependant, les enquêteurs avaient une image incomplète de ce qui s’était réellement passé pendant la campagne de 2016, car certains associés de la campagne Trump avaient fourni des témoignages faux, incomplets ou refusés, ainsi que des communications supprimées, non enregistrées ou cryptées. En tant que tel, le rapport Mueller “ne peut exclure la possibilité” que des informations alors non disponibles pour les enquêteurs aient présenté des conclusions différentes. [309] [310] En mars 2020, le ministère américain de la Justice a abandonné ses poursuites contre deux entreprises russes liées à l’ingérence dans les élections de 2016. [311] [285]

Autres pays

Le Conseil spécial Robert Mueller a également enquêté sur les liens présumés de la campagne Trump avec l’ Arabie saoudite , les Émirats arabes unis , la Turquie , le Qatar , Israël et la Chine . [312] [313] Selon le Times of Israel , le confident de longue date de Trump, Roger Stone , “était en contact avec un ou plusieurs Israéliens apparemment bien connectés au plus fort de la campagne présidentielle américaine de 2016, dont l’un a averti Stone que Trump était ‘ va être vaincu à moins que nous n’intervenions” et a promis “nous avons des informations critiques”. ” [ 314] [315]

Le ministère de la Justice a accusé George Nader d’avoir fourni 3,5 millions de dollars en dons de campagne illicites à Hillary Clinton avant les élections et à Trump après avoir remporté les élections. Selon le New York Times , il s’agissait d’une tentative du gouvernement des Émirats arabes unis d’influencer l’élection. [316]

En décembre 2018, un tribunal ukrainien a jugé que les procureurs ukrainiens s’étaient mêlés des élections de 2016 en publiant des informations préjudiciables sur le président de la campagne Trump, Paul Manafort . [317]

Voice of America a rapporté en avril 2020 que « les agences de renseignement américaines ont conclu que les pirates chinois se sont mêlés aux élections de 2016 et de 2018 ». [318]

En juillet 2021, les procureurs fédéraux américains ont accusé l’ancien conseiller de Trump, Tom Barrack , d’être un agent de lobbying étranger non enregistré pour les Émirats arabes unis lors de la campagne présidentielle de 2016 de Donald Trump. [319] Un procureur général adjoint par intérim, Mark Lesko , avait déclaré que le ministère de la Justice était déterminé à mettre tout le monde « au courant », indépendamment de « leur richesse ou de leur pouvoir politique perçu ». Cependant, selon le HuffPost , l’ administration Bidena été vu poursuivre ses relations diplomatiques avec les Émirats arabes unis et que les Émirats arabes unis “se sont mieux comportés sous le président Joe Biden que ce à quoi on aurait pu s’attendre” compte tenu de l’accent mis par Biden et de ses critiques sur les mauvais dossiers en matière de droits de l’homme et les gouvernements qui se mêlent de la politique américaine. [320]

Expressions, phrases et déclarations notables

Par Trump et les républicains :

- “Parce que vous seriez en prison” : boutade improvisée de Donald Trump lors du deuxième débat présidentiel, en réponse à Clinton déclarant que c’était “affreusement bon quelqu’un avec le tempérament de Donald Trump n’est pas en charge de la loi dans notre pays .” [321]

- “Grande ligue” : un mot utilisé par Donald Trump notamment lors du premier débat présidentiel , mal entendu par beaucoup comme beaucoup , lorsqu’il a dit : “Je vais réduire les impôts de la grande ligue, et vous allez augmenter les impôts”. grande ligue.” [322] [323]

- « Construire le mur » : un chant utilisé lors de nombreux rassemblements électoraux de Trump, et la promesse correspondante de Donald Trump concernant le mur frontalier mexicain . [322]

- « Drain the swamp » : Une phrase que Donald Trump a invoquée en fin de campagne pour décrire ce qu’il faut faire pour régler les problèmes au sein du gouvernement fédéral. Trump a reconnu que la phrase lui avait été suggérée et il était initialement sceptique quant à son utilisation. [324]

- « Attrapez-les par la chatte » : une remarque faite par Trump lors d’une interview en coulisses de 2005 avec le présentateur Billy Bush sur Access Hollywood de NBCUniversal , qui a été publiée pendant la campagne. La remarque faisait partie d’une conversation dans laquelle Trump se vantait que “quand vous êtes une star, ils vous laissent faire”.

- “J’aime les gens qui n’ont pas été capturés” : la critique de Donald Trump à l’encontre du sénateur John McCain , qui a été détenu comme prisonnier de guerre par le Nord-Vietnam pendant la guerre du Vietnam . [325] [326]

- “Enfermez-la” : Un chant utilisé pour la première fois à la convention républicaine pour affirmer qu’Hillary Clinton est coupable d’un crime. Le chant a ensuite été utilisé lors de nombreux rassemblements de campagne de Trump et même contre d’autres politiciennes critiques de Trump, telles que la gouverneure du Michigan, Gretchen Whitmer . [327] [328]

- « Make America great again » : slogan de campagne de Donald Trump.

- « Le Mexique paiera » : la promesse de campagne de Trump selon laquelle s’il est élu, il construira un mur à la frontière entre les États-Unis et le Mexique , le projet étant financé par le Mexique. [329] [330]

- Surnoms utilisés par Trump pour ridiculiser ses adversaires : il s’agit notamment de “Crooked Hillary”, “Little Marco”, “Low-energy Jeb” et “Lyin’ Ted”.

- “La Russie, si vous écoutez” : Utilisé par Donald Trump pour inviter la Russie à “trouver les 30 000 mails qui manquent” (d’Hillary Clinton) lors d’une conférence de presse en juillet 2016 . [331]

- « Une femme si méchante » : la réponse de Donald Trump à Hillary Clinton après qu’elle ait déclaré que sa proposition d’augmentation des cotisations de sécurité sociale inclurait également les cotisations de sécurité sociale de Trump, « en supposant qu’il ne trouve pas comment s’en sortir ». [322] Plus tard réapproprié par les partisans de Clinton [332] [333] [334] et les féministes libérales . [335] [336] [337]

- “Ils apportent de la drogue. Ils apportent du crime. Ce sont des violeurs. Et certains, je suppose, sont de bonnes personnes” : la description controversée de Donald Trump de ceux qui traversent la frontière entre le Mexique et les États-Unis lors du lancement de sa campagne en juin 2015 . [338]

- « Qu’est-ce que tu as à perdre ? » : Dit par Donald Trump aux Afro-Américains du centre-ville lors de rassemblements à partir du 19 août 2016. [339] [340]

Par Clinton et les démocrates :

- « Panier de déplorables » : Une expression controversée inventée par Hillary Clinton pour décrire la moitié de ceux qui soutiennent Trump.

- “Je suis avec elle” : le slogan officieux de la campagne de Clinton (“Plus forts ensemble” était le slogan officiel). [341]

- “Quoi, comme avec un chiffon ou quelque chose?” : Dit par Hillary Clinton en réponse à la question de savoir si elle avait « effacé » ses e-mails lors d’une conférence de presse en août 2015. [325]

- “Pourquoi n’ai-je pas 50 points d’avance ?” : Question posée par Hillary Clinton lors d’une allocution vidéo à l’ Union internationale des travailleurs d’Amérique du Nord le 21 septembre 2016, qui a ensuite été transformée en publicité d’opposition par la campagne Trump. [342] [343]

- “Quand ils vont bas, nous allons haut” : a dit la première dame de l’époque, Michelle Obama , lors de son discours à la convention démocrate . [322] Cela a ensuite été inversé par Eric Holder . [344]

- “Feel the Bern” : Une phrase scandée par les partisans de la campagne de Bernie Sanders qui a été officiellement adoptée par sa campagne. [345]

Débats

Élection primaireÉlection générale

![]()

![]() Université Hofstra

Université Hofstra

Hempstead, NY ![]()

![]() Université de Longwood

Université de Longwood

Farmville, Virginie ![]()

![]() Université de Washington

Université de Washington

St. Louis, MO ![]()

![]() Université du Nevada

Université du Nevada

Las Vegas class=notpageimage| Sites des débats des élections générales de 2016

La Commission des débats présidentiels (CPD), une organisation à but non lucratif, a organisé des débats entre les candidats à la présidence et à la vice-présidence. Selon le site Web de la commission, pour pouvoir choisir de participer aux débats prévus, “en plus d’être constitutionnellement éligibles, les candidats doivent figurer sur un nombre suffisant de bulletins de vote d’État pour avoir une chance mathématique de remporter un vote majoritaire au Collège électoral. , et avoir un niveau de soutien d’au moins 15 % de l’électorat national, tel que déterminé par cinq organisations nationales de sondage d’opinion publique sélectionnées, en utilisant la moyenne des résultats les plus récemment publiés par ces organisations au moment de la détermination. » [346]

Les trois lieux ( Hofstra University , Washington University in St. Louis , University of Nevada, Las Vegas ) choisis pour accueillir les débats présidentiels, et le seul lieu ( Longwood University ) choisi pour accueillir le débat vice-présidentiel, ont été annoncés le 23 septembre. 2015. Le site du premier débat a été initialement désigné comme Wright State University à Dayton, Ohio ; cependant, en raison de la hausse des coûts et des problèmes de sécurité, le débat a été déplacé à l’Université Hofstra à Hempstead, New York . [347]

Le 19 août, Kellyanne Conway , la directrice de campagne de Trump a confirmé que Trump participerait à une série de trois débats. [348] [349] [350] [351] Trump s’était plaint que deux des débats programmés, l’un le 26 septembre et l’autre le 9 octobre, devraient concourir pour les téléspectateurs avec les matchs de la Ligue nationale de football , faisant référence aux plaintes similaires formulées concernant le des dates avec de faibles notes attendues lors des débats présidentiels du Parti démocrate . [352]

Il y a aussi eu des débats entre candidats indépendants.

| Non. | Date | Temps | Héberger | Ville | Modérateur(s) | Intervenants | Audience

(des millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 26 septembre 2016 | 21h00 HAE | Université Hofstra | Hempstead, New York | Lester Holt | Donald Trump Hillary Clinton |

84,0 [353] |

| vice-président | 4 octobre 2016 | 21h00 HAE | Université de Longwood | Farmville, Virginie | Elaine Quijano | Mike Pence Tim Kaine |

37,0 [353] |

| P2 | 9 octobre 2016 | 20h00 HAC | Université de Washington à Saint-Louis | Saint-Louis, Missouri | Anderson CooperMartha Raddatz |

Donald Trump Hillary Clinton |

66,5 [353] |

| P3 | 19 octobre 2016 | 18h00 HAP | Université du Nevada, Las Vegas | Las Vegas, Nevada | Chris Wallace | Donald Trump Hillary Clinton |

71,6 [353] |

Résultats

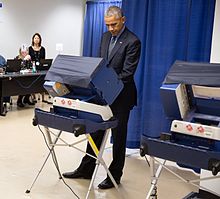

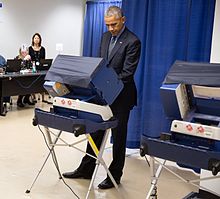

Le président Barack Obama vote tôt à Chicago le 7 octobre 2016

Le président Barack Obama vote tôt à Chicago le 7 octobre 2016

La nuit des élections et le lendemain

Les médias et les experts électoraux ont été surpris par la victoire de Trump au Collège électoral. À la veille du vote, la société de paris Spreadex avait Clinton dans un collège électoral réparti de 307 à 322 contre 216 à 231 pour Trump. [354] Les sondages finaux ont montré une avance de Clinton et à la fin, elle a reçu plus de votes. [355] Trump lui-même s’attendait, sur la base des sondages, à perdre les élections et a loué une petite salle de bal d’hôtel pour faire un bref discours de concession, remarquant plus tard : “J’ai dit que si nous perdons, je ne veux pas d’une grande salle de bal .” [356] Trump a étonnamment bien performé dans tous les États du champ de bataille , en particulier la Floride , l’Iowa , l’Ohio et en Caroline du Nord . MêmeLe Wisconsin , la Pennsylvanie et le Michigan , États qui devaient voter démocrate, ont été remportés par Trump. [357] Cindy Adams a rapporté que “Trumptown savait qu’ils avaient gagné à 5h30. Les mathématiques, les calculs, l’aversion des candidats provoquant l’abstention des électeurs ont engendré les chiffres.”[358]

Selon les auteurs de Shattered: Inside Hillary Clinton’s Doomed Campaign , la Maison Blanche avait conclu mardi soir que Trump gagnerait l’élection. Le directeur politique d’Obama, David Simas , a appelé le directeur de campagne de Clinton, Robby Mook , pour persuader Clinton de concéder l’élection, sans succès. Obama a ensuite appelé Clinton directement, invoquant l’importance de la continuité du gouvernement, pour lui demander de reconnaître publiquement que Trump avait gagné. [359] Estimant que Clinton ne voulait toujours pas concéder, le président a alors appelé son président de campagne John Podesta , mais l’appel à Clinton l’avait probablement déjà convaincue. [360]

Après que les réseaux eurent appelé la Pennsylvanie pour Trump, lui donnant 264 votes électoraux alors qu’il avait une avance de cinq points en Arizona, ce qui donne onze votes électoraux qui placeraient Trump au-dessus de la majorité de 270, Clinton s’est rendu compte qu’elle n’avait aucune chance de gagner l’élection et a appelé Trump tôt mercredi matin pour admettre sa défaite. [361] Clinton n’a pas pu faire de concession publique cette nuit-là, car elle n’avait écrit aucun discours de concession. [362]

Mercredi matin à 2 h 30, heure de l’Est (HE), il a été signalé que Trump avait obtenu les 10 votes électoraux du Wisconsin, lui donnant la majorité des 538 électeurs du Collège électoral , suffisamment pour faire de lui le président élu des États-Unis. États , [363] et à 2 h 50, Trump a prononcé son discours de victoire. [363]

Plus tard dans la journée, Clinton a demandé à ses partisans d’accepter le résultat et espérait que Trump serait “un président à succès pour tous les Américains”. [364] Dans son discours, Trump a appelé à l’unité, disant “il est temps pour nous de nous rassembler en un seul peuple uni”, et a félicité Clinton comme quelqu’un qui devait “une grande dette de gratitude pour son service à notre pays”. [365]

analyses statistiques

Six États plus une partie du Maine qu’Obama a remporté en 2012 sont passés à Trump (votes du Collège électoral entre parenthèses) : Floride (29), Pennsylvanie (20), Ohio (18), Michigan (16), Wisconsin (10), Iowa ( 6) et le deuxième district du Congrès du Maine (1). Initialement, Trump a remporté exactement 100 votes de plus au collège électoral que Mitt Romney en 2012, dont deux perdus contre des électeurs infidèles lors du décompte final. Trente-neuf États sont devenus plus républicains par rapport à la précédente élection présidentielle, tandis que onze États et le district de Columbia sont devenus plus démocrates. [228]

Sur la base des estimations du Bureau du recensement des États-Unis sur la population en âge de voter (VAP), le taux de participation des électeurs votant pour le président était supérieur de près de 1% à celui de 2012. Examinant le taux de participation global aux élections de 2016 , le professeur Michael McDonald de l’ Université de Floride a estimé que 138,8 millions d’Américains ont voté. En considérant une VAP de 250,6 millions de personnes et une population éligible au vote (VEP) de 230,6 millions de personnes, cela fait un taux de participation de 55,4% VAP et 60,2% VEP. [366] Sur la base de cette estimation, la participation électorale était en hausse par rapport à 2012 (54,1 % VAP) mais en baisse par rapport à 2008 (57,4 % VAP). Un rapport de la FEC sur l’élection a enregistré un total officiel de 136,7 millions de votes exprimés pour le président, soit plus que toute élection précédente. [1]Hillary Clinton a remporté 51,1% du vote bipartite et Donald Trump en a remporté 48,9%.

Le scientifique des données Hamdan Azhar a noté les paradoxes du résultat de 2016, affirmant que “le principal d’entre eux [était] l’écart entre le vote populaire, qu’Hillary Clinton a remporté par 2,8 millions de voix, et le collège électoral, où Trump a remporté 304-227”. Il a déclaré que Trump avait surpassé les résultats de Mitt Romney en 2012, tandis que Clinton n’avait égalé que les totaux de Barack Obama en 2012. Hamdan a également déclaré que Trump était “le plus grand gagnant de voix de tous les candidats républicains”, dépassant les 62,04 millions de voix de George W. Bush en 2004, bien qu’il n’ait pas atteint les 65,9 millions de Clinton, ni les 69,5 millions de voix d’Obama en 2008. Il a conclu, avec l’aide extrait du rapport politique Cook, que l’élection ne reposait pas sur la grande marge globale de 2,8 millions de votes de Clinton sur Trump, mais plutôt sur environ 78 000 votes de seulement trois comtés du Wisconsin, de la Pennsylvanie et du Michigan. [367]

Il s’agit de la première et de la seule élection depuis 1988 au cours de laquelle le candidat républicain a remporté les États du Michigan et de la Pennsylvanie, et la première depuis 1984 au cours de laquelle ils ont remporté le Wisconsin. C’était la première fois depuis 1988 que le républicain remportait le deuxième district du Congrès du Maine et la première fois depuis la victoire de George W. Bush dans le New Hampshire en 2000 qu’il remportait un État du Nord-Est.

L’élection de 2016 a marqué la huitième élection présidentielle consécutive où le candidat du grand parti victorieux n’a pas reçu une majorité de vote populaire par une marge à deux chiffres par rapport au(x) candidat(s) du grand parti perdant, la séquence des élections présidentielles de 1988 à 2016 dépassant la séquence de 1876 à 1900 pour devenir la plus longue séquence d’élections présidentielles de ce type dans l’histoire des États-Unis. [368] [note 1] [369]

Résultats électoraux

| Candidat à la présidentielle | Faire la fête | État d’origine | Vote populaire [2] | Vote électoral [2] | Partenaire de course | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compter | Pourcentage | Candidat à la vice-présidence | État d’origine | Vote électoral [2] | ||||

| Donald John Trump | Républicain | New York | 62 984 828 | 46,09 % | 304 (306) | Michel Richard Pence | Indiana | 304 |

| Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton | Démocratique | New York | 65 853 514 | 48,18% | 227 (232) | Timothée Michael Kaine | Virginie | 227 |

| Gary Earl Johnson | Libertaire | Nouveau Mexique | 4 489 341 | 3,28 % | 0 | William Floyd Weld | Massachusetts | 0 |

| Jill Ellen Stein | Vert | Massachusetts | 1 457 218 | 1,07 % | 0 | Ajamu Baraka | Illinois | 0 |

| D.Evan McMullin | Indépendant | Utah | 731 991 | 0,54 % | 0 | Mindy Finn | District de Colombie | 0 |

| Château de Darrell | Constitution | Tennessee | 203 090 | 0,15 % | 0 | Scott Bradley | Utah | 0 |

| Gloria La Riva | Socialisme et libération | Californie | 74 401 | 0,05 % | 0 | Eugène Puryear | District de Colombie | 0 |

| Billets ayant reçu des votes électoraux d’électeurs infidèles | ||||||||

| Bernie Sanders [b] | Indépendant | Vermont | 111 850 [c] | 0,08 % [c] | dix) | Élisabeth Warren [b] | Massachusetts | 1 |

| Jean Kasich [b] [d] | Républicain | Ohio | 2 684 [c] | 0,00 %[c] | dix) | Carly Fiorina [b] [d] | Virginie | 1 |

| Ron Paul [b] [d] | Libertaire [370] | Texas | 124 [c] | 0,00 % [c] | dix) | Michel Richard Pence | Indiana | 1 |

| Colin Powell [b] | Républicain | Virginie | 25 [c] | 0,00 % [c] | 3 (0) | Élisabeth Warren [b] | Massachusetts | 1 |

| Maria Cantwell [b] | Washington | 1 | ||||||

| Susan Collins [b] | Maine | 1 | ||||||

| Aigle tacheté de foi [b] | Démocratique | Dakota du Sud | 0 | 0,00 % | dix) | Winona LaDuke [b] | Minnesota | 1 |

| Autre | 760 210 | 0,56 % | — | Autre | — | |||

| Total | 136 669 276 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Nécessaire pour gagner | 270 | 270 |

Remarques:

- ^ a b Dans les décomptes État par État, Trump a gagné 306 électeurs promis, Clinton 232. Ils ont perdu respectivement deux et cinq voix face à des électeurs infidèles . Les candidats à la vice-présidence Pence et Kaine ont respectivement perdu une et cinq voix. Trois autres votes d’électeurs ont été invalidés et refondus.

- ^ un bcd e f g h i j k A reçu un ou plusieurs votes électoraux d’un électeur infidèle

- ^ un bc _ Le a reçu des votes par écrit. Le nombre exact de votes écrits a été publié pour trois États : la Californie, le Vermont et le New Hampshire. [371]Il était possible de voter Sanders comme candidat écrit dans 14 États. [ citation nécessaire ]

- ^ un bc Deux électeurs infidèles du Texas ont voté respectivement pour Ron Paul et John Kasich. Chris Suprun a déclaré qu’il avait voté pour John Kasich à la présidence et pour Carly Fiorina à la vice-présidence. L’autre électeur infidèle du Texas, Bill Greene, a voté pour Ron Paul à la présidence, mais a voté à la vice-présidence pour Mike Pence, comme promis. John Kasich a reçu des votes écrits enregistrés en Alabama , Géorgie , Illinois , New Hampshire , Caroline du Nord , Pennsylvanie et Vermont .

|

|||||||||||||||

| 232 | 306 | ||||||||||||||

| Clinton | Atout | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Résultats par état

Le tableau ci-dessous affiche les décomptes officiels des votes selon la méthode de vote du collège électoral de chaque État. La source des résultats de tous les États est le rapport officiel de la Commission électorale fédérale. [2] La colonne intitulée “Marge” montre la marge de victoire de Trump sur Clinton (la marge est négative pour chaque État que Clinton a gagné).

Au total, 29 candidats tiers et candidats indépendants à la présidence se sont présentés sur le bulletin de vote dans au moins un État. L’ancien gouverneur du Nouveau-Mexique Gary Johnson et le médecin Jill Stein ont répété leurs rôles de 2012 en tant que candidats pour le Parti libertaire et le Parti vert , respectivement. [372] Avec un accès au scrutin à l’ensemble de l’électorat national, Johnson a reçu près de 4,5 millions de voix (3,27 %), la part de voix la plus élevée à l’échelle nationale pour un candidat tiers depuis Ross Perot en 1996 , [373] tandis que Stein a reçu près de 1,45 million de voix (1,06 % ), le plus pour un candidat vert depuis Ralph Nader en 2000 .

Le candidat indépendant Evan McMullin , qui figurait sur le bulletin de vote dans 11 États, a obtenu plus de 732 000 voix (0,53 %). Il a remporté 21,4 % des voix dans son État d’origine, l’Utah, la part la plus élevée des voix pour un candidat tiers dans tous les États depuis 1992. [374] Malgré son abandon des élections suite à sa défaite à la primaire démocrate, le sénateur Bernie Sanders a obtenu 5,7% des voix dans son État d’origine, le Vermont, le pourcentage de campagne de brouillon écrit le plus élevé pour un candidat à la présidentielle de l’histoire américaine. [375]Johnson et McMullin ont été les premiers candidats tiers depuis Nader à obtenir au moins 5% des voix dans un ou plusieurs États, Johnson franchissant la barre dans 11 États et McMullin la franchissant dans deux.